The settlers who chose to make their homes in the upper Ohio in the mid to late eighteenth century faced a wide variety of challenges to survive in this backcountry, ranging from the distance to centers of trade and population to the difficulty in practicing agriculture in old-growth forests. That this frontier, the area surrounding modern Pittsburgh and extending along West Virginia’s border with Ohio, was a theater of several wars involving the Ohio-based Indians overshadowed these hardships. A decade after the British gained control of the region in the Seven Years’ War, Americans, including elements of the Continental Army, fought to secure this backcountry as well. Regular troops were, at best, only marginally successful in their goal of stopping Indian raids on western settlements during the Revolution, and examining their failures as well as their accomplishments offers important insights into the character of frontier warfare in the eighteenth century.

The British experience in a series of campaigns in the upper Ohio against the French and their Indian allies during the Seven Years’ War highlighted several strategic and tactical concepts which would carry on into the Revolution. The French claimed control of the remote region by virtue of their presence at Fort Duquesne on the Forks of the Ohio. Edward Braddock’s campaign to capture that post in 1755 ushered in the war in earnest, and its outcome imparted grave lessons to British commanders and their provincial auxiliaries including George Washington. Although Duquesne was occupied in part by regular French forces, Indian allies formed a substantial portion of personnel defending Duquesne and its environs. Still, Braddock employed traditional methods to reduce the fort. His expeditionary force set out from Cumberland, Maryland, with a ponderously long column containing wagon loads of supplies and artillery that was so slow he detached an advance force to cover ground more rapidly. This advance force was attacked by French and Indian warriors on July 9, 1755. In combat, the British took no measures to adapt their tactics, making it “substantially easier for the Indian marksmen to do their work . . . Unable to see the Indians who sniped at them from cover, the British troops fought as best they could, directing volleys blindly into the woods.”[1] It was a defeat so devastating that “so many intrepid British officers were killed or wounded—nearly two-thirds of the total—that it led to a complete collapse of the command structure,” and hundreds of soldiers were slain.[2] The Pennsylvania and Virginia frontiers were devastated by Indian raids following the defeat.

The next attempt to capture Duquesne fared better, although not necessarily owing to its commanders’ adaptations to irregular warfare. By the time Gen. John Forbes’ campaign was launched in 1758, important changes were being implemented in the British Army. “Regular infantrymen were being trained in ‘bush fighting’ tactics, learning how to move through the woods in single file, fight in a spread-out single rank or in loose order as skirmishers,” as well as how to “avoid bunching up when attacked.”[3] While these tactical changes helped the British cause overall, they did not necessarily help Forbes—a detachment of his force was defeated soundly on the morning of September 14, 1758. After becoming disorganized in the woods, Maj. James Grant signaled his men to assemble with a piper, only to draw in an attacking body of Indians. Grant “was taken prisoner and three hundred of his men were killed, wounded, or captured.” Though a “humiliating setback,” Grant’s defeat did not spell the end the campaign. Forbes claimed victory after the French, abandoned by their Indian allies after defeating the force under Grant, evacuated the untenable post at the Forks.[4]

Overall, British efforts to secure the frontier were successful, but the war itself was won in the European fashion, with the fall of the cities of Quebec and Montreal and naval defeats in the Indian Ocean paving the way for British victory. France’s Indian allies were not defeated as combatants in their own right. It is important to note, too, that Braddock and Forbes met with logistical challenges of vast distances from their bases by building wagon roads through the wilderness to facilitate the transport of vast quantities of stores and men. Both armies were supported by the virtually limitless purse of the British Crown, yet both forces still faced considerable difficulty.

Hostilities between the British and the tribes of the Ohio took on a slightly different character, thus setting a more important precedent for the strategies of the Americans in the Revolution. In 1763, Pontiac’s War pitted a confederacy of several Indian nations against British posts in the west and carried out attacks on settlements. Although the Indians had success initially, they suffered a devastating setback at the Battle of Bushy Run, when a column commanded by Col. Henry Bouquet, headed to relieve the besieged Fort Pitt, encountered and defeated a large body of Indian warriors who’d broken off their siege to attack him. Bouquet eventually led an expedition into the Ohio country that proved to be the breaking point for the Ohio Indians’ participation in the war, and they sued for peace.[5] A regular body of troops marching on Indian towns proved to be an effective means of bringing them to heel, an important strategic lesson which Americans remembered in the next war.

