George Washington and various of his generals had their doubts about the effectiveness of volunteer militia units as the Revolutionary War intensified. The solution was to create a regular army of “Continental” units. These were to be made up of men willing to commit to serve for the long term, and led by experienced officers approved by both Congress and the commander-in-chief. Washington intended to manage the Continental forces in a standard top-down military hierarchy, supplementing them with militia regiments raised at the state or local levels.

Some members of Congress objected to the establishment of a regular Continental Army. They believed that a well-regulated militia was both necessary and sufficient for the security of a free state. But the majority concluded that militia units, while necessary, were insufficient, and their conclusion prevailed. As the war continued, most generals came to prefer Continental regiments over militia regiments, believing the Continentals to be better trained, better equipped, more experienced, more committed, more easily deployed, and thus more reliable in action.

Washington initially thought that mounted militia units were particularly unappealing. That was because in addition to being unreliably manned by short-termers, they had livestock, fodder, and equipment requirements that made them expensive to maintain. He changed his mind after the 1776 campaign around New York City, where Connecticut Light Horse militia troops performed valuable service.[1] The romantic image of mounted combat and heroic charges was already becoming obsolete, but dragoons proved to be very useful for reconnaissance, communication, guarding mounted officers, and escorting prisoners.

Two light horse cavalry troops from Connecticut, one Continental and the other state militia, later served together at Saratoga in the autumn of 1777. They were the Continentals of Vernejoux’s 2nd Troop from Sheldon’s 2nd Dragoons, and Hyde’s detachment from the 4th Connecticut Light Horse Militia. Comparison of the organization and performance of these two troops in 1777 provides an informative case study.

The Connecticut Light Horse Militia

Militias arose in Connecticut and other British colonies in American as emergent, self-organizing, bottom-up, organizations. Local militia companies were personalized, known by the names of their commanders. For example, Connecticut infantry militia regiments that fought at Saratoga were known as Latimer’s Regiment and Cook’s Regiment.

There were the thirteen Connecticut militia regiments in 1767. By 1774, the year before the Revolutionary War broke out, the list had grown to twenty-two regiments. By 1776 Connecticut had twenty-eight regiments. The Connecticut legislature realized that the exigencies of warfare required them to impose some additional regulatory measures on their militia regiments. They were accordingly all assigned top down to one or another of six new militia brigades, each under the command of a brigadier general appointed by the state. This evolution is laid out in an excellent article by John Robertson.[2]

Initially, most Connecticut militia regiments had some mounted men, depending upon which of them happened to have suitable horses. By May/June 1776, the legislature decided to detach the mounted troopers from their regiments and created five new light horse militia regiments, each with up to six troops (sometimes referred to as companies). The regimenting of the mounted troops did not map to the brigading of their source regiments. While there were six new infantry brigades, there were new five new light horse regiments, drawn from differently defined districts of Connecticut.[3]

Each Connecticut Light Horse regiment was to be commanded by a major. By numbering the regiments, the legislature created a structure that could evolve to be uncoupled from the personal identities of unit commanders. This was a top-down process like Washington’s organization of the Continental Army.

