James Lovell, delegate from Massachusetts to the Second Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress from 1777 to 1782, the only member of Congress to be continuously present during those years,[1] is known for being the Secretary for the Committee for Foreign Affairs; for his expertise in cryptography, earning him Edmund Burnett’s description of “decipherer extraordinary to Congress;”[2] and for his remarks critical of Gen. George Washington, primarily in the fall of 1777. Concerned about the success of the army, fearful of the potential devastation of defeats such as Brandywine and Germantown, he wrote to his friend Joseph Trumbull in late November 1777, saying, “Our affairs are Fabiused into a confused situation, but yet by no means into a ruined one.”[3] James Lovell was indeed critical, both by nature and by training, but a sharp and discerning eye was needed as the members of Congress fought a hard fight to fund a war without taxes, maintain the military, and hold together a collection of states with varying and disparate interests.

A school teacher who contributed to the formation of government led by the will of the people in the United States, James Lovell was born in 1737 to Master John Lovell of the Boston Latin School and his wife Abigail. One of thirteen children, James proved an apt student under his father’s strict and devoted tutelage. He earned a scholarship to Harvard, partly at least for his ability to deliver the memorized recitations that assessed a pupil’s progress, as reviewed by the Boston selectmen. Along with James, Master Lovell taught many who became prominent leaders of the Revolutionary movement, including Samuel Adams, James Bowdoin, John Hancock, Henry Knox, Robert Treat Paine, and Harrison Gray Otis.[4]

The curriculum of the Boston Latin School, the first public school in the American colonies, consisted of Greek and Latin, both written and spoken. Founded by the town of Boston in 1635 under the influence of the Rev. John Cotton, the school, still in existence today, takes pride that it “has taught its scholars dissent with responsibility and has persistently encouraged such dissent.” From its beginning, the town allotted funds to the school for the teacher’s payment.[5]

James must have wondered about the signs of unrest due to British policies that he saw while growing up in the town of Boston. The Knowles impressment riot probably drew his attention when he was ten, as the forced seizure of sailors taken on board His Majesty’s ships, a practice called “the press,” inflamed angry crowds for two days.[6] Those protesting were particularly irate, as the ship’s captain had failed to procure the usual permit to employ the press. The colonists were accustomed to seeing protests and popular uprisings when the occasion demanded it, particularly when local governments failed to act.

James completed his undergraduate studies from Harvard in 1756, graduating with Joseph Trumbull, who would become General Washington’s commissary general when thousands of militias gathered around Boston prior to the ousting of the British. Finishing graduate school in 1759, the same year as Patriot leader Dr. Joseph Warren, he was chosen as orator in 1760 to speak on the death of a beloved Harvard tutor, Henry Flynt. [7]

He then took a position as Usher, teaching alongside his father. In the large square room on School Street that was the Boston Latin School, James and his father expressed vastly different viewpoints about British rule. Master John Lovell supported the British taxation policies, and James the Patriot protests. In this they were not greatly different from many families in Boston. One can imagine the debates and discussion that the two had. My grandmother, Frances Loring Coffin, left for us a journal from 1892 that describes their relationship: “He [James Lovell] was a Whig, and while his father talked loyalty to the King at one end of the Latin school, he inculcated liberty and rebellion at the other.”[8] James married Mary Middleton, of Scottish descent, and they began their family which eventually grew to nine children.[9]

James attended at least some of the meetings of the Sons of Liberty, an informal organization dedicated to instigating protests of what they saw as the unfair policies of the British. Town leaders such as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, John Adams, and James Otis condoned activities that were often public and violent. However, his duties as teacher likely kept him from being a major player. His presence is recorded in a remarkable document that lists 300 members of the Sons of Liberty who gathered for a celebratory meal at the Liberty Tree Tavern in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1769, to commemorate the anniversary of the repeal of the hated Stamp Act. To the sounds of music accompanied by the firing of cannons, those gathered offered forty-five toasts to liberty.[10]

His friends included Josiah Quincy, Jr., a defense attorney at the trial of the soldiers following the Boston Massacre. Quincy was so concerned about the cause of freedom that he travelled to London to speak with politicians he thought might be sympathetic, to urge consideration of the colonies’ needs. Writing to Quincy on November 25, 1774, James expressed his hopes for improvement of the British attitude towards America: “I imagine I may by this Time congratulate you upon a general Change in the Prejudices of the People of England with Regard to us Americans and our Claims. Be that as it may, I can certainly call on you to rejoice at the firm Continuance of that heaven-inspired Union of the Colonies, which you saw form’d before you left us.”[11] Sadly, Josiah Quincy was stricken by tuberculosis and died while on the voyage home.

