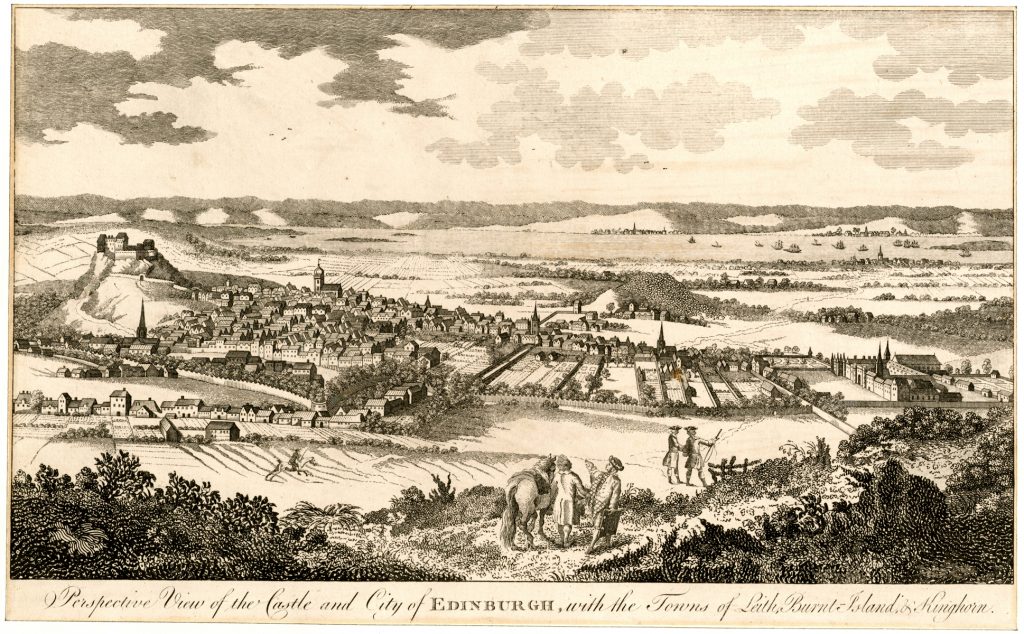

Into a house at 333 High Street in what is now Edinburgh’s “Old Town” was born the strange adventurer Patrick Ferguson on June 4, 1744.[1] The city in that year was still medieval in appearance, its skyline dominated by Edinburgh Castle atop an ancient volcanic bluff. From there, shops and residences cascaded down High Street along the ancient slope’s crest to the city’s eastern end at Hollyrood Palace, built as a royal residence to Scotland’s kings and queens in the sixteenth century, by then claimed for England’s royal family.

Defending this tail of land were ancient walls and gates, along with the man-made Nor Loch to the north and marshland to the south, creating a city contained by her landscape, not unlike Manhattan or Hong Kong. High Street itself was described by the writer Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, as the “most spacious, the longest, and best inhabited Street in Europe.” True, in parts the street was wide enough to accommodate five carriages moving abreast, but with limited geography, the city grew up, not out, some of its tenements reaching as high as twelve stories.

Down the slopes from this central thoroughfare ran a network of twisting streets, extending into a labyrinth network of “wynds,” or alleys, and “closes,” or dead-end courts. A stranger approaching the city, seeing it piled “close and massy, deep and high—a series of towers rising from the palace on the plain to the castle in the air—would have thought it a truly romantic place,” wrote the nineteenth century historian Robert Chambers. On entering High Street from the bottom of the hill, this visitor would’ve seen “much to admire—houses of substantial architecture and lofty proportions, mingled with more lowly, but also more arresting wooden fabrics; a huge and irregular, but venerable Gothic church surmounted by an aerial crown of masonry; finally, an esplanade toward the castle, from which he could have looked abroad upon half a score of counties, upon firth and fell, yea, even to the blue Grampians.”[2]

A feast for the eyes, perhaps, but not the nose. Crammed atop one another in tenements belching smoke, residents regularly dumped garbage and human waste onto the adjacent streets, where it became fodder for roaming livestock—pigs, sheep, chickens, and the occasional cow. No surprise the town was nicknamed not for its majestic countenance, but “Auld Reekie” for its terrible stench.