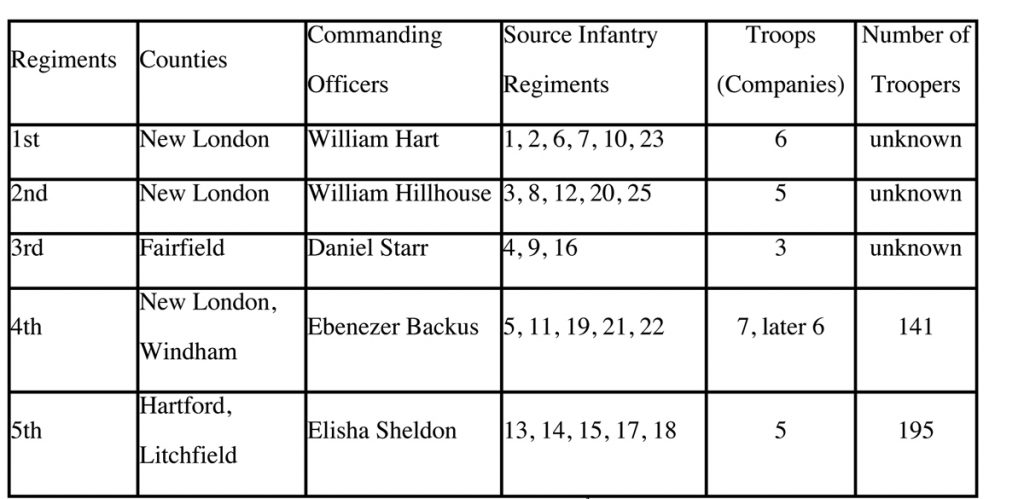

Each new light horse regiment was authorized to have up to six troops and a total of 200 officers and troopers. Thus, each of five troops (companies) of a light horse regiment was authorized to have up to a total of forty officers and men. True strengths were always below that. In July 1776, Maj. Ebenezer Backus’s 4th regiment had only 141 rank and file while Elisha Sheldon’s 5th regiment had 195 (Table 1).

Table 1. Connecticut Light Horse regiments in July 1776.[4]

Table 1. Connecticut Light Horse regiments in July 1776.[4]

Sheldon’s 2nd Continental Light Dragoon Regiment

Elisha Sheldon’s 1776 5th militia regiment was drawn from older militia regiments in northwestern Connecticut. They served well in the siege of Boston and Sheldon proposed that the 5th Connecticut Light Horse be federalized. Washington initially declined the offer. In 1776 Sheldon took the 5th Connecticut Light Horse to New York, where they provided important support for Washington’s army there and in New Jersey. By November 3, 1776 Sheldon had seven troops of dragoons in his regiment, each commanded by a captain, or in one case by a lieutenant.[5]

Washington sent Sheldon back to Connecticut in December 1776, with orders to raise a Continental dragoon regiment.[6] Washington also invited three other men to organize regiments for a new Continental Corps of Light Dragoons. The corps consisted of four regiments, each authorized to raise six troops and 280 men:[7]

1st Light Dragoons: formerly Theodoric Bland’s Virginia Horse.

2nd Light Dragoons: formerly Elisha Sheldon’s Connecticut 5th Light Horse.

3rd Light Dragoons: formerly George Baylor’s Virginia Horse.

4th Light Dragoons: formerly Stephen Moylan’s Pennsylvania Horse.

Elisha Sheldon’s 5th Connecticut Light Horse militia regiment was thus replaced by the Continental 2nd Regiment of Dragoons. Sheldon was promoted to colonel as part of this transition.[8] By January 1777 Sheldon had formed the authorized six troops, all commanded by captains:

1st Troop: Capt. Benjamin Tallmadge.

2nd Troop: Capt. Jean Louis de Vernejoux.

3rd Troop: Capt. Josiah Stoddard.

4th Troop: Capt. Epaphras Bull.

5th Troop: Captain William Barnett.

6th Troop: Captain Nathaniel Crafts.

Two captains came from other states, Barnett from New Jersey and Crafts from Massachusetts. Sheldon also acquired the services of a French volunteer captain, Jean Louis de Vernejoux. Thus, it was not just a simple matter of converting an established militia regiment to a new Continental one. The 1776 militia regiments had disbanded with the onset of winter. Sheldon and other officers of the new Continental units were charged with recruiting anew. There was much uncertainty, and preparations bogged down. Worse, there were too few horses and not enough equipment to even begin to train a full regiment.[9]

Sheldon and his captains recruited Continental troopers from across Connecticut, with only a few, if any, coming from the northwestern 5th militia light horse regiment he had previously commanded. Indeed, only a few came from any of the Connecticut militia dragoon regiments of 1776. For example, the bulk of those recruited into the new 2nd troop commanded by Vernejoux came from in and around Hartford and Lebanon, but they did not include more than a few former militiamen.

