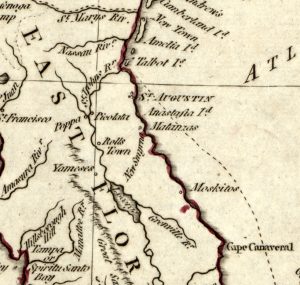

In March 1777, while Andrew Turnbull was away in England, several Minorcans escaped New Smyrna and fled to St. Augustine, East Florida. They hiked seventy to eighty miles from Mosquito Inlet to the colony’s capital. Arriving there safely, they complained to East Florida Gov. Patrick Tonyn about the struggles and depravations they endured at New Smyrna. After hearing their grievances, Tonyn promised to protect the settlers if they testified in court. Overwhelmed with the abundance of available testimonies that he deemed too many and too troublesome for extensive examination, the attorney general requested that only a few represent the whole New Smyrna settler population.[1] On May 7, 1777, seventeen New Smyrna colonists drafted official affidavits to the British East Florida government; their names were Lewis Cappelli, Babpina Patchedebourga, Anthony Stephonopoli, Nicola Demalache, Giosefa Marcatto, Pompey Possi, Pietro Cozisacy, Louis Margan, Giosefa Lurance, Juan Partella, Rafael Hernandez, Michael Alamona, Juan Serra, Rafael Simines, Christopher Flemming, Pietro Musquetto, and Lewis Sauche.[2] Each man produced an affidavit, sometimes two, detailing their experiences at New Smyrna. Ten colonists signed their names while seven simply left an X. According to historian Patricia Griffin, the deponents were probably the most literate of all the New Smyrna settlers.

Only seven Minorcan islanders were represented in court.[3] The rest were Greeks and Italians. Justice of the Peace, Spencer Man, was directed to hear the settlers’ complaints.[4] Prior to the official proceedings, the settlers were instructed to swear an oath to the court speaking to the truthfulness of their claims. An interpreter, Joseph Purcell, was present to help translate the Minorcan dialect. In the end, seventeen testimonies spoke for the hundreds of settlers back at New Smyrna. Their stories shocked and perturbed British officials. According to Tonyn, Turnbull’s colonists experienced “Injustice, Tyranny and Oppression, exercised to a degree disgraceful to His Majesty’s Government.”[5]

Lewis Cappelli (signed Luigi Cappelli in his affidavit) claimed that on June 15, 1773 he was in Dr. Turnbull’s shop making cart wheels. Mr. Watson, probably an overseer, determined that the wheels were too crooked and ordered them redone. Cappelli followed Mr. Watson’s instructions carefully, completing his task exactly as directed. In two days, heat from the sun warped the wheels making them too short. Mr. Watson then called Cappelli a “Negroe Son of a Bitch” before taking four sticks, each one-inch thick, and breaking them upon Cappelli’s back.[6] Following this incident, Lewis Cappelli remained physically unfit for two weeks but was forced to work anyway. After six years’ service for Dr. Turnbull, Cappelli applied for his discharge. Turnbull informed Cappelli that he would not grant him his discharge. For his “audacity,” Cappelli was imprisoned and a chain was fastened on his leg. He was starved and deprived of company. Sometime after his confinement, he was tied to a tree and lashed twelve times. In the wake of his flogging, Cappelli was put in the pillory for six days after which he was released and put back to work. During his entire residence at New Smyrna, Cappelli claims he was compelled to live with only one blanket for nine years.[7]

Babpina Patchedebourga claimed that he agreed to serve Dr. Turnbull for six years and that during his indenture the doctor promised to provide him with good food and water. Additionally, he was assured a payment of five pounds sterling a year. Apparently, Turnbull never honored his end of the bargain. Patchedebourga was not paid nor given a fresh set of clothes in years. He served out his indenture and then some but refused to speak out because he was afraid of being flogged and put in irons. He travelled to St. Augustine to secure his discharge.[8]

