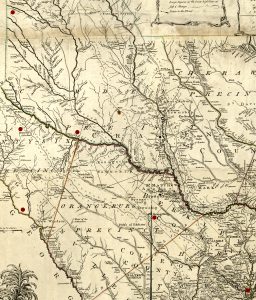

On or about November 19, 1781, a Loyalist officer named William Cunningham and his regiment of approximately three hundred men rode toward Hayes Station, a fortified log home, or “blockhouse,” in the Little River District, surrounding western South Carolina’s Little River primarily in what is now Laurens County, South Carolina.[1]

Now commanding the outpost was Patriot colonel Joseph Hayes with a small company of approximately twenty-three men, along with some women and children. Among them were two sons of the regiment’s former commander, Col. James Williams: Daniel, eighteen, and Joseph, fourteen. James Williams had died from wounds received at Kings Mountain the previous year.

One account describes Hayes as “a bold, inexperienced, incautious man,” although by this time he was the veteran of several militia campaigns and had served as colonel of the Little River Regiment since Williams’ death.[2] On this day he was apparently warned by his neighbor, William Caldwell, who had observed smoke rising from the homes Cunningham burned as he approached. But Hayes was engrossed in his blacksmith’s work, “making a cleat to hold a lady’s netting,” and disregarded Caldwell’s warning. When Cunningham arrived shortly thereafter, Hayes and his company were caught by surprise, barely escaping inside the blockhouse with their families.[3]

Two men were killed in the ensuing firefight, one a Loyalist, the other a Patriot, until Cunningham set fire to the outpost’s roof with a flaming “ram-rod tipped with flax, saturated with tar” shot out of a musket. Hayes’s only option was to offer surrender on the condition that his families be released and his men treated as prisoners of war. Whether or not Cunningham accepted these conditions has been lost to time. As the defeated Patriots filed out of their flaming outpost, Cunningham separated out the women and children, as well as a Patriot named Reuben Golden to whom Cunningham “was indebted for some past favors,” and perhaps two other men.[4]

He then ordered Hayes and Daniel Williams hung from the pole of a fodder stack. According to one account, Joseph Williams had known Cunningham “from infancy” and called out to his acquaintance, “Captain Cunningham how shall I go home and tell my mother that you have hanged brother?” Cunningham responded by hanging Joseph as well, but when the pole broke, and the three Patriots tumbled to the ground, Cunningham “with his sword literally hewed them in pieces.”[5]

Cunningham then turned upon the rest of his prisoners and “continued on them the operations of his savage barbarityuntil the powers of nature being exhausted, and his enfeebled limbs refusing to administer any longer to insatiate his fury, he called upon his comrades to complete the dreadful work, by killing whichsoever of the prisoners they pleased.”[6]

Hayes Station was perhaps the most blood-soaked event of Cunningham’s backcountry raid, now known as “The Bloody Scout.” And though we can hardly imagine a scene more terrifying than Cunningham hacking to death defenseless men until collapsing from exhaustion into a pool of blood and human parts, there was much more murder and violence to come. Today, the sociological impact of the Bloody Scout endures in South Carolina’s northwestern corner known as the “Upstate,” where the name “Bloody Bill” Cunningham symbolizes a legacy of civil war that still influences the region’s culture.

Who was William Cunningham? And what prompted the Bloody Scout? Any attempt to document his raid must necessarily be based on anecdotal accounts, collected mostly by eighteenth and nineteenth century historians. What follows is an attempt to provide a narrative account of the Bloody Scout. Its timeline is the result of research by historian John C. Parker.First, however, is a brief biography of Cunningham and exploration of the historical context for his raid.[7]

William Cunningham

According to the nineteenth century historian J.B.O. Landrum, William Cunningham was born near Ninety-Six in the present-day county of Abbeville, South Carolina, although historian Robert Stansbury Lambert lists his birthplace as Ireland. In early manhood, Landrum reports, Cunningham “was promising and influential.”[8]

