Richard Peters’ letter of October 19, 1781, to Gen. George Washington mentioned two missions to obtain copies of certain British naval signals and convey them to French Adm. Francois Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse. These signals have been discussed in numerous books and articles on Revolutionary War clandestine activities. During the five-plus years he was associated with the Board of War, Peters authored three-fourths of the extant letters from that body to Washington of which this one alone is both personal and particularly enthusiastic. Peters was clearly pleased with what he had accomplished and convinced of the importance of the signals. The letter contains numerous clues as to the circumstances of these missions and accordingly is quoted here with the addition of bold font where the two missions are mentioned:

By a Channell of Intelligence I have opened I can procure Access to Rivington’s Printing Office where there is a Person ready to furnish any important Papers as Intelligence! But the Person to bring it is the one I have employed & he in N. York will trust no other. I mention this to your Excellency that if you can think of any material Use to be made of this you will please to take Advantage of it thro’ me as it is confined to my Knowledge only which is the Reason of my personal Address to you. I some Time ago procured a Copy of the British Signals for their Fleet & gave them to the Minister of France to transmit to Compte de Grasse.I had again sent in the Person employed on the former occasion & he has brought out some addition[al] Signals & among them those for the Troops now embarked on Boa[rd] the Fleet on their present Enterprize to the Chesapeak to proceed in which they had fallen down to the Hook yesterday Morning . . . I have thought the Knowledge of these Signals to be so important that I have prevailed on Capt. McLean to carry them to Compte de Grasse with a Letter from the Minister to the Compte in which he is requested to transmit them if necessary by Capt. McLean to your Excellency. The Signals have been reprinted with no Alterations but the Change of the Name of Arbuthnot for Graves. The written Part was copied from the original given to be reprinted.

Should your Excellency have thought proper to interfere in Capt. McLean’s personal Affairs about which I some time ago troubled you he will bear anything you may be pleased to write on the Subject.[1]

The first mission had taken place “some time ago,” a phrase Peters used again in the second paragraph to describe a letter he wrote on October 2, so the first mission probably took place during September 1781, a period that is confirmed by events to be described. The second mission had just ended when this letter was written, on the day Lt. Gen. Charles, Second Earl Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown; it will be seen to have originated the second week of October. The sense of this letter, confirmed by Washington’s October 27 response to it, is that it provided unexpected news to the general. Since Peters had last seen Washington during the latter’s August 30-September 4 Philadelphia visit on his way to Virginia, the first mission must have taken place after that period.

