Colonel Samuel Bryan is thought to be the highest-ranking Loyalist officer to remain in the United States after the Revolutionary War. Despite being a high-ranking British officer in command of hundreds of men, little is known about him and the militia unit he commanded. With the arrival of British regulars in the Carolinas in 1780, Bryan came out of hiding and fled to British lines where he was put in command of a Loyalist militia regiment named the North Carolina Volunteers. While historiography of the period relegates Bryan and his regiment as minor participants in the military contest, it was another aspect of the war for which Bryan acquired a degree of infamy. In the post-Yorktown period, Bryan and two of his officers were defendants in the highest profile North Carolina treason trial of the era. Given their relatively high ranks, the men were not confined long, instead becoming bargaining chips in prisoner exchange negotiations among North Carolina governors, Gen. Nathanael Greene, and British Gen. Alexander Leslie. Ultimately exchanged, the men found themselves with the same uncertainties facing other Loyalists at the end of the war. Would they be allowed to remain in the United States? If so, would they be persecuted or imprisoned? Would they be able to keep (or more likely regain) their confiscated property? For Bryan, his officers, and other Loyalists, there were no clear answers to these questions in 1782. This uncertainty flung them to the near and further reaches of the British realm.

Samuel Bryan was born in Pennsylvania between 1721 and 1726. His father, Morgan, in the 1740s purchased 2,200 acres of land on the forks of the Yadkin River that became known as the Bryan Settlement. In what would eventually become Rowan County, North Carolina, the Bryan family went on to establish a double (perhaps triple) connection, by marriage, to pioneer and folk legend Daniel Boone whose family lived on nearby tracts of land.[1] Samuel’s niece, Rebecca, married Boone. Samuel’s brother, William, married Boone’s sister, Mary.[2] Another niece possibly married Boone’s brother, Edward. These Bryan-Boone family units were among the first of European lineage to establish settlements in the Kentucky territory before the war.

Samuel Bryan cast his lot with Britain early in the revolutionary conflict. In May 1775, he was one of 194 men signing a petition of loyalty to the Crown. The men noted in their address to North Carolina Royal Governor Josiah Martin “to continue [to be] his Majesty’s loyal subjects and to contribute all in our power for the preservation of the public peace and that we shall endeavour to cultivate such sentiments in all those under our care.”[3] By January 1776, the political environment in North Carolina for loyal Americans had changed considerably. A nearby Moravian diarist reported the “Bryants” (as they were often called) had gone into hiding.[4] That month Governor Martin, who had fled to the sloop Scorpion in the Cape Fear River, granted commissions to Samuel, his brother William, and twenty-four other men to raise companies of fifty men each and march toward Brunswick on the southeast North Carolina coast.[5] This assemblage of Loyalists was met on their march by Patriot militia and defeated at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge in February 1776. There is no indication that Samuel Bryan was at the battle, but it is possible he and the men he raised were in the area or on their way to join the larger body of Loyalists. Bryan, in his 1783 claim with the British government, noted raising men to assist the “Scottish revolt” but said they were defeated, resulting in his going back into hiding.[6]

In 1777, Samuel Bryan left North Carolina for New York to converse with now former Gov. Josiah Martin and Gen. William Howe, returning with “a number of proclamations and great encouragement” for Carolinians to persist in their loyalty.[7] Open support for the Crown became essentially illegal and more dangerous during this timeframe. In late 1777, the state government required all males over sixteen years of age to take an oath of allegiance to the new government. Those that refused were required to leave the state or risk having their property confiscated.[8] Samuel and eleven other Bryans are listed among men in Rowan County who were called to the court in 1778 to have their property confiscated.[9] These confiscations (or the threat of them) caused several of Bryan’s relatives to relocate to Kentucky. His brother, Morgan, was one of those who did so after signing the oath of allegiance in 1778.[10]

In June 1780, after successfully hiding out for several years, Samuel Bryan and what eventually became 800 Loyalists made a perilous escape from the forks of the Yadkin River to British forces in South Carolina. The impetus for this flight was the actions of Col. John Moore who had, against Gen. Charles Cornwallis’s orders, assembled 1,100 Loyalists who were met and defeated by North Carolina militia at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill. After the battle, Gen. Griffith Rutherford’s militia and a detachment of state cavalry under Maj. William R. Davie moved northeast towards the Yadkin River in search of Bryan and his Loyalists. Fleeing eastwards across the Yadkin and then south, Bryan and most of his contingent adeptly avoided engagements with the North Carolina militia and arrived at a British outpost in Cheraw Hill, South Carolina in late June 1780.