Most sources describe him as a cousin of Robert and Patrick Cunningham, prominent Loyalist brothers who came from east Pennsylvania to settle in the region of South Carolina near Ninety Six, what was then the most significant settlement in western South Carolina. In November 1775 Robert Cunningham’s arrest for refusing the pledge of allegiance to the Patriot cause, known as the “Pledge of Association,” led to the “Battle of Ninety Six,” where Patrick Cunningham’s Loyalist militia attacked Patriot forces under Andrew Williamson in retaliation, becoming the American Revolution’s first military engagement in South Carolina. Both Robert and Patrick would go on to command Loyalist regiments later in the war, Patrick as a colonel and Robert as brigadier general. Nineteenth century historian Lorenzo Sabine describes Robert Cunningham as “one of the most prominent Loyalists of the whole South.”[9]

One of the best biographical sources available on William Cunningham appears in the published papers of Loyalist Samuel Curwen, edited by George Atkinson Ward. There, Cunningham is described as a young man of nineteen in 1775. “His political opinions leaned to the Whig side, and, being a great favorite with the young men in the district … he exercised considerable influence over them.” At the beginning of the war, Cunningham enlisted in the Patriot company of John Caldwell, suggesting his political sympathies initially opposed those of his cousins, Robert and Patrick. But political allegiances in the South Carolina interior, or “backcountry,” were fluid at this time. Early in the war, Robert and Patrick were not so much steadfast Loyalists as they were opponents of the heavy-handed tactics of the Provincial Congress, which coerced citizens into signing the “Association” pledge or face social and political retribution.

When Caldwell’s company was sent to James’s Island near Charleston, William Cunningham attempted to resign, complaining that he had enlisted on the condition that he “should have a right to retire” if the company was ordered away from western South Carolina. “Thinking to strike terror into his men, and thereby have them more under control,” Caldwell instead had Cunningham arrested and court martialed for mutiny. When Cunningham was acquitted and allowed to return to the backcountry, “Caldwell became an object of hatred and contempt,” writes Curwen.[10]

Cunningham then participated in Col. Andrew Williamson’s campaign against the Cherokee in 1776, where a combined militia of Patriots and Loyalists sacked, plundered, and burned several Cherokee towns. Afterwards, however, Cunningham “declared that . . . he was determined to continue no longer in the service of the Whigs,” a repudiation for which he was apparently ostracized and persecuted.[11] Curwen writes that after this declaration “he was hunted more like a wild beast than a man, and his only secure place of rest was in the deepest recess of some all but impenetrable forest.”[12] Particularly active in these persecutions was Captain William Ritchie, who had served with Cunningham in Caldwell’s company.

Cunningham escaped to the vicinity of Savannah, Georgia, in 1778, where he received news that Ritchie had abused and murdered his epileptic brother. Lacking a horse, Cunningham set out on foot to seek his revenge and received news on the way that Ritchie had also abused Cunningham’s bedridden father. When Cunningham finally arrived at Ritchie’s home, Ritchie “tried to escape over the fence, but Cunningham shot him down . . . From this period till the end of the war, Major Cunningham’s life was passed in a series of wild adventures.”[13]

Following Ritchie’s death, Patrick Cunningham gifted to William a thoroughbred horse named “Ringtail” for a white ring around his tail. Shortly thereafter, a Patriot militia captain named Samuel Moore abused the wife of Cunningham’s brother, Andrew, while he was searching for Cunningham. Tracking Moore for two days, Cunningham finally caught sight of him on a nearby hilltop. Moore “immediately put spurs to his horse then considered the fleetest in the country.” After a chase of about a mile and a half, “Cunningham overtook him and . . . cut him down with sword,” bringing “forth Ringtail’s great powers of strength and speed—but very many were the occasions afterwards, on which Major Cunningham was indebted entirely to his horse for his safety.”[14]

War in South Carolina

Like so much of South Carolina’s history during the American Revolution, the story of William Cunningham hinges on the capture of Charleston in May 1780, which re-established British control over its former colony. South Carolina’s Loyalists were now empowered to take revenge for the type of persecution and violence that Cunningham’s brother and father had suffered at the hands of men like Ritchie. “Under the sanction of subduing rebellion, private revenge was gratified,” writes Ramsay. “Rapine, outrage, and murder became so common as to interrupt the free intercourse between one place and another.”[15]

