The British evacuation of Philadelphia had been under way for several days. Given the honor to be among the last units to leave, the Brigade of Guards slept on their arms by the redoubts north of the city the night of June 17. At daybreak, they embarked on flatboats to cross the Delaware into New Jersey, under the powerful guns of the floating battery Vigilant, which had played a central role in reducing Fort Mifflin to rubble the previous October.[1]

But the Honourable Cosmo Gordon, lieutenant colonel of the Guards’ 1st Battalion, a privileged bon vivant, spent the night in comfortable quarters, sleeping so late the next morning that the family whose home he occupied “thought it but kind to waken him, and tell him ‘his friends, the rebels’ were in town.” Scrambling to find one of the last boats to ferry him across, Gordon and his servant barely escaped American patrols probing the abandoned streets for stragglers.[2]

Over the years, Gordon has attracted considerable attention as a figure of romance.[3] A charge of murder and the records of three court trials paint an intriguing picture of the man’s character, while also revealing details of the Battle of Springfield, on June 23, 1780.

Cosmo Gordon was born about 1737, the fourth son of William Gordon, 2nd Earl of Aberdeen. From a powerful Scots family, Cosmo was doubly a Gordon. His mother, Lady Anne, was the daughter of Gen. Alexander Gordon, 2nd Duke of Gordon, who had served Prince James Stewart during the Jacobite Rebellion. Though unlikely to inherit his father’s title, as the younger son of an Earl, he was entitled to use the courtesy prefix, The Honourable. And use it he did, throughout his life.[4]

While studying in Brussels, around 1754, he was said to be “a remarkable well behaved young gentleman . . . very much connected in the most respectable families.” In 1759, at considerable cost, he purchased a prestigious commission in the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards, known as the Scots Guards. Because Guards regiments were household troops, nominally led by the King, they used a double ranking system, underlining their elite status—Gordon began his service as a lieutenant (often called a subaltern) in the Guards, but also held a higher rank, that of captain, in the army. He purchased a company in 1773, and was promoted to captain and lieutenant colonel, having already served nearly fourteen years as a subaltern. His portrait, thought to have been painted about 1770, shows him wearing the uniform of a grenadier officer.[5]

When the American war broke out, a composite corps of 1,100 men was formed from the Guards, merging soldiers from all three of its regiments into a brigade of two battalions, with five companies in each. Sent to the colonies, the brigade arrived off New York in July 1776, in time for service at the Battle of Long Island the next month. When Gordon joined the Brigade of Guards at its winter quarters in Philadelphia in 1778, he was placed in command of the 2nd Company of the 1st Battalion.[6]

As the British army retreated across the Jersies toward New York, Gordon’s company saw action at the Battle of Monmouth. Advancing toward an American battery, the Guards were ambushed from a patch of woods, receiving a volley into their right flank at twenty yards that mowed down several guardsmen at close range. The Guards wheeled right, fired a volley and charged with the bayonet, clearing the woods in a vicious hand to hand struggle. Their battalion commander, Henry Trelawny, was shot down, and Sir John Wrottesley, leading the 1st Company, was also wounded. Gordon, in a couple of close calls, “had his bayonet shot off from his fusee; and afterwards by a rifleman in the wood, was shot through his coat under his left breast, without hurt to his side or arm.”[7]

By 1780, he commanded the 1st Battalion. There seems to have been a simmering dislike of Gordon among the junior officers, a predisposition to find fault with the well connected aristocrat. As subsequent events showed, it seems probable that Gordon’s immediate subordinates chafed under his command, and would enjoy bringing him down a peg. Their evident dislike and clear disloyalty does not speak well of Gordon’s character as a leader of men, and Gordon himself seems to have avoided the company of his subordinates.

