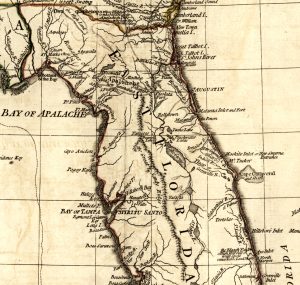

Beyond Florida’s state boundaries the history of New Smyrna is seldom mentioned.[1] Well known to the locals of New Smyrna Beach, the region’s settlement by European colonists dates to 1768 when Scottish physician Andrew Turnbull led a colonization effort to Britain’s far flung outpost in North America. After a trip to Asia Minor and the Mediterranean, Turnbull married Maria Gracia Dura Bin from Greece. While in the Mediterranean, Turnbull hatched the idea of colonizing Florida with Mediterranean folk, people from a climate similar to that of Florida and skilled in the raising of semitropical products.[2] Turnbull immediately recruited colonists after securing financial backing for his vision and acquiring 20,000 acres of land on the Florida frontier.[3] Most settlers who agreed to go with him were from the island of Minorca. In total, 1,403 people sailed under Turnbull’s patronage in the spring of 1768.[4] After arriving at St. Augustine, Turnbull made the decision to settle Mosquito Inlet,[5] establishing New Smyrna in early August.[6]

According to eighteenth century naturalist William Bartram, New Smyrna was established on a “high shelly bluff, on the West bank of the South branch of Musquito river.” During the time of Bartram’s visit, the area was a large orange grove containing “oaks, magnolias, palms, [and] red bays.”[7] Upon the colonists arrival, they were under contractual obligation to work for Turnbull for a number of years until they were granted their freedom; in the meantime, they were allowed to retain half of the crops they raised.[8] Life at the plantation was not what the colonists had expected. New Smyrna had to literally be carved out of the wilderness. To give perspective on how deep into the frontier this settlement was, St. Augustine was seventy miles north of the colony. The need, then, to establish a working settlement was of the utmost importance. Until the cultivation of crops became a reality, the land would not support the settlers. The work of carving out civilization in the Florida tropics demanded hard work. Turnbull employed overseers, former British army noncommissioned officers, to keep the settlers (his investment) working. Hard days were met with a scarcity of available food. Sure, there were plenty of fish in the lagoons, but the settlers were not permitted to divert time and energy away from constructing a plantation, which was worked on seven days a week—the workers often receiving no days for rest. Those poor colonists who dared lag behind optimal productivity endured harsh punishments including floggings.[9]

As they found out soon after their arrival, settlers suffered brutal working conditions which contributed to a high death rate.[10] Other factors that caused numerous deaths were starvation, scurvy, dropsy, lack of sanitation, yellow fever, typhoid fever, and pneumonia.[11] After a long day’s work in the hot summer heat with the sun beating down on their necks, mosquitos visited the settlement at night, sometimes carrying malaria. Settlers wore rags and slept on bedding found to be in poor condition. For the first couple of years, New Smyrna settlers were forced to live in huts with sand floors, but by 1777 the colony boasted 145 houses. Conditions at the colony were so bad that the settlers, who felt imprisoned, led an unsuccessful revolt before their first year was over. By 1777, 964 deaths were recorded at New Smyrna from the roughly 1,400 who came with Turnbull in 1768.[12] To make matters worse, New Smyrna colonists reported that Turnbull refused to honor their contracts after they expired, forcing them to work despite the end of their indentures.[13] Despite their slave-like treatment, Minorcans were not an enslaved work force, nor were they servants. They were a temporary work force of free people—at least from a legal perspective.[14] Regardless of their status, life for Minorcans at New Smyrna was deprived, primitive, and characterized by constant struggle.

As unrest gripped the northern colonies, Parliament was determined to keep Florida under British control. In March 1774, Col. Patrick Tonyn was named governor of East Florida.[15] In 1775, East Florida became a designated loyalist haven for refugees fleeing violence from colonies enveloped in the anti-British movement.[16] The following year, on February 27, 1776, East Florida’s inhabitants drafted an address to the king affirming their loyalty to him. They wrote that they were “deeply deploring and disavowing the present unhappy and unnatural Rebellion, which prevails through most of Your Majesty’s other Colonies on this Continent.” East Florida’s inhabitants also promised to avoid any “connection and Correspondence with, or Support of [the rebels] . . . we shall be always ready, and willing to the utmost of our weak abilities to manifest our Loyalty to Your Majesty’s Person, and a due Submission to Your Majesty’s Government, and the Legislature of Great Britain.”[17] Tonyn held no doubts about the loyalty of East Florida. His did have concerns, however, about the ability of East Florida to defend against attack.[18] As far as Tonyn was concerned, the colony was nearly indefensible.[19]