The Loyalists may have temporarily had the upper hand, but the violence went both ways. Writing a year before Hayes Station on the conditions in South Carolina, Continental Gen. Nathanael Greene complained, “The Whigs and Tories pursue one another with the most relentless fury killing and destroying each other wherever they meet.”[16]

Cunningham is listed as a captain in Patrick Cunningham’s Loyalist regiment in a roster dated June 14, 1780.[17] The famous Carolina Loyalist Col. David Fanning wrote in his memoir that he and William Cunningham, operating in joint command of a “body of men,” personally chased Col. James Williams from his home on Little River following the capture of Charleston. “Col’n Williams got notice of it, and pushed off; and though we got sight of him, he escaped us,” Fanning wrote. This was the same James Williams whose sons Cunningham would later murder at Hayes Station.[18]

The memoir of Maj. Joseph McJunkin claims William Cunningham was in command of the Loyalist regiment that raided and scattered the camp of Patriot militia colonel Thomas Brandon of the 2nd Spartan, or Fair Forest Regiment, on or about June 8, 1780, an action commonly referred to as “Brandon’s Defeat.”[19]

As part of Patrick Cunningham’s loyalist regiment, William Cunningham likely served with Ferguson at the battle of Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780.[20] If true, he would have witnessed the slaughter of perhaps as many as one hundred of his fellow Loyalists after they attempted to surrender. He also may have witnessed the vigilante execution of nine Loyalist prisoners at Biggerstaff’s Old Field, North Carolina, a week later, then endured further abuses before likely escaping as the Patriots attempted to march their Loyalist prisoners toward Salem, North Carolina.

By July 1781 the momentum of the war had turned again. That month the British abandoned their outpost at Ninety Six, taking many Loyalists families from the surrounding region with them as refugees, including Robert and Patrick Cunningham. Now a major in command of a company of approximately forty men, William Cunningham stayed behind, raiding Patriot settlements in the Little River District, capturing several rebel blockhouses, killing five, and plundering until he was chased away by the Patriot militia.[21]

Meanwhile, Loyalists who remained behind following the British evacuation faced yet another round of reprisals from their Patriot neighbors. “Atrocities would be expiated by fresh atrocities,” explains the historian Robert D. Bass. “No man would be safe if he had worn the king’s uniform, accepted a commission in a Royal regiment or had served as magistrate for his majesty.”[22] And not all Loyalists who evacuated the Ninety Six region did so by their own free will. As early as July 19, Patriot militia general Andrew Pickens reported that his forces had escorted several Loyalist families to British lines. Ostensibly, these measures were taken for the Loyalists’ own safety, although they no doubt included some plundering and violence. Meanwhile, Pickens ordered militia colonels LeRoy Hammond and Robert Anderson to raise regiments “for the purpose of suppressing Enemies of Every kind, detecting and regulating plundering parties of Every Denomination.”[23]

By September 1781, William Cunningham and his Loyalist company had reached the British defenses at Charleston, where news filtered into the city about fresh persecutions endured by Loyalist families. These persecutions only increased when on September 27, 1781, South Carolina governor John Rutledge issued a proclamation ordering the forced removal of Loyalists’ families who either refused parole or where ineligible for it.[24]

These reports prompted William Cunningham to raid in the Little River District again, killing eight Patriots, capturing several Patriot blockhouses, and recruiting sixty additional followers in late September and early October, until retreating to the Charleston area again to recruit and regroup. British records show him to have been in Charleston on October 23, when he received pay for his militia service.[25]

The Bloody Scout

The stage now was set for The Bloody Scout, as William Cunningham and other Loyalist soldiers in Charleston continued to receive news about abuses of Loyalist families. As J.B.O. Landrum wrote in 1897, “It is impossible to know the extent” of Cunningham’s atrocities during the Bloody Scout. “It is only here and there we find recorded the most prominent of his acts of cruelty.”[26] Sources suggest retaliation against Patriot commanders Leroy Hammond, Robert Anderson, Joseph Hayes, Sterling Turner, and Benjamin Roebuck was its primary objective.[27] In late October or early November 1781, William Cunningham recruited a regiment of approximately three hundred exiled Loyalists.[28] To avoid detection, this regiment departed Charleston in at least two smaller groups, one under command of Loyalist militia leader Hezekiah Williams.[29]