Tactically, the British army did adapt to the wilderness. Partly owing to their experience in petite guerre in Europe, the army absorbed lessons in irregular doctrine and had disseminated them in military texts such as later revisions of Humphrey Bland’s Treatise on Military Discipline.[6] Americans serving alongside them implemented the lessons as well. George Washington, for example, outfitted the men of the Virginia Provincial Regiment[7] in much the same manner as one James Smith, who had been an Indian captive during much of the war. Smith wrote that “as we enlisted the men” for service in the Pennsylvania militia during Pontiac’s War, “we dressed them uniformly in the Indian manner, with breech clouts, leggings, mockesons, and green shrouds, which we wore in the same manner that the Indians do,” and beyond these aesthetic changes, “taught them the Indian discipline, as I know of no other at that time, which would answer the purpose better than British.”[8]

The Americans and British were not alone in their developments concerning frontier warfare. Ohio-based Indians learned operational and strategic lessons as well. Their raids proved extremely effective in terrorizing and demoralizing the Pennsylvania and Virginia frontiers. Perhaps most importantly, “the Seven Years’ War, terribly violent though it was, opened an opportunity for the elaboration of intertribal relations. The memory of the unions shaped by alliance with France would persist long after France developed.”[9] Their need for even greater cooperation would come soon enough.

With the French expelled, Anglo-Americans flocked to the trans-Allegheny to establish permanent settlements. The British government tried—and failed—to stem the tide of settlers flowing into the trans-Allegheny region with the Proclamation of 1763 as a means of keeping peace with the Ohio-based Indians. Tension engendered by Anglo-American encroachment as well as racial enmity sparked Dunmore’s War in the spring of 1774. It was a short conflict, but one that forced the Americans to establish a series of forts to protect the population and raise militias on their own. The royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, raised an army of militia to invade the Ohio country in a two-pronged assault, a wing of which met an army of warriors under a Shawnee Chief, Cornstalk, at the confluence of the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers at Point Pleasant. The Virginia militia was victorious, and after they’d marched on to Ohio, the Indians once again negotiated a tense peace.[10]

Thus, at the outbreak of the American Revolution, there was no major threat posed by the Ohio-based Indians. It was a tenuous situation, as observed by the British commandant at Detroit when he wrote that “any Peace between those people and any of the savage nations is liable to frequent interruptions from more causes than one . . . the frontier of Virginia in particular will suffer severely.”[11] Virginian authorities agreed. In late summer 1775 the Virginia Council ordered militia commanders in their respective counties to prepare for war. Nearly five hundred men were ordered to garrison major forts at Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Point Pleasant.[12] In the event of incursion, settlers would flee to civilian-built refuge forts for collective defense. Militia scouts patrolled areas between the forts in order to detect war parties and provide advance warning to settlers to seek shelter in the forts, and spies went far afield to detect war parties well before they reached the settlements.[13] In August 1776, the Indian commissioners at Fort Pitt warned county lieutenants of a “General Confederacy of Western Tribes” planning to attack the settlements in earnest the following year.[14] It was to prove a difficult period, one in which “the Indians of the trans-Appalachia borderlands trained their guns with more consistency, more unity, and more consequence than did any other Indians in the history of the United States.”[15]

Contemporary military and civil authorities understood that a static defense would not be enough to counter such a threat. For example, Col. David Shepherd, county lieutenant of Ohio County, Virginia, complained to the governor that he had only 350 men to guard a frontier eighty miles long.[16] His grievance did not fall on deaf ears. Contemporaries, including the governor, understood “that offensive operations alone can produce Defence [against] Indians.” The expansive, wooded territory was porous, rugged terrain, difficult to defend even if its scale was not so prohibitive. “Since the Indians could strike wherever there was a frontier cabin or village, no satisfactory system of passive defense was ever devised. None was possible.”[17]