Commanding the 1st Company under Gordon was thirty-five-year-old Welshman Lt. Col. Frederick Thomas, who had purchased his company the previous December. His father had served as Treasurer to Augusta, mother of King George III, and his uncle was a British general. Despite his recent promotion, Frederick’s status as a member of the minor nobility left him several ranks below that of his commander, and it is likely that Gordon’s snobbish treatment offended his younger subordinate.[8]

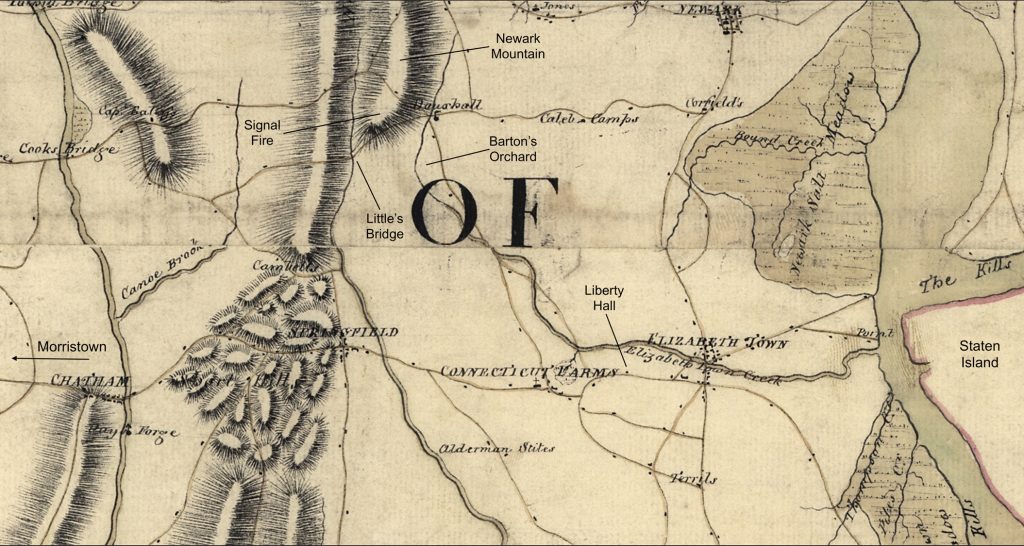

In the Spring of 1780, the troubled Continental Army kept post behind the Watchung Mountains at Morristown, New Jersey, keeping an eye on the British occupying Manhattan, thirty miles to the east. Strategically, the position was a good one, with access to the Hudson valley and West Point, fifty miles north, as well as to the capital at Philadelphia, seventy miles south. From there Washington could contest British access to food and forage. Fourteen miles southeast of Morristown, at the base of the Short Hills, sat the village of Springfield, controlling the passes toward Morristown.

Sir Henry Clinton had captured Charleston on May 12, the news reaching New York on the 28th, and Washington’s headquarters shortly after. On June 7, awaiting Clinton’s return with his army, Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen launched a halfhearted probe toward the American encampment. Logistical problems and a spirited American defense bogged down his force at Connecticut Farms (present-day Union); in retaliation, frustrated British and Hessian troops set the town afire before retiring.[9]

When Clinton returned from Charleston, Washington anticipated a British thrust up the Hudson toward West Point and began moving troops north on June 20, leaving Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene to guard Springfield. Learning that the Americans had divided their army, Clinton ordered Knyphausen to conduct a second probe on June 23, aimed at capturing the army’s “public stores.” This time the German split his force into two prongs, hoping to pin the rebels in place at the town of Springfield with the main body, while sending Maj. Gen. Edward Mathew to turn their northern flank. Loyalists spearheaded the flanking detachment, followed closely by the Brigade of Guards, the column’s main punch. But, worn down by the long dragging war, the British were not at their punchiest, as will be seen.[10]

Lt. Col. Gordon and his men stepped off early, leaving their Elizabethtown camp by three o’clock in the morning. They soon came to Liberty Hall, the home of William Livingston, where the Americans usually kept an outpost. Seeing no opposition as they approached, Gordon “proposed to Col. Norton to canter on in front to see the ladies at the Rebel Governor’s house . . . after five minutes conversation, and having received what intelligence he wished to have, they made their bow, and rejoined the column that was then passing nearly opposite.” Concerned that her home would be burned, the governor’s daughter Susan requested Gordon’s protection, to which he agreed, posting a guard at the property. He received a rose from the young lady for his gallantry, and placed it conspicuously in his hat, probably breeding resentment and jealousy among the troops and junior officers slogging by.[11]