Riots in 1765, including the ransacking of the home of Lt.Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, protested the hated Stamp tax. In one of the many acts of subversion organized by the Sons of Liberty, Andrew Oliver, elected stamp distributor, was forced to resign publicly in a humiliating ceremony held at the Liberty tree. Master John Lovell likely supported the tax, intended to provide funds for the British army and pay the debt for the French and Indian war, but James stood up for the protestors. Boston celebrated the repeal of the Stamp Act with fireworks, speeches, and the marvelous obelisk created by Paul Revere for the occasion, but the celebration was short-lived as the British imposed new taxes with the Townshend Acts.[12]

On the first anniversary of the tragedy known as the Boston Massacre, James was chosen by the town to deliver an oration at what became an annual tradition to commemorate the event. Over his father’s protests, James Lovell joined hundreds of townspeople at Faneuil Hall, a gathering so large that it had to be moved to the Old South Meeting House.[13] In his speech, he spoke to the problem of taxes not agreed to by the people. “England has a right to exercise every power over us but that of taking money out of our pockets without our consent,” he reminded his listeners. He was careful to make clear his objections, saying, “We are rebels against Parliament—we adore the king.”[14]

When the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, Master John Lovell intoned the words “Deponite libros” that signaled the end of every school day: “Put down your books.”[15] This time his purpose was to close the school. On June 17, James and his family watched from their rooftop as the British sailed across Boston harbor and attacked the thousands of militia dug in on Breed’s and Bunker’s hills. Fire set by hot shot from the British vessels Lively and Falcon consumed the wooden buildings of Charlestown.[16] Though the British prevailed in the onslaught, it proved a Pyrrhic victory, revealing the rebels’ will and ability to fight.

It is not known just what spying activities James undertook to support the Patriot militia, but following the battle, the British discovered evidence linking him to undercover efforts to assist the Patriots. Dr. Joseph Warren, designated major general by the Provincial Congress in June 1775, was killed at Bunker Hill by a musket ball to the head, fighting as a private alongside farmers, working men and other militias. In the pockets of the doctor’s coat, the British discovered letters from James Lovell with information regarding the enemy’s presence in Boston.[17]

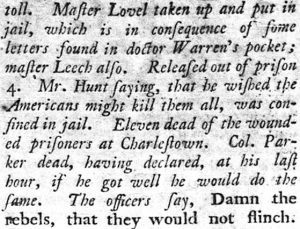

James Lovell, arrested nearly two weeks after Bunker Hill on June 29, must have found a way to help Patriot leaders, possibly by observing British troop strength, overhearing plans, or finding an ally among those who served the British. He may even have found a confidant willing to share plans with him. In any case, the Patriots were ready when the British attack came, and it is likely that he helped them to prepare. The Virginia Gazette of August 11, 1775, published information about James Lovell’s arrest and confinement in jail and refers to letters found in Dr. Joseph Warren’s pocket: “Master Lovell taken up and put in jail, which is in consequence of some letters found in doctor Warren’s pocket; master Leach also. Released out of prison 4 [sic]. Master Hunt saying, that he wished the Americans might kill them all, was confined in jail. Eleven dead of the wounded prisoners at Charlestown. Col. Parker dead, having declared, at his last hour, if he got well he would do the same. The officers say, Damn the rebels, that they would not flinch.”[18]

Josiah Quincy, Sr., writing to John Adams on July 11, 1775, also referred to the letters found in Dr. Warren’s pockets implicating James Lovell in spying: “Poor young Master Lovel, (if not already) will probably soon fall a Victim, to their insatiable Thirst for Blood; on Account of the Contents of some Letters from him, which were found in Dr. Warren’s Packets and which, they say, contain Matters of a treasonable Nature.”[19] And James Warren, who became President of the Provincial Council following the death of Dr. Joseph Warren, also wrote to John Adams, on July 7, expressing his concern for those taken prisoner following Bunker Hill: “The Condition of the poor People of Boston is truely miserable. We are told that Jas. Lovel, Master Leach, and others are in Goal for some trifeling offences the last for drinking Success to the American Army. Their offenses may be Capital.”[20]

