As night slowly gives into morning the salty breeze brings a mist across the suffocating sulphury air filled with fireballs. The fireballs pass each other in the sky like defined lanes of a road. Crashing into mounds of dirt. Ripping through structures of the small town. Igniting infernos and filling the air with choking smoke, that some risk breathing for the safety of its cover. Welcome to Yorktown, Virginia, October 16, 1781.

Now the British guns fall silent[1], while the Allied cannon continue to roar without answer. Emerging from the massive redoubt known as “The Hornwork,” soldiers steadily move to their objective just across the field, where the machines sponsoring their suffering and death for the last few days sit idle and only slightly warm. The defenders not taking part in the sortie are peeking over and between the long earthen walls as this dramatic moment unfolds. An officer with years of experience in North America, Col. Robert Abercrombie, rushes his confident soldiers over freshly dug but unfinished works[2] connecting American and French lines, bayoneting their way to the guns.[3] Discovering they have brought along the wrong tools for the job, which is to spike the cannons and render them useless, they proceed to thrust their bayonets into the touch holes and shatter them off.[4] The American and French forces quickly gather themselves to a response, the British are forced to retire; Hessian Jäger Capt. Johann Ewald listens to accounts from those returning, and scribbles a few lines into his journal.

Several weeks before these events the British and their Hessian auxiliaries poured into the port city of Yorktown, Virginia, after a long campaign, to await evacuation. Captain Ewald led a small elite group of green coated light infantry called Jägers.[5] Thanks to the post-World War Two work of Joseph P. Tustin, who hunted down the volumes of Ewald’s diary, we have been passed an important text opening a window into the American Revolution’s front-line soldiering, and a valuable narrative to modern battlefield walking. Captain Ewald’s writing makes for an interesting day walking the fields of Yorktown National Battlefield and neighboring Gloucester, as he himself “toured” the location in far more depth than many modern visitors today. Captain Ewald’s footsteps at Yorktown covered today’s modern Colonial Parkway from Williamsburg, over to Gloucester, Yorktown itself, the main British defenses, and even a post-surrender peek at the American and French works. A remarkable journey that left us a well-detailed view of the last major action of the American Revolution.

Marching through Virginia in the fall of 1781, Captain Ewald described the footsore army as “baggage” heavy, similar to a “wandering Arabian or Tartar horde,” a fine visual for modern visitors to grasp the movement of eighteenth century armies. Perhaps a welcomed change as the men passed through Sarah Creek to the higher ground on Gloucester Point was the arrival of fall weather. For weeks the unbearable summer heat soaked their uniforms with sticky perspiration, various biting insects had left their marks, and few nights provided relief as the southern climate offered no forgiveness for the exerted.[6] Not much today remains of these positions on the Gloucester side; in fact many visitors simply skip the location. To those who make the trip the remnants do provide a reasonable visual into the Gloucester defenses. On the left flank of Ewald’s position, at Tyndall’s Point Park, is remnants of American Civil War trenches that give the visitor a general idea of how the King’s army fortified the location to hold off any Allied advance.

On August 1, Ewald and his men arrived in his position during a violent whirling thunderstorm[7] that sent a few boats hurling towards the shore and away from their destinations. Later in the siege, British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis’s attempt to escape to this location would be impacted by another such storm. It is likely Ewald recalled the events of this storm when he developed his conclusion that the later escape plan was doomed.[8]

As the Jägers settled into their defenses they began the work of intelligence gathering and foraging. Towards the end of the month light skirmishing took place in several of the forward positions,[9]but the more pressing matter was the rumors.

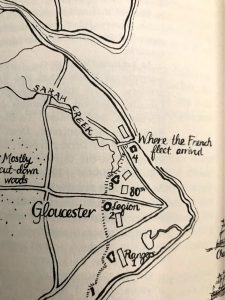

Ewald began to hear that George Washington and French troops were headed to Virginia.[10] Many of the rumors were dismissed in such a way that, even if true, the Allied army could not contend with the British fleet and certainly could not stand toe-to-toe with Gen. Sir Henry Clinton’s army, which was soon to arrive. The confidence of the men serving in the King’s army stemmed from past success and further exploits throughout the year of 1781, which included large masses of soldiers boarding warships,[11] a feat the Continental Army simply could not match. Had the fleet with Clinton arrived in time, it may well have spelled disaster for the Allies. One of the keys to visiting the beachfront areas of both Gloucester and Yorktown locations is to get a feel for the daily view often taken by the King’s soldiers while awaiting evacuation. It was this constant peering out into the river that became a daily distraction, watching a few British ships come in, drop anchor and then go out. It likely presented a feeling of security for the men in this holding pattern for what they believed was just a short time longer. That all came to an end when Ewald entered in his journal on August 30, “distant smoke of a cannonading which seemed to be drawing ever nearer.” Sometime later he continued “I could detect three heavy vessels in the distance.”[12] Noticing the white flags, Ewald knew the French Navy had arrived and were now blocking the mouth of the York

River.