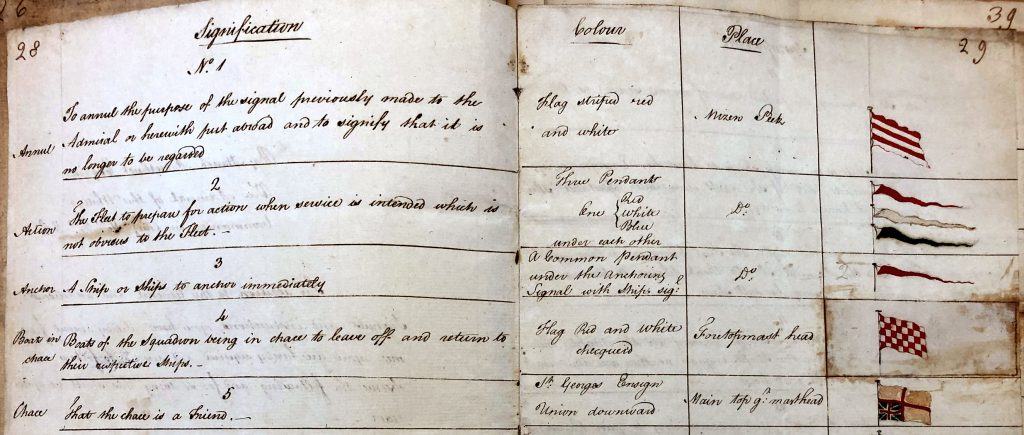

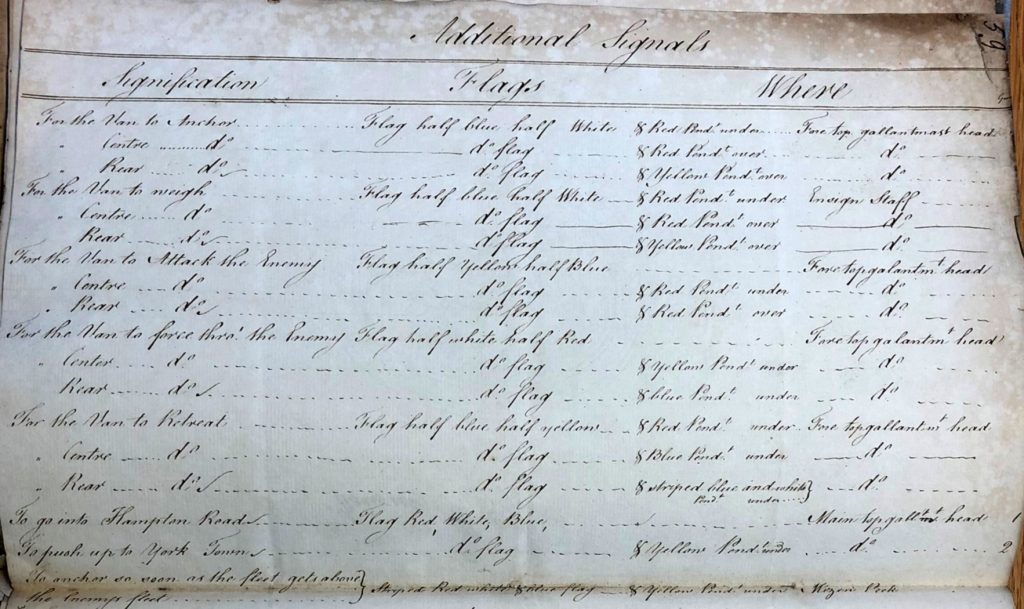

British Naval Signals

The “British signals for their fleet” that Peters’ agent obtained require description that will clarify portions of his letter and the documents acquired. These signals communicated naval tactics between ships in a fleet; signals books typically consisted of a number of specified actions followed by the flag(s) and where flown on the ship to indicate each action. For example, to send the signal “the fleet to wear and come to sail on the other tack, still preserving the line,” one would fly the “Union Flag with a pendant chequered blue and yellow under it” at the Fore and Mizzen Topmast heads.[2] Before 1799 the Royal Navy did not possess a standardized set of such signals; instead, the admiral commanding at each station had the authority to issue his own set of signals to be used by all vessels under his command. The commanders of the British North America Station relevant to this article and the signals they issued were as follows:

- Adm. Marriott Arbuthnot arrived at New York on August 25, 1779, when he issued his own version of Admiralty Signals and Instructions in Addition to the General Printed Sailing and Fighting Instructions (Signals and Instructions). In 1781 Arbuthnot supplemented those with a folio titled Additional Signals for the North American Station.[3]

- Arbuthnot left the North American Station in July 1781 before the arrival of his replacement Adm. Robert Digby. Arbuthnot therefore handed over command to Adm. Thomas Graves as interim commander. On July 6, 1781, Graves reissued Arbuthnot’s Signals and Instructions, with the order that they were to be used until further notice. He also reissued several additional instructions, originally issued by Arbuthnot, with the same order. These were in effect when the British and French fleets met in the Battle of the Capes on September 5, 1781.

- Adm. Robert Digby arrived at New York on September 24 during the period when Graves and Sir Henry Clinton were organizing an expedition to relieve Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. Rather than change station commanders at that critical time Digby agreed to serve under Graves during the expedition. Therefore, from late September until it returned to New York from the unsuccessful Cornwallis relief expedition, the British fleet remained under the command of Graves, although de Grasse expected it to be commanded by Digby.[4]

