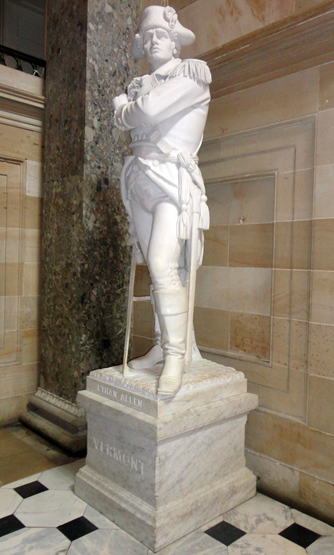

Photo courtesy of author.

The Controversy

In the region we call Vermont today land claims were vociferously contested between settlers from New York and from New Hampshire during the American Revolution. Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys who aggressively protected their perceived property rights were ringleaders of the New Hampshire claimants. The New Yorkers were equally forceful in pursuing their property rights, offering cash rewards for the capture of Ethan Allan and other Green Mountain Boys leaders.[1]

Initially, Allen demonstrated support for the rebel cause with his daring capture of Fort Ticonderoga. But as the war dragged on with an uncertain ending and the Continental Congress refusing to recognize the Vermonters’ land claims, Allen and other political leaders of their self-proclaimed Republic of Vermont were open to negotiating a separate peace with the British Empire.

Sensing an opportunity, Frederick Haldimand, Royal Governor of Canada, offered protection and status as a separate British Colony to Vermont in exchange for terminating Vermont’s support of the 13 rebellious colonies. Through intermediaries, Haldimand opened negotiations with Allen and other influential Vermont politicians and leaders.[2]

Ethan Allen asserted that he had no intention of becoming a “damned Benedict Arnold”[3] but also said “I shall do everything in my Power to render this State a British province.”[4] Was Allen, the fabled conqueror of the British fortress at Ticonderoga and a children’s storybook hero, really a turncoat on the order of Benedict Arnold, Allen’s co-commander in capturing Ticonderoga? What follows is a presentation of the facts as best as they can be known today and an informed conjecture of Allen’s true intentions.

Background

In 1749, New Hampshire Royal Governor Benning Wentworth began selling land grants west of the historical boundary of the Mason Line, which follows the Merrimack River. At the same time the New York governor, believing that he had jurisdiction over land north of the Massachusetts border extending east to the Connecticut River, sold land grants to aspiring New York settlers. Soon there we two “rightful” land owners vying for the same property and major disputes ensued.[5]

In 1764, King George III decided the dispute in favor of New York but delayed implementation. However, Governor Wentworth continued to sell land grants. As the inevitable conflicts arose, a group called the Green Mountain Boys, a paramilitary force led by Ethan Allen, banded together to forcibly protect their New Hampshire land grants and ward off the New York authorities. Allen was aggressively protecting the 60,829 acres that he jointly owned with other family members in northern Vermont between the Green Mountains and Lake Champlain.[6]

There were mainly non-lethal skirmishes between the Green Mountain Boys and the New York authorities but considerable property was destroyed. New York could not enforce its laws and land ownership disputes continued throughout the American Revolution.

Vermonters in a Squeeze

In 1780, the British planned a complex three-phase plan to end the stalemated American rebellion. Previous fighting around New York City had devolved into a deadlock with the British safely ensconced in New York City and the Continental Army holding a ring of positions around the city.

The first phase of the British plan was to send an army under Lord Cornwallis to invade the southern states and rally the considerable number of loyalist residents. In a second action, the British tried to turn Continental Army officers including Israel Putnam, Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen, with grants of money, land and title.[7]

The third phase was to negotiate a separate peace with the nascent state of Vermont and bring the northern frontier back into the British Empire. Lord George Germain, British Secretary of State for America in Lord North’s cabinet, recognized the unresolved dispute and sought to exploit the Vermonters’ plight by recognizing their land claims.

The Vermonters were facing a desperate situation. Since the Battle of Valcour Island on October 11, 1776, the British exercised undisputed control of the waters of Lake Champlain and could launch unopposed invasions into Vermont. There were approximately 10,000 Redcoats in Canada and virtually no Continental Army or New York Militia units in Vermont to oppose them. Even the Continental regiment formed by Vermonters and led by Colonel Seth Warner was stationed in New York to defend New York soil.[8] The Vermonters were left on their own to face an overwhelming enemy.

As a way out of this tight squeeze, several Vermont leaders including Ethan Allen opened negotiations with the British to return as a separate province in the British Empire. Intense intrigue continued until the Treaty of Paris was signed in September 1783.

There are three potential explanations for the actions of Ethan Allen and his fellow Vermonters:

- Ethan Allen was a fervent and heroic patriot. He was aware of the British objectives to turn high profile rebel leaders and played along to forestall British invasion and obtain the return of over 200 Vermonters from Canadian captivity.

- Ethan Allen was principally a promoter protecting his land holdings. Allen and his coterie employed an old Native American tactic of playing two more formable foes against each other to stave off destruction.[9] Allen and the Vermonters showcased negotiations with the British to force the Continental Congress to recognize Vermont. However, if the Americans lost the revolution, Vermont would be in a position to be a separate colony from New York and New Hampshire.

- Ethan Allen was a traitor to the American cause. In 1780, the military situation looked bleak for the Americans and Allen may have lost faith in the Continental Congress’s desire to formally recognize Vermont as a separate state. Therefore he was actively preparing Vermonters to re-join the British Empire and only the momentous defeat of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown invalidated his plans.