After passing through lower South Carolina, Cunningham and Williams reunited in the vicinity of Orangeburg. At Rowe’s Plantation, they skirmished on November 13 with Patriot militia under direct command of Maj. John Moore and overall command of Thomas Sumter. “I am at a loss to Conceive What the Intentions of the Troops [Cunningham’s] are,” Sumter admitted to Nathanael Greene.[30] A few days later, Sumter updated his report to Greene, writing that Cunningham and Williams were “said to be heading for Ninety Six or the Indian Nation.”[31]

Following the skirmish at Rowe’s Plantation, the Loyalists split again, with William Cunningham’s company moving toward the Saluda River and Hezekiah Williams’ traveling toward the Savannah River.[32] At a community called Mount Willing, near modern-day Saluda, Williams and his men plundered local Patriot settlers, taking with them a small herd of stolen cattle. Williams then moved twenty-six miles east to Tarrar Spring in present-day Lexington County, while a smaller detachment under Capt. William Radcliffe moved north.

Capt. Sterling Turner’s Patriot militia tracked Radcliffe across the Saluda River and surprised him near the community of Mount Willing, killing Radcliffe and several of his men. Turner then turned east to follow Hezekiah Williams to Tarrar Spring, where they skirmished on November 16, and Turner agreed to let Williams’ company leave unharmed if they returned the stolen cattle.[33]

While Turner camped that night at Cloud’s Creek with approximately twenty men, William Cunningham reunited with Hezekiah Williams. Enraged by the killing of Radcliffe, Cunningham tracked Turner and attacked his camp on November 17. Taking refuge inside an abandoned house, Turner’s Patriots exchanged fire with Cunningham’s men for almost two hours while Turner attempted to negotiate a surrender. During the firefight, Turner lost six men. Finally, his ammunition expended, Turner offered surrender.

According to historian John Belton O’Neall, “It was a rule of the company, that after Cunningham had selected his victims, each member might select the objects of his vengeance. Sometimes mercy ruled the hour, and a soldier was allowed to save a friend or acquaintance.”[34] In this case, Cunningham offered no quarter, ordering the remainder of Turner’s force put to death by the sword, except for one who escaped and one who was spared because he was mistaken for a Loyalist sympathizer. “The Captain’s [Turner’s] head was cut off and one Butler, a man who had been remarkably active, was tortured with more than savage cruelty. Both his hands were cut off while alive and it is said many other cruelties committed on him shameful to repeat,” recounted Col. LeRoy Hammond in a report to Nathanael Greene.[35]

After massacring Turner, Cunningham crossed the Saluda River at Saluda Old Town Ferry and rode toward the house of Capt. John Towles, who had served with Cunningham in John Caldwell’s company in 1775. Historian John C. Parker states Towles had been engaged in the plundering of Loyalist cattle and in driving Loyalist women and children from their homes. On or around November 18, Towles learned of Cunningham’s approach and fled to the woods for hiding. However, a Loyalist named Ned Turner tricked Towles’s wife with a false offer of protection. When she sent her young son to gather Towles, Turner followed him to Towles’ hiding place and murdered Towles in cold blood while his child was watching.[36]

The same day, Cunningham’s regiment traveled to the nearby blacksmith shop of Capt. Oliver Towles, John Towles’ brother. There, they had their horses shod before murdering Towles, his son, and a young enslaved man, then burning all the buildings.

Cunningham then rode to the home of Maj. John Caldwell.[37] In the account of J.B.O. Landrum, attributed to an eyewitness, Cunningham himself hailed his old associate from the gate outside Caldwell’s house. When Caldwell emerged, Cunningham “drew a pistol and shot him dead in the presence of his wife, who fainted as she saw him fall.”[38] In another account, it was Cunningham’s men who shot Caldwell, and Cunningham “affected to deplore the bloody deed . . . with tears” upon discovering it. “Yet in the next instance, Caldwell’s house, by Cunningham’s orders, was in flames, and his widow left with no other covering than the heavens, seated by the side of her murdered husband.”[39]