- During the Battle of the Capes signals confusion between Graves and his admirals was one of the causes of poor British performance. Graves’ actions to prevent similar confusion during the Cornwallis relief expedition included the October 15 issue of a single sheet containing fourteen aggressive signals including specific signals for attacking, forcing their way through, “to go into Hampton Road,” “to push up to York Town,” and “to anchor as soon as the fleet gets above the enemy’s fleet.” He issued additional signals on October 16 and 18 but only those of October 15 contained commands geographically-specific to the relief expedition and must have been the signals mentioned in Peters’ letter as “those for the Troops now embarked on Boa[rd] the Fleet on their present Enterprize to the Chesapeak.”[5] That was later confirmed by Washington’s description of them as requiring “desperate naval combat.”[6]

The surviving copy of Graves’ signals book consists of twenty-four printed pages containing seventy-five signals and instructions, twenty-four manuscript pages containing thirty-nine additional signals, and several manuscript sheets of signals issued at various times including those issued October 15-18.[7] The King’s Printer in New York, James Rivington, supplied the fleet with printed versions of these signals; these were needed because of the large temporary addition to Graves’ fleet of a squadron from the West Indies Station where Adm. George Brydges Rodney used a different set of signals. Graves learned on August 16 that such reinforcements, of an unspecified size, were being dispatched.[8]

Before attempting to determine which signals were obtained during the two missions mentioned by Peters, his role as the mission instigator has to be explored.

The Role of Richard Peters

Richard Peters was an unlikely “spymaster” for the naval signals missions. A respected Philadelphia attorney, he had served for a period as Register of the Pennsylvania Vice-Admiralty Court and was the only person to hold a position on the Continental Board of War for its entire existence, serving first as secretary and then as commissioner. By 1781 Peters was often the only commissioner on the Board who was active and in late November he turned the Board’s affairs over to the first Secretary of War, Gen. Benjamin Lincoln. The Vice-Admiralty Court had jurisdiction over merchant shipping affairs while the Board of War had responsibility only for Continental Army affairs so Peters had no experience with naval affairs such as signals books. To determine what motivated him to pursue their acquisition we must trace his actions through this period.[9]

In August 1781 Congress directed Peters, representing the Board of War, along with Robert Morris, Continental Finance Minister, to meet with General Washington to discuss campaign plans for 1782. The two Philadelphians met with Washington at his Dobbs Ferry, New York headquarters from August 11 to 18. Washington had been aware since May that de Grasse planned to bring a portion of his fleet from the West Indies to North America but did not know where, when or in what strength that fleet would arrive. On August 14 he received word from de Grasse via Lt. Gen. Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau that the French fleet would be in the Chesapeake Bay in late summer to cooperate with the Allied Army and shared that information with Peters and Morris. On August 17 Gen. Henry Knox gave Peters a list of ordnance and supplies that the army needed to acquire when it passed through Philadelphia two weeks later en route to Virginia.[10]

Peters and Morris returned to Philadelphia on August 20 and Peters later recalled that he “set to work most industriously” to ensure that munitions were available when Washington, followed by the Continental Army, arrived at Philadelphia. Peters and his colleagues were thus fully engaged following his return from New York. Washington was in Philadelphia from August 30 until September 4 and undoubtedly conferred with the Board of War during this period.[11]

As we have seen Graves learned on August 16 that he was going to receive a reinforcement from the West Indies and he immediately commissioned the printing of additional copies of his signals for use by its captains. Accordingly on August 22 printer James Rivington included in his Royal Gazette the initial advertisement of those signals:

To the Gentlemen of the Royal Navy,

SIGNAL BOOKS, also

States and Condition of his Majesty’s

Ships, agreeably to the form preferred

by Admiral Graves.

Enquire of the Printer.[12]

This advertisement appeared in the biweekly Royal Gazette almost continuously through October 17. Based on the reprinting of other Royal Gazette items in Philadelphia newspapers the New York newspaper generally made its way to Philadelphia within five or six days of issue, so Peters would have first seen this advertisement about August 27. By the time Washington departed Philadelphia for Virginia on September 4, the same advertisement had appeared in the Royal Gazette twice more. We can only speculate that this advertisement ignited Peters’ interest in obtaining the British naval signals books. Since he knew that de Grasse was soon coming to the Chesapeake Bay he assumed that the advertised British signals books would provide information useful to the French fleet. Once the Continental army collected the ordnance awaiting it in Philadelphia and marched south, the demands on Peters’ time decreased dramatically allowing him to consider who could slip into New York to obtain the naval signals.