General Cornwallis was not exactly pleased to hear of Bryan within his lines, noting that he “had promised to wait for my orders, lost all patience and rose with about 800 men.”[11] Other British officers were not so harsh in their assessments. Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon recalled Bryan as a “shrewd man . . . with great influence.”[12] Charles Stedman, Philadelphia loyalist and British army commissary, noted of Bryan’s men that there “never was a finer body of men collected; strong, healthy, and accustomed to the severity of the climate.” Stedman went on to add that many of them, although men of property, were clothed in rags and had been living in the woods for months to avoid American persecution.[13] Josiah Martin, now accompanying Cornwallis’s army, argued Bryan’s men were great proof of his claims of Loyalist support in North Carolina.[14]

Were Bryan and his men the kind of “militant Loyalists” that British leadership had hoped to find in the American South? For the most part they were not. Despite the pressing need for Loyalist militia during the latter half of 1780, Bryan’s newly formed militia regiment was only sparingly referenced in the hundreds of letters in British correspondence during this time. The most prevalent description of Bryan and his men was not as soldiers but as “refugees.” Josiah Martin, while initially pleased to see so many North Carolinians join the loyal militia, had to ultimately concede that they primarily fled to safety within British lines to avoid being drafted into the Patriot militia.[15] Rawdon reported the same to Cornwallis, noting that “they had been drafted to serve in the militia and refusing to march had no alternative but joining us or going to prison.“[16] Andrew Hamm of the North Carolina Volunteers later claimed that he was, for a short time, in the North Carolina militia but escaped.[17] Cornwallis, Stedman, and Lt. John Money in 1780 all referred to Bryan’s men as “refugees” in their correspondence. There are a few indications by British writers that the militia as whole now with the army were a burden. Cornwallis cautioned one of his officers about undertaking to “supply too many useless mouths.”[18] In September 1780, when he was about to invade North Carolina, Cornwallis complained of severe supply problems and of too many “mouths to feed.”[19] These problems were so severe that the invasion was halted while supplies were gathered from other districts. If Bryan’s militia were indeed a burden, their presence was both counterproductive and ironic as one of the main objectives of the first invasion of North Carolina was to come to the aid of Loyalists there.

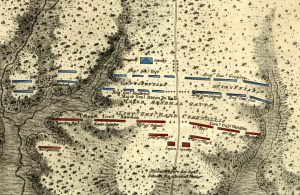

Bryan’s North Carolina Volunteers played no significant role in the battles of 1780 in the Carolinas. They were, however, involved in three engagements during an eighteen-day period. On July 30, 1780, about 400 North Carolina Volunteers were camped away from the main body of troops at Hanging Rock, a British outpost thirty miles north of Camden, South Carolina. At dawn they were surprised and routed by a detachment of North Carolina state cavalry and militia under the command of Maj. William R. Davie. A week later at the second Battle of Hanging Rock, the unit and the rest of the camp were surprised again by a larger force of Davie’s men, Col. Robert Irwin’s militia from Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and South Carolina militia under the overall command of Gen. Thomas Sumter. Just ten days later at the Battle of Camden, the North Carolina Volunteers were placed in reserve behind Lt. Col. John Hamilton’s Royal North Carolina Provincial Regiment on the far left of the British line. Of the 322 North Carolina Volunteers present, only two were wounded and none were killed.[20] Col. Samuel Bryan is not listed as having been in the action, the highest ranking officer for the militia being a lieutenant colonel.[21] Afterward, Bryan’s men returned to their largely logistical role in Cornwallis’s army. Commissary Stedman reported that the militia performed the all-important duty of constantly gathering provisions and “threshing” wheat for the army. In the fall of 1780, many Loyalist militia deserted. Stedman wrote that during Cornwallis’s retreat to Winnsboro in October 1780 the militia were “maltreated, by abusive language, and even beaten.”[22] After Camden, Bryan’s status as a “Colonel” became only “nominal,” he and his men now fell under the overall command of Lt. Col. Hamilton.[23]