Benjamin Tallmadge was commissioned captain of 1st Troop by John Hancock on December 14, 1776. The entire regiment was then gathered at Wethersfield, Connecticut for organization and initial preparations for the 1777 campaign. Tallmadge’s troopers were all mounted on dapple gray horses.[10] Tallmadge’s command of 1st Troop did not last long, for he was promoted to major on April 7, 1777 and he took up new duties as a senior staff officer under Colonel Sheldon.

As with other Continental units, the organization of Sheldon’s regiment of dragoons was in constant flux due to deaths, discharges, enlistments, and promotions. Unlike militia units, Continental units had the standard practices of regular armies for managing the appointments and promotions of officers.

The 2nd Troop of the 2nd Regiment, commanded by Captain Vernejoux, was the Continental dragoon troop that would later serve under Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates in the Northern Army at Saratoga. In June 1777, Sheldon sent Vernejoux’s troop to join the Northern Army, then still under the command of Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler. The troop went first to the Schoharie Valley to help suppress Loyalists west of Albany and to provide Albany militia units with cavalry support to keep them engaged and effective. The 2nd Troop was known as the “Blacks,” then and later during the Saratoga campaign, because of the dark color of all their horses; recall that the horses of the 1st Troop were all grays. It appears that men were recruited into at least two Continental Dragoon troops based in part on the colors of their horses.[11]

The military disaster at Fort Ticonderoga caused Congress to replace Philip Schuyler with Horatio Gates. By August 1777 Gates was in command of the Northern Army and Vernejoux’s troop was still engaged in the Schoharie Valley. Late that month Lt. Thomas Seymour sent Gates a letter explaining the current status of the 2nd Troop.

Lieutenant Seymour reported that only six officers and fourteen privates were present and fit for duty on August 27. Seymour’s letter indicates a total strength of thirty-one officers and men at that time. He explained that Vernejoux was sick in the Albany hospital. Two sergeants were absent on command with two enlisted men. Another enlisted man was on express and had not yet returned. A fifth corporal and four additional troopers were on their way and expected to join the 2nd Troop soon.

Two unidentified men had deserted. Amos Hull, William Wooding, and Jonathan McKinsey were all listed as having deserted sometime between their enlistments and the autumn of 1778.[12] Thus, one of the three must have been at Saratoga, but it is currently not possible to say which of them it was. The troop’s farrier, Daniel Davis, was not mentioned by Seymour, possibly because he regarded Davis as a noncombatant civilian employee.

One other trooper, Samuel Crocker, had been killed at Schoharie on the 1st of June, the first death experienced by the 2nd Troop. Three other men had been wounded and were with Vernejoux in the Albany hospital. For the remaining thirty officers and men there were only fifteen horses fit for duty.

A running roster kept by Benjamin Tallmadge after his promotion to major and second in command of the 2nd Regiment of Dragoons allows reconstruction of the 2nd Troop roster at Saratoga. Seventy-eight officers and enlisted men in Tallmadge’s roster book are listed, more or less in the chronological order in which they had joined the 2nd Troop. Of those seventy-eight, forty enlisted too late to have been part of the 2nd Troop at Saratoga. Setting aside the one killed at Schoharie, thirty-eight (eleven officers and twenty-six privates) probably served at Saratoga.[13]

The 2nd Troop officers who must have served at Saratoga were:

Capt. Jean Louis de Vernejoux, deserted October 15, 1777.

Lt. Thomas Young Seymour, promoted to captain October 20, 1777.

Cornet Thomas Burkmar, promoted to captain October 20, 1777.

Qtr. Mr. Sgt. Hezekiah Whitmore.

Drill Sgt. Nathaniel Brewster.

Cpl. Andrew Bostwick.

Cpl. Jacques Rosard.

Cpl. Gideon Hanley (later promoted to quartermaster sergeant).

Cpl. Wilson Franklin.

Cpl. Charles West.

Farrier Daniel Davis.

Trumpeter Asuel Gilbert (probably replaced John Conley in May 1777).