The First Mission

We reasoned earlier that the first mission took place in September and showed that it was probably not initiated until after September 4. Once Peters decided to attempt to obtain a copy of the advertised signals, he had to find a person, whom for convenience we will call the Agent, to travel from Philadelphia to New York, contact the printer to obtain the signals, and bring them to Philadelphia. Peters recruited a person who, according to his letter to Washington, trusted only him. That person’s desire for anonymity was so great that Peters declined to name him when writing about the second mission twenty-three years later and he remains anonymous today.[13] The Agent contacted “a Person” in Rivington’s Printing Office who agreed to furnish the desired signals as well as “any important Papers as Intelligence” in the future. That person might have been James Rivington as some believe but might just as well have been one of his clerks or other employees who was pro-American.[14] Assuming Peters found his Agent soon after he conceived the idea for the mission, that person would have reached New York in mid-September.

Peters’ mention of the second mission says that he “again sent in” the Agent, suggesting that the first mission did not produce the signals book he expected. Later in the letter and somewhat out of context he stated, “the Signals have been reprinted with no Alterations but the Change of the Name of Arbuthnot for Graves.” Assuming the latter statement applies to one of the documents obtained during the second mission leads to the conclusion that the signals book obtained during the first mission was the one issued by Arbuthnot. That is a reasonable conclusion because Graves likely took all of the signals books Rivington had printed by September 1 when the fleet departed New York for Virginia, to distribute to the fourteen-ship squadron anchored off Sandy Hook that had arrived from the West Indies three days earlier.[15] Accordingly, the printing office supplied the Agent with the Arbuthnot signals book along with the suggestion that he return several weeks later to obtain the current (whether Graves’ or Digby’s) signals book.

Presumably, the Agent returned to Philadelphia as soon as he obtained the Arbuthnot signals book, placing it in Peters’ hands in late September. By the latter’s account he took it to Chevalier Anne-Cesar de La Luzerne, the French Minister to the United States, also located in Philadelphia, to forward to de Grasse. La Luzerne’s letter transmitting the signals book to de Grasse has not been found but may have been one of those included in his express to the admiral of September 26.[16] In any event this signals book was probably in de Grasse’s hands around the first of October.

The Second Mission

The second mission encompassed two objectives, monitoring British fleet status, and obtaining the current signals book, and added a participant, Capt. Allen McLane. After September 20 when the British fleet had returned to New York following the Battle of the Capes, American observers reported that the British were repairing battle damage as rapidly as possible in order to mount an expedition to relieve Cornwallis. Washington had his own observer, Gen. David Forman, in place near Sandy Hook, New Jersey, reporting British fleet status directly to him throughout the Yorktown Campaign, but the Board of War in Philadelphia had no such source.[17] Peters soon found one in Captain McLane. That officer had seen extensive service in the Continental Army but had resigned earlier in 1781. In June McLane joined the privateer Congress on a cruise from Philadelphia to the Caribbean, returning to that city on September 18.[18]Later that month he met with the Board of War to discuss rejoining the Army, resulting in Peters’ October 2 letter to Washington that suggested a position. While awaiting Washington’s response Peters engaged McLane to go to Sandy Hook, observe British fleet status, and report it to the Board of War. McLane probably embarked on this mission soon after October 2.[19]

About October 10 Peters “again sent [the Agent] in” to New York to obtain the current naval signals book, presumably with instructions to cooperate with McLane in delivering it to Peters. This presumption is based on Peters’ statement in an 1804 letter to McLane that “I sent you into Jersey, for purposes you must recollect. Among others I obtained, thro’ your assistance, & by a Person I sent into New York, the Signals of the British Fleet.”[20] The October 10 estimate is based on the mention in Peters’ October 19 letter that among the signals obtained were those specific to the relief expedition, consisting of the sheet dated October 15. Graves sent that sheet to Rivington to print (not “reprint” as the letter reads) shortly before the fleet sailed, and Rivington’s contact allowed the Agent to “copy [it] from the original.” That had to happen about October 16 in order for the acquired signals to have reached Philadelphia on October 19. The Agent also obtained the Graves signals book that is characterized accurately in Peters’ letter. He probably recognized British intentions inherent in the October 15 signals; McLane, who knew the geography of Chesapeake Bay from previous service, certainly did. That knowledge spurred them to return to Philadelphia with haste; Peters mentioned the position of the fleet “yesterday morning” so McLane, and perhaps the Agent, covered something over eighty miles from Sandy Hook to Philadelphia in two days.