From October 1780 to June 1781 there is little and then only conflicting information in British records about the North Carolina Volunteers. In the available muster rolls, the unit is noted only on a few occasions and never with the Royal North Carolina Regiment. Where they are noted there is a drastic reduction in men from 800 in mid-1780 to 402 in May 1781. Colonel Bryan and a portion of North Carolina Volunteers were with Cornwallis in Virginia in mid-1781. In June, Cornwallis wrote in a letter to the commandant of Charleston, Gen. Alexander Leslie, that “Bryand and all those miserable people and some Negroes to the amount of 21 persons” were sent to Cape Fear (Wilmington) and Charleston.[24] Two North Carolina Volunteers, in their claims to the British government, noted they left Virginia for Charleston, then went to Wilmington until the regular troops evacuated, and then back to Charleston again.[25] At least sixty-six North Carolina Volunteers were among the prisoners taken at Yorktown. Also among the prisoners were at least seventy-eight men from the Royal North Carolina Regiment.[26]

What precisely Col. Samuel Bryan and two of his officers, Lt. Col. John Hampton and Capt. Nicholas White, were doing in the North Carolina backcountry in early December 1781 is unknown. But on December 9, Bryan was arrested on charges of “high treason” and “spying” and remanded to the Salisbury town jail. Within a few days Hampton and White were also arrested and joined Bryan there.[27] The three men were charged under the 1777 North Carolina treason statute which prohibited residents taking commissions in the British army, enlisting and encouraging others to join, and providing them with aid and intelligence.[28]

The trials of the three men started at the March 1782 Salisbury District Court session and was likely the highest profile trial in North Carolina during the war. Bryan and his men were not alone in their treason trials. At the Salisbury Court session that spring, there were 22 treason trials and over 160 more in 1783.[29] The mens’ trials involved the most prominent legal minds in the state at the time. The prosecution was led by North Carolina Attorney General Alfred Moore who later served as associate Justice of the US Supreme Court. The defense consisted of attorneys William R. Davie, Richard Henderson, William Kinchen, and John Penn. Penn was a member of the Second Continental Congress and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Henderson and Kinchen had previously been prominent members of the nascent North Carolina legislature. The inclusion of the last defense lawyer, Davie, must have struck those with any knowledge of his background as an extremely ironic and even odd choice. Davie was the cavalry officer who pursued Bryan from Rowan County to South Carolina and later attacked his men twice at Hanging Rock eighteen months prior. Davie’s defense of Bryan was said to have been such a “brilliant exhibition of his forensic ability” that afterward he had no rival in state as a criminal trial lawyer.[30]

Detailed minutes of the three trials are not extant but a few accounts from nineteenth century sources exist. The most salient point made by the defense was that Bryan was, in effect, a non-citizen and as such was not bound by the treason statute. The defense “admitted that Bryan had served ‘his Britanick Majesty whom the prisoner considered as his liege sovereign,’ and argued that Bryan ‘knew no protection from nor ever acknowledged any allegiance to the State of North Carolina’ so therefore he could not be guilty of treason against the State.”[31] Despite the best efforts of the defense the verdict was a foregone conclusion. On March 20 and 23 the three men were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. Shortly thereafter, Davie, Henderson, and Kinchen wrote to Gov. Thomas Burke asking for clemency, saying that the mens’ “execution would be a [poor] reflection on our Government.”[32] A subsequent judicial report sent to Burke by the presiding judges bolstered the request for a reprieve, noting that while the men were guilty under the provisions of the treason law their characters were not like that of numerous other notorious Loyalists. They were considered “very honest men” and there was “no proof of their having been guilty of any murders, house-burning or plundering.”[33] By April 6, 1782, Burke had granted a reprieve until May 10 which was enough time for a response from Gen. Alexander Leslie in Charleston about exchanging Bryan and his officers for American officer prisoners.[34] The same day, Burke also instructed Maj. Joel Lewis of the state troops to protect the men in jail from local “zealots” in the intervening time. One man, in his pension application, reported that it required the “utmost vigilance” of the guards to prevent the residents taking Bryan and his men from the jail and hanging them.[35]

Governor Burke’s reprieve began a three-month, at times confused and contentious, exchange of letters among himself, his successor Alexander Martin, Gen. Nathanael Greene, and General Leslie. On April 10, Leslie wrote that if Bryan and his officers were executed he would execute an equal number of American prisoners.[36] By May 1782 there was consensus among all that Bryan and his officers would be exchanged for militia officers of the state and not Continental officers. By May 12, the new governor of North Carolina, Alexander Martin, had sent the prisoners to GeneralGreene in South Carolina for exchange. Martin, frustrated at the lack of progress in the negotiations, countered Leslie’s original threat that he would carry out the death sentence for Bryan and his men if the process were not resolved more quickly.[37] Sometime in June 1782 Bryan and his fellow officers were finally exchanged. The event did not go as planned as Greene’s commissioner of prisoners exchanged Bryan, Hampton, and White not for North Carolina officers but prisoners from Virginia.[38]