The following day, November 19, 1781, Cunningham arrived at Hayes Station, approximately ten miles from Caldwell’s house. Following the bloodbath there, Cunningham camped that night at the nearby mill of Hugh O’Neal on the Little River, burning it the following morning. O’Neal hid in the woods nearby, and the following morning “he and some other of the neighbors committed to earth the mangled bodies of the slain at Hayes’ Station. Two large pits constituted the graves of all who fell there.”[40]

Cunningham now headed west toward the militia outpost of LeRoy Hammond at Anderson’s Mill on the Saluda River, a site now submerged under Lake Greenwood. Though the outpost was unmanned, Cunningham burned the mill on or around November 20. By now, several Patriot militia companies were in pursuit of Cunningham, including a company under Capt. Samuel Moore. On the way to Anderson’s Mill, Cunningham set an ambush for Moore at Swancey’s Ferry on the Saluda River, killing Moore and another Patriot soldier, with the rest of Moore’s men swimming the river to escape.[41]

Cunningham then moved north, into the Spartan District, or what is modern-day Spartanburg County. On or around November 21, Cunningham’s regiment arrived at Walnut Grove, the home of Charles Moore. Although Moore does not appear to have participated in militia operations during the American Revolution, Cunningham may have been in search of family members who were active in the Patriot militia regiment of Benjamin Roebuck.

At Walnut Grove, the Moore family was tending a wounded Patriot militia officer named Patrick Steadman, who was perhaps the fiancé of one of Moore’s daughters. In some accounts, Steadman was rendered immobile within a bundling bag, a type of Colonial-era chastity belt used when unwed paramours slept within the same household. Visiting Steadman that day were two of his fellow Patriot militia soldiers. Upon arriving at Walnut Grove, Cunningham’s men murdered Steadman in his bed and shot down his two comrades as they attempted to flee the property.[42]

Cunningham then moved north by northeast to Lawson’s Fork, a tributary of the Pacolet River. Here was the home of James Wood, a prominent Whig who had served as the commissioner of sequestered property from December 1780 to May 1781.[43] Wood was either hung or shot, according to different accounts, in the presence of his wife in the yard of his house. This was probably the same day Cunningham killed Steadman at Walnut Grove. Over the next two days, Cunningham and his men also murdered in similar fashion John Wood, Hilliard Thomas, John Snoddy, and a “Mr. Lawson,” shooting them down as they stepped out of their houses to greet Cunningham’s party. That night, Cunningham and his men burned Wofford’s Ironworks on Lawson’s Fork, a prominent local meeting place that had played an important role in the Second Battle of Cedar Springs (or the Battle of the Peach Orchard) the year before.[44]

Cunningham was now being pursued by Patriot militia companies under command of John McClure and John Barry and moved south by southeast into present-day Union County. It was probably around this time that he killed Edward Hampton, then serving as a lieutenant colonel under Thomas Sumter, but probably known to Cunningham through their mutual service in Andrew Williamson’s Cherokee expedition. According to tradition, Cunningham received news Hampton was traveling in the area and had stopped at a nearby house for breakfast. Cunningham or his men stormed the house and shot down Hampton at the table where he ate.[45]

Several other Cunningham murders recorded in folkloric accounts probably occurred on or around this same day, either November 23 or 24. James Knox and Thomas Dunlap were both members of Roebuck’s militia regiment killed at their homes by Cunningham.[46] John Boyce was a Patriot militia soldier who lived on Duncan’s Creek in southern Union County. Probably after the killing of Knox and Thomas, Cunningham surrounded his house, but Boyce escaped by running straight through the Tory horses and taking cover in a thick wood, after deflecting a blow from Cunningham’s sword with his hand, nearly severing three of his fingers. After Cunningham left, Boyce rode to the house of his militia commander, Capt. Christopher Casey, and mustered a small company to pursue Cunningham. At Duncan’s Creek, Casey and his men captured a few of Cunningham’s stragglers and hung them at the intersection of Charlestown Road and Ninety-Six Road.[47]

In late November or early December, with several Patriot militia units now in pursuit, Cunningham once again split his command with Hezekiah Williams, then split his command again, ordering Capt. John Crawford to harass settlers in the Long Cane settlements near the Savannah River. Near modern-day Edgefield, Crawford murdered a Patriot named George Foreman and his two sons before destroying abandoned White Hall, the plantation home of Patriot colonel Andrew Williamson that had been converted into a militia outpost.