Anthony Stephonopoli’s contract only demanded that he work six years, but he ended up serving nine years and four months. He was withheld food, water, and pay—everything he was promised when he signed on. When he attempted to run away, he was caught and lashed 110 times on his naked back. He was also chained by the leg and quartered in a locked room every night. He would have died had the other settlers not fed him raw peas and corn. When his indenture was up, he went to Turnbull to request his release. The doctor refused and informed him that “he would not give it to him.” Turnbull then forced Stephonopoli to sign a paper, binding him to service for another four years. Stephonopoli signed because he feared he would be put to death if he refused.[9]

Nicola Demalache provided an account of his cousin, Peter Demalache. Peter was bound to serve Turnbull for six years. One day, he became sick. Bedridden, he was unable to work in the fields. When the overseers caught wind of his absence, they paid him a visit. Poor Peter was driven out of bed with a stick. He was forced to work despite his illness. Sometime after this incident, Peter was bed ridden once again. An overseer named Nichola Moveritte came to his bedside and ordered him to work. He could not. According to Demalache’s testimony, Peter was quite ill and unable to effectively perform his duties. Moveritte starved Peter for his “laziness.” One night after a long day’s work, the New Smyrna settlers cooked their supper when a cry issued out across the plantation. Peter Demalache begged “for Gods sake to give [me] a little broth.” Moveritte ordered the settlers not to give him a drop. Peter was left alone all night. The next day, Peter Demalache was found dead. His body was covered in mosquitos.[10]

Giosefa Marcatto was bound to Turnbull for six years. During his tenure at New Smyrna, he worked days and nights, received no time off, and almost starved to death. Because of his miserable reality, Marcatto ran away. He was caught, brought back, and imprisoned with his legs clapped in irons. At one point, he was tied to a tree and whipped 113 times. Afterwards, he was sent to work with a chain attached to his leg. He was forced to wear the chain for six months. One day, when Dr. Turnbull appeared on the field, Marcatto went to him and begged him to take the chain off. “Get out you scoundrel,” Turnbull said, “it is not time yet.” With his indenture completed, Marcatto went to Turnbull and requested his discharge. Turnbull refused to acquiesce to his request and instead put him in a pillory for several days. He was not permitted to speak to anyone. Sometime later, Turnbull informed Marcatto that he must agree to serve him for four more years. If he did not agree, he would be put to work alongside the “Negroes.” Out of fear of continued harassment and maltreatment, Marcatto signed Turnbull’s papers thereby extending his indenture at New Smyrna.[11]

Pompey Possi claimed that Dr. Turnbull came out into the field and accused him of not working. Possi said he did his work just as well as everyone else. Displeased with the response, Turnbull beat Possi and “struck him in his private parts.” After this assault, Possi resigned to a field hut floor for the rest of the day. He did not make it back home that night. Other encounters at New Smyrna found Possi stripped naked, whipped, beaten, and dragged through a field. On one account, Turnbull broke two sticks upon poor Possi before holding him up by his hair and beating him until he grew tired.

Possi’s cousin, Anthony Blaw, suffered a darker fate. Prone to sickness, Blaw was not popular among the plantation overseers. One day, he was so tired from cutting down a tree he fell over. The overseer on-site, Louis Pouchintena, called him lazy and beat him. Following the beating, Pouchintena noticed Blaw did not get up. Reaching down, he checked Blaw’s pulse. Blaw was dead. Possi wrote about one more settler, Anthony Lavay. Lavay was bound to Turnbull for six years. Without warning, an overseer told him that he did not do his work well enough to which he replied, “[I] had done it as well as the rest.” The overseer reported to Turnbull what Lavay said. The next day, Turnbull unleashed twenty lashes on Lavay’s naked back.[12]

Pietro Cozisacy agreed to serve Turnbull for six years. Due to his miserable reality at New Smyrna, Cozisacy attempted to escape. On his second failed attempt he was caught and given fifty lashes. A chain was also fixed around his waist. Weighing twenty-eight pounds, a blacksmith’s hammer was tied to this chain. He was forced to wear it around for a month. After he served out his punishment, he applied to Turnbull for his release. According to their arrangement, his indenture was completed. Turnbull refused to grant him his discharge on account of his escape attempts. The doctor then informed him that his indenture was extended for another four to six years.