In Charleston, Bryan and his officers rejoined their regiment and received their back pay.[39] Just a few months later in August-September 1782, the impending British evacuation of Charleston became evident to all including Greene’s army outside the city. There is some indication that the North Carolina Volunteers were officially disbanded during this period.[40] On October 10, 1782, an “Agreement on restoration of property” was signed between the South Carolina government meeting in Orangeburg and British authorities stipulating that the British would return all slaves to their former owners and that Loyalists who remained would not be arrested or their property taken.[41] Despite the protection offered, at least 9,121 people quit Charleston for England or other British territories. This number included 3,794 whites and 5,327 blacks. Forty-three percent went to Jamaica, forty-two percent to East Florida, and five percent to Nova Scotia. Other locations at less than five percent each included England, New York, and St. Lucia.[42] Surprisingly, after spending some much time hiding out in North Carolina during the war, Samuel Bryan made the fateful decision to remove himself and his family to East Florida.[43]

Gov. Patrick Tonyn noted a possible draw of such a sizable portion of southern Loyalists to East Florida may have been that “their property may be without much difficulty transported . . . and where their Negroes may continue to be useful to them.”[44] Samuel Bryan was listed among the returns of refugees in St. Augustine in 1783, his household consisting only of himself and a Black woman, presumably a slave.[45] His wife and nine children appear never to have made it to St. Augustine. The same appears to be true for Bryan’s officers, Lieutenant Colonel Hampton and Captain White, who are not named in any available documents from East Florida at this time.

British records indicate that almost 7,500 British troops, Loyalists, and other emigres (2,925 white and 4,448 blacks) arrived in East Florida in 1782. By 1783, the population of the province had grown to between 16,000 and 17,375 people.[46] By April of that year, news reached St. Augustine that East Florida was to be returned to Spain as part of the peace settlement. As might be expected, the news did not sit well with many who would now, if they chose to remain British subjects, have to uproot and relocate themselves yet again. One dejected St. Augustine resident noted that “should England be engaged in another war . . . let her not expect that, out of thousands of us Refugees, there will be one who will draw a Sword in her Cause.”[47] By August 1785 the evacuation of those choosing to leave was complete. Some 3,000 returned to the new United States, and another 4,000 to lands along the Mississippi River. Much smaller proportions of Loyalists went to Jamaica, Nova Scotia, the Bahamas, or England.[48]

Samuel Bryan was one of thousands of Loyalists who returned to the United States in the years following the Treaty of Paris. He and “several other obnoxious characters” arrived in Wilmington, North Carolina in early June 1783. Bryan and the other “fugitives” were referred to local judges who sought unsuccessfully to have them sent back to St. Augustine.[49]

While Samuel Bryan’s life was spared after his conviction for treason, his property was not. Two months after his trial, in May 1782, Bryan and dozens of other men were listed in a state law of those who were to have their land or property confiscated.[50] Later in 1782 some of Bryan’s land and slaves were confiscated and sold. In another instance of rather extreme irony, two Patriot officers who had previous connections to Bryan personally profited from the sale of his slaves and land. Major Lewis, who protected Bryan at the Salisbury jail, bought at least three of his slaves.[51] Gen. Griffith Rutherford, who pursued Bryan’s Loyalists in June 1780, received commissions on the sold land and slaves.[52] From available records, Bryan lost or was forced to sell 576 acres of land, reduced from 900 acres at the time of his conviction down to 324 acres in 1784.[53]

Samuel Bryan died in 1798 in Rowan County on the same land where he spent the better part of his life. That Bryan did not relocate to Kentucky to start a “new life” among his siblings is a testament to both his own character and that of his neighbors who appeared to have accepted him back into the community. By the time Bryan made his return in 1783, North Carolinians (or at least their legislature) were ready to legally reconcile with Loyalists. The Act of Pardon & Oblivion absolved most Loyalists from future persecution and punishment.[54] Interestingly, the Act exempted men like Bryan who had been British officers and those who spent more than a year outside the state with the enemy. Despite being exempted, there does not appear to be any further sanction against him from 1783 onward. Only two documents survive from the last fifteen years of his life: his will and a letter to a brother in Kentucky. Both documents bear a decidedly religious and almost penitent tone. An abundance of gratitude to the Almighty may have been in order after his wartime trials and other tribulations. Perhaps Col. Samuel Bryan, in one way, was aware of his relatively good fortune. He was able to return home, the same home he knew before the war, and was able to remain there relatively peacefully until the end of his life. Some or even most Loyalist refugees, who never returned or returned to America far afield from their original homes, may have preferred a similar fate.