Shortly afterward, they encountered resistance near Connecticut Farms. The Queen’s Rangers chased the American advance guard back over the bridge into Springfield, where the a larger American force was posted. As the British troops rested, American artillery began firing on them. Gordon was sitting on a fence when a cannon ball came very near him, and a fellow Guards officer “told him he had better take the flowers out of his hat, for he thought the Rebels aimed at him.” Given the distance, Gordon’s roses couldn’t have been much of a mark; the comment was likely made in jest. But the hazard was genuine. Another shot from the gun killed two Queen’s Rangers resting nearby. Though witnesses reported him unfazed, perhaps this close call rattled Gordon.[12]

From Connecticut Farms, Mathew’s column headed north to circle the Springfield position. Approaching Vauxhall, the British received enfilading fire from Americans posted near an orchard a quarter mile to their left. Lt. Col. Joseph Barton’s 1st Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers deployed to dislodge the American skirmishers, but without success. Lt. Col. John Howard, commanding the Guards, halted the march and sent Frederick Thomas’s lead company to support Barton, soon followed by a second Guards company under Capt. Frederick Maitland. The enemy proving resistant, the guns attached to the Guards were brought into action under Lt. Augustus O’Hara. Gordon joined O’Hara and attempted to direct the firing, but, within his right, the plucky artillerist ignored him, continuing to aim the guns himself.

Here matters took an ugly, personal turn, accentuating how the fog of war made it difficult for participants to know exactly what was taking place on the battlefield, where witnesses “are too much engaged with their own particular duty, to attend to the situation of others.” Having chased the Americans, Thomas sent a noncommissioned officer after his battalion commander for orders, probably suspecting that Gordon would not be easily found. Before that messenger could return, he impatiently sent another and possibly a third in search of Gordon. Thomas later argued he just wanted to clarify the situation, expressing surprise that Gordon was not where he ought to have been. Gordon, however, suspected Thomas of “a settled pre-determination to find something in my conduct, which might be a subject for future censure.” Though Thomas later protested he held “no private pique against Lt. Col. Gordon,” his very mention of the idea suggests that this was indeed on his mind, and Gordon likely sensed this at the time.

The British crossed the Vauxhall Bridge, then turned west where the road ran beneath the point of Newark Mountain. A signal fire had been ignited atop the ridge that morning to alert the militia, which now skirmished from its wooded slope, pouring fire into the right of the passing column. Continentals gave ground before the oncoming force, forming on a rise beyond Little’s Bridge, which spanned the Rahway River, leaving a small force of skirmishers to contest the crossing.

At this point, Mathew’s force suffered a breakdown of good order, symptomatic of the army’s growing frustration and increasingly slovenly prosecution of the American war. The Queen’s Rangers swarmed across the fordable Rahway near the bridge, but in chasing the enemy zealously, veered too far to the right, away from Springfield. When a guide assigned to the rangers requested they pull back toward the road, their commander, Col. John Graves Simcoe, refused, saying such orders must come from General Mathew. The guide hastened back to Mathew, who was flustered at finding no aides nearby. Currying favor, Lieutenant Colonel Howard, commander of the Brigade of Guards, eagerly volunteered to carry the message personally to Simcoe. Rushing off like a tyro, he failed to explicitly delegate command to his next in line, Cosmo Gordon, who was hanging about the general’s party.

Harboring resentment toward Gordon, the junior officers in both battalions were ready to ignore and undermine his authority. They may have been giving him the cold shoulder throughout the march, motivating the colonel to spend time with officers more to his liking. Receiving no specific orders, they chose to pretend he was not in command.

Meanwhile, the Guards faced resistance from “the heights of Springfield” to their front. Knowing they needed to seize the ridge ahead to keep their casualties down, several officers simultaneously ordered the brigade to charge the high ground. Gordon claimed he gave the order from the rear of the brigade; Lt. Col. Hon. James Stewart, commanding the third company in line, said he gave the order and worried about the consequences of overstepping. Frederick Thomas, with his company at the head of the column, also claimed to have led the Brigade to the heights. The six companies pelted uphill by divisions, one after the other, grabbing the crest as their opponents backpedaled toward Hobart’s Gap, the main pass through the Watchungs to Morristown.