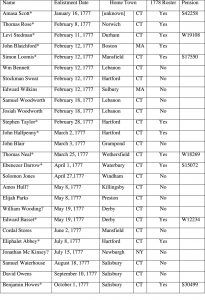

Table 2 shows all twenty-six names taken from Tallmadge’s list of recruits, excluding the man killed earlier at Schoharie. The twelve still on Thomas Seymour’s 1778 roster a year after Saratoga are identified by an asterisk. These twelve privates were all men who certainly served at Saratoga because their enlistment dates preceded the battles there and they were still in the troop in 1778. Twelve others were probably but less certainly present. Recall that Seymour had reported that he had only twenty-one privates present or soon to be present in August 1777. As noted earlier, three of the men listed ultimately deserted, but one of the three was probably still present at Saratoga. These three are identified by question marks.

Table 2. Twenty-three privates who probably (*certainly) served in the 2nd Dragoons at Saratoga, and three that are questionable. Seven of the names are also confirmed in pension records.

Table 2. Twenty-three privates who probably (*certainly) served in the 2nd Dragoons at Saratoga, and three that are questionable. Seven of the names are also confirmed in pension records.

Following Burgoyne’s defeat, Captain Seymour escorted British officers to internment in Boston. There Burgoyne presented Seymour with a leopard skin saddle cloth, which Seymour subsequently used in formal events.[14] An important observation to take away from all of this is that even a Continental dragoon regiment experienced constant turnover in personnel. Casualties, recruitment, transfers, promotions, desertions, and repeated army reorganizations account for it. Another important observation is that the 2nd Troop had a total of only about thirty-six officers and men at Saratoga.

Hyde’s Regiment of Connecticut Light Horse Militia

The State of Connecticut detached mounted troopers from all existing militia regiments in May 1776, forming them into five light horse regiments as described earlier. This turned all twenty-five source regiments into exclusively infantry regiments. The new dragoon militia regiments were established by July 1777.

Ebenezer Backus was commander of the new 4th Light Horse, about which several details are known (Table 1). The new 4th drew troopers from six older militia regiments in northeastern Connecticut. Only a few of those troopers were later recruited into Sheldon’s 2nd Dragoon regiment. Backus initially had officers and men in seven troops in his regiment:

1st Troop: Capt. James Green.

2nd Troop: Capt. Isaac Sergeant.

3rd Troop: Capt. Amasa Keyes.

4th Troop: Capt. Joel Loomis.

5th Troop: Capt. Samuel Hall.

6th Troop: Capt. Elijah Hyde.

7th Troop: Capt. Andrew Lathrop.

On September 7, 1776 Backus had a total of 160 men in the seven troops. By October 4, he had 158. On October 26, he had 146. Leaving aside the severely undermanned 7th Troop, there were an average of only twenty-five officers and men in each shrinking troop. There were only twenty unnamed rank and file troopers in Hall’s troop at that time, and Hyde had twenty-nine. While Hall’s troop had five officers, Hyde’s had nine. Other troops had as many as thirty-one men or as few as eight. The small number (eight) in Lothrop’s 7th Troop led to its elimination, which brought the regiment to the legal maximum of six allowed.[15] The upshot is that in 1776 a typical Connecticut Light Horse troop had only about twenty-five officers and men. Official rosters are lacking, but there is no reason to believe that these numbers were substantially higher in 1777, particularly as there was a very high turnover rate in militia units from one year to the next.

The militia troopers enlisted for 1776 had committed for only a few months service that year, and many left their units over the winter. None of the twenty-one troopers listed by Hall in December 1776, or the twenty-seven listed by Hyde, joined Sheldon’s new 2nd Dragoon regiment during the winter or later.[16] How many reenlisted as Light Horse militiamen is unknown. Whatever their numbers, it is unlikely that either troop had more than about two dozen rank and file during 1777.

Major Backus detached men from Elijah Hyde’s and Samuel Hall’s troops and sent them to serve together under Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates at Saratoga. The detached men were combined into a single troop for that deployment, and Captain Hyde was promoted to major so he could command the combined detachments.[17] Hall’s Lt. John Stewart went along to serve under Hyde.