The author would like to thank Todd Braisted for providing both insight and documentary sources on the North Carolina Volunteers and Royal North Carolina Regiment.

[1]Adelaide L. Fries, Records of the Moravians in North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton, 1922), 2:792.

[2]J.D. Bryan, The Boone-Bryan History (Frankfort, KY: Coyle Press, 1913), 13.

[3]Address of inhabitants of Rowan and Surry Counties to Josiah Martin concerning loyalty to Great Britain (no date, assumed to be sometime in 1775), William Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886-1907), 9:1160 (CRNC).

[4]Fries, Records of the Moravians, 3:1045.

[5]Commission to Appoint Allan MacDonald et al. as Officers of Loyalist Militias, Josiah Martin, January 10, 1776, in Saunders, CRNC, 10:441-443.

[6]Peter W. Coldham,American Migrations, 1765-1799: the lives, times, and families of colonial Americans who remained loyal to the British crown before, during, and after the Revolutionary War, as related in their own words and through their correspondence (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 2000), 612.

[7]Claim of Samuel Bryan, August 28, 1782, Great Britain, The National Archives, American Loyalist Claims, Audit Office, Class 13, Volume 117, folios 346.

[8]Robert O. Demond,The Loyalists in North Carolina during the Revolution (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1940), 103, 153-157.

[9]Jo Linn White, Rowan County North Carolina Tax Lists, 1757-1800 (Salisbury, NC: Privately Published, 1995), 181.

[10]Morgan Bryan oath of allegiance, August, 1778 and Morgan Bryan power of attorney statement, September, 1779, Bryan Family Papers, Shane Collection, Presbyterian Historical Society.

[11]Charles Cornwallis to Henry Clinton, July 14, 1780, Ian Saberton, ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War (East Sussex: Naval and Military Press, 2010), 1:168.

[12]Francis Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 4, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 1:192.

[13]Charles Stedman, A History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (London: Printed for the Author, 1794), 2:197.

[14]Vernon O. Stumpf, Josiah Martin: The Last Royal Governor of North Carolina (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press for the Kellenberger Historical Foundation, 1986), 188.

[15]Josiah Martin to Lord Germain, August 18, 1780, Walter Clark ed., State Records of North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886-1907), 15:55 (SRNC).

[16]Rawdon to Cornwallis, July 4, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 1:192.

[17]Claim of Andrew Hamm, February 17, 1787, American Loyalist Claims, AO 12/35/155, British National Archives.

[18]Cornwallis quoted in Caroline W. Troxler, “Before and After Ramsour’s Mill: Cornwallis’s Complaints and Historical Memory of Southern Backcountry Loyalists,” in Rebecca Brannon and Joseph S. Moore eds., The Consequences of Loyalism: Essays in Honor of Robert M. Calhoon (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2019), eBook, no page or location provided.

[19]Cornwallis to Cruger, September 4, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 2:178.

[20]Jim Piecuch, The Battle of Camden: A Documentary History (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2006), 147.

[22]Stedman, American War, 2:225-226.

[23]Cornwallis to Wemyss, August 28, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 2:208.

[24]Cornwallis to Leslie, June 3, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 5:163.

[25]Claims of James Hamilton, AO/13/119/419 and Roger Turner, T/50/5/58-59.

[26]Library and Archives Canada, Ward Chipman Papers, MG 23, D1, Series I, Volume 27, 335-336, 364.

[27]Salisbury District Criminal Action Papers, State Archives of North Carolina, DSCR 207.326.2.

[28]Acts of the North Carolina General Assembly, 1777, North Carolina General Assembly, April 7, 1777 – May 9, 1777, in SRNC, 14:10.

[29]Jethro Rumple, A History of Rowan County, North Carolina Containing Sketches of Prominent Families and Distinguished Men with an Appendix (Salisbury, NC: J.J. Bruner, 1881), 236-237.

[30]Blackwell P. Robinson, The Revolutionary War Sketches of William R. Davie (Raleigh, NC: Department of Cultural Resources, 1976), 51.