Blown from the rapid climb in the midday heat, the Guards lay on their arms atop the rise, recovering their breath. Gordon stated that he gave the order to rest, but his peers said they did not notice him when they reached the top. Rather than credit Gordon for commanding, his fellow officers contended that taking the heights and resting after the uphill run were simply spontaneous actions on the part of the troops.

For his part, Thomas was irate by the time he finally encountered Gordon on the heights. Losing composure, he attacked his superior angrily. “Col. Thomas was in a great passion, and when in that situation speaks thick; but one of the expressions was, where have you been skulking? I have sent every where for orders, but could not find you.” Affecting nonchalance, Gordon replied coolly that “he had been waiting in the rear for orders.”

Once roused, the hot-headed Thomas could not leave the matter alone. He tried embarrassing Gordon before his superior: “Col. Howard, I have had the honor to command the brigade of Guards today.” Gordon’s mocking response, “If that is a feather in your cap, Sir, you might wear it” must have further enraged Thomas, especially considering the jaunty flowers in his own hat. Incensed, the Welshman continued to rant to anyone who might listen, causing Howard to caution him, “that if he spoke so loud, Col. Gordon would hear what he said, and Lieut. Col. Thomas answered that he meant he should.”

Thomas continued to rag Gordon, speaking “in a hurry, and with warmth.” While this conduct was insubordinate, Howard felt the individuals involved needed to reach a personal understanding. He “thought it must come to a further explanation when they arrived in camp.” The gentleman’s code of honor required either an apology or a challenge to duel.

General Knyphausen heard the increased firing to the north and pushed his men forward into Springfield. The undisciplined troops vented their frustration at the harassing, annoying enemy by torching the town. Mathews’ men turned south toward the conflagration, having failed to close the trap. The urgency now reduced, they paused for lunch, the officers sheltering in a shady hollow. Gordon observed an enemy column approach their position, dragging a couple of cannon, and asked Howard if he could alter the facing of some of the companies whose position was exposed. Somewhat reluctantly, Howard agreed, the officers making light of the threat despite a couple of rounds being fired by the guns. Abetting Thomas’s harangue against their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart quipped, “he means to show you he can be active.”

Unable to come to grips with the enemy on advantageous terms, Knyphausen retired toward Elizabethtown; the Guards, followed by the Queen’s Rangers, bringing up the rear. The Rangers fended off the enemy, who continued to harry them all the way. Thomas’s railing persisted on the return march. Frustrated by Gordon’s composed responses and seeming indifference, he was further galled when the target of his ire acquired yet another mark of distinction. As the retreating brigade again passed Liberty Hall, scene of Gordon’s early morning gallantry, a shot rang out from the vicinity of the house, wounding the Scot in the upper thigh. It may have been a nearly spent ball, fired from a distance, because it did not penetrate, but it caused a serious contusion, which was examined by the Guards’ surgeon, Dr. John Rush.[13]

Gordon went on to New York to convalesce in the city. Guards officers who had been eager to see the dispute with Thomas “come to an explanation” were now faced with a five week delay, as the aristocrat recovered in relative comfort. Far from the humiliation Thomas had desired, his commander now became the hero of the Springfield affair. While recuperating, Gordon’s double honor of a rose and a wound was the topic of much conversation among the ladies, generating a lively public controversy between female correspondents in the local newspapers.

On June 29, a letter in James Rivington’s Royal Gazette, a Tory publication read avidly by British officers, chided the ungrateful Whigs for shooting the man who had protected Livingston’s home in front of that very house. A Whig rejoinder in The New Jersey Journal argued that it was all a mistake and Gordon had not been shot. Yet a third letter reaffirmed Gordon’s wound, noting that he “brags of the Lady’s Favour!—Received on horse-back,” and that he felt himself “honored by the sign manual of the fair Clarinda! It is whispered that on return from the excursion, notwithstanding he wore the sweet present next his left breast, the afternoon he received an other, in the vicinity of Mr. William L – – -’s house, tho’ also very honourable, not near so agreeable as that he had the pleasure to receive at 4 o’clock that morning.”[14]