In his crowded cell at the Boston Stone Jail were also the navigator John Leach, Peter Edes, the son of Benjamin Edes, who was publisher of the Boston Gazette, William Starr, John Hunt, and others. Journals left by both Leach and Edes provide details of that horrific time, when, confined in close quarters, on a diet of moldy bread and stale water for their first thirty-seven days, they endured the threats and abuse of the British jailers, their only resting places wretched straw pallets on the cold floor. The journals relate the terrible bouts of stomach distress that James suffered. In October of 1775, after pleas from the Massachusetts Provincial Committee and Samuel Adams, Leach, Edes, and others were released, but not James Lovell.[21]

Through the long, cold winter he survived in the stone jail, his rations of food scanty and poor. Probably worst of all to him, with his fine sense of justice and understanding of personal rights, was that he was never formally charged with a crime. His only relief was occasional visits from his wife Mary, who brought him food. In the winter she sent him news of the birth of their eighth child. Mary moved her family into the home of Dr. Joseph Gardner, fortunate for her family since British officers took over their house; she may have performed household duties such as cooking for Dr. Gardner in exchange.[22]

James wrote to Gen. William Howe, General Washington, and anyone whom he thought could help with his release. General Howe informed him through his aid-de-camp Captain Nisbet Balfour that he should request to be exchanged for Col. Philip Skene. On November 19, 1775, he wrote to General Washington to make this request, appealing to the general’s sympathy.

Personally a Stranger to you, my Sufferings have yet affected your benevolent Mind; and your Exertions in my Favor have made so deep an Impression upon my grateful Heart as will remain till the Period of my latest Breath.

Your Excellency is already informed that the Powers of the military Government established in this Town have been wantonly & cruelly exercised against me, from the 29th of June last. I have, in vain, repeatedly sollicited to be brought to some Kind of Tryal for my pretended Crime. In Answer to a Petition of that Sort presented on the 16th of October, I am directed, by Capt. Balfour, Aid de Camp to Genl Howe, to seek the Release of Colll Skene and his Son, as the sole Means of my own Enlargement.

In the letter, James admitted that making such an appeal grated against his sense of self-reliance; still, when he considered the needs of his family, he had no choice.

But while my own Spirit prompts me to reject it directly with the keenest Disdain, the Importunity of my distressed Wife and the Advice of some whom I esteem have checked me down to a Consent to give your Excellency this Information . . . my Family, which must, I think, perish thro’ Want of Fewel & Provision in the approaching Winter, if it continues to be deprived of my Assistance.[23]

Then on December 6 he wrote again, urging General Washington to facilitate his exchange with Colonel Skene.[24]

On December 18, General Washington wrote to Congress, enclosing James’s letter to him and expressing his pity towards the imprisoned citizen.[25] In response to Washington’s letter, on January 5, 1776, the Second Continental Congress resolved, “That Mr. James Lovell, an inhabitant of Boston, now held a close prisoner there, by order of General Howe, has discovered, under the severest trials, the warmest attachment to public liberty, and an inflexible fidelity to his country; that by his late letter to General Washington, he has given the strongest evidence of disinterested publick affection, in refusing to listen to terms offered for his relief, till he could be informed by his countrymen that they were compatible with their safety and honor.”[26]

Further, on the same day, Congress passed a second, related resolution: “That General Washington be desired to embrace the first opportunity which may offer, of giving some office to Mr. Lovell equal to his abilities, and which the public service may require.”[27] The diary of Richard Smith, a delegate from New Jersey, reveals that Congress also on that day took up a collection with the idea of presenting Lovell with one or two hundred dollars. However, they dropped the idea of providing the funds to him as “a bad precedent.”[28]