The case for each of these explanations is presented below along with a concluding assessment.

Ethan Allen as a Patriot

A strong case can be made that at the outbreak of the revolution Ethan Allen quickly sided with the rebel cause. After Lexington and Concord, Allen initiated aggressive offensive operations against the British Empire by capturing Fort Ticonderoga, the first British post surrendered to the rebellious Americans. No matter how lightly defended the fort was, this was a courageous act against the world’s most powerful empire. Further, he proved his patriotism in the Canadian invasion when, although not selected as an officer to lead the Green Mountain Boys, he nevertheless accompanied the army in a civilian capacity. He was captured and sent to England under heavy restraints and in miserable conditions. This harsh treatment at the hands of the British may have permanently secured Allen to the American cause.

As the leader of the Green Mountain Boys and a harshly treated prisoner, Allen felt a special loyalty to captive Vermonters incarcerated by the British in Canada. At the time of the Haldimand negotiations, there were over 200 Vermonters held in the Montreal Provost and on Prison Island 45 miles upstream on the St. Lawrence.[10] George Washington ordered that no civilians be exchanged and that the Continental Army control the exchange of officers and enlisted men. So if Allen had a hope to obtain the return of his neighbors, he would have to negotiate separately and directly with the British. As Congress did not recognize the Republic of Vermont, he felt free to enter negotiations for a “cartel for the exchange of prisoners” with Haldimand.[11]

Ethan Allen as a Land Promoter Protecting his Property

Initially Allen may have been motivated to attack Fort Ticonderoga as King George III was deferring recognition of the Vermonters’ land claims. If the British were not going to recognize their claims, the Vermonters would ally themselves with the rebellious colonists to attempt to get recognition from the Continental Congress for their land claims.

Further demonstrating Allen’s interest in protecting his property, the only time he left Vermont to fight the British was in support of the invasion of Canada and this was done to advance his personal economic interests. Water transport was critical and Lake Champlain flowed into the St. Lawrence River providing trading access for Vermont products. This made control of Montreal and Quebec considerably more important in 1775 than it is today. Although he earned a Continental Army commission he never again ventured out of Vermont, staying within to protect his land interests through his political dealings and militia leadership.

Like most Americans in 1780, Allen was tiring of war and willing to do what it took to protect his property and livelihood. Allen certainly was not fighting for either New York or New Hampshire and had little support for the Continental Congress, which would not recognize Vermont. So Allen’s economic interests were possibly paramount and he sought to create a separate Republic of Vermont to enforce land rights.

Ethan Allen as a Turncoat

Dithering by the Continental Congress may have caused Allen to lose faith in its formal recognition of Vermont as a state. Therefore his only course of action may have been to ally with the British who through Haldimand offered to legitimize the Vermonter land claims.

During 1780 and 1781 several sets of intense negotiations were conducted with the British over the status of Vermont.[12] In November 1780, the Vermont General Assembly tried Ethan Allen for his correspondence with the British. He was exonerated but in a fit of pique resigned his generalship in the Vermont militia.[13] However he continued to work with Vermont political leaders to pursue peace with the British.

In May 1781, the Vermonters agreed to a cartel for the exchange of prisoners that also included a truce for all territory between Vermont and the Hudson River.[14] Subsequent to this truce, Vermont and the British negotiators continued to discuss terms by which Vermont would rejoin the British Empire. However, consensus among the Vermonters could not be reached. At the war’s conclusion, the ostensibly traitorous agreements were not concluded and the exchange of prisoners was the sole result of the three-year Haldimand negotiations.

Success

In the end, Ethan Allen and the Vermonters obtained their desired outcome: Vermont was saved from British invasion, its captured citizens returned before other Americans in British captivity, and it prospered as an independent republic until 1791. Contemporary historians with access to personal testimony of principals emphasize Allen’s patriotism and service to the citizens of Vermont:

“Thus while the British Generals were fondly imagining that they were deceiving, corrupting and seducing the people of Vermont by their superior arts, address and intrigues, the wiser policy of eight honest farmers, in the most uncultivated part of America, disarmed their northern troops, kept them quiet and inoffensive during three campaigns, assisted in subduing Cornwallis, protected the northern frontiers, and finally save a State.”[15]

Later historians emphasized the focus on protecting Vermonters’ land claims:

“Only a situation of extraordinary danger would justify the policy adopted by the Vermont leaders in the Haldimand negotiations. Surrounded on every side by avowed enemies or covetous neighbors, weakened by internal dissentions, with Congress indifferent if not hostile, deserted by those who should have been her friends, threatened by invasion from a force great that she could muster, Vermont’s existence as a State was threatened and the lives and property of her citizens were imperiled. A desperate situation like this could not be met by the use of ordinary methods. The Vermont leaders were playing with fire but they handled the perilous situation with such consummate skill that they preserved a brave little commonwealth from destruction and their own reputations from obloquy.”[16]

The British believed that Allen and the Vermonters were traitors. Sir Henry Clinton in his war memoirs supports this perspective:

“At any rate I have little doubt that, had Lord Cornwallis only remained where he was ordered, or even after his coming into Virginia had our operations there been covered by a superior fleet as I was promised, Vermont would have probably joined us.…”[17]

Haldimand was more suspicious of Allen and the Vermonters’ motives:

“I am assured by all that no dependence can be had in him – his character is well-known, and his Followers, or dependents, are a collection of the most abandoned wretches that ever lived, to be bound by no Laws or Ties.”[18]

Allen’s participation in the American Revolution underwent three distinct phases, during which his loyalty was contingent upon the existing geopolitical situation between the tories and the patriots. The historical Ethan Allen was a combination of all three caricatures: a patriot for attacking the British at the Revolution’s outset; a land promoter maximizing the value of his holdings during the conflict; and, during the last years of the war, a turncoat for hedging his bets as America’s prospects looked bleak up to the victory at Yorktown and the successful negotiation of the Treaty of Paris.