Apart from his own experience, Cozisacy also recounted an incident that happened to Turnbull’s cook. When an unnamed gentleman visited New Smyrna, he gave the cook, Francisco Sego, a dollar. After Turnbull discovered the dollar, he tied Sego up and whipped him twelve times. Lastly, Cozisacy talked about the persistent hunger suffered by the New Smyrna colonists. According to Cozisacy, the settlers were so desperate for food they cooked up cowhide, a material given to them to make moccasins.[13]

Promised good food, pay, and a new suit of clothes every year, Louis Margan agreed to serve Turnbull for five years as a blacksmith. He received nothing for his services at New Smyrna. Once his indenture was completed, he requested his discharge. Margan endured fifty lashes for his solicitation. He was also imprisoned and denied sustenance save for a little corn and water. Due to her husband’s absence from the field, Margan’s wife was required to pick up the slack. With Margan in jail and his wife working to meet the demands of her indenture, no one was left to care for the couple’s infant son. Margan’s wife was only able to breast feed the baby two times a day before she had to return to work. After two weeks in prison, Margan was released under the condition that he remain at New Smyrna for five more years. Failure to accept those terms would put him back in jail. Because of his family’s dire situation, Margan agreed to extend his indenture.[14]

Giosefa Lurance agreed to farm New Smyrna for ten years. During his service, he received none of the victuals or clothes promised to him save for one jacket. One day, Lurance endured great difficulty moving a heavy log. He told the overseer, Simon, that he could not carry it. Simon came up behind him and knocked him down causing the log to fall upon his breast. This permanently disabled Lurance. From then on, he was physically unable to perform his work duties properly.

Lurance’s testimony recounted another incident at New Smyrna. Simon approached Paola Lurance, Giosefa Lurance’s sister-in-law, and asked her to sleep with him. She told him she would not. Without pestering her further, Simon walked off. Two or three days later, Simon found fault with Paola’s work and proceeded to beat her with a stick. She begged him to stop, saying she was with child and his beatings could kill her unborn infant. “I don’t care for you nor your Child, I don’t care if you both go to Hell,” he replied. After her beating, Paola went home. Three days later she gave birth to a dead baby.

Simon even came after Giosefa Lurance’s brother, Matthew Lurance. When a belly ache hindered Matthew’s ability to work, Simon called him a lazy liar and proceeded to beat him with a large stick until it was worn out. He then beat Matthew with his fist and then his feet until he was tired. Simon then went to a place where other people were working and told them he just beaten Matthew and that he would go back and do it again. He did. After his beating, Matthew got up and went to bed. He died three months later. Subsequently, an out-of-the-blue illness caused James Grunulons, Giosefa Lurance’s neighbor, to remain in his sleeping quarters. Simon broke a stick over him for being a “lazy liar.” He then beat him with his fists until he was tired. Two or three days later, Grunulons died in his bed. Lurance claimed that the beating hastened Grunulons’ death.[15]

Shoemaker Juan Partella agreed to serve Turnbull for five years. Instead of making shoes like he was brought on to do, he was put to work in the fields. Not used to field work, Partella was unable to perform his duties as well as his counterparts. The overseers punished him for his inexperience. He was starved and whipped. Sometimes he was whipped with three sticks at the same time. In time, Partella came to work under another overseer, Louis Sauche. Turnbull instructed Sauche to beat the settlers very hard. If he happened to kill any, he was ordered to pay no mind to the deed. “If you want to kill a man, you may do it yourself for I will not,” Sauche replied. “If you don’t, I will break you and put another in your place,” Turnbull said. On a separate occasion, Partella’s wife pulled an ear of corn and cooked it in the field. When Moveritte caught wind of this, he beat and stomped on her. She never recovered.[16]