General Howe did approve an exchange for James Lovell with Colonel Skene, the former governor of Skenesborough on Lake Champlain near Fort Ticonderoga. Skene had been arrested in Philadelphia on his return from London, bringing a Royal Commission that named him as Governor of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, and orders to raise ten thousand men to subdue the rebels, assisted by the crown’s pledge of support of unlimited funds. A prisoner, Colonel Skene was transported to Hartford, Connecticut, where he was confined.[29]In what must have been a cruel disappointment, when James tried to send out a concealed letter with his wife, the smuggled letter was intercepted; General Howe, informed of the action, in February wrote General Washington a terse note, the draft of which went to James, explaining that due to the “prohibited correspondence,” the exchange which he had intended to give him could not take place.[30]

James wrote to his sons Jemmy and Johnny, twelve and thirteen years old, staying in Cambridge with his friend Joseph Trumbull, so that they could help with the harvest and at the same time be two fewer mouths for his wife Mary to feed. His letter reveals his tenderness and concern for them.

I charge you to reflect continually upon that one easy rule for your behavior, which I have repeatedly laid down for you—act in all cases as if I was present. You know I allow you all the diversions suitable for children, but your diversions too often grow into a rudeness which may be corrected by the imagination that I am looking upon you. And if I do, how much more ought you to be kept in order by the thought of the real presence of the great God, to whom you owe an obedience and respect infinitely superior to what is due from you to me, as his love, his care, and his tenderness towards you is infinitely greater than mine.

He concluded the letter in these words:

To conclude, my dear Jemmy, be cautious of what language you make use. My dear Johnny, command your temper—and both my dear boys, be assured of the tokens of the continued love of your affectionate father.[31]

In March, nine months after his arrest, he and others in the Boston Stone Jail awakened to the crash of cannonballs. Writing to General Washington, Col. Henry Knox described his delivery of over fifty cannon, mortars and howitzers from Ticonderoga to Boston as a “Noble train of Artillery.”[32] General Washington directed the Patriots to set them up on Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston and its harbor. The bombardment continued for days.[33] Eventually, realizing he was unable to attack fortifications placed at such a height, General Howe determined to abandon Boston. He assembled a fleet of over a hundred ships, including hired privateers and ships of the British navy, and loaded on board the 8,000 British troops and 1,200 Loyalists, many of them prominent figures within Boston. Among them were Master John Lovell, his wife Abigail, and three daughters. The prisoners in the Boston Stone Jail were marched to the waiting ships.[34]

In the Loring Family Journal is the account that Master John and his family were given upper berths on the same ship that held James and his fellow prisoners, carried deep in the hold. In quaint language, the journal reads, “While his father went to Halifax as an honored guest of England, James was taken as a malignant rebel and spy and kept in close confinement.”[35] Other than the language of the journal, there has been no proof found that both James and his father travelled on the same ship.

Though no one on board knew what their destination was to be before the massive fleet set out, and indeed James and his fellow prisoners must have thought it likely they would end up in New York, occupied by the British, their destination was to be the rough frontier settlement of Halifax, Nova Scotia. There, near a deep harbor, the British fort the Citadel provided a defense for the king’s troops. James and the other prisoners were placed in the Hollis Street Prison for the next months, a rough, boarded up former house.[36] In these cramped confines, he and perhaps thirty other prisoners endured a poor diet of scraps left over from British officers’ tables, while sickness raged among the men. James continued to write letters, to General Washington, to the diplomat Arthur Lee, to anyone whom he thought might have some influence, hoping for an exchange.

In August 1776, a colorful figure joined those prisoners in the jail. Ethan Allen, leader of the Green Mountain Boys, had been arrested following an attempt to take Montreal in the fall of 1775, sent to England and transported back to North America. Before his imprisonment, in May 1775, at the request of the Connecticut militia, Allen led the Green Mountain Boys along with militia from Connecticut and Massachusetts to take Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. Just as they were about to embark on their raid, Col. Benedict Arnold arrived, sent from the Massachusetts Committee of Safety. Arnold insisted on joining Allen to command the expedition, as Ethan Allen made it clear he would not hand over his command. Their party succeeded in taking Ticonderoga and the fort at Crown Point from the British with little mishap. Joining Gen. Richard Montgomery’s invasion of Montreal in the fall, Ethan Allen was captured.[37]

Ethan Allen’s Narrative explains that he befriended James Lovell in the prison in Halifax. When James was freed, Allen said, “after this I had the happiness to part with my friend Lovel . . . whom the enemy affected to treat as a private; he was a gentleman of merit, and liberally educated, but had no commission; they maligned him on account of his unshaken attachment to the cause of his country.”[38] James Lovell no doubt was amazed to learn that Ethan Allen had tried to obtain independence for the New Hampshire Grants by suggesting they become a new Royal Colony, under the governorship of Colonel Skene, the same British officer that General Howe had suggested for his exchange.