[1] A £20 reward was offered by New York officials on each of the leaders of the Green Mountain Boys and in return Ethan Allen offered a £25 reward on each New York official. William Sterne Randall, Ethan Allen – His Life and Times (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2011), 260-262.

[3] Captain Justus Sherwood, “Journal – Miller’s Bay October 1780,” Vermont History (April 1956), 102.

[4] Ethan Allen to Frederick Haldimand, June 16, 1782. Ethan Allen and His Kin: Correspondence, 1772-1819, ed. John J. Duffy, Ralph H. Orth, J. Kevin Graffagnino, Michael A. Bellesiles (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1998), 130-131.

[5] For a listing of the New Hampshire Grants see Appendix I and for New York Patents see Appendix II, in Esther M. Swift, Vermont Place-Names – Footprints of History (Brattleboro, Vermont: The Stephen Greene Press, 1977), 571-599.

[6] The acreage owned was as of July 1775. For a chart of acreage by town see James Benjamin Wilbur, Ira Allen – Founder of Vermont (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928), Volume II 522-525.

[7] Michael A. Bellesiles, Revolutionary Outlaws – Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 195.

[8] Frederic F. VandeWater, The Reluctant Republic – Vermont 1724-1791 (New York: The John Day Company, 1941), 257.

[9] For a more complete description of Native American tactics borrowed by Ethan Allen see Michael A. Bellesiles, Revolutionary Outlaws – Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier, 187.

[10] Neil Goodwin, We Go as Captives – The Royalton Raid and the Shadow War on the Revolutionary Frontier (Barre and Montpelier: Vermont Historical Society, 2010), Preface XVII.

[11] Ira Allen, History of the State of Vermont (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1798), 100.

[12] For a description of the Haldimand negotiations see A. J. H. Richardson, “Chief Justice William Smith and the Haldimand Negotiations”, Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society Volume IX No. 2 (June 1941), 84-114.

[13] Ethan Allen and His Kin: Correspondence, 1772-1819, ed. John J. Duffy, Ralph H. Orth, J. Kevin Graffagnino, Michael A. Bellesiles, 112.

[15] Samuel Williams L.L.D., The Natural and Civil History of Vermont – Volume II (Burlington, VT: Samuel Mills, 1809), 216.

[16] Walter Hill Crockett, Vermont – The Green Mountain State – Volume II (New York: The Century History Company, Inc., 1921), 343.

44 Comments

Great article. It shows that Ethan Allen was a strong leader who was also a pragmatist. We often forget how uncertain life could be for those who lived in the wilderness during the revolutionary war and colonial period.

Let’s remember in those days Americans were divided about whether to have a revolution or not. A third wanted independence another third wanted to stay with England and the rest just wanted to tend to their daily lives. Allen did what any leader, politician, businessman would do. He played one party against the other and did what it took to look after his interests, family interests and the community they came from. At the end it was a job well done. Vermont became part of the most powerful country, a stand out state with half of the population of what NH with a great reputation. It was a republic then a state and it has it’s own kingdom 🙂

Well said!

It was a territorial imperative to protect the claims he steaked.

A superb article and one that made me think a great deal. Often I find my American friends assume the revolution was somehow a fait accompli. So this is concise and thought-provoking is a neat reminder that events and actions were not simply a matter of being black and white. Certainly one has to admit that Ethan Allen’s motivations were greatly varied and nuanced. Personally, I think he rather adeptly played the Great Game and, in the end, came up trumps.

PS not sure about the following line: “The British believed that Allen and the Vermonters were traitors”. Is “traitors” really the right word?

Thank you for your comments and I agree that I should have clarified “traitors to the American cause” to be consistent with the British perspective.

Looking at the record of the Vermont leaders during the last years of the war, it is difficult not to see them as either traitors or opportunists. At the time Ethan Allen, his brother Ira and other leaders in VT were negotiating with the British, the American prospects for winning were exceedingly dim. Washington was very unhappy that the Vermonters were even talkiing to the British. I think an unaddressed problem resulting from the talks was the affect that it had on Washington’s outlook when he thought that Vermont would sell him out. If the talks were a game, Washington was not in the loop. Regardless of the motive and intent of the Vermonters, the impact on morale of the officers at headquarters with Washington must have been devastating.

I have a hard time seeing how Ethan and the others are heroes when they were acting out of at best total self interest. I congratulate Gene Procknow for raising this issue which has too long been left in the dark.

Perhaps we would have liked to see a bit more attachment to the cause in Allen and the other Vermont leaders but I don’t see where the new nation was making very many promises to them either. Hard to choose against a man’s own property rights in favor of a country that doesn’t yet exist and leaders who promise him little.

One of the things I wonder about is Ethan’s attachment to the cause early in the war. To my knowledge, we don’t really have a record indicating exactly why Allen was heading for Ticonderoga. Do we?