Recognizing both the impending escalation of the war in 1777 as well as the need for greater coordination and control of the frontier militias of Virginia and Pennsylvania, Congress appointed Continental Army Gen. Edward Hand “to take measures of the defence of the western frontiers,”[18] and gave him “discretionary power as to the number of men embodied for the defence of the frontiers.”[19] Lacking a substantial formation of regular troops (although he had a few companies of the 13th Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line), Hand essentially took charge of the militias. He was known on the Upper Ohio, as he’d been posted to Fort Pitt during his service in the British Army. His posting to Fort Pitt was greeted with enthusiasm; as he was said to be “universally loved” it was surmised that “the people [would] no doubt flock to his standard and cheerfully go forth to chastise the savage foe.”[20]

The reality was quite different. Personnel and supply problems hampered American operations in the west, unlike their British predecessors. These problems persisted throughout the war. Almost simultaneous with Hand’s arrival, the regular forces he could call on were ordered to the east, and he was left with only three hundred Continentals spread out across the largest forts in the region. Although he was in command of the frontier militia, Patrick Henry reminded him that it was nominal, as only the governor could “claim the supreme command of all the Militia which are or may be embody’d in the State.”[21] It was a confusing overlap of authority.

As such, Hand had difficulty mustering enough personnel to conduct an offensive operation. He reported in November 1777 that a draft of militia had come up too short to carry the war into the Ohio Country that year.[22] The campaign he was eventually able to mount was deemed the “infamous ‘squaw campaign’” in February 1778. Intended to capture a supply post on the Cuyahoga River, it encountered only a handful of neutral Indians who were murdered and scalped. It was an inglorious end to Hand’s tour in the west.[23] The following spring at Fort Pitt, he was left with 213 regular soldiers in the 13th Virginia Regiment and additional independent companies[24] and a shortage of ammunition so dire that he wrote, “if there is not a possibility of obtaining lead, I wish we might be indulged with a cargo of bows & arrows, as our people are not yet expert enough at the sling to kill Indians with pebbles.”[25] He had by then requested a transfer.

Indian raids continued unabated. In the spring of 1778, Congress substantially escalated the Continental Army’s role in the west by resolving, “That two regiments be raised in Virginia and Pensylvania, to serve for one year, unless sooner discharged by Congress, for the protection of, and operations on the western frontiers; twelve companies in Virginiaand four in Pensylvania” and authorized Washington to appoint an overall commander for them.[26] Timothy Pickering, on Congress’s Board of War, asked Washington to send troops from the main army,[27] a measure the general had already decided upon. He “had put that part of the 13th Virginia Regt [at Valley Forge] . . . under marching orders” and “orderd the 8th Pennsylvania Regt to march. They were also raised to the Westward and are a choice Body of Men, about one hundred of them have been constantly in Morgans Rifle Corps.” Washington chose the remaining portions of the 13th Virginia and the 8th Pennsylvania partly because of their suitability to frontier duty as well as with the hopes that deserters from those units would return “when they find their Regiments are to do Duty in that Country.”[28] Washington ordered Gen. Lachlan McIntosh to lead them.[29] It was a drastic measure, considering that this detachment marched off after the Army’s winter at Valley Forge. Washington remarked that he could “very illy spare the Troops which I have sent.”[30]

When the troops of the 13th Virginia and 8th Pennsylvania arrived at Fort Pitt in the late summer 1778, they, along with a handful of North Carolina Dragoons and several French officers, constituted the largest force of regular soldiers assembled west of the Alleghenies. The eventual goal of this force was to capture or otherwise reduce the main British stronghold in the west, Fort Detroit, which would in turn eliminate the Indians’ source of supply and direction. Although it was known that Detroit was out of reach that campaign season, General McIntosh set about planning an ambitious assault into the Ohio Country, a projection of force that the Americans hoped would relieve pressure on the settlements in Pennsylvania and Ohio and serve as a springboard for later operations to attack Detroit. The campaign that followed was the most significant undertaking by Continental forces in the region, and one that most clearly illustrates the problems inherent in service on the upper Ohio.