But there was alchemy in that scent, the reaction of commerce and academics, society and law, agitated in Edinburgh’s confined space by a pair of cultural cataclysms and igniting into the era now known as the “Scottish Enlightenment.” The first of these cataclysms was the Act of Union, the treaty that united the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland into “Great Britain.” Passed by the Scottish Parliament in 1707, the union was controversial in its time because it abolished the Scottish parliament, leaving Scots with only forty-five seats out of 558 in the new British House of Commons. Though Scotland would maintain her separate legal system, and the independence of her burghs, direct control of taxes, duties, and foreign affairs was now ceded to London, four hundred miles to the south.

In the union Scots traditionalists also feared the loss of her cultural heritage and religious independence, ruled over by the Kirk, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Its businessmen feared the loss of international trade. During its deliberation, the Act of Union would lead to riots in Edinburgh’s streets. Yet ultimately these fears would prove to be the unfounded paranoia of change. “In the span of a single generation it [the Act of Union] would transform Scotland from a Third World country into a modern society, and open up a cultural and social revolution,” writes historian Arthur Herman. “Scots ended up with the best of both worlds: peace and order from a strong administrative state, but freedom to develop and innovate without undue interference from those who controlled it.”[3]

But old animosities die hard, and the second tumult affecting eighteenth century Scotland was the Jacobite rising of 1745. The “Forty-five,” as it is known, was an attempt by Charles Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Stuart, the son of James II. The last Roman Catholic monarch of England, Ireland, and Scotland, James II (or James VII, as he was known in Scotland) was deposed in 1688, leading eventually to the coronation of the Hanoverian George I in 1714. (The term Jacobite, or Jacobitism, is derived from the Latin Jacobus, or James, and refers to those who supported the royal claim of James II and his descendants.) With his father exiled in Rome, and the British military distracted by war with Spain, the twenty-three-year-old Charles launched an ill-conceived invasion of the British isle, landing on the Scottish west coast in July 1745.

Though the expeditionary force of French soldiers promised to Charles never arrived, and the pro-Catholic clans of the Scottish Highlands were skeptical of his schemes, Charles’ invasion nevertheless first found improbable success. Marching to Edinburgh, Charles and his Highland army easily pushed aside the opposition of a hastily formed and disorganized Whig militia to capture Edinburgh in September, then swept south into England, marching to within 130 miles of London by December 4.

But with England’s army finally mobilized against him, and his Highland generals’ feet growing cold, Charles abandoned his ill-conceived invasion later that month, retreating to Glasgow on Christmas Day. On April 16, 1746, his dissipated army was defeated within an hour at the Battle of Culloden, leaving the Jacobite cause in ruins. Charles eventually escaped to France, at one point traveling in the disguise of an Irish maidservant, until eventually returning to Rome, where he spent the rest of his life as a corpulent alcoholic.

Often portrayed as a war between Scots and Englishmen, or a religious conflict, the “Forty-five” was, in fact, a cultural war, supported by a traditional landowning class in both countries, whose authority and wealth derived from a rural-based society. In contrast stood the “Whigs,” the name derived from a Scottish term for sour milk, who supported the Act of Union and were resolutely pro-House of Hanover. “Jacobitism reflected a nostalgic yearning for a traditional order . . . It satisfied a deep utopian longing for a perfect society, except that it looked backward, rather than ahead,” writes Herman. “Charles’s supporters could not afford for Scotland to move forward, and so they were prepared to fight and die to topple the existing Whig regime. Scottish Whigs could not afford to go backward, and so they were willing to do anything . . . to keep the Stuarts off the throne.”[4]

The dichotomous relationship between backward and forward, old and new, was alive in the Ferguson household. Patrick Ferguson’s father, James Ferguson, was a talented lawyer, noted for his humanity to “low, friendless creatures” in criminal cases though suspected of Jacobite leanings. Indeed, James Ferguson fits the description of a prototypical Jacobite, not only because he was Episcopalian, and thus deemed suspect by Edinburgh’s Protestant majority, but also because his family owned the Pitfour estate in Buchan, at the far corner of northeast Scotland, making him a part of the landed gentry that tended to support the Jacobite cause. His choice in marriage only contributed to these suspicions: in 1733, he married Anne Murray, the daughter of the Fourth Lord Elibank, a peer of Scotland, as ordained by the King of Scots, and thus also suspected of Jacobite sympathies.