Nathaniel Barnett joined Hall’s troop in 1777. Barnett’s pension petition is particularly important because it clarifies the ad hoc composition of the Connecticut Light Horse militia unit that served at Saratoga.[18] It indicates that about half the men from each of the two troops rode north, along with a few volunteers from two other of Backus’s troops. They appear to have not traveled together as a unit. Hyde and his detached troopers found each other and rode into the Northern Army camp on September 1, 1777.

Major Hyde’s ad hoc militia troop probably numbered fewer than ten officers and thirty men. A partial list of the officers and men can be compiled from information taken from individual pension petitions filed after the war. The officers and enlisted troopers known to have served at Saratoga are:

Maj. Elijah Hyde’s Detachment.

Lt. Abraham Fitch (Hyde’s troop; Dewey’s petition S. 17,926).

Lt. John Stewart (Hall’s troop; Barnett’s petition R. 536).

Cornet Eliphalet Bingham (Green’s troop; Fox’s petition R. 3732).

(Quartermaster Amos Thomas?).

Cpl. Ebenezer Eaton (Hall’s troop; petition W. 21,038).

(Clerk Elijah Metcalf?).

Trumpeter John Roberts (Butler’s Troop; petition S. 11,329).

Gilbert Garey (Hyde’s Troop; petition R. 3961).

Denison Wattles (Hyde’s Troop; William Morgan petition W. 1308).

George Dorrance (Hall’s Troop; Barnett’s petition R. 536).

Asa Shepard (Hall’s Troop; petition S. 14,435).

Ebenezer Spaulding (Hyde’s Troop; Eaton petition W. 21,038).

Isaiah Loomis (Green’s Troop; petition W. 8054).

Israel Morgan (Keyes’s Troop; William A. Morgan petition W. 1308).

Nathaniel Barnett (Hall’s Troop; petition R. 536).

Jesse Fox (Green’s Troop, petition R. 3732).

Jacob Loomis (Hall’s Troop; Fox’s petition R. 3732).

Squire Cady (Hall’s Troop; petition W. 1553).

Daniel Dewey (Green’s Troop; petition S. 17,926).

Charles Wattles (Green’s Troop; petition S. 14,799).[19]

Cavalry at Saratoga, 1777

Borden Mills, and perhaps other earlier historians, wrote that “the cavalry at Saratoga in 1777 consisted of a small detachment of 150 Connecticut Light Horse, under Lieutenant Colonel Elijah Hyde.”[20] It is not certain whether he was referring to just Hyde’s Light Horse detachment or to Vernejoux’s Continental troop as well. In either case he vastly overstated their numbers. The official maximum strength of a militia cavalry regiment was set unrealistically at 200. Troops actually averaged a maximum of about thirty-three. Various sources appear to have confused authorized regimental and troop strengths, and they consequently suggested high numbers at Saratoga.[21]

Brig. Gen. John Glover reported on September 5, 1777 that Hyde and his regiment had arrived at Bemis Heights with 200 officers and men.[22] This too was an exaggeration, based on authorized rather than actual strength of an entire regiment rather than a unit consisting of only two troop detachments. Hyde had told Glover that more men from two regiments of infantry militia were also on the way. They had begun arriving on September 1.[23] By September 6 there were a “considerable body” of Connecticut infantry as well as light horse in camp on Bemis Heights.[24]

There was occasional conflict between the Continental and militia units. This prompted General Glover to issue a new standing order on September 13, designed to put an end to it in his brigade. Glover’s standing order was specifically intended to quell disputes between Massachusetts Continentals and Albany infantry militiamen.[25] The cavalry units were under Gates’s direct command, not in Glover’s brigade, but the same kinds of conflicts could have existed between the Continental dragoons and the Connecticut light horse militiamen.