In the fall of 1778 the Continentals and attached militia of the Western Department set out on their expedition. There were “three primary goals; to build a road from Pittsburgh to the mouth of the Beaver River on the Ohio, to build a fort at that site, and to push on to the Ohio country to build a fort on the Tuscarawas River.” The road building effort took approximately three weeks, and Fort McIntosh on the Beaver River was left half completed while the main body, about 1,200 men, proceeded to the Tuscarawas. They arrived there on November 19 and began construction on Fort Laurens. Fort Laurens would serve many roles, including serving as a staging area for an eventual campaign to capture Detroit as well as defending the American-allied Delaware towns nearby.[31] After largely completing the fort, General McIntosh left a garrison of 150 men under Col. John Gibson of the 13th Virginia, and marched out with the remainder of the army to return to Fort Pitt by way of Fort McIntosh.[32]

The campaign was beset by problems. Discipline among the troops, both regular and militia, was poor. On one occasion “Some Persons as y[e]t unknown have Prosumed to mark trees in the woods . . . [which] give[s] great uneasiness to our good friends and allies ye Delwar nation.”[33] The random firing of guns in the column was so widespread that on a day that the practice did not occur, the general saw fit to reward the militia by allowing them a reprieve from fatigue duty and the chance to hunt.[34] Supplies were scarce. At the time of the November expedition, there were only two months’ worth of flour in the entire Western Department.[35] Transporting these supplies from Fort Pitt to posts further out was nearly impossible “owing to the scandalous Pack Horses that were imposed upon me” that tired out after a march of two or three miles.[36] So late in the season, the animals had no natural forage sufficiently nutritious to sustain them anyway. In addition to these difficulties, the hostile Indians of the Ohio country constantly harassed and sometimes attacked the column on the march, as was the case when two soldiers wandered out to hunt and were killed and scalped on November 8, 1778.[37] The garrison of Fort Laurens fared much worse.

In late February 1779, a work party of nineteen soldiers that sallied out of Fort Laurens was ambushed by a large war party of Indians led by British soldiers of the 8th Regiment of Foot[38] that killed seventeen of them. The ambush itself was grisly, the remains of the slain indicating “trauma associated with close quarters combat.” One had his arm broken and hand severed as he tried to shield himself from tomahawk blows.[39] The ambush marked the beginning of a month-long siege. The Indians and British surrounding the fort fired upon it with little effect, but the Continentals’ lack of provisions was keenly felt. The men were reduced to half a biscuit a day at one point, inducing desperation so acute that some men cooked their moccasins and strips of old hides to stave off hunger.[40] After the siege lifted, largely because the Indians abandoned the attack,[41] a relief column led by General McIntosh arrived. When it came in sight of the fort, the defenders fired a volley to welcome them, and the greater part of the packhorses carrying fresh provisions was scattered. Only a few were recovered, and some of the men in the starving garrison died from overeating on their “weak stomachs.”[42]

General McIntosh wanted to attack the Indian towns on the Sandusky with the force he had collected at Laurens, but a council of war disagreed, citing the scarcity of supplies and the poor condition of the road. Instead, he left a hundred men of the 8th Pennsylvania under Maj. Frederick Vernon at Fort Laurens and marched back to Fort Pitt. In the spring, General McIntosh requested and received a new posting, leaving Col. Daniel Brodhead, commander of the 8th Pennsylvania, temporarily in command of the Western Department.[43]

Brodhead fared nearly the same as his predecessor. In the fall of 1779, he commanded an army of more than six hundred men in a march up the Allegheny River to attack the Seneca Indians in conjunction with Sullivan’s campaign further to the north. He found only deserted towns, and “through the incompetence of his guides was unable to join the other American forces and turned back.” In the spring of 1781, when the Delaware nation was said to be disposed against the Americans, Brodhead led a campaign to destroy one of their major towns, Coshocton, in central Ohio. After killing fifteen warriors, capturing twenty women and children, and looting tens of thousands of dollars in booty, the rest of the expedition was abandoned.[44] It was an anticlimactic end to an inglorious war in the west. The Continentals engaged in no major operations after the Coshocton campaign. In the end, Gen. William Irvine commanded less than three hundred men who, “naked and starving . . . were often close to mutiny.”[45]

The Americans never realized the goal of capturing Detroit; it proved elusive even to the often-lionized militia commander George Rogers Clark. Nor did they stem the tide of hostile raids. Indian attacks on the frontiers of western Pennsylvania and Virginia continued for more than a decade following the end of the Revolution. One contemporary remarked that during the period “the government could not furnish the means for making a conquest of the Indian nations at war against us. The people of the western country, poor as they were at the time, and unaided by government, could not subdue them,”[46] as if to suggest that there was no national effort made to secure the upper-Ohio frontier.