Finally James’s exchange did come through, due to the mediation of General Washington. Amazingly, he would be swapped for Colonel Skene. James and the political prisoners, including Ethan Allen, were taken to New York in October of 1776.[39] Freed, James reached his home in Boston on November 30, eighteen months after his arrest, emaciated and weak. Soon after, he received a letter from the Second Continental Congress, requesting his attendance. He thought over his response for a week, considering his weakened state and already long absence from home, but the privilege of serving his country along with the necessity of earning a living to help support his family won out, and he responded to the Deputy Secretary of the Council of Massachusetts, on December 24, 1776, agreeing to join Congress.[40]

James Lovell left Boston and met John Adams at his home in Braintree; the two set out on January 9, 1777, to Congress’s meeting place in Baltimore.[41] As a representative from Massachusetts, he was a well-known figure; a teacher at a prominent Boston school; an articulate speaker. And he had proven his loyalty in surviving prison at the hands of the British. He was as dedicated and committed a Patriot as one might find. During his time in Congress, he utilized those talents and developed others, such as his expertise in cryptography, which enabled him to assist in deciphering intercepted British messages. Holding to the values which guided him during stormy times in Boston and harsh months in prison, he prevailed to do his part to guide the country despite lack of funding, internal dissension and personal hardship.

[1]Helen Francis Jones, James Lovell in the Continental Congress, 1777-1782 (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1968), 33.

[2]Samuel Osgood to Samuel Holten, April 16, 1782, in Edmund Cody Burnett, ed,Letters of Members of the Continental Congress (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution,1921), 6: 328n2, archive.org/details/lettersofmembers06burn/page/328/mode/1up.

[3]James Lovell to Joseph Trumbull, November 28, 1777, in Paul H. Smith, et al., eds. Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), vol. 8: September 19, 1777 to January 31, 1778, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:6:./temp/~ammem_W3os::

[4]Henry F. Jenks, Catalogue of the Boston Public Latin School, Established in 1635 (Boston: The Boston Latin School Association, 1886), 330-388, archive.org/details/catalogueofbosto00bostrich.

[5]“Boston Latin School History,”Boston Public Schools, www.bls.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=206116&type=d.

[6]Thomas Hutchinson, History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, vol. 2 (London: J. Smith, 1768), 430-435, books.google.com/books?id=tsQUAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false; referenced in Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776 (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1991, 1972), 6-7.

[7]James Lovell, “A Funeral Oration for Tutor Flynt” (Boston, 1760), 1, Harvard University Archives; Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, vol.14, Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College, 1756–1760, “James Lovell, 1756” (Boston, Massachusettts: 1968), Massachusetts Historical Society, HathiTrust Digital Library, 32-47; also see “Joseph Warren, 1756,” 510-527; and “Joseph Trumbull, 1756,” 96-106, catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101759318.

[8]James Lovell Loring and Emma Gephart Loring, Loring Family Journal,1892, hand copied circa 1978 by Frances Loring Coffin (collection of Jean C. O’Connor), 22-23.

[9]Shipton, “James Lovell, 1756,”32.

[10]“An Alphabetical List of the Sons of Liberty Who Din’d at Liberty Tree, Dorchester,” Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/8

[11]William Vail Kellen, “June Meeting. Gifts to the Society; American Embassy at Berlin, 1917; Rev. John E. Stewart in Kansas; American Service of the Azans; Quincy’s London Journal, 1774-1775; Letters to Josiah Quincy, Jr.; Conversion of John Thayer, 1783; Samuel Savage Shaw,” James Lovell to Josiah Quincy, November 25, 1774, “Letters to Josiah Quincy,” 477, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 (1916): 413-503, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25080064.