The relatively quiet encampment now appeared to be transitioning into a siege defense. The lackluster approach to setting up a post to simply await evacuation, or as Ewald described the time leading up to the French fleet’s arrival “Negligence and laziness,” now moved to the feverish scarring of the land as a proper defense began to take shape. As days passed, heat, illnesses and an overall feeling of desperation began to set in for Ewald and his men as confidence in a defeat of the French Navy dwindled to no longer being a possibility. Passing the beach area, Ewald joined a friendly naval officer in an elaborate plan to send fire ships towards the French blocking forces at the river mouth.[13] The illumination from the flaming crafts lit up the French forces to onlookers, but the French easily navigated away as the fire ships burned out and sank.[14] A unique effort had failed.

From the time of the failed fire ship plan, Ewald and his Jägers fought pointed engagements and light skirmishes across the Gloucester point. A drive from Tyndall’s Point Park to the modern City of Gloucester loosely follows his various missions. Fighting in woodlots, mostly abandoned plantations and entrenched works, one thing became clear: the situation was getting worse on the Gloucester side. On October 9, Ewald crossed the river to the Yorktown defenses to observe the works and deliver reports to Lord Cornwallis.[15]

What he found was further signs of a potential defeat. Ewald arrived in time to see one, if not the first, cannonballs from the opening of the siege smash into the town and defenses throwing flame, smoke, and debris into the air.[16] From this point forward the skies remained a traffic jam of flaming hot fireballs and explosive destruction. An unending cacophony of noise with gruesome visible injuries replaced hope with fear as the day-to-day life of selfless service in the works gave way to selfish thoughts of individual survival. An example of this is occurred on October 11, when the Hessian camp, just behind the Customs House, faced a severe bombardment injuring many soldiers who were taking a respite from post duty.[17] After this notable event, Hessian soldiers began deserting, likely to the right of their camp location and out of the communication trenches beyond.

Ewald and his Jägers would find themselves in multiple precarious positions as the days passed. The Jägers’ mission expanded to make up for losses elsewhere, such as manning trenches, fighting off bayonet attacks and even finding themselves responsible for an artillery battery.[18] The experiences he endured on the Gloucester side and his early ability to map the area may have led to many of his conclusions that an escape plan from that side was unlikely to be successful.

October 16 and 17, 1781, offered the last-chance efforts of a besieged army. Facing continued bombardment, bayonet storming, wounds and illnesses was so debilitating that even the slightest mention of hope for a rescue seemed to “irritate” Captain Ewald.[19] While he viewed Lord Cornwallis as an honorable man, he took no consideration in the commander’s final plans to break out of the predicament by way of Gloucester. Standing by the water near his battered trenches, Ewald looked at the deteriorating conditions of the works as the sound of the Allied guns announced the results of Colonel Abercrombie’s efforts. It had failed. Later in the evening, Lord Cornwallis tried to move his exhausted and battered men across the river to the Gloucester works in an attempt to launch a breakout, but a violent thunderstorm prevented the mission’s success.[20]

On the other side of the field, American Surgeon James Thatcher wrote of what Ewald was observing on his side of the field. “The whole peninsula trembles under the incessant thunderings of our infernal machines, we have leveled some of their works in ruins and silenced their guns; they have almost ceased firing.” With a surgeon’s eye he went on to capture the sights that Ewald saw going to and from the defenses, “men in their lines torn to pieces by the bursting of our shells.”[21] As the sun rose on the 17th, Ewald and his men entered the battered and smoking Hornwork. Ewald wrote, “One saw nothing but bombs and balls raining on our whole side.”[22]

Later that morning, a single British drummer ascended the Hornwork and beat a parley. Drowned out by the cannonade, the misery of the firing continued until finally someone from the Allied lines spotted the anomaly. As the cannon fire paused, a British officer waving a white handkerchief crossed the lines with the drummer and delivered the request to negotiate terms of capitulation.[23]

On October 19, 1781, almost the exact date he arrived in the colonies five years prior, Ewald and his men marched down today’s modern Surrender Road to lay down their arms and officially end the defense of the posts at York and Gloucester. Days after, Ewald found himself mingling with some of the major personalities from the Allied army including George Washington and Comte de Rochambeau. Capt. Johann Ewald may not have known at the time he penned such memories, but he provided us with one of the first complete “tour guides” of the Yorktown Campaign. His work lives on within hundreds of citations throughout many publications.