To counter the colony’s weakness, Tonyn organized a militia battalion made up of loyalist refugees from the northern colonies.[20] “Attested to serve three Years or during the Rebellious Troubles,” they would bolster East Florida’s defenses.[21] Tonyn sought to raise four companies of men from among the people of African descent in the colony, plus two companies from the Saint John’s River and four from St. Augustine.[22] Tonyn considered raising a company of Minorcans as well, but he and Andrew Turnbull were suspicious of the Minorcans’ loyalties to the Crown. In a letter to Lord George Germain, Secretary of State for America in Lord North’s Cabinet, Tonyn stated, “I am credibly informed, that they have invited the Rebels in Georgia, to come to their relief, and deliverance, and have promised their assistance.”[23] Turnbull even expressed his concern in a private letter, saying “there is a good number of them [New Smyrna colonists] at present a little discontented, and I am fully perswaded would Join the Rebels immediately on their landing at Smyrna.”[24] Turnbull was so concerned he requested an additional eight to ten British regulars to bolster the garrison already stationed at New Smyrna.[25] Tonyn complained to Germain about sending additional soldiers to the settlement; after all, soldiers were much needed farther north to defend the Florida-Georgia border.[26] Colonel Robert Bisset, a British officer stationed in East Florida, attested to the indefensibility of New Smyrna which was largely due to the settlement’s lack of arms and ammunition. According to Bisset, the situation in New Smyrna was “very alarming especially with regard to Dr. Turnbull’s people, a great many of whom would certainly Join them [the rebels].” Bisset assured Tonyn that he would go to New Smyrna and arm trustworthy settlers and disarm suspected rebel sympathizers.[27]

Ambitious to tap into the manpower residing in New Smyrna, Tonyn tempted the settlers to join his militia with offers of land, freedom, and protection if they abandoned their lot with Turnbull.[28] Of course, in letters to Germain, Tonyn played innocent against his true intentions of bolstering his militia ranks.[29] In March 1777, a few settlers escaped New Smyrna while Turnbull was away in England, and arrived at St. Augustine seeking an audience with Governor Tonyn to confess their grievances about life under Turnbull at the New Smyrna settlement. What followed was a months-long process of processing complaints issued by the settlers against Turnbull and his overseers. Some of the accusations detailed the horrid sufferings endured by the colonists which included “cruelties and murders.” What followed was a rapid succession of events that ultimately contributed to the demise of New Smyrna. The East Florida courts ruled in favor of Turnbull and ordered the settlers to return to their indentures.[30] In July, 1777, Tonyn told Germain that the New Smyrna settlers were liberated on account of “conditional” and “shocking” circumstances. He informed the secretary of state that small lots of land would be given to families of the freed settlers.[31] In reality, Tonyn disregarded the court’s decision to return the indentured New Smyrna workers back to their master’s plantation, and instead encouraged the colonists to settle in St. Augustine where he assured them that he would protect them. As a result of Tonyn’s murky treatment of the law, the Minorcans left New Smyrna for St. Augustine. During their time in the colony’s capital, they were almost forgotten. Land was never doled out and many were forced to beg in the streets or find sustenance in fishing—they were wholly ignored by Tonyn.[32] Desperate for coin, many joined the East Florida Rangers.[33] Some were dispatched to the Florida-Georgia border where they helped Indians scalp American settlers.[34] Turnbull was furious, charging Tonyn as the reason for his plantation’s collapse.[35] In the end, Tonyn got what he wanted out of Turnbull’s colonists: men for his loyalist militia.

Even after the Minorcan exodus, not all the settlers had left; New Smyrna was still in operation and produce continued to be exported from the plantation.[36] To this day, the city of New Smyrna Beach in Florida stands on the former settlement founded by Turnbull. Turnbull later left Florida after it was ceded to the Spanish and went on to petition a compensation claim that Parliament had offered to former British Florida colonists who had lost land in the Spanish secession. He won 916 pounds. After the evacuation of East Florida, Turnbull moved to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was permitted to remain as a British subject after the former colony officially became a state. He died on March 13, 1792 in Charleston.[37] As for the Minorcans, some fled with the loyalists and resettled in the Bahamas, Dominica, and Europe.[38] Most of them, however, stayed behind, choosing to convert to the Catholic religion and become Spanish subjects.[39]

Although their story is not well-known, the Minorcans lived out the drama that unfolded between East Florida’s leaders during the American Revolution. Put in a precarious situation and far from their native home, some Minorcans served the British during the war, but not out of true loyalty. Most served the Crown out of desperation and to avoid a bitter death in a harsh, war-torn, scarcely populated frontier colony that rested on the far-flung fringes of the British Empire. The reluctance of many Minorcans to evacuate with the British speaks volumes about not only their lack of commitment to the British government, but also the loyalty they had for each other and their community. For many Minorcans, most of what they did, they did together. They endured the brutality of New Smyrna’s overseers together, they petitioned Tonyn against their injustices suffered at Turnbull’s plantation together, most abandoned New Smyrna together to live under Tonyn’s protection, and many remained in Spanish Florida together after the British departure in the 1780s. The rest is history. Minorcan descendants still live in St. Augustine to this day where they continue to represent a large portion of the city’s population.[40]