We do know that Ft Ticonderoga is clearly located in NY, whose governor placed a price on Allen’s head. The best rationale is that Allen was attacking the rule of King George III as he would not formally recognize the New Hampsire claimants. However as you point out this would not obviate the New Yorker claimants which persisted until 1791. Most likely Allen’s capture of the famed, though lightly defended fortress was designed to intimidate the New York authorities and legitimize the New Hampshire claimants as a political force.

We know that Ethan and his Green Mountain Boys were the largest component of a force that was initiated in Hartford, CT after the Lexington Alarm, picked up addition men in the Berkshires and then met Ethan in Vermont and he joined their campaign as its leader. There is no documentation of why Ethan and his boys agreed to join. However, it is difficult to see how their support of the New Hampshire claims was advanced by this activity. By June, CT had been given responsibility for the defense of Fort Ti and both Etahn and Benedict Arnold were dismissed. THe New York Governor who put a price on Ethan was a British appointee and the NY Assembly was not willing to step in to defend Ti after its capture. In the end, Ti’s capture did little for the New Hampshire claims.

It is likely that planning the capture of Fort TI was initiated before Lexington and Concord. John Brown sent by Massachusetts to Montreal to ascertain the intentions of the Canadians with respect to their support for the British. He was guided by Peleg Sunderland and Winthrop Hoyt through Vermont to Canada. Brown concluded “The fort at Ticonderoga must be seized as soon as possible, should hostilities be committed by the King’s troops. The people on New Hampshire Grants have engaged to do this business.” Another motivation of the Green Mountain residents may have been to protect their isolated properties from British incursions ala Lexington.

Well written, Gene. Good point on John Brown, he had made those suggestions to another authority, the Boston Committee of Correspondence. With the various Committee’s, it’s easy to see how his recommendations could have fallen on deaf ears. To his everlasting detriment, Arnold unintentionally initiated the whole Connecticut plan and recruitment of Allen.

The unintentional fuse was lit when CT’s Colonel Samuel Parsons was on his was back to Hartford after leaving Cambridge shortly after Lexington / Concord. He happened to cross paths with Arnold, headed to Cambridge from New Haven. Parsons admitted in a letter to Joseph Trumbull that he had mentioned to Arnold that there was a shortage of artillery for the Patriots in Boston and that Arnold talked to him about the conditions and ordinances at Fort Ti. Parsons immediately informed prominent citizens in the Hartford area, including Silas Deane. Without legal authority, this small group of prominent individuals ended up planning and providing the necessary funding for the CT expedition that could take on a contingent the size of Allen’s Green Mountain Boys. Allen’s brother Heman was among those in the initial party from the Hartford / Salisbury group. The point shouldn’t be lost that Brown and Allen were waiting for direction hopefully from a provincial authority. Brown had informed the Committee of Safety a month before Arnold yet nothing developed. Allen wasn’t going anywhere unless he had the necessary funding to carry on such an endeavour with a 200+ small army.

Arnold, of course, made an impression with his Footguards upon arriving in Cambridge. He came into contact with Joseph Warren and provided his intelligence on the weaponry and troop strength at Fort Ti, which was on the money, and further passed it on to the Mass Committee of Safety. (One has to wonder where and when Arnold received such intelligence; likely his merchant contacts) The Committee of Safety was convinced, and provided Arnold the funding to recruit troops and attack the Fort.

If Arnold hadn’t said a word to Parsons, in all likelihood, he would have attacked Fort Ti a few days after May 10, 1775, with his recruits. (At the time being raised in Western Mass) Allen would have never been involved. Granted Allen might have just lied as usual and claimed he took the Fort by himself; maybe further embellishing his “In the name of the great Jehovah, and the Continental Congress” delusional anecdote.

Jeff, a well written description of the role of Samuel Parsons in rallying the Connecticut Patriots to attack Fort TI. By moving quicker than Arnold’s militia mobilization, the combined Connecticut, Massachusetts and Green Mountain Boy contingent was able to completely surprise the fort’s defenders. If more time had elapsed, there would have been more risk of local Tories warning the fort and making its capture difficult or impossible.

Your point on Allen’s fabled surrender demand is also a good one. The first Continental Congress did not recognize the New Hampshire Grants and given Allen’s deist religious views he was unlikely to invoke God’s name To spur any action.

Col. Samuel Parsons continued his service in the patriot cause. He served in the Continental Army in the NYC campaigns of 1776 and in the Hudson Highlands through the end of the fighting. While his roles were primarily defensive and small unit skirmishes, Congress promoted him to Major General in October 1780. His army service continued thought the end of hostilities and he returned to a law practice and subsequently a western land developer.

First off, as Gene knows, I have dim view of Ethan Allen. Even darker of Arnold.