[12]“Joy to America! Colonists Respond to the Repeal of the Stamp Act, 1766,” Making the Revolution: America, 1763–1791. America in Class, from theNational Humanities Center, 3-4, americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/crisis/text3/stampactrepealresponse1766.pdf.

[13]Shipton, “James Lovell, 1756,”33-34.

[14]James Lovell, “An Oration Delivered April 2, 1771” (Boston: Edes & Gill, 1771), Early American Imprints, Harvard Archives, from NewsBank, Inc. and the American Antiquarian Society.

[15]Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, vol.8,Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College, 1756–1760,“John Lovell, 1728” (Boston, Massachusetts: 1951), Massachusetts Historical Society, 445, catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101759318.

[16]Shipton, “James Lovell, 1756,” 36.

[17]James Warren to John Adams, July 7, 1775, fn. 5,Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0041.

[18]“Master Lovell taken up and put in jail,” Virginia Gazette, August 11, 1775, extract of a letter from Cambridge, July 12, The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture).

[19]Josiah Quincy to John Adams, July 11, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives,founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0045.

[20]James Warren to John Adams, July 7, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0041.

[21]Peter Edes,pioneer printer in Maine: a biography: his diary while a prisoner by the British at Boston in 1775, with the journal of John Leach, who was a prisoner at the same time, ed. Samuel Lane Boardman (Bangor: The De Burians, 1901), 93-109,

books.google.com/books/about/Peter_Edes_Pioneer_Printer_in_Maine_a_Bi.html?id=lvU-AAAAYAAJ; John Leach, “A Journal Kept by John Leach, During his Confinement by the British, in Boston Gaol, in 1775,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, vol. 19 (Boston, Massachusetts, 1865) 255–263.

[22]James Spear Loring, The Hundred Boston Orators, from 1770 to 1852 (Boston: John P. Jewett and Co., 1852), 34-35, archive.org/details/hundredbostonora00lorin.

[23]James Lovell to George Washington, November 19, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0368.

[24]James Lovell to George Washington, December 6, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0453.

[25]George Washington to John Hancock, December 18, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0528.

[26]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Worthington C. Ford eds. et al. (Washington, DC, 1904-37), 4: 33, memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=lljc&fileName=004/lljc004.db&recNum=32&itemLink=r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00410))%230040033&linkText=1

[28]Richard Smith, Diary, January 5, 1776, in Letters of Members of Continental Congress, 1: 297, archive.org/details/lettersofmembers01burnuoft/page/297/mode/1up?q=Skene.

[29]Eliphalet Dyer to Joseph Trumbull, June 8, 1775, Letters of Members of Continental Congress, 1: 115, archive.org/details/lettersofmembers01burnuoft/page/115/mode/1up?q=Dyer.

[30]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: William Howe to George Washington, February 2. February 2, 1776, Manuscript/Mixed Material, www.loc.gov/item/mgw444447/.

[31]Letter from James Lovell to his sons, written in the Boston Stone Jail, September 21, 1775, original in the collection of the author.

[32]Henry Knox to George Washington, December 17, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0521-0001.

[33]Richard Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1903), ]295-301.

[34]Shipton, “James Lovell, 1756,”39.

[35]Loring and Loring, Loring Family Journal, 23.

[36]John Blatchford, The Narrative of John Blatchford, Detailing His Sufferings in the Revolutionary War, while a Prisoner with the British,introduction and notes, Charles L. Bushnell (New York: privately printed, 1865), Notes, 73, archive.org/details/narrativeofjohnb00blat/page/73/mode/2up.

[37]Ethan Allen, A Narrative of Col. Ethan Allen’s Captivity (Burlington: Chauncey Goodrich, 1846), 9-33.

[40]Peter Force, American Archives: Fifth Series: Containing a Documentary History of the United States of America from the Declaration of Independence July 4, 1776, to the Definitive Treaty of Peace with Great Britain, September 3, 1783, vol. 3 (Washington DC: January 1853), 1412.

[41]John Adams to Abigail Adams, January 9, 1777 (Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 2, June 1776 –March 1778), Adams Papers Digital Edition, Massachusetts Historical Society,

www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/ADMS-04-02-02-0100#sn=4.

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...