Crawford then rode to Andrew Pickens’s blockhouse on McCord Creek and surprised a convoy of wagons guarded there by Capt. Moses Liddell. He burned the wagons and captured or killed several of Liddell’s men. Crawford escaped into the Cherokee territory, turning over his prisoners to the Cherokee for death by torture. Among them was Andrew Pickens’ brother, John Pickens, who was singled out by the Cherokees for an especially barbarous death.[48]

Aftermath

The Bloody Scout was now concluded but Cunningham still had to retreat safely to Charleston. On his return, Cunningham had with him about 150 men. On the night of December 19, he stopped on the Edisto River, ordering his men to set up several small camps to guard against attack from pursuing Patriot militia. On the morning of December 20, Andrew Pickens and his militia crossed the Edisto near Orangeburg and attacked one of these camps, slaughtering all the twenty men there, but alerting Cunningham and the rest of his men, who escaped safely and returned to Charleston.[49]

It is said Cunningham’s beloved mount Ringtail died from exhaustion shortly after reaching Charleston, causing the murderous “Bloody Bill” to break down in grief. According to Curwen, Cunningham “had him buried with all the honors of war—the bells of Charleston tolled and vollies were fired over the hero of many fights.”[50]

Ringtail’s bizarre funeral ends the story of the Bloody Scout. Historian Robert C. Parker estimates the Patriot death toll of the Bloody Scout was “at least” seventy-nine.[51] Historian Robert Lambert suggests Cunningham’s historic impact stems, in part, from the timing of his raid. Shortly after the Bloody Scout concluded, in January 1782, South Carolina’s general assembly reconvened for the first time since the surrender of Charleston in May 1780. There, Patriot leaders such as Pickens, Sumter, and Hammond presumably discussed Cunningham’s Bloody Scout, where the gossip was overheard by David Ramsay, a physician who also attended the general assembly. Three years later, Ramsay would publish an account of Cunningham’s exploits in The History of the Revolution in South Carolina.[52]

Meanwhile, Cunningham remained safe in Charleston, protected by the British occupation of the city that lasted until December 1782. By then Cunningham had escaped to Florida, where many South Carolina’s Loyalists took refuge in the final months of the war. He may have eventually settled in England, where according to Curwen, Parliament voted him a major’s half-pay military pension.[53]

For a man who played a relatively insignificant role in the American Revolution, William Cunningham is perhaps one of its most famous figures in western South Carolina, where his antics are the subject of historic reenactments and local history exhibits.[54] This phenomenon is hard to quantify, except to say the name “Bloody Bill” appears to evoke the war’s factional nature in this region, and the sense of terror and chaos that accompanied it. Without veering too deeply into sociological speculations, I can only say that his presence is still palpable here, embedded in the cultural DNA. Though he may be only a curiosity in other parts of the United States, if he his known at all, in the South Carolina Upstate, it seems there will always be Bloody Bill.

[1]John Belton O’Neall, The Annals of Newberry, Historical, Biographical and Anecdotal (Charleston, SC: S.G. Courtenay and Co. Publishers, 1859), 269. Also J.B.O. Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History of Upper South Carolina (Greenville, SC: Shannon & Co. Printers and Binders, 1897), 350-351.

[2]Bobby Gilmer Moss, Roster of South Carolina Patriots in the American Revolution (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1983), 429.

[4]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 350.

[6]David Ramsay, The History of the Revolution of South Carolina, Vol. 2 (Trenton, NJ: Isaac Collins, 1785), 273.

[7]John C. Parker, Parker’s Guide to the Revolutionary War in South Carolina (West Conshohocken, PA: Infinity Publishing, 2013), 481-482.

[8]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 342. Also, Robert Stansbury Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution, 2nd Edition (Clemson, SC: Clemson University Press, 2010), 147.

[9]Lorenzo Sabine, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1864), 1:346.