Rafael Hernandez agreed to serve Turnbull for six years. He was sent to the Pine Barren to cut timber when he received word from the plantation that his wife was dying. He left his post to go see her. When the overseer discovered Hernandez’s disappearance, he wrote to the plantation, incorrectly informing the overseers there that Hernandez had run away. When Hernandez reached the plantation, he was imprisoned and refused the opportunity to see his wife. When he was released, he was sent back to the Pine Barren. In time, the overseers deemed Hernandez’s work unsatisfactory. To correct his work ethic, they starved him. Owing to his hunger, he was forced to eat corn husks picked out of campfire ashes. He was also whipped twenty times on his bare back and hit with roasted Hickory sticks until they broke. After the overseers had their way with him, Hernandez lost the power of his finger.[17]

Michael Alamona’s testimony recounted the tale of Biel Venis, a ten-year-old boy. One day he got sick and told an overseer, Lewis Pouchintena, that he was unable to work. Pouchintena beat him and drove him out into the field. Still unable to work, Venis was brought to a stump. Pouchintena ordered Michael Alamona and the other fieldhands to pelt Venis with stones. If they refused to cooperate, Pouchintena warned, the same fate awaited them too. Against their will, Venis was stoned to death. According to Alamona, Pouchintena also killed two other settlers. Anthony Row was beaten so badly he died leaning against a tree. Anthony Musquetto died from starvation and beatings.[18]

Juan Serra agreed to serve Turnbull for seven years. He was promised food, drink, and pay. Since he began his service with Dr. Turnbull, he received nothing of the sort. When his seven years’ indenture was completed, he applied to Turnbull for his discharge. Turnbull refused him. Instead, he tied Serra up and whipped him twelve times before clapping him in irons.[19]

Rafael Simines looked after Dr. Turnbull’s horses. He was accountable for cutting grass to feed those horses. Simines claimed he was starved which hindered his ability to cut optimal amounts of grass. A horse whip unfairly punished him for his alleged inefficiency every morning. If Simines happened to catch any oysters or fish to alleviate his hunger, they were all taken away. Without a choice, Simines was forced to kill and eat snakes or other vermin. He was also flogged and forced to flog others or else face punishment. He wore the same pair of clothes for three years.[20]

Pietro Musquetto claimed that Moveritte killed his elderly father, Anthony Musquetto. When Anthony was unable to work, Moveritte beat him severely with a large stick. He died two hours later. Pietro believed the beating caused his father’s death. Sometime after the fact, Moveritte turned to Pietro and said he would kill him like he did his father.[21] On another occasion, Pietro witnessed Moveritte throw an axe at settler Joseph Spinata. He missed Spinata, but the axe struck another man standing directly behind him. The axe buried itself in the man’s head, killing him instantly.[22]

Christopher Flemming agreed to serve Turnbull for seven years as a carpenter. He was promised good food, drink, and wages, but was given none of them. When his indenture was completed, Turnbull refused to discharge him. Prior to the doctor’s departure to England in 1776, Flemming approached Turnbull and requested his discharge. Turnbull struck him and said he would not let him go until he thought proper.[23]

Lewis Sauche agreed to serve Turnbull for six years. After his six years, he applied for his discharge. Turnbull refused. Sauche was imprisoned and chained to the wall. Turnbull then produced a false contract with Sauche’s name subscribed to it. The contract extended his indenture for another ten years. Two witnesses’ signatures, Pietro Merlin and Gasper Trotti, were affixed to the document. After waiving the document in his face, Turnbull informed Sauche that he was not going anywhere. Later, Merlin and Trotti told Sauche that Turnbull forced them to forge the contract. They would have been flogged had they turned down the doctor’s directive.[24]