In camp, Thomas would not stop complaining about Gordon, provoking the junior officers to draft a circular to “send him to Coventry”—they would refuse to communicate with Gordon except in the line of duty. This subversion of order so worried the brigade major, Thomas Collins, that when Gordon returned to duty, he informed him that officers were talking behind his back. Believing Thomas was undermining his authority, Gordon confronted him publicly, placing his subordinate under arrest and humiliating him by taking his sword. A court martial followed; the charge: “secretly and scandalously aspersing Gordon’s character, in a manner unlike an Officer and a Gentleman, during his absence from his command.”[15]

General Clinton authorized the trial by noting that it was needed to decide on a “difference” that had arisen between the two men. This important distinction between matters of duty and a gentlemen’s dispute was something Thomas failed to appreciate fully. Thomas felt his accusations were of such import that the army should take up his cause and punish Gordon. Yet he never formally lodged any charges. Howard, Gordon’s commanding officer, was asked “Does he think what Thomas said was of import to the disservice of His Majesty’s arms?” He replied that he “cannot answer such a question,” noting that “he had no regular complaint made to him.” When army regulation conflicted with the culture of the British officer corps, culture was sure to prevail. By serving as their spokesman Thomas attempted to crystallize the junior officers’ dislike of Gordon into institutional action. Instead, he found himself hung out to dry by the brass, who preferred maintaining solidarity of command to countenancing insubordinate behavior over minor matters. Dissatisfied subordinates frequently brought similar charges. Encouraging this threatened both their authority and the greater good of military order.

Because the matter was viewed as a private affair between gentlemen, the court found Thomas not guilty. They accepted Thomas’s defense. The charge had been formed improperly—he had never aspersed Gordon’s character secretly, but rather had done so publicly and often. If anyone hoped the verdict would end the matter, they were mistaken.

Ten days after the Thomas’s acquittal, Gordon encountered him on the streets of New York wearing his sword and challenged him to a duel. Refusing to accept personal responsibility for his actions according to the unwritten code of gentlemanly conduct, Thomas declined the meeting, protesting that the matter was still “depending and undetermined.” He “accompanied that answer with positive orders to his servant, to receive no letters of any kind” from Gordon.[16]

His character besmirched, the accusations rankling, Gordon demanded his own court martial to vindicate his honor. Unable to dissuade him, a board of general officers at New York recommended that a trial be held, which, having been approved in London by Sir Charles Gould, the Judge Advocate General, was finally held during August and September 1782.[17]

Thomas returned to London in November 1782; Gordon, the following June. The aggrieved Gordon soon sent a letter to his antagonist written “in the ordinary terms of persons who conceived their honour was injured, and demanding peremptory satisfaction.” Thomas again declined to meet him, stating insolently that he was prepared to defend himself:“Sir, I have received your challenge, which as I am not a fool or a mad man, I shall not accept at this late hour . . . do not deceive yourself, for as I have acted hitherto with firmness and propriety, I do not mean now to lay them aside, and be assured the man who dares to attack me, shall find me inclined, and perfectly able to make use of my sword, as he who dares insult me, shall abide by the consequence.”[18]

He again ordered his servant, Thomas Hobbs, to refuse all letters from Gordon, then repaired to the country for the summer. But immediately on returning in September, he was waited on by a fellow officer, Maj. Francis Skelly, Gordon’s cousin, who delivered a third challenge: “I am now Sir, under the necessity of acquainting you, that you must either resolve to meet me at six to-morrow morning with pistols, at the ring at Hyde Park, in company with a friend; or submit to be held up to the world in a most dishonourable light.”[19]

Thomas reluctantly agreed, sought the assistance of a second, who procured two brace of pistols, then wrote his will, protesting: “I am now called upon, and, by the rules of what is called honour, forced into personal interview with Colonel Cosmo Gordon. God only can know the event, and into his hands I commit my soul, conscious only of having done my duty.”[20]

Next morning, as Hobbs watched from a nearby garret, Thomas, wearing his regimental uniform and accompanied by his second, Guards Capt. John Hill, exchanged shots with his nemesis. The pair advanced to eight paces and fired. When Thomas’s pistol flashed in the pan, Gordon asked the seconds if that should count as Thomas’s shot. The gentlemen overruled him and Thomas fired a second time, missing. “after this they took other pistols and fired again, the pistol ball of [Thomas] struck [Gordon] somewhere on the right side, but did not penetrate his body, unfortunately the pistol shot of the prisoner struck [Thomas], and penetrated into his bowels, he fell with the wound.”