In 1746, James had defended Jacobite prisoners in trials proceeding from the Forty-five, further retarding his legal career.[5] Nevertheless, he was well-liked by his colleagues, noted for his wit, and in 1764, at the advanced age of sixty-four, he was raised to the Bench of the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary, allowing him to assume the title Lord Pitfour, after his family estate which he had inherited in 1734 and steadily improved.

James and Anne had a loving marriage, producing three sons and three daughters that reached adulthood, including Patrick, the second son and fourth child. Their home was a typical Edinburg tenement, located in the Luckenbooths, a portion of High Street facing St. Giles Church, named for its ground-floor lucken, or closed shops, as opposed to the open booths which then lined High Street on both sides.[6] The Ferguson’s occupied four of the tenement’s seven levels—the three immediately above the shop level at the street, and the garret on top, which served as servant’s quarters. In an early edition of Traditions of Edinburgh, Chambers described the home:

A common-stair runs through the whole, at the first landing-place of which we find the lower door of Pitfour’s house . . . The door by which company was admitted, is at the second landing-place . . . The lower flat was appropriated to menial purposes, while the second contained the dining-room and drawing-room, and the upper floor comprised a parlour and a few bedrooms.[7]

Patrick Ferguson’s family status and address placed him at the epicenter of Edinburgh’s Enlightenment. “Only London and Paris could compete with Edinburgh as an intellectual center,” writes Herman, “this was in part because everybody was the neighbor of everyone else.” Patrick’s close neighbors included the philosophers David Hume and Henry Home (Lord Kames), as well as the writer John Home. The philosopher Adam Ferguson was a close family friend, though not a direct relation. And drawn to this intellectual cauldron were such outside luminaries as Benjamin Franklin, poet Robert Burns, and the Aberdeen professor Adam Smith, soon to be famous for publication of The Wealth of Nations. “Edinburgh was like a giant think tank or artist’s colony,” observes Herman, “except that unlike most modern think tanks, this one was not cut off from everyday life. It was in the thick of it.”[8]

Ferguson’s parents participated in the almost nightly outings that characterized this intellectual renaissance, just as often gathering at a local tavern or oyster house as at the home of friends, where dinner parties of the smart and socially connected flowed with copious alcohol. One Edinburgh resident of this period recalled that in the first thirty years of his marriage, he and his wife never spent more than one night a month at home; James and Anne Ferguson would’ve enjoyed (or endured) a similar social calendar.

Yet these settings were not simply social frivolity, for the claret-fueled discussion often turned to serious political and philosophical issues of the day, and if Edinburgh’s social elite were not enjoying a dram in a friend’s home or local tavern, they were doing so at one of the city’s proliferate clubs and societies. James Ferguson was a member of the Select Society, “the central forum of Edinburgh’s republic of letters. A paper or talk presented there received a fairer and more rigorous hearing than it could from any academic or university audience.” According to historian Richard Sher, the Select Society included “virtually every . . . prominent man of letters and taste in the Edinburgh vicinity” including physicians, architects, military officers, merchants, magistrates, and above all, lawyers.[9]

And though young Patrick would not have participated in these adult gatherings during his early years, he would’ve been aware of the culture, society, and philosophical debates swirling around him. One of these debates centered around the “Militia Movement.” Ever since the Forty-five, Scotland’s citizens were prohibited from owning weapons, effectively eliminating any organized local militia. The Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson, an early influence on Patrick, was one of many who argued that a citizen militia was an important way to keep alive traditions of physical courage and martial spirit in a commercial society.

Scotland’s militia movement was closely tied to the concept of “liberty,” which had long been popular in Scots culture but was refined and expanded during the Enlightenment by philosophers Ashley-Anthony Cooper, the third earl of Shaftesbury, and Francis Hutcheson, among others, then passed on to their disciples, including Adam Smith. For Hutcheson, liberty was the crucial element in human behavior: we are born free and equal, and our desire for this natural condition persists through life, despite society’s efforts to oppose it.