Tench Tilghman traveled to pass the news to Congress of the Allied victory at Yorktown. Lord George Germain passed the news to Lord North of the British defeat.[24] Historians would work tirelessly over the years to pass the narratives down to each generation, narratives of people from all over the world, serving in a war that turned that world upside down, narratives that help define and digest the subsequent scholarly study and archeological achievements.

At Yorktown today the guns are silent, the scars upon the land well landscaped, paved paths take us to many of the key places, and wayside exhibits tell us a little about what happened here. The comforts of modern life and development blanket over a lot of the places Captain Ewald described. Places where he recorded his experiences and felt certain emotions have been lost over time, but one can still locate many areas he left his mark upon. The real value in his diary is to help enhance the Auto Tour, to go from the simple what-happened-here to the in-depth what-did-they-experience-here. To walk along the siege lines and look out over the fields and imagine Captain Ewald passing his wounded comrades, smoking structures, trenches filled with discarded and broken equipment, is to truly understand this moment in the American Revolution.

While modern battlefield walking gives visitors a look into the past, it is the diaries and narratives left behind that help bring these climactic moments into the present. At the opening of Ewald’s Diary is a quote from Boileau: “Honor is like an island, Steep and without shore: They who once leave, Can never return.” No better quote could illustrate the test faced by those who served in the Siege of Yorktown. How we recall them and pass the narratives to each generation is unique to us all, but the story always starts in the footsteps of those like Capt. Johann Ewald.

[1]Jerome A. Greene, The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781 (New York: Savas Beatie LLC, 2005), 261.

[2]James Thatcher, Military Journal, During The American Revolutionary War From 1776 To 1783 (Hartford, CT: Silas Andrus & Son, 1854), 277.

[3]Greene, The Guns of Independence, 261.

[5]David Ross, The Hessian Jäger Corps in New York and Pennsylvania 1776-1777 (Journal of the American Revolution, 2015) allthingsliberty.com/2015/05/the-hessian-Jägerkorps-in-new-york-and-pennsylvania-1776-1777/.

[6]Captain Johann Ewald, Dairy of the American War: A Hessian Journal, trans. Joseph P. Tustin (New Heaven: Yale University Press, 1979), 305, 314.

[11]Don N. Hagist, Noble Volunteers: the British Soldiers who Fought the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2020), 95.

[16]Ibid.; Thomas J. Fleming, Beat the Last Drum (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 1963), 243.

[17]Johann Döhla, A Hessian Diary of the American Revolution (Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1913), 168.

[21]Robert L Tonsetic, 1781: The Decisive Year of the Revolutionary War (Havertown PA: Casemate, 2013), 197-198.

[23]Fleming, Beat the Last Drum, 309-10.

[24]Richard M. Ketchum, Victory at Yorktown: The Campaign that Won the Revolution (Henry Holt and Co., 2004) 269-274.

6 Comments

Jason, Thanks, Well done! Ewald seems to have been everywhere. Esp. interesting at Cooch’s Bridge and Bound Brook NJ. even stayed here after the war. Bob Mayers

Thank you very much for this interesting tour! Great information, and the photos add a depth of understanding regarding locations. I will definitely be using this article next time I visit Yorktown!

Really enjoyed this. I love nearby and have a Hessian ancestor and look forward to visiting.

I have Ewald’s book and found it fascinating. I have read it twice now and won’t loan it out.

We went to Charleston and visited the plantations by the Stono River where the army crossed over to begin the siege of the City. I am sure that there are dead British and Germans buried in what they call the “slave cemetery” at Drayton Hall. It was an existing cemetery on ground where the British made their headquarters and established a hospital.

It’s remarkable that Ewald’s story was found and preserved. His grave was bombed in WW2.

“This great misfortunate, which surely caused the utter loss of the thirteen splendid provinces of the Crown of England, was due partly to the extension of the cordon, partly to the fault of Colonel Donop, who was led by the nose to Mount Holly by Colonel Griffin and detained there by love….Thus the fate of entire kingdoms often depends upon a few blockheads and irresolute men.” – Captain Johann Ewald, summing up the events between December 21-26, 1776 in Burlington County, New Jersey.

Ewald was a most astute observer, not only of battles but of human nature as well.