Several factors played a role in the ultimate failure of the Continental Army to secure a strategic victory against the Ohio-based Indian nations or to provide an adequate defense against raids. General McIntosh, in an oft-repeated voicing of complaints, put the issue succinctly: “The difficulty in getting [supplies] over, and the distance of carriage, is the grand objection to every enterprise in this quarter.”[47] To the shortage of supplies experienced by the Continental Army as a whole, then, was added the extra difficulty of hundreds of miles of travel over terrain so rough that packhorses or watercraft were the only viable means of transport. Nor were there nearly enough men to undertake such an endeavor. The Western Department as an independent command was also woefully undermanned. The militia of western Pennsylvania and Virginia formed a significant portion of the personnel at the commanders’ disposal; often more than half of an expedition was comprised of militia troops. Again, this was not a situation unique to the west, as militia augmented Continental formations in the northern and southern theaters of operation against the British Army as well.

When viewed in the context of these difficulties, the Continental Army in the Western Department still managed to accomplish quite a lot. They conducted limited offensive operations, which, although only marginally successful in their aims, still represented their ability to project force into the Ohio country. At Fort Laurens, for example, elements of the army managed to withstand a bitter siege deep within enemy territory without capitulating. Like their counterparts facing the British on the eastern seaboard, perhaps the Continentals’ most stunning achievement was that they did not disintegrate entirely. It is telling of the experience of the Continental Army in the west that General Hand offered a toast to a group of officers in September 1779: “May the Enemies of America be Matamorphised in Pack horses and sent on a Western Expedition.”[48]

[1]Fred Anderson, The War That Made America: A Brief History of the French and Indian War (New York: Penguin, 2005), 69-73.

[2]Ron Chernow. Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin, 2010), 59-60.

[3]Anderson, The War That Made America, 129.

[5]Jack M. Sosin, The Revolutionary Frontier, 1763-1783 (Albuqurque: University of New Mexico Press, 1967), 6-10.

[6]Glenn F. Williams, Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era (Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2017), 126-131.

[8]James Smith, Scoouwa: Jame Smith’s Indian Captivity Narrative (Colombus: Ohio Historical Society, 1978), 120-121. Originally published as: James Smith, An Account of the Remarkable Occurrences in the Life and Travels of Col. James Smith (Lexington: John Bradford, 1799).

[9]Gregory E. Dowd. A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745-1815 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1992), 26.

[10]Sosin, Revolutionary Frontier, 85-87.

[11]Henry Hamilton to Guy Carleton, December 4, 1775 in Louise Kellog and Rueben Thwaites, eds., The Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 1775-1777 (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1908), 127-130.

[12]Thomas Lewis to William Preston, August, 19, 1775 in ibid., 21-24.

[13]Williams, Dunmore’s War, 131. For a detailed look at the scouting operations on the frontiers, see Matt Wulff, Ranger: North American Frontier Solider, Vol. II (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2011).

[14]Commissioners of Indian Affairs to County Lieutenants, August 31, 1776 in Kellog and Thwaites, eds., Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 190-191.

[15]Dowd, Spirted Resistance, 59-60.

[16]David Shepherd to Patrick Henry, March 24, 1777 in Kellog, Thwaites, eds., Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 242-243.

[17]John K. Mahon, “Ango-American Methods of Indian Warfare, 1676-1794,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 4, No. 2 (1958), 262.

[18]Congressional Resolution, April 10, 1777 in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Vol. VII, 252, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: US Congressional Documents and Debates” Library of Congress, memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwjclink.html.

[19]Congressional Resolution, April 11, 1777 in ibid., 256.

[20]Excerpt, The Maryland Journal, May 20, 1777 in Kellog and Thwaites, eds., Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 255-256.

[21]Henry to Edward Hand, July 4, 1777 in Louise P. Kellog and Reuben G. Thwaites, eds., Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 1777-1778(Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1918), 16-18.