Gordon asked his surgeon, Alexander Grant, to attend “the poor man,” but the wound was mortal. Thomas was carried back to his house, where he expired still railing against Gordon—“that villain! that villain!”

Dueling being illegal, Gordon fled to Calais, where he was seen at the Hôtel d’Angleterre, the pain of his wound causing him to limp about the garden with a stick. He returned to England the next year to face trial on a charge of murder. The prosecutor took pains to paint Gordon as aggrieved and Thomas as obstinately persisting in an error. Like the judge advocate in Gordon’s court martial, he wanted no responsibility for impugning the character of a noteworthy and potentially dangerous man: “I feel what every man who hears me must feel, that the strict and rigid rules of law, applied to the subject of deliberate duelling, is in direct opposition to the feelings of mankind, and the prevailing manners of the present time: be the rule of law what it may, in defiance of that rule, men do find it justifiable, commendable, and necessary, to risk what is called in one of these letters,”The decision of their differences,” before a tribunal which they erect for themselves.”[21]

To be on the safe side, Gordon called an impressive list of witnesses to testify to his quiet and peaceable character. Sir Henry Clinton, Lord Dunmore, Gen. James Paterson and Adm. Mariot Arbuthnot led the procession. From its outset, the trial’s tone was perfunctory; the conclusion foregone: the jury deliberated ten minutes and Gordon was acquitted. The following month, Gordon sold his commission and quit the army.[22]

He continued to live the life of a cultured gentleman, spending time in Italy, attending the races at Ascot, and subscribing to the Harmonic Society in the City of Bath. On February 27, 1813, The Honourable Cosmo Gordon died at Bath where he was buried. Unmarried and childless, he left his estate to nephews.[23]

Gordon’s leadership skills had been questionable: his subordinates treated him with personal loathing and a disrespect subversive of good military order. Thomas, perhaps unwittingly, found himself in the position of the sharp point of the spear. Once he took a public stance against his superior, he could not back down. He had expected the army to take up his cause, but it did not. The morning of duel, the adversaries mirrored their contentions in their dress. Gordon, insisting the contest was an affair of honor, donned civilian attire. Thomas, proclaiming till the end that he had done his duty, wore his uniform.

While Thomas expressed moral repugnance for the institution of dueling, that coincided with his refusal to accept responsibility for assaulting Gordon’s reputation, calling into question his underlying sincerity. Frederick Thomas never repudiated his accusation against Gordon. Whether originating in jealous rancor or a steadfast defense of truth, he gave his life to affirm it. Though ostensibly vindicated in trial by combat, two centuries later Thomas continues to cast a shadow over Gordon’s honor.[24]

[1]John W. Jackson, With the British Army in Philadelphia (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1979), 263. Joseph Lee Boyle, From Redcoat to Rebel: The Thomas Sullivan Journal (Westminster, MD, Heritage Books: 2006), 219.

[2]John Fanning Watson, Historic Tales of the Olden Time of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Little & Holden, 1833), 289.

[3]Winthrop Sargent and William Abbatt, The Life and Career of Major John Andre, Adjutant-general of the British Army in America. (New York: W. Abbatt, 1902), 276-277. William Nelson, “A Red Rose – Springfield 1780 – and After” in Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, no. 2 (1917): 1-6. John Malcolm Bulloch, The Gay Gordons: Some Strange Adventures of a Famous Scots Family (London: Chapman & Hall, 1908), 159-164. “Historical Music Performed,” The Frederick News-Post, March 11, 2016, www.fredericknewspost.com/places/local/frederick_county/historical-music-performed/article_99461135-5aba-568d-be11-6e67192b35d5.html. Sarah Murden, “A Duel in Hyde Park,” All Things Georgian, September 4, 2018, georgianera.wordpress.com/tag/colonel-cosmo-gordon/.