Allen as a Diest:, Allen’s Deist treatise “Reason, the only Oracle of man”, was not published until 1785, almost a decade after Ft Ticonderoga. Allen was not recognized as a diest at the time of the Ft Ticonderoga expedition. Note that Deism is not atheism – Allen’s “Reason” treatise fully acknowledges “God”, uses the term “Jehovah”, but advocates for a natural belief in God rather than submission to what he asserted was a human contrivance of formal religion. Allen’s beliefs, as published a decade later, would not have prohibited a claim that his actions were a result of a belief in a supreme being. To the contrary, his published beliefs would have supported an action taken to liberate Godly humans from the formal Church of England “contrived” religion mandated by the Crown. Moreover, to get to the exact point, Allen’s “Jehovah and the Continental Congress” statement was not attributed to him by some other person; Allen himself claimed that he made that statement in his pamphlet “The Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen”, which he wrote and published in 1779 after he was released from British captivity (”Narrative of” Allen’s chronicle of his capture by the British near Montreal and an indictment of the inhuman conditions imposed of those held prisoner by the British). As a way of establishing his bona-fides and explaining the sentiment towards him in Britain, Allen briefly covers the capture of Ft Ticonderoga and claims to have made the famous statement. No contemporary challenged his claim to have made the “Jehovah and the Continental Congress” statement, as I’m not aware that anyone present at the capture, including Benedict Arnold, challenged Allen’s claim. In either case, whether Ethan Allen actually said it at the time of the Ft Ti assault or “invented” it when writing his “Narrative” pamphlet, the words were Ethan Allen’s.

Arnold as the originator of the Ft Ticonderoga expedition is false. His chance encounter with Parsons on 27 April did nothing more than offer additional opinion on the vulnerability of the fort. In the first case, the status of the fort wasn’t a secret. It was known to be in ruins as British authorities over the years had repeatedly called for and attempted to gain funding for its repair – and American civilians also advocated for the defense of troops at Ft Ti and for its repair and maintenance as a deterrence to native raiding. Arnold himself did not claim first-hand knowledge of the fort’s status, but attributed his awareness to the comments made to him by fellow businessmen. Surely he wasn’t the only one they told! There is substantive evidence that Connecticut was planning the Ticonderoga expedition before Parsons chanced to meet Arnold. Connecticut Colonel Saltonstall, writing at 7:00 AM on 25 April to Silas Deane ((Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society, Volume 2, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, 1870, pg 218-219, available as a free google ebook at https://books.google.com/books?id=tgQoAQAAMAAJ&dq=correspondence+of+silas+deane,+saltonstall&source=gbs_navlinks_s ), states that his observation of American forces besieging Boston conformed to his plan, and describes the need for cannon which should be positioned to effect American capture of Boston – notably specifically naming Dorchester Heights to command Boston and the harbor. Pointedly, this was the plan that was eventually pursued. Saltonstall names sources for those cannon and includes those at Crown Point which he states could be there in about a month. Saltonstall could not have made that statement without the knowledge that a plan to obtain the cannon on Lake Champlain was already formulated and included a concept for moving them to Boston. Saltonstall’s letter implies just that, and further states that Captain Mott could describe the details. On April 27, before Parson’s arrival from Cambridge, the Connecticut Committee of Safety in Hartford transferred Capt Mott from Saltonstall’s command to that of Colonel Parsons. Mott reported to the Committee of Safety at Hartford on 28 April, where he was recruited into the Ft Ti expedition. He found that the plan had already been set in motion the day before, with men already travelling to key contacts to initiate the expedition. And who were those contacts…? The included key people with direct, primary source-provable contact with Ethan Allen: Ethan’s brother Heman — still living in Connecticut running an ironworks that would subsequently produce hundreds of cannon for the Continental Army; Capt John Brown — who Massachusetts CoS commissioned on 15 Feb 1775 to conduct a reconnaissance of the New Hampshire Grants and lower Canada, and who travelled from his home in western Massachusetts through Bennington where he had sufficient contact with the command center of the “Green Mountain Boys” to obtain as his guide for the reconnaissance Peleg Sunderland (one of Ethan Allen’s closest Lieutenants and a man warranted for death on sight by the New York Royal Government); Reverend James Easton, who, like Allen, was a deist disciple of Dr Young and also the elected Colonel of the local militia; and not to mention a stop to obtain assistance from Mrs. Ethan Allen (who was living with their children on a farm in Massachusetts — Mott’s expense accounts show $3 paid to Mrs. Ethan Allen during the trip north). Let’s not forget that Capt Brown wrote his 29 March letter to the Massachusetts CoS imploring secrecy for a plan to capture Ft Ticonderoga, and that his letter included the key information that the New Hampshire Grant people had committed to undertake the capture, and that a secure means of communication had been established to that effect. These key facts are often excluded from quotes of Brown’s letter, but they critically tell us that the people of the New Hampshire Grants (the Green Mountain Boys) were already on the task and that they were in communication with an authority other than Brown’s contacts in Massachusetts. Brown doesn’t say who, but the obvious answer is Connecticut (it certainly wasn’t New York!). I believe its generally understood that Allen’s family, like many of the New Hampshire Grant settlers, were from Connecticut and they had primary ties to that colony (one of the original proposed names for the republic created from the New Hampshire Grants in 1777 was “New Connecticut; Dr Young is credited with “Vermont”). With Brown in Bennington late Feb-early March, its likely no coincidence that Ethan Allen wrote a letter to Connecticut authorities on 1 March 1775 stating that in the event of hostilities he would induce the Green Mountain Boys regiment to serve as rangers. That letter evidences the origination of correspondence between Connecticut and Allen, and lends validity to his later claim, on the eve of the capture of Ft Ticonderoga, to be acting pursuant to “secret instructions” by private letter from the Connecticut government (keeping in mind that the men who signed for the money from the Connecticut treasury, who set the Ft Ti expedition in motion, gave Capt Mott his orders, were members of the Connecticut Committee of Safety, the only government in being in absence of Crown authority). The pieces all fit – Connecticut had a plan long before Arnold happened to meet Parsons.