Peters understood the October 15 signals to indicate a degree of British determination, or as a noted naval scholar wrote, a willingness “to take risks which had seemed unjustified six weeks earlier,” about which de Grasse should be informed.[21] He quickly obtained a transmittal letter to de Grasse from La Luzerne and engaged McLane to deliver the signals to the admiral. McLane rode to Head of Elk, Maryland on September 20 where he arranged passage with Capt. John Valliant who was about to depart for Yorktown in the sloop Polly. The British fleet had sailed from Sandy Hook the evening of October 19 so Captain Valliant’s vessel was in a virtual race with it to the Virginia capes. On October 26 Valliant arrived at the French flagship Ville de Paris where McLane handed the British signals to de Grasse before sailing to Yorktown to deliver Peters’ letter to Washington.[22] French lookouts sighted the British fleet off Cape Charles the next morning but Graves had already learned of Cornwallis’s surrender and had no intention of risking his vessels in a futile attack on the French fleet. The British fleet departed October 30 for New York.[23]

Value of the Signals

Peters, the Agent, McLane and numerous others had expended significant effort and some had been at no small risk in obtaining these British naval signals and, for the second mission, delivering them to de Grasse, so it is appropriate to consider what value the signals provided. The disappointing answer is, in a word, minimal. The Battle of the Capes took place on September 5, well before the signals book from the first mission reached de Grasse around October 1. The admiral sent that book to Rochambeau on October 26 with a request that it be returned to La Luzerne but without further comment.[24] He had sufficient time to copy and translate it but there was no reason he should have done so since Arbuthnot no longer commanded in North America, and Rodney commanded in the West Indies where de Grasse was bound. The admiral sent the second set of signals to Washington the day after he received them with this message: “I have the honor to address to Your Excellency a cahier of signals which have been addressed to me by the Chevalier de La Luzerne. I took notice of them and before sending them back, I thought I had to pass them on to you. Please read them and have them copied, if you think it necessary.”[25] We cannot determine whether De Grasse’s seeming lack of interest in the second set of signals was because he recognized most of them were identical to the first set or because he knew they would not be useful in the West Indies. The admiral also had little concern about a determined British attack because of his significant numerical superiority in ships of the line and strong defensive position inside the capes.[26] It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that knowing the enemy’s naval signals was not as important to de Grasse as Peters had expected.

[1]Richard Peters to George Washington, October 19, 1781, Founders Online.

[2]Signals and Instructions in Addition to the General Sailing and Fighting Instructions, KEI/S/8, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK (NMM), 19 (Signal IV).

[3]Copies of Arbuthnot’s signals book survive in NM 83 and NM 92, Admiralty Library, Royal Navy Command Secretariat, Portsmouth, UK.

[4]De Grasse to Rochambeau, September 24, 1781, Henri Doniol, Histoire de la Participation de la France

à l’Etablissement des Etates-Unis d’Amerique (Paris: Alphonse Picard, 1892), 5: 544.

[5]Julian S. Corbett, Signals & Instructions 1776-1794 (Port Talbot, UK: Lewis Reprints Limited, 1971), 17; Brian Tunstall, Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail: The Evolution of Fighting Tactics 1650-1815 (Edison, NJ: Wellfleet Press, 2001), 7, 79, 158, 172-177, 227-231.

[6]Washington to de Grasse, October 28, 1781, Founders Online.

[7]NMM KEI/S/8. The Graves’ documents mentioned in the text have been gathered in a single modern binding that measures twenty-one centimeters by thirty-five centimeters.

[8]The Graves Papers and Other Documents Relating to the Naval Operations of the Yorktown Campaign, French Ensor Chadwick, ed. (New York: Naval History Society, 1916), lxv-lxvi.