[4]The Scottish Peerage, sites.google.com/site/thescotspeerage/aberdeen-gordon-earl-of/william-gordon-2nd-earl-of-aberdeen.

[5]Testimony of [?] Derolls, The Trial of Cosmo Gordon, Esq.; Commonly Called The Honourable Cosmo Gordon, for the Willful Murder of Frederick Thomas, Esq.; in a Duel in Hyde Park, on the Fourth of September, 1783 (London, E. Hodgson: 1784), 1045 (Murder Trial), www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?name=17840917. Derolls was employed by His Majesty at Brussels, possibly in a diplomatic capacity, when he became acquainted with Gordon. Don N. Hagist, “Untangling British Army Ranks,” Journal of the American Revolution (May 19, 2016). allthingsliberty.com/2016/05/untangling-british-army-ranks/. Kenneth Pearson, 1776: the British Story of the American Revolution (London: Times Books, 1976) 109-110. The Trial of Lieut. Col. Thomas, of the First Regiment of Foot-Guards, on a Charge Exhibited by Lieut. Col. Cosmo Gordon, for aspersing his Character, by accusing him of Neglect of duty before the Enemy, as Commanding Officer of the First Battalion of Guards, on the 23rd of June, 1780, near Springfield, in the Jerseys (London: Printed for J. Ridley, 1781),12 (Thomas Trial). Andrew Cormack, “Honour Satisfied? The Courts Martial in the Brigade of Foot Guards Arising from the Action near Springfield, New Jersey, 23rd June 1780,” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research91, no. 366 (2013): 81-91.

[6]William W. Burke and Linnea M. Bass, “Preparing a British Unit for Service in America: The Brigade of Foot Guards, 1776,” The Military Collector and Historian, Spring, 1995, military-historians.org/company/journal/guards/guards.htm.

[7]“Notes on the Battle of Monmouth,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography14 (1890): 47. For a detailed account of the action at the Point of Woods, see: Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 300-305.

[8]The Peerage, www.thepeerage.com/p1913.htm#i19128.

[9]Thomas Fleming, The Forgotten Victory: The Battle for New Jersey – 1780 (New York: Reader’s Digest Press, 1973). Edward G. Lengel, The Battles of Connecticut Farms and Springfield, 1780 (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2020), 21-48.

[10]David Forman to George Washington, June 17, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-26-02-0313. Washington to Nathanael Greene, June 21, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-26-02-0360.

[11]Testimony of Cosmo Gordon, Thomas Trial, 10. Lengel, The Battles of Connecticut Farms and Springfield, 85-86n8. Royal Gazette, June 29, 1780, quoted in Thomas Sedgwick, A Memoir of the Life of William Livingston (New York: J&J Harper, 1833), 351-352. Testimony of Joseph Barton, The Trial of the Hon. Col. Cosmo Gordon, of the Third Regiment of Foot-Guards, for Neglect of Duty before the Enemy, on the 23d of June, 1780, near Springfield, in the Jerseys: Containing the Whole Proceedings of a General Court-Martial, Held at the City of New-York on the 22d of August, and continued . . . to the 4th of September, 1782 (London: Printed for Geo. Harlow, 1783), 102 (Gordon trial), www.google.com/books/edition/The_Trial_of_the_Hon_Col_Cosmo_Gordon/QzBcAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=The+Trial+of+the+Hon.+Cosmo+Gordon&printsec=frontcover.

[12]John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal (New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844), 144. Testimony of Joseph Barton, Gordon Trial, 102.

[13]The Guards’ role in the Battle of Springfield is derived from extensive testimony in Thomas Trialand Gordon Trial.

[14]The first letter was reprinted in Sedgwick, Memoir, 351-352. The second letter, dated July 12, appeared in the New Jersey Journal, published in Chatham, near Morristown. That letter was reprinted in The Royal Gazetteon July 22 along with a rejoinder. My thanks to Greg Guderian, of the Newark Public Library for uncovering these letters.