[31]John V. Orth, “The Strange Career of the Common Law in North Carolina,” Adelaide Law Review, 2015, 24-25.

[32]Richard Henderson, William Richardson Davie, and John Kinchen to Thomas Burke, March 28, 1782, SRNC, 16:523.

[33]Judiciary Report of Samuel Spencer and Jonathan Williams, April 5, 1782, SRNC, 16:269.

[34]Thomas Burke to Rowan County Sheriffs, April 6, 1782, SRNC, 16:270.

[35]Pension application of Andrew Carnahan (W8577), National Archives and Records Administration.

[36]Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. Thomas Burke from Alexander Leslie, April 10, 1782, New York Public Library Digital Collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c02c9a3b-6707-7080-e040-e00a180631aa.

[37]Alexander Martin to Nathanael Greene, May 12, 1782, Richard K. Showman, ed., et. al., The Papers of Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill, NC: Published for the Rhode Island Historical Society [by] University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 11:185-186.

[38]Greene to Martin, July 1, 1782,Papers of Nathanael Greene, 11:386.

[39]Julie Murtie Clark, Loyalists in the Southern Campaign of the Revolutionary War (Baltimore. MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1981), 1:361-362.

[40]Todd Braisted, “An Introduction to North Carolina Loyalist Units,” The Online Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies,www.royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/ncindcoy/ncintro.htm.

[41]Alexander R. Stoesen, “The British Occupation of Charleston, 1780-1782,”The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Volume 63, No. 2(April 1962), 81.

[42]Joseph W. Barnwell, “The Evacuation of Charleston by the British in 1782,” The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, 1910, 26.

[43]Bryan Claim, AO/13/117/346.

[44]Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), Kindle Edition, location 1095.

[45]Lawrence H. Feldman, Colonization and Conquest: British Florida in the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 2007), 29.

[46]Linda K. Williams, “East Florida as a Loyalist Haven.” The Florida Historical Quarterly,54, no. 4 (1976), 473.

[49]Letter from Archibald Maclaine to George Hooper, June 12, 1783, SRNC, 16:965-967.

[50]Acts of the North Carolina General Assembly, 1782, SRNC, 24:424.

[51]A.B. Pruitt, Abstracts of Sales of Confiscated Loyalist Land and Property in North Carolina (Rocky Mount, NC: 1989), 5.

[53]Ibid, 200. & Linn, Rowan County North Carolina Tax Lists, 223.

6 Comments

You have tracked down a lot of obscure sources—good work!

John, your comment is much appreciated. The research for this article occurred (in starts and stops) over the period of three years. There is no way this research happens without superb university libraries nearby (central NC) as well as easy access to the state library/ archives in Raleigh.

This is the most thorough and informative work on Samuel Bryan I’ve ever read, and I appreciate your sharing it with those of us who are fascinated by the patriot and loyalist commanders who were native to Piedmont North Carolina. It seems you’re correct in highlighting Bryan’s trial for treason, which eventually reflected a spirit of postwar reconciliation in the state, as more noteworthy than his military service, which appears to have been rather ineffective. That clarifies my own perspective about Bryan. Your footnote #10 suggests that the Bryan family were Scots-Irish Presbyterians like so many others who migrated from Pennsylvania to Piedmont NC? Is there further evidence of a Presbyterian connection?

George, thank you for the very kind note. I did not find any Scots-Irish and/ or Presbyterian lineage with the Bryan family. Samuel’s mother’s maiden name was Strode. There are a few indications that the Bryans, before Samuel’s time, (along with the Boone family) were Quakers.

The Bryans never indicated Quaker connection here in what is now Davie County on the Yadkin River. They were friends with the Moravians missionaries from Salem on the other side of the river and where they traded with them but all surviving evidence suggests they were heavily involved in the earliest Baptist church west of the Yadkin River called Timber Ridge. We have documents supporting this and the Bryan family in the Davie County archives at the Davie County Public Library History Room and I wrote of it in a recently published by The History Press book called Historic Shallow Ford in Yadkin Valley (available by going to http://www.marciadphillips.com. Samuel Bryan eventually returned to end his life among family and friends.

Marcia, to clarify I did not state the Bryans, as situated in then Rowan country, were Quakers. Looking back into the family history from the available sources before they arrived in North Carolina, there were some indications the family had, or were associated, with Quakerism. Again, this was prior to their arrival in North Carolina. So I do agree that there appears to be no sources linking Samuel, specifically, to Quakerism.