At length, East Florida’s courts ruled in Turnbull’s favor and ordered the settlers to return to their indentures.[25] In July 1777, Tonyn informed secretary of state George Germain that the New Smyrna settlers were liberated. He notified Germain that small lots of land were given to the families of the freed settlers.[26] In reality, Tonyn disregarded the court’s decision to return the workers back to Turnbull’s plantation. He instead encouraged the colonists to settle in St. Augustine where he assured them that he would protect them. As a result of Tonyn’s murky treatment of the law, most of New Smyrna’s settlers abandoned the plantation and relocated in St. Augustine. During their time in the colony’s capital, they were almost forgotten. Land was never doled out to them and many were forced to beg in the streets or find sustenance in fishing—they were wholly ignored by Tonyn.[27] Desperate for coin, many joined the East Florida Rangers.[28] While in military service, some were dispatched to the Florida-Georgia border where they allied themselves to the Native Americans against American settlers.[29] Turnbull’s former colonists went on to grapple with uncertain futures brought about by the Revolutionary War. As for New Smyrna, the plantation continued to operate and export produce, but only at a fraction of its potential. The settlement would never recover financially from its virtual abandonment in the wake of Tonyn’s intervention and the testimonies that shed light on the brutal reality endured by those who called New Smyrna their home.

[1]Epaminondes P. Panagopoulos, New Smyrna: An Eighteenth Century Greek Odyssey (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1966), 149.

[2]List of Mutineers of the Turnbull Settlement, May 7, 1777, Carita Doggett Corse, transcriber, The Turnbull Papers (Jacksonville, 1940), 179.

[3]Patricia C. Griffin, Mullet on the Beach: The Minorcans of Florida, 1768-1788 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1991), 98-99.

[4]Henry Yonge to Patrick Tonyn, May 8, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 214-215.

[5]Tonyn to George Germain, May 8, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 211-213.

[6]Luigi Cappelli’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 180.

[7]Luigi Cappelli’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 181.

[8]Babpina Patchedebourga’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 182.

[9]Anthony Stephonopoli’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 183-186.

[10]Nicola Demalache’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 187.

[11]Giosefa Marcatto’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777,The Turnbull Papers, 188-189.

[12]Pompey Possi’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 190-192.

[13]Pietro Cozisacy’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 193-195.

[14]Louis Margan’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 196-197.

[15]Giosefa Lurance’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 198-200.

[16]Juan Partella’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 201-202.

[17]Rafael Hernandez’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 203-205.

[18]Michael Alamona’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 206-207.

[19]Juan Serra’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777,The Turnbull Papers, 208.

[20]Rafael Simines’ Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 209.

[21]Pietro Musquetto’s Affidavit, May 7, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 210.

[22]Pietro Musquetto’s Affidavit, May 10, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 217.

[23]Christopher Flemming’s Affidavit, May 9, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 216.

[24]Lewis Sauche’s Affidavit, May 20, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 218-219.

[25]Carita Doggett Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and the New Smyrna Colony of Florida (Jacksonville, Florida: The Drew Press, 1919) 157-159, 163.

[26]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, July 26, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 220.

[27]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 164-165.

[28]Andrew Turnbull to Earl of Shelburne, November 10, 1777, The Turnbull Papers, 221.

[29]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 170.

One thought on “Seventeen Testimonies Seal New Smyrna’s Fate, 1777”

I already knew about New Smyrna, but never realized the atrocities that occurred there.

Also, the testimonies of the survivors really make you understand how indentured servitude was basically forcing people into slavery through deception and false promises.

As an Italian-American I thank you deeply, George, for this article.

It boggles my mind how we as a country completely forget—or decide not to—to study and remember the millions of Irish, British, Italians, Greeks, Asians, etc. that had to go through indentured servitude.