Hyde’s Saratoga Dragoon Regiment

Hyde had only thirty-six officers and men in Vernejoux’s 2nd Troop, and the approximately ten officers and thirty men detached from four troops of Backus’s 4th Connecticut Light Horse. Nearly all of the men in both units were from Connecticut. This and their small numbers probably made for relatively few conflicts. However, there likely was a serious conflict in Hyde’s very small Light Horse regiment, between Major Hyde himself and Capt. Jean Louis de Vernejoux. It probably rankled Vernejoux to be subordinated to a militiaman who had only recently been promoted to the rank of major. Vernejoux remained in command of his troop until October 15, 1777, after the two major battles but before the surrender of Burgoyne at Saratoga. Gates reported that Vernejoux “ran away” on that day, leaving the commander to find a replacement.[26]

Thomas Seymour had been promoted and commissioned as a lieutenant since January 10, 1777. Gates promoted him to captain and gave him command of the 2nd Troop on October 20, 1777, five days after Vernejoux left. Seymour served in that capacity until his resignation on November 23, 1778.

On October 16, 1777, his army surrounded by growing American forces, Burgoyne demanded that Gates provide him with an accurate return regarding the strength of the Northern Army.[27] Gates responded quickly, apparently based on his own estimates and those of his brigadiers rather than by compiling accurate returns from the smaller units under his command. Gates’s bottom line was that he had 13,216 officers and men under his command surrounding Burgoyne’s forces. Gates claimed to have 25 officers and 346 men (321 present and fit for duty) in eight cavalry companies (troops) at Saratoga on October 16, 1777.[28] That very large number amounted to an average about forty-three officers and men per troop, perhaps a believable number if he truly had eight troops. But Gates officially had only two troops, under the command of a militia major.

In 1951, Charles Snell estimated that Gates had 200 Connecticut Light Horsemen on the 19th of September. He based this on three sources.[29] The numbers provided by two of these sources were exaggerated guesses based on authorized regimental numbers. None of them conform with the evidence above, which shows that the 200 cavalry Snell estimated were available to Major Hyde by September 19, 1777 cannot be correct. Elsewhere Snell estimated that Hyde still had that many cavalry on October 7, qualifing it by stating that their “figures are for total strength, not effective strength.”[30]

Gates’s report to Burgoyne claimed a total of 371 (25 + 346) cavalry officers and troopers, and Snell might have allowed that exaggerated number to inflate his own estimates. A careful reconstruction of the October 7, 1777 order of battle accounts for only one major, one captain, and two small troops of cavalry.[31] The combined number of officers and enlisted cavalrymen could not have exceeded eighty. Perhaps six additional troops of mounted men arrived with the flood of Albany infantry militia regiments that came to Bemis Heights in the days preceding and following the battle of October 7,[32] but there is no evidence to support that possibility. It seems more likely that Horatio Gates simply inflated his numbers in order to intimidate Burgoyne into submission.

Conclusions

Cavalry units were expensive to form and maintain. Continental units could expect some clothing, equipment, and supplies from the government, but there were persistent shortages. Troopers typically provided their own mounts, in both Continental and militia units. Horses each required twenty pounds of forage daily, and were often debilitated by hard service. About half the horses of Vernejoux’s troop of the 2nd Dragoons were unfit for duty after the Schoharie campaign, leaving too few to provide fit mounts for half the men as the troop joined the Northern Army in September 1777.

Unless many more letters and diaries written by men who joined the flood of volunteers from in and around Albany to Bemis Heights surface, historians may never sort out the details of the chaotic climax at Saratoga. In some ways it was a replay of Boston two years earlier, when Burgoyne dismissed the Americans as “a rabble in arms, flushed with success and insolence” in a letter to Lord Rochfort.

The troop from Sheldon’s 2nd Dragoons performed well at Schoharie and later at Saratoga. So did Hyde’s ad hoc troop of men from Backus’s Connecticut Light Horse militia. The critical difference between the Continental troopers and the militia troopers was not their relative effectiveness in action. The difference was at the level of logistics and tactics. Washington could count on the prompt availability of standing Continental units, and their rapid deployment through his top-down command and control. State militia units were logistically less dependable. As was the case for infantry militia units, cavalry militia units were too dependent upon ad hocarrangements. However, once engaged they performed well. This was a view ruefully shared by Burgoyne in defeat: “The standing corps which I have seen are disciplined. I do not hazard the term, but apply it to the great fundamental points of military institution, sobriety, subordination, regularity, and courage. The militia are inferior in method and movement, but not a jot less serviceable in woods.”[33]

Acknowledgments

I thank Erin Weinman of the New-York Historical Society for providing me with a copy of Lieutenant Seymour’s August 27, 1777 letter to Gates. I also thank Diane Vantuno for her transcription of Nathaniel Barnett’s pension petition and related documents.