[9]Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, entry for Richard Peters,bioguideretro.congress.gov/Home/MemberDetails?memIndex=P000255; Carl Ubbelohde, The Vice-Admiralty Courts and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960), 152-153; Kenneth Schaffel, “The American Board of War, 1776-1781,” Military Affairs, October 1986, 188.

[10]The Papers of Robert Morris 1781-1784 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1975), E. James Ferguson, ed., 2: 50-55, 74, 80; Henry Knox to Board of War, August 17, 1781, GLC02437.01137, Henry Knox Papers, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, New York.

[11]Henry Simpson, The Lives of Eminent Philadelphians, Now Deceased collected from Original and Authentic Sources (Philadelphia: William Brotherhead, 1859), 708.

[12]Royal Gazette (New York), August 22, 1781. The same advertisement appears in sixteen issues of that newspaper between August 22 and October 17, 1781, with the addition of “Slop Books” from September 22 onward.

[13]Peters to Allen McLane, April 26, 1804, Allen McLane Papers, New York Historical Society (McLane Papers).

[14]Todd Andrlik, “James Rivington: King’s Printer and Patriot Spy?” Journal of the American Revolution, March 3, 2014. For an alternate opinion and identification of several of Rivington’s employees see Leroy Hewlett, “James Rivington, Loyalist Printer, Publisher, and Bookseller of the American Revolution, 1724-1802; A Biographical-Bibliographical Study,” PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan, 1958, 172, 178-186.

[15]Signals books were being issued to ships as late as September 5, the day of battle, according to Kenneth Breen, “Graves and Hood at the Chesapeake,” Mariner’s Mirror 66 (February 1980), 61.

[16]La Luzerne to Washington, September 26, 1781, Founders Online.

[17]Forman’s eighteen letters to Washington for the period July 23-October 19, 1781, are on Founders Online.

[18]Kim Burdick, “Allen McLane: A Case Study in History and Folklore,” Journal of the American Revolution, October 15, 2014; Washington to McLane, December 31, 1781, FOL; Thomas Clark, Naval History of the United States in two volumes (Philadelphia: M. Carey, 2nd edition, 1814), 1: 11, 125-127; Charles Stirling to Graves, September 23, 1781, The London Gazette, December 15, 1781, 6; The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), September 19, 1781.

[19]Peters to Washington, October 2, 1781, Founders Online; McLane statement of service, McLane Papers.

[20]Peters to McLane, April 26, 1804, McLane Papers. McLane’s statement, also in the McLane Papers, that “he was stationed by the Board of War near Sandy hook to correspond with R of New York received the signals for the British fleet out of New York” is generally consistent with Peters’ letter but omits mention of the Agent as does a second similar statement in the same papers.

[21]Tunstall, Naval Warfare, 177.

[22]“Capt. McLane’s certificate in his [Capt. Valliant’s] favor,” October 28, 1781, Miscellaneous Numbered Record #22973 and “Certificate respecting Captain Valliant,” November 22, 1781, Miscellaneous Numbered Record #22972, U.S. Revolutionary War Miscellaneous Records (Manuscript File), 1775-1790s, Records Pertaining to Continental Army Staff Departments, Record Group 93, National Archives Publication M859.

[23]“Journal de la navigation de l’Armee aux orders de M[onsieu]r le Comte de Grasse Lieutenant General,” Microfilm MAR/B/4/185, Archives Nationales de Paris, 94; Chadwick, Graves Papers, 137-138; Captain’s Logbook, HMS Prince William, ADM 51/740, UK National Archives, London.

[24]De Grasse to Rochambeau, October 26, 1781, Doniol, Histoire de la Participation de la France, 5:581-582.

[25]De Grasse to Washington, October 27, 1781, Founders Online.

[26]De Grasse to Washington, October 29, 1781, Founders Online.

2 Comments

William, a very thought provoking article, adding yet more confusion to who was the “spy” in the print shop. However it does help explain why McLane was involved outside the Culper network. But the mystery continues.

William, Thank you for clarifying these details. Excellent research, appreciate your efforts in sharing this important information.