Rather than attribuiting Arnold with the idea to take Fort Ti, the greater likelihood is that Parsons knew of the Connecticut plan – he was returning from the Boston siege where he had served with Saltonstall and Mott, and was also a member of the Connecticut Committee of Safety chaired by Silas Deane – to whom Saltonstall’s letter was addressed. Suppose that either before or after Arnold passed-on his second-hand information regarding Ft Ti, Parsons shared with Arnold the Saltonstall-outlined plan to have the cannon on Dorchester Heights in about a month, and told Arnold that the job was to be done by the New Hampshire Grant regiment. Arnold then wasted no time in seeking out a role for himself by advocating to Massachusetts his leadership of such an expedition, but without telling Massachusetts that someone else was already on the job. We know he didn’t follow his orders to recruit a regiment, but rather rushed to “the Grants” in order to arrive in time to assert his paper authority and take credit for the work of others. The attitude of literally all of the other men serving leadership roles at the Capture of Fort Ti and Crown Point, the subsequent embarrassed, apologetic letters of the Massachusetts CoS to sister colonies, as well as its recall of Arnold from Ticonderoga and his dismissal from Massachusetts service, support this version. In either event, primary documents indicate that Connecticut had a plan in the works long before Parson’s chanced to meet Arnold on the Hartford-Cambridge road. Arnold’s contact with Parsons had little impact on Connecticut’s formation of the Ticonderoga expedition; just as Arnold’s late arrival with no men, no provisions, and no plan had no effect on its capture other than to muddle history, and leave Arnold with the first of many chips on his shoulder.

Jim, I agree with your distinction about deism and your assertion that CT leaders were already planning the capture of Ft. TI before Arnold’s chance encounter with Parsons. Further as you point out, it is clear that Ethan Allen wrote the words, “In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress” in his captivity narrative. I surmise that Allen wrote the colorful and poetic phrase as a literary embellishment intended to raise his personal stature and to curry favor with the Continental Congress.

Allen French (The Taking of Ticonderoga in 1775: The British Story, page 84) researched this topic comparing a written statement by British Lt. Feltham with Allen’s captivity narrative and several other oral histories. Feltham indicated that when he questioned under whose authority surrender was demanded, Allen and Arnold replied that it was the Provincial Congresses of Massachusetts and Connecticut. French goes on to say that it is possible there was a separate conversation with the Fort’s commander, Captain Delaplace that Feltham may not have heard. While we may never know for sure, it is unlikely there would be two different responses in such a short period and Feltham’s account is not tainted by any personal bias or gain. And his account makes sense given Arnold’s Massachusetts commission and Allen’s ties to Connecticut.

Duffy in “Inventing Ethan Allen” makes the same surmise though uses the same primary sources.

I am interested if you see any flaws in French’s analysis?

My comments were primarily for Jeff, to clarify the sequence of events and responsibilities, Arnold’s role, and to correct the perception that Allen couldn’t have uttered “Jehovah and the Continental Congress” because of his deism. Not only could he say them, he did, at least in “Narrative”, published 1779. But…

Allen had a tendency to make bombastic statements similar to “Jehovah and Continental Congress” (“The gods of the valleys aren’t the gods of the mountains”, etc.), so I think it likely that he did say something he thought would be suitably catchy – if not to Feltham then perhaps to Delaplace while Feltham was putting on his breeches. Maybe it wasn’t really a stand-out moment in anyone else’s mind because Allen was always making those sorts of comments and it simply didn’t achieve the dramatic weight he purported. While I think it likely that he did say something, particularly since none of the others present ever challenged his claim in “Narrative”, I’m not so sure that it was exactly what he put into print. Likely the wording he subsequently *claimed* in “Narrative” was developed through the course of his retelling the story over and over again until he got the wording which he put it in print. Of course that’s my personal view, and I’m careful to say that we don’t have a surviving account from anyone else that positively confirms or denies Allen’s claim.

In “The Taking of Ticonderoga” page 82 is a comparison of accounts. Feltham’s actual account is on page 44. Feltham does not quote either of them directly, but attributes a dialogue with Allen (including Allen’s sword over his head) and then says that Arnold engaged him in a more genteel manner. Feltham agrees with Arnold’s narrative in sufficient manner that I don’t think they are telling different stories, but his account paraphrases the dialogue and doesn’t give us a specific quote; so its not definitive on what Allen specifically said. Feltham does recount that the congress’ of both Massachusetts and Connecticut were mentioned, that afterwards he was shown commissions from both (interesting in that we don’t know of a commission that Allen would have had from Connecticut at that point in time). Feltham states that Allen demanded “immediate possession of the fort and all the effects of George the third” (Feltham’s paraphrased language, which of itself is fairly bombastic). While, as I said above, it can’t be ruled out that Allen used different language when subsequently speaking to Delaplace, I still think that “Jehovah and the Continental Congress” was too tightly turned a phrase for such a moment.

Since we forgive the John Paul Jones attributed “I have not yet begun to fight” as a paraphrase of what he actually said, and many other famous lines by others, I’m not so sure how critical we would be of Allen on this particular point.

In addition to French I’m also fond of Chittenden’s analysis published in the Vermont Historical Society papers around 1872. I think Chittenden lays out his case logically. There are only a few documents (like Saltonstall’s letter and Feltham’s account) which have been discovered since Chittenden wrote, so its worth a read. (sorry I don’t have the URL, but believe its available on line – French refers to it)

I also think the best quote of all is from Parson’s later letter, where he notes how amusing it is to observe various participants make claims, tell lies, and refuse to share glory which they all rightly earned.