At its most basic level, conceptual liberty applies to fundamental rights, including notably the right to own and govern property in a manner its possessor sees fit, without undue interference from others. Yet according to philosophical tradition, these universal rights were not unfettered, permitting the privilege to do, say, or act however one wants. For Hutcheson, and later Smith, the basic right of liberty must be governed by innate moral sense, along with moral obligations to others, which enable humankind to distinguish between the virtuous and the inhumane. The nature of virtue was an inalienable as the nature of liberty, they argued, and society relied on both to function and thrive.[10]

Patrick Ferguson must’ve listened to these arguments as a boy, and later a young man, though his fate was to be a solider, not a philosopher. The second-born male, Patrick would not inherit the family estate, and thus his family early set about finding him a profession. In this, his mother’s brother, James Murray, was an important influence. In 1756, Murray was a lieutenant-colonel in the British army, and Patrick’s family purchased for the twelve-year-old boy an ensigncy in his uncle’s regiment, the 15th Foot.

Though at that time it was not uncommon for a boy as young as twelve to enter the army, the conflict known as the Seven Years’ War (or the French and Indian War, as it was known in America) was brewing, and Patrick was deemed too young for combat. That commission was resigned, its cost refunded, but in 1759 another commission as cornet was purchased for the then fifteen-year-old Patrick Ferguson in the Royal North British Dragoons, known as the “Scots Greys.”

But first his uncle James, now a brigadier general commanding British forces in Quebec following the death of General James Wolfe, arranged for young Patrick to attend the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, in south-east London. At Woolwich, the curriculum focused on engineering and artillery; he also studied fencing, drawing, model-making, French, and mathematics. The academy was a privilege available to few young British Army officers. With few Ferguson papers available for study, we must presume his later aptitudes in fortress design and gunsmithing were cultivated there. Yet according to his biographer M.M. Gilchrist, Patrick often felt lonely in London, regarding the city “as solitary to me as the Highlands.” An anti-Scots prejudice in London fostered by opponents of John Stuart, Lord Bute, the first prime minister from Scotland since the Acts of Union, might have contributed to this sense of isolation, Gilchrist theorizes.[11]

After Woolwich, Patrick’s mother lobbied for Patrick to be returned to Scotland, for he remained a slight and fragile boy, a physical stature he would retain throughout his life; hardly a suitable candidate for war, Anne feared. “Dare I tell you that I was in a horror least he should have been ordered to Germany,” she wrote her brother James.[12]

Yet the Scots Greys were posted to Germany, where young Patrick joined them, though of his service there little is certain. His nineteenth-century biographer, Lyman Draper, reports Ferguson arrived in Germany shortly after the Battle of Minden in 1759 and served in a company of dragoons in June 1760 that helped drive French cavalry and infantry across the Rymel River in disorder. On August 22, 1760, Draper writes, Ferguson’s dragoons similarly took part in the defeat of a French party near Zierenberg, a “brilliant charge” that led to the capture of Zierenberg the following month.[13]

But Draper provides no reference for these accounts, and their dates aren’t supported by the correspondence of Anne Ferguson provided by Gilchrist. Patrick Ferguson’s most famous alleged exploit from the Seven Year’s War is reported by Adam Ferguson, who later wrote a brief biography of Patrick, though also vaguely substantiated. According to this account, Ferguson was on a mounted patrol in Germany with another young officer “a few miles in front of the army” when they “fell in with a party of the enemies’ hussars, and finding it necessary to retire, were pursued.” As they raced away, Ferguson dropped one of his pistols as he passed a ditch, “but thinking it improper for an officer to return to camp with the loss of any of his arms, he re-leaped the ditch in the face of the enemy, and recovered his pistol.” Impressed by Ferguson’s bravery, the hussars (a Polish or Hungarian term for light cavalry soldier) halted their pursuit, allowing him to repass the ditch and return to the British lines.[14]

What is certain is that Patrick Ferguson’s health failed in Germany’s combat conditions, perhaps a victim of synovial tuberculosis. Though rare today, especially in the western world, synovial tuberculosis, or tuberculous arthritis, is a form of the disease that spreads to and infects the joints, or occasionally, the spine. In Ferguson’s case, it likely began as an untreated case of lung tuberculosis, for his mother reports of his consumptive complaints, with the infection eventually spreading to a knee.