[17]Cormack, Honour Satisfied, 86, states that, in the aftermath of Thomas’s acquittal, the King instructed that Gordon be tried on Thomas’s accusation, but it appears that the court martial was actually held at Gordon’s insistence. Board of General Officers, New York Report to Clinton, December 3, 1781, discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16311240. Henry Clinton to Charles Gould, January 2, 1782, discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16318246.

[20]“Duel between Colonel Cosmo Gordon and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas,” The Political Magazine and Parliamentary, Naval, Military, and Literary Journal Volume VI (London: J. Bew, 1783), 229-230.

[22]Cormack, Honour Satisfied, 82.

[23]“Cosmo Gordon,” Bath Record Office, www.batharchives.co.uk/cemeteries/bath-abbey/cosmo-gordon. Will of The Honorable Cosmo Gordon, Colonel of Blackheath, Kent, March 29, 1813, PROB 11/1542/494, discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D208849. Bulloch, Gay Gordons, 159, 164. A Selection of Favourite Catches, Glees, &c. as Sung at the Harmonic Society in the City of Bath with Rules of the Society, and a List of the Members (London: R. Cruttwell: 1797), 18.

[24]I would like to express my gratitude to James Peill, Curator of the Goodwood Collection, and Timothy McCann, Archivist of the West Sussex Records Office for their assistance.

6 Comments

Another side of Cosmo Gordon, not mentioned in the article, is that he wrote a number of the English Country Dances in Hezekiah Cantelo’s book, “Twenty-four American Country Dances as danced by the British during their winter quarters at Philadelphia, New-York, & Charles Town,” published in 1785 by Longman & Broderip in London. Two modern editions exist, one edited by the late Kate Van Winkle Keller.

In another book, Keller showed how the British occupiers of Charleston asked the local ladies to join them for weekly dance assemblies, but the ladies refused, so the British sent to London for dozens of the finest ballgowns, and they dressed the local female slaves in them for the weekly dances. The slaves were already proficient country dancers. When the British evacuated Charleston, they took with them all the slaves (freed) to Nova Scotia and eventually to Sierra Leone.

A comment worth knowing, i.e. ref. Hezekiah Cantelo, who was himself a Guardsman!

Hezekiah was a professional musician, who lived and worked in Bath, Somerset, and later in London, England. His collection of ‘Dances’ are still used by enthusiasts!!

Barry W. Cantelo

Southampton, U.K.

John,

Thanks for this very interesting insight into Cosmo Gordon’s personal life! I am trying to track down the book by Keller, as I would like to learn more.

This might be information about the “Keller book”

https://books.google.com/books/about/Hezekiah_Cantelo.html?id=g-xfHQAACAAJ

The collection of dances by Cantelo can be found online at

https://archive.org/details/imslp-american-country-dances-1785-various

I came across this article while I was looking for information about the “Mr. Cantelo” of the dance book!

Robert – I thought this was a compelling “slice of lives” piece, with its narrative flow pulling the reader right along to the unfortunate and dramatic denouement – congratulations on the research and the writing!

Hmmmn! Interesting, it would seem that JAMES, Hezekiah Cantelo’s brother, also of Bath, has been credited with having been the collector of the ‘American dances’ ; I suspect collusion and mutual benefit on distribution by the brothers? See below, and link at the bottom, for an example with James Cantelo’s name clearly printed on the scores.

Lady Louisa Lennox’s minuet – Mr Dawson’s new minuet – Miss Cornish’s minuet – Miss Wroughton’s minuet – Mr Greville’s minuet – The Honble. Col. Cosmo Gordon’s minuet

From “Twenty four American country dances, as danced by the British during their winter quarters at Philadelphia, New York and Charlestown, Collected by Mr Cantelo, musician at Bath, where they are now dancing for the first time in Britain, with the addition of six favorite minuets now performing this current Spring season.” [1785]

Surviving in a reduced keyboard version, these minuets were intended for orchestral performance, with horn and flute cues evidenced in the keyboard reduction.; cues which perhaps suggest a military band line-up.

notAmos logo

notAmos Performing Editions

1 Lansdown Place East, Bath

BA1 5ET, UK

+44 (0) 1225 316145

http://www.notamos.co.uk/detail.php?scoreid=146466