Gene, sorry it took so long to respond. You make an excellent point on the Tories’ factor. The various parties involved were lucky to travel virtually unnoticed in some of those densely populated Tories’ towns. That being said, Arnold left his captains to recruit in Western Mass while he raced to the Catamount, and approximately 50 of them arrived by May 14. Enough to easily take the Fort under Arnold. Reinforcements wouldn’t have gotten there fast enough, but then Arnold wouldn’t have had the time to raid St. Johns and capture the British sloop of war along with the functional bateaux. (A grossly understated part of the overall Fort Ti capture by many historians) So it all worked out in the end.

With the Allen’s fabled surrender demand, I would say it’s more likely that Nathan Hale said his famous last words right before being hung. And the likelihood that Hale stated those last words is miniscule. Allen has a well-documented history in twisting the truth on so many occasions to fit his agenda, that I don’t see any basis to him saying it.

Well written Jim, you make some good points. However, I respectfully disagree with you on Allen’s quote. The quote came from Allen alone; someone that has been proven to fabricate his accomplishments, specific events, and even a book. (After more than half the book, “Reason, the only Oracle of man,” there’s a complete change in writing style and substance. The conjecture by some historians is that he plagiarized most of the book from his deceased mentor. I agree)

If the other prominent individuals there (Taking account that Mott, Easton, and Brown, may not have even been at the scene) had even heard the quote, they had their reasons not to dispute it. Four years later Allen was likely the furthest thing on Arnold’s mind. He had his documented problems with Reed in Philadelphia along with his long running battle with the Continental Congress. Not to mention since that point he had successes in Canada, Valcour, Ridgefield, Ft Stanwix, Saratoga, etc. that dwarf the raid at Fort Ticonderoga. It was a distant memory after losing it later to Burgoyne and getting it back again. He wouldn’t have cared. Allen’s military career, as documented exceptionally by Duffy and Muller III in “Inventing Ethan Allen” was two weeks in the CT militia, the raid (More like take-over) of Fort Ti, and the very brief/pathetic battle with Carelton’s men outside of Montreal. (He apparently fought with one soldier, using some acrobatic techniques by his own account) So basically nothing.

John Brown, James Easton, and Edward Mott, had all attached themselves to Allen early on. All three provided various self-serving accounts of the events to the Albany Committee, Massachusetts Congress, General Assembly of Connecticut, and/or Continental Congress to make Allen and themselves look like dynamic leaders and make recommendations for military commissions for each other. Arnold was bashed by Mott, and only mentioned in Allen’s account to the Albany Committee for obvious self-serving purposes.

As for Arnold being the originator, I didn’t state that. I did write “initiated”, which was maybe a poor choice of words on my part. So many people knew about the conditions and cannon/artillery at Fort Ti that it’s almost a moot point on who thought about a raid first. However, I do think the encounter with Parsons set events quickly in motion. See Parsons letter to his former classmate Joseph Trumbull, son of Governor Trumbull, written in New London, 2d June, 1775 (The Capture of Ticonderoga: Annual Address Before the Vermont Historical Society, Delivered at Montpelier, Vt., on Tuesday Evening, October 8, 1872, Chittenden, Lucius Eugene, pgs 100-101) https://books.google.com/books?id=-AELAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA29&lpg=PA29&dq=samuel+h+parsons+letter+to+joseph+trumbull+1775&source=bl&ots=Z-B9AEKVTJ&sig=BcdATldePEEjcDuReNOhBs1UV2Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CCoQ6AEwBGoVChMIuPLF_42YxwIVCHI-Ch1yfQVT#v=onepage&q&f=false

This excerpt from the letter tells us a lot: “On my way to Hartford, I fell in with Capt. Arnold, who gave me an account of the state of Ticonderoga, and that a great number of brass cannon were there. On my arrival at Hartford, Col. Sam Wyllys, Mr. Deane and myself FIRST undertook and projected taking that fort, etc.”

What would Parson’s motivation be to write that they first undertook taking the fort upon his arrival to Hartford to a confidant?

Really like this article! It was easy to imagine what it was like to be in Ethan Allan’s shoes. Tenuous circumstances all around him, dominated by uncertainty. I like the reference to his motivations evolving over time, as circumstances shifted. Ultimately his group that he represented were successful in surviving in challenging, and changing conditions. Well said Gene Procknow!

Gene, thanks for putting together a piece on Ethan Allen, perhaps THE most notable character of my home state. Having done some research on the period, I would like to add a few thoughts. Pardon the rather disjointed, minimal discussion of them. First off, most folks don’t realize that Vermont never claimed to be a republic. Like the other colonies cum states, they referred to themselves as a state with a republican form of government. The “republic” thing came later from outside. The “New Hampshire Grants” situation arose, in part, because New York initially did little as New Hampshire’s governor Benning Wentworth granted scores of charters. Even the king’s findings did little to clarify things as they had an element of vagueness (“shall be” interpreted as some time in the future) and the Crown did little to enforce them. New York had the most supporters on the east side of the Green Mountains. The “Arlington Junta” (Allens et al) came north from western Connecticut into western Vermont. There were far fewer than 10,000 regulars in Canada following the Burgoyne campaign. For quite some time, few Vermont residents knew of the negotiations. Allens tried to keep them secret. Ethan didn’t have it that bad as a prisoner. The British looked upon him as something of a celebrity and he often had parole to wander around. Other Vermonters certainly didn’t have it as well. Vermont had sympathizers in Congress but powerful New York prevented action on the Vermont question. Excellent, often overlooked point about the flow of trade from northern Vermont into Canada. Condition lasted until the opening of the Champlain-Hudson River canal in the first quarter of 19th century. Negotiations did not completely protect Vermont from British incursions. Many of the prisoners held by the British resulted from a raid into the Champlain valley and northern Vermont in the fall of 1780. Important point that Haldimand and the British did not trust Vermont’s intentions. The Allens failed to make any sort of real commitment to joining Canada. For those interested in further, primary source study of early Vermont, most volumes of the Vermont state papers are available through the Vermont Secretary of State’s office for $5-6 (http://vermont-archives.org/publications/publicat/index.htm).