Unable to serve with his regiment, he spent six months bedridden in Osnabrück, Germany, under the care of British army physicians, before he was returned home to recover. His mother was downcast. “I much doubt if he shall recover the constitution that was meant to him by nature,” she lamented. Ferguson attempted to remain optimistic, though the illness would lead to a six-year convalescence that shook the young man’s confidence. “As to his soul, illness had struck him at a vulnerable age,” writes Gilchrist of the eighteen-year-old Ferguson. “He was acutely aware of his weaknesses.”[15]

At least he was back in Scotland, among friends and family, where he was well enough to participate in Edinburgh’s active social and intellectual life. Like the Select Society, the Poker Club was one of those Edinburgh institutions that mixed social conviviality with discussion of important political and philosophical issues of the day. Founded in 1762, the Poker Club was initially named the “Militia Club,” formed to discuss and promote Scotland’s militia movement, though the name was changed to be more enigmatic to the general public. Among the society’s founders was the philosopher Adam Ferguson, who knew Patrick well during this period, and Patrick’s eldest brother Jamie, named after James Murray, Patrick’s uncle and patron.

“Why did the Scottish Enlightenment embrace the militia cause so strongly?” asks Herman. The disgraceful performance of Edinburgh’s Whig militia during the Forty-five had something to do with it, though in typical Scottish Enlightenment fashion, the issue of home defense became a philosophical one. “When liberty is threatened, can anyone expect young men raised in a cushy commercial environment to risk their lives on the battlefield . . . Obviously not, unless they have help . . . cultural help, something that taught them self-sacrifice, discipline, and loyalty, and gave them confidence in their own physical powers and those of their weapons. This, [Adam] Ferguson and the rest believed, militia training could do.”[16]

Given Patrick Ferguson’s social connections to the Poker Club, he likely participated in some of their meetings, for Adam Ferguson reports Patrick “entered warmly into the question,” of the militia movement. “He saw no difficulty in combining the character of a soldier with that of a citizen . . . some of the ablest and most intelligent publications which appeared in the public prints of the time, were of his writing,” though as a serving army officer, these letters would have been published under a pseudonym.[17]

Many of Ferguson’s biographers skim over the next six years of his life. His biography in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes only, “after one campaign in Germany he was struck down in sickness which kept him from service between 1762 and 1768,”[18] as does the biographical sketch composed by Adam Ferguson.

But Scots biographer M.M. Gilchrist was able to access family correspondence through the National Archives of Scotland and the National Register of Scotland (now consolidated at the National Records of Scotland, or NRS), and it is from her account upon which much of the following information is based.[19]

Though still recovering, Ferguson obviously embraced his return to Edinburgh society, perhaps a bit too much. In February 1763, he was sent to the family estate Pitfour at Buchan, at the far corner of northeast Scotland. From there he wrote, “when I recollected my motives for leaving Edinburgh I thought I had fallen out of the frying pan in to the fire every night drinking till two next morning & then Sleeping till two in the afternoon . . . Rather as post there I chose to post to Pitfour, where I hope my bones (flesh I have none) will rest in peace.”[20]

The bucolic pace of Pitfour suited him, and by May 1763, his brother Jamie reported after a visit that Patrick was in good health and good spirits. Good enough for Patrick to rejoin his unit, the Scots Greys, in August at Kelso, a market town on the Scottish border, and accompanying them to nearby Coldstream later that fall.

In eighteenth-century United Kingdom, there was no police force. Army units not in foreign service were often posted in provincial cities and communities, acting as a security detail. Though Ferguson’s duty was light, the cold weather disagreed with his health, once more troubling his weak leg, and he was probably home again at the beginning of 1764, since records indicate that year he was inducted into the Burgess and Guild Brethren of Edinburgh, yet another Edinburgh society, of which his father was also a member.