[1]For further reading on the New Smyrna colony see Carita Doggett Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida (Florida: The Drew Press, 1919); Charles Loch Mowat, East Florida as a British Province, 1763-1784 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1943); Kenneth H. Beeson Jr., Fromajadas and Indigo: The Minorcan Colony in Florida (Charleston: The History Press, 2006); Epaminodas P. Panagopoulos, New Smyrna: An Eighteenth Century Greek Odyssey (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1966); Wilbur Henry Siebert, “Slavery and White Servitude in East Florida, 1726-1776,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 10, no. 1 (July 1931): 3-23.

[2]Mowat, East Florida, 71-72.

[3]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 19.

[5]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 24-28.

[7]William Bartram, Travels Through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws (Philadelphia: James and Johnson, 1791), 142.

[8]Siebert, “Slavery and White Servitude in East Florida, 1726-1776,” 18.

[9]Panagopoulos, New Smyrna, 58, 87.

[10]Beeson Jr., Fromajadas and Indigo, 63.

[11]Panagopoulos, New Smyrna, 85; Beeson Jr., Fromajadas and Indigo, 82-83.

[12]Panagopoulos, New Smyrna, 59, 83, 86, 91-92.

[13]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, May 8, 1777, in The Turnbull Papers (Jacksonville, 1940), 211.

[14]Beeson Jr., Fromajadas and Indigo, 82.

[15]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 106.

[16]Wilbur Henry Siebert, Loyalists in East Florida, 1774-1785, Vol. 1, The Narrative (Reprint, Greenville: Southern Historical Press, 1972), 23-24.

[17]“The humble Address of the Inhabitants of the Providence of East Florida,” February 27, 1776, in The Turnbull Papers, 124.

[18]Jim Piecuch, “Patrick Tonyn: Britain’s Most Effective Revolutionary-Era Royal Governor,” Journal of the American Revolution, March 22, 2018, allthingsliberty.com/2018/03/patrick-tonyn-britains-most-effective-revolutionary-era-royal-governor/#_edn11.

[20]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, August 21, 1776, from The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, transcribed by Todd Braisted, www.royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/eastflmil/eflmillet1.htm.

[21]Patrick Tonyn to Augustine Prevost, December 24, 1777, from The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, transcribed by Todd Braisted, www.royalprovincial.com/military/facts/ofrlet8.htm#:~:text=Other%20Facts%2FRecords%20Tonyn%20to%20Prevost%3A%20St.%20Augustine%2024th,always%20ready%20to%20give%20you%20Sir%20every%20Satisfaction.

[22]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, August 21, 1776.

[23]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, May 8, 1777, in The Turnbull Papers, 211.

[24]Andrew Turnbull to Arthur Gordon, September 1, 1776, in The Turnbull Papers, 157.

[25]Andrew Turnbull to Arthur Gordon, September 1, 1776, in The Turnbull Papers, 157; Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 103.

[26]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, September 8, 1776, in The Turnbull Papers, 159.

[27]Bisset to Patrick Tonyn, September 1, 1776, in The Turnbull Papers, 158.

[28]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 157.

[29]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, May 8, 1777, in The Turnbull Papers, 211-212.

[30]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 157-159, 163.

[31]Patrick Tonyn to George Germain, July 26, 1777, in The Turnbull Papers, 220.

[32]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 164-165.

[33]Andrew Turnbull to Earl of Shelburne, November 10, 1777, in The Turnbull Papers, 221.

[34]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 170.

[35]Andrew Turnbull to Earl of Shelburne, November 10, 1777, in The Turnbull Papers, 221. This aspect of East Florida/New Smyrna history, which I will not go into detail here due to a lack of space, covers a prominent episode in the colony’s histories. The feud between Tonyn and Turnbull was a long, drawn-out battle that often became personal.

[36]Beeson Jr., Fromajadas and Indigo, 83.

[37]Corse, Dr. Andrew Turnbull and The New Smyrna Colony of Florida, 186, 192-194.

[38]Patrick Tonyn to Thomas Townshend (Lord Sydney), April 4, 1785, in The Turnbull Papers, 359.

[39]Patrick Tonyn to Thomas Townshend (Lord Sydney), April 4, 1785, in The Turnbull Papers, 359-360. In June 1784, when Spanish governor de Zespedes arrived in Florida, he promoted the Minorcan priest, Pietro Campo who influenced many Minorcans to remain behind (Corse, 191).

3 Comments

Very interesting and well written.

Thank you, John.

Thank you. Very informative. I have always wondered about Florida and that period in time. My family were already, trying to live in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia at this time. Their true struggles,will never be fully known.