Great presentation of the alternative viewpoints, Gene. I like your hint that Allen’s views were determined in part by circumstances, not fixed commodities. All historical figures need to be treated in this manner.

A new book on Allen has recently been published by the University Press of New England. While I have yet to read “Inventing Ethan Allen,” authors John Duffy and H. Nicholas Muller III have spent decades exploring Allen’s writings and writings about him so it should be a fine work. Rather than merely the story of Allen, the book is built around how collective memory created his story–or legend. To quote Muller, “We wanted to make it a story of how memory plays with people’s reputations, of how the mythology about Ethan Allen got started, and why.” I, for one, look forward to the read.

I am about 3/4 of the way through Nick’s and John’s book and it is a very interesting deconstruction of the Allen myth that so many have been indoctrinated into, and which still persists to this day.

As they conclusively show, Ethan Allen was hardly the honorable, altruistic man that history has painted him. Rather, he was consistently self-serving, self-promoting and highly opportunistic, not to mention downright mean on many occasions. His, and the Green Mountain Boys, depredations on the Yorkers are hardly the kinds of acts that warrant admiration, not to mention their drunkenness following the taking of Ft. Ti and which has been consistently overlooked in the rush to recognize him as a hero.

The blame for this is not only the way Allen promoted himself, but the complicit histories written by those in the mid-1800s seeking to identify a worthy hero on which to base Vermont’s early years. They did such a good job that those that might speak in contrary fashion were silenced, so history has simply repeated their misplaced representations of Allen’s worth.

Nick (who wrote a wonderful Foreword for my book coming out later in July, Insurrection, Corruption and Murder in Early Vermont) and John are wonderful people who have spent decades in studying these early years and I am very happy to see this kind of work being done to right past misrepresentations. It is long overdue.

Allen’s actions in life indicate that he deemed his first loyalty to people: family, friends, partners and customers ranked higher on Allen’s scale of responsibility than abstract entities like church or government. In addition to the 60,000 acres controlled by Allen’s family, the Allens and their partners in the Onion River Company controlled another 250,000 acres of New Hampshire land grants (including most of modern-day Burlington). As I’ve posted before, he owed great fiduciary responsibility not only to his family and partners, but also to those to whom he resold those grants. Allen’s sense of responsibility led him to champion their cause and the lens through which we view his activities must be hevily tinted by that perspective.

Brown’s reports upon his return from the Montreal trip state that the capture of Ticonderoga was preplanned with leaders in the NH Grants. While Peleg Sunderland’s participation points toward Allen, Sunderland and Hoyt also knew Warner, Chittenden, and other leaders of the Catamount cabal; suggesting the strategy was likely a result of group-think.

We tend to look at the capture of Ft. Ticonderoga as an isolated incident without the full context and should consider the 1775 Champlain Campaign not only as a “campaign”, but also through the context of Allen’s land-tinted lens. The majority, if not quite all, of the property controlled by the Onion River Company (BTW, for non-natives, that’s the original name of today’s “Winooski” river). The security of those grants and their prospertity was dependent on the security of Lake Champlain. The 1775 Champlain campaign did not stop with capture of Ft Ti, but importantly continued on to capture the forts at Crown Point and Saint Jean. Allen was overextended at St Jean and couldn’t hold it, requiring Warner’s command skill to succesfully extricate the Green Mountain forces. But; if Allen had been able to control St Jean long-term, and with it the control the Richeliue River connection between Champlain and the St Lawrence, he have ensured the security of his Onion River patents and the ownership rights of those to whom he sold them.

Allen’s lead role in preserving land patents made him ill suited to command the Green Mountain Boys as they transitioned from a provincial militia to a Continental Line regiment under New York command, leaving the election of Seth Warner much more logical choice for that role and left Allen to continue as champion of the land rights issue. Unfortunately, Allen still sought the glory of command which led to his ill-planned and undermanned attempt to capture Motreal and his capture. Meanwhile, Vermonters continued to play pivotal role in the Revolution, including pivotal roles delaying British re-capture of Ft Ti until 1777, the rear guard action at Hubbardton, and of course Bennington and Saratoga. By the time of Allen’s release the British once again controlled Ticonderoga, Crown Point, Saint Jean and Lake Champlian with numbers and alertness. With Warner the military commander of Continental line forces, Allen returned to the role of land patent champion

Well said, Jim. I agree with your assertions on Ethan Allen’s loyalties and economic incentives.

As you state, protection of land titles had to be of paramount importance to the Vermonters. Without clear land titles, their life’s investments in Vermont would be for naught. Further the Vermonters responded to Ethan Allen’s pamphleteering which was effective in making the political case