[10]Samuel Curwen, Journal and Letters of the Late Samuel Curwen, 3rd Edition, ed. George Atkinson Ward (New York: Leavitt, Trow & Co., 1845), 639.

[11]“Papers of the First Council of Safety of the Revolutionary Party in South Carolina, June-November 1775,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, 2 (July 1901), 176. Also, O’Neall, Annals, 252.

[15]David Ramsay, History of South Carolina from Its First Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808 (Newberry, SC: W.J. Duffie, 1858), 256.

[16]“Nathanael Greene to Samuel Huntington,” December 28, 1780,” in Richard K. Showman and Dennis Conrad, eds., The Papers of Nathanael Greene (hereafter NG), 7:9. “Greene to Richard General Robert Howe,” NG, 7:17.

[17]Bobby Gilmer Moss, Roster of the Loyalists in the Battle of Kings Mountain (Blacksburg, SC: Scotia-Hibernia Press, 1998), 20-21.

[18]David Fanning, The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning: A Tory in the Revolutionary War With Great Britain; Giving an Account of His Adventures in North Carolina, from 1775 to 1783 (New York: Joseph Sabin, 1865), 11.

[19]“The Memoir of Major Joseph McJunkin,” sc_tories.tripod.com/memoirs_of_major_joseph_mcjunkin.htm.

[20]Moss, Loyalists in the Battle of Kings Mountain, 20-21.

[21]Andrew Pickens to Nathanael Greene,” July 17, 1781, NG, 49-50.

[22]Robert D. Bass, Ninety Six: The Struggle for the South Carolina Back Country (Orangeburg, SC: Sandlapper Publishing Co., 1978), 416-417.

[23]“Andrew Pickens to Nathanael Greene,” July 17, 1781, NG, 9:48-49.

[24]“Proclamation of John Rutledge,” September 27, 1781, in R.W. Gibbes, ed., Documentary History of the American Revolution in 1781 and 1782(Columbia, SC: Banner Steam-Power Press, 1853), 175-178.

[25]Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists, 147-148. Also “Note 4,” NG, 9:50.

[26]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 347.

[27]Ibid. Also Curwen, Journal, 644.

[29]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 208-209.

[30]“Thomas Sumter to Nathanael Greene,” November 14, 1781, NG, 9:575-576.

[31]“Thomas Sumter to Nathanael Greene,” November 17, 1781, NG, 9:586.

[32]“Thomas Sumter to Nathanael Greene,” November 23, 1781, NG,9:615.

[33]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 315, 341.

[34]John Belton O’Neall, “Random Recollections of Revolutionary Characters and Incidents,” Southern Literary Journal and Magazine of the Arts, 4(1) (July 1838), 40-45.

[35]“Col. LeRoy Hammond to Nathanael Greene,” December 2, 1781, NG, 9:651.

[36]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 348. Also, Moss, Roster of South Carolina Patriots, 937.

[37]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 351.

[38]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 349.

[40]O’Neall, “Random Recollections,” 40-45.

[41]“Pension Application of George Watts” (W1009). revwarapps.org/w1009.pdf.

[42]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 352.

[43]Moss, Roster of South Carolina Patriots,1010.

[44]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 352-357.

[45]Moss, Roster of South Carolina Patriots, 408. Also Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston, SC: Walker & James, 1851), 454.

[46]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 158.

[47]Landrum, Colonial and Revolutionary History, 351-352.

[48]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 212. Also, Patrick O’Kelley, Nothing But Blood and Slaughter, Vol. 3 (Charleston, SC: Blue House Tavern Press, 2005), 404-405.

[49]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 373.

[51]Parker, Parker’s Guide, 482.

[52]Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists, 149.

[53]Ibid, 189. Also, Curwen, Journal, 647.

[54]Each fall, the Spartanburg County Historical Society performs a reenactment of Cunningham’s raid at Walnut Grove. Walnut Grove is open to visitors as a house museum (www.spartanburghistory.org/).

One thought on “William “Bloody Bill” Cunningham and the Bloody Scout”

Cunningham made a second trip. William Butler, son of Capt. James Butler who was murdered by Bloody Bill at Clouds Creek, obtained Cunningham’s sword after a chase. The sword is on display in Columbia.