His health on the mend, though far from restored, Patrick rejoined his regiment later that year, eventually posting in Manchester, where the wealth of northern England’s Industrial Revolution impressed him, though he soon grew homesick. “There is not one man who has the Spirit of a Gentlemen,” he complained of the Mancunian nouveau rich, “and their women deal eternally in Scandal & live by defamation.” Garrison duty was mostly uneventful, though in one noticeable incident, Patrick resisted pressure to hang some local rioters without due process of law. “It says much of Patrick’s integrity and courage that . . . he withstood the local gentry’s demands for executions,” writes Gilchrist, who observes Patrick was only twenty at the time. “Enforcing the law was one matter; bending it to private interests was another. He proved himself his father’s son.”[21]

After a plan for James Murray to obtain a captain’s commission for him in Quebec fell through, Ferguson grew increasingly frustrated with the stasis of his military career. “Nothing but the terrors of hanging, or the bodily Danger of fifty Cannon shot a day will rouse me from this long lethargy with which I’ve been overwhelm’d these three Years; I wish therefore it wou’d please his Majesty, either to allow me money to hire a nurse to keep me constantly asleep, or hang me, or send me abroad.”[22]

A posting abroad increasingly appeared to be Patrick’s only chance of promotion, though he continued home guard duty with the Scots Greys, first posting in Coventry, then Worcester, England. In September 1765, Patrick went on leave, visiting friends and family in Scotland and spending time at the London home of his uncle, Lord Elibank, but by March 1766 he was back with the Greys, experiencing frustrations anew when a younger officer was promoted to lieutenant. Patrick himself was still only a cornet, the lowest commissioned rank, though he was by now senior to at least half the lieutenants in the regiment.[23]

Frustrated with yet another domestic posting, Patrick requested leave again that fall, this time traveling to France, where he intended to enroll in the military academy at Angers but instead spent his time enjoying Paris, finishing his sojourn with a tour of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Calais. Returning home in early in 1767, Patrick again lamented his moribund military career, as in this letter to his sister Betty: “You will say I’m very young, that of course I have time enough & cannot have been very unlucky . . . as to my luck as we can only judge comparatively the list of our Army will at one glance show you I have been the most unlucky man in it, as I am by three years the Oldest Cornet & older than three fourths of the Lieutenants.”[24]

His return to the Greys found him on home guard duty again, which he endured for the rest of 1767, though 1768 finally brought him an opportunity: When a captain’s commission became available in the 70th Regiment, serving under his cousin Lt.-Col. Alexander Johnstone, Ferguson seized his chance, though the posting was in the West Indies, where heat and fever would test his constitution. In December 1768, the newly commissioned Capt. Patrick Ferguson sailed for Grenada with his new company.

In Grenada, Patrick was stationed at Fort Royal, present-day St. George’s, though he was soon reassigned to Tobago. Johnstone now owned a plantation in Grenada which had proved a profitable venture, and in Tobago, Patrick followed suit, acquiring an estate on behalf of his family in Castara. There were two slave insurrections in Tobago during Patrick’s posting there, though there is no correspondence to suggest Patrick saw any action in them. By 1771, he was ill again, probably a flareup of his tuberculous arthritis, and by the fall of 1772 Patrick was headed home, again a semi-invalid, again his military career in disarray.[25]

He returned to find his beloved Edinburgh much changed. In 1745, the year after Patrick was born, the ancient city’s population was a manageable 40,000 people. But by the 1760s, the population had almost doubled, mostly crowded inside the same medieval urban space. City leaders realized something must be done. In Edinburgh fashion, they sponsored a competition to develop a new residential neighborhood above the North Loch, which would become known as “New Town.” Under the plans of contest winner James Craig, a twenty-one-year-old mason, the development was started in 1768. New Town began slowly, but in 1772, the year of Patrick’s return from the West Indies, a bridge connecting it with Patrick’s beloved “Old Town” was completed, accelerating an urban diaspora that would leave the city much transformed, eventually turning Old Town into an urban ghetto, at least for a time, though the Ferguson family remained true to their Old Town roots. Patrick’s eldest brother Jamie would maintain the family’s High Street address until his death in 1820, long after neighborhood had become unfashionable.[26]