[1]In modern usage “troop” often means “soldier.” Troop is used here as a collection of mounted soldiers.

[2]John Robertson, “Decoding Connecticut Militia 1739-1783,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 27, 2016.

[3]Charles Hoadly, ed., The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut (Hartford: Case, Lockwood and Brainard, 1890), 15:284-285.

[4]Robertson, “Decoding Connecticut Militia.”

[5]“A Return of Seven Companies of Light Horse from the State of Connecticut under the comand of Major Sheldon,”Revolutionary War Rolls, National Archives and Records Administration.

[6]John Hayes, Connecticut’s Revolutionary Cavalry, Sheldon’s Horse (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1975), 9.

[7]“Size Roll of the 2nd Regiment of Dragoons,” Revolutionary War Rolls. Francis Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution: April, 1775 to December, 1783 (Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop, 1914).

[8]Heitman, Historical Register.

[9]Hayes, Connecticut’s Revolutionary Cavalry, 9-10.

[10]Benjamin Tallmadge, Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge (New York: Thomas Holman, 1858), 17-19.

[11]Gavin Watt, “Continental Dragoons in the Schoharie Valley,”Journal of the American Revolution, August 12, 2013.

[14]Thomas Young Seymour Pension Petition, Revolutionary War Pensions, National Archives and Records Administration, W. 19,000.

[15]“Returns of Seven Troops of Light Horse of the State of Connecticut Commanded by Ebenezer Backus,”Revolutionary War Rolls.

[16]“Payroll of Captain Samuel Hall’s Company Light Horse in Major Ebenzer Backus’s Regiment,”“Payroll of Captain Elijah Hyde’s Company Light Horse in Major Ebenzer Backus’s Regiment,” Revolutionary War Rolls.Tallmadge, Size Roll.

[17]Charles Snell, A Report on the Organization and Numbers of Gates’s Army, September 19, October 7, and October 17, 1777, Including an Appendix with Regimental Data and Notes (Philadelphia: National Park Service, 1951), p. 10.

[18]Nathaniel Barnett Pension Petition, Revolutionary War Pensions, R536.

[19]All pension petitions and rosters cited here are from Revolutionary War Pensions.

[20]Borden Mills, “Albany County’s Part in the Battle of Saratoga,”Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association 15 (1916), 206.

[21]Snell, A Report on the Organization and Numbers of Gates’s Army, 1, 34.

[22]William Upham, A Memoir of General John Glover of Marblehead (Salem: Charles W. Swazey, 1853), 100.

[23]Enos Hitchcock, “Diary of Enos Hitchcock, D. D., a Chaplain in the Revolutionary Army.”Publications of the Rhode Island Historical Society, vol. 28 (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1900), 130.

[24]Henry Dearborn, “Journal of Henry Dearborn, from July 25, 1776 to December 4, 1777,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 3 (1886), 105.

[25]Orderly Book, 15th Massachusetts, Glover’s Brigade, Library of Congress Manuscript Division.

[26]Dean Snow, 1777: Tipping Point at Saratoga (New York: Oxford University Press. 2016), 358.

[28]John Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition from Canada (London: J. Almon, 1780), 110, tab. xvi.

[29]Snell, A Report on the Organization and Numbers of Gates’s Army, 24-25. Upham, A Memoir of General John Glover, 100. Hitchcock, Diary of Enos Hitchcock, 120. Dearborn, Journal, 105.

[30]Snell, A Report on the Organization and Numbers of Gates’s Army, 13.

[31]Frank Goodway, The Saratoga Campaign of the Revolutionary War: Tables of Organization, saratoganygenweb.com/Sarato.htm#G2.

[33]Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition from Canada, Appendix xcvii.

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...