[22]Hand to George Washington, November 9, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0171(original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002), 179–180).

[23]Direct quote in, Don Higgenbotham, The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Polices, and Practice, 1763-1789 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1971);Sosin, Revolutionary Frontier, 111.

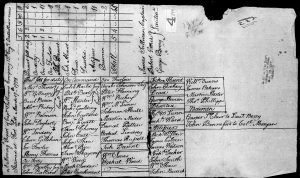

[24]“Gen. Return of the Strength of the Garrison of Fort Pitt, April the 19th1778,” Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives and Records Administration. M246, Roll 114, fold3.com/image/#246/9946980.

[25]Hand to Richard Peters, July 10, 1778 in Louise P. Kellog and Rueben G. Thwaites, eds., Frontier Advance on the Upper Ohio, 1778-1779 (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1916), 107.

[26]Resolution, Journals of the Continental Congress, 416-417.

[27]Timothy Pickering to Washington, May 19, 1778 in Frontier Advance, 55-56

[28]Washington to Pickering, May 23, 1778 in ibid., 57.

[29]Washington to Lachlan McIntosh, May 26, 1778 in ibid., 60.

[30]Washington to Pickering, May 23, 1778 in ibid., 57.

[31]Robert Cairns, “History of the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment, 1776-1783,” Military Collector and Historian, Vol. 59, No. 4, Winter 2007, 253-254. 8th Pennsylvania Regiment, Fort Laurens Detachment, http://www.mtbumc.org/8thpa1776/history.html.

[32]Thomas I. Pieper and James B. Gidney, Fort Laurens, 1778-1779: The Revolutionary War in Ohio (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1976), 40-41.

[33]Brigade Orders, October 22, 1778, Edward G. Williams, ed., “A Revolutionary Journal and Orderly Book of Gen. Lachlan McIntosh’s Expedition, 1778,” TheWestern Pennsylvania Historical MagazineVol. 43, No. 2 (June 1960), 166,journals.psu.edu/wph/issue/archive.

[34]General Orders, November 29, 1778, “Orderly Book of the Eight Pennsylvania Regiment” in Kellog, ed. Frontier Advance, 448.

[35]Richard Campbell to McIntosh, November 18, 1778 in Thwaites, ed., Frontier Advance 174-175.

[36]McIntosh to Campbell, November 13, 1778 in ibid., 172-173.

[37]Journal Entry, November 7, 1778, “Robert McCready’s Journal” in Edward Williams, ed.,“A Revolutionary Journal and Orderly Book,” The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Vol. 43, No. 1 (March 1960), 12.

[38]Pieper and Gidney, Fort Laurens, 58.

[39]Kyle Somerville, “A Case Study in Frontier Warfare: Racial Violence, Revenge, and the Ambush at Fort Laurens, Ohio,” Journal of Contemporary Anthropology,Vol. 2, No. 1 (2011).

[40]Recollections of Benjamin Biggs in Kellog, ed., Frontier Advance, 256-257.

[41]Pieper and Gidney, Fort Laurens, 60-61.

[42]Recollections of Henry Jolly in Kellog, ed., Frontier Advance, 257.

[43]Pieper and Gidney, Fort Laurens, 64-65.

[45]Sosin, Revolutionary Frontier, 135-136.

[46]Joseph Doddridge, Notes on the Settlement and Indian Wars of the Western Parts of Virginia and Pennsylvania from 1763-1783, inclusive together with a Review of the State of Society and manners of the First Settlers of the Western Country(Akron: The New Werner Company, 1912), 216 (originally published in 1824 by Joseph Doddridge).

[47]McIntosh to Washington, March 19, 1779 in Kellog, ed. Frontier Advance, 256.

[48]Frederick Cook, ed., “Journals of Lieutenant Erkuries Beatty, 4th Pennsylvania Regiment, September 25, 1779,” Journals of the Military Expedition of Major Gen. John Sullivan Against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779; with Records of Centennial Celebrations; Prepared Pursuant to Chapter 361, Laws of the State of New York, of 1885(Auburn: Knapp, Peck, and Thomson, Printers, 1887), 34.

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...