The sensitive and intelligent Patrick must have perceived this fundamental shift in his beloved home, just as he would’ve been aware of the escalating tensions in the American colonies. And as usual, he couldn’t stay long. By 1773, he was back in London, helping the 70th Foot recruit and once more seeking meaningful deployment in the British Army. His opportunity would come, though not for three years. As usual, he would spend the interim obsessed over issues of rank and status, even as his health remained fragile. But his mind was sharp and invigorated, and in Scottish Enlightenment fashion, it was to it he would turn to craft the greatest opportunity of his troubled career in the form of the Ferguson Rifle.[27]

[1]Ferguson’s biographer, M.M. Gilchrist, notes this was the date celebrated as his birthday after the Gregorian calendar was adopted in 1752. Under the Julian Calendar, his birthday was May 24.

[2]Robert Chambers, Traditions of Edinburgh (London and Edinburgh: W&R Chambers, 1869), 11-12.

[3]Arthur Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe’s Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything in It(New York: Crown Publishers, 2001), 54, 59.

[5]Chambers, Traditions of Edinburgh, 143.

[7]Quoted from M.M. Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson: A Man of Some Genius (Edinburgh: NMS Publishing, 2003), 4.

[8]Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World, 190.

[9]Ibid., 193. The Richard Sher quote is taken from his Church and University in the Scottish Enlightenment (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985), which Herman calls “the indispensable guide to the intellectual milieu of Edinburgh in the second half of the eighteenth century.”

[10]Except where otherwise noted, this portrait of Edinburgh and the Scottish Enlightenment is heavily indebted to Herman’s How the Scots Invented the Modern Word. James Buchan’s Crowded With Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment; Edinburgh’s Moment of the Mind (New York: HarperCollins, 2003) was also an important reference.

[11]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 5-7.

[12]Anne Ferguson to James Murray, quoted in Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 7.

[13]Lyman C. Draper, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events Which Led To It (Cincinnati: Peter G. Thomson, Publisher, 1881), 49.

[14]Adam Ferguson, Biographical Sketch, or Memoir of Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Ferguson: Originally Intended for the British Encyclopaedia (Edinburgh: Printed by John Moir, 1817), 8-9.

[15]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 8. The quote from Anne Murray Ferguson is not attributed by Gilchrist.

[16]Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World, 224.

[17]Ferguson, Biographical Sketch of Patrick Ferguson, 10.

[18]D.W. Bailey, “Ferguson, Patrick,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (September 22, 2005), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/9323.

[19]I am deeply indebted to M.M. Gilchrist for this exploration of Patrick Ferguson’s life. Aside from hers, there is no comprehensive biography of Ferguson’s life, perhaps because his family papers remain in Scotland, while his historic significance, thanks to his role in the American Revolution, is primarily limited to the United States. Sadly, a trip to Scotland’s National Records, where family papers are housed, was not in the research budget for this article, making Gilchrist’s biography indispensable. All subsequent Ferguson quotes are from Gilchrist.

[20]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 9.

[24]Patrick Ferguson to Elizabeth (Betty) Scrymgeour-Wedderburn, née Ferguson, quoted in Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 16.

2 Comments

I am so happy to see this article, and I am also glad that Ms. Gilchrist is being given recognition for her tireless work to bring Ferguson to the fore of this period’s history. Some years ago, she visited me in the Southeast US, and I took her to many Revwar southern battlefields. The excellent park at King’s Mountain was a particular favorite for us both. She was a delightful and fascinating companion on these treks, and I learned so much from her. Gilchrist is to be commended for her persistence and scholarship, unearthing information in Scotland and here in the US. Beyond her scholarship, she also possess a sense of humor and creativity that always brought these characters to life, and Ferguson certainly deserves to be studied.

Hi Holley. Glad you liked the article. Yes, the Gilchrist biography was really so helpful and influential. Someday I hope to access the Ferguson archives myself, but for the time being her biography is the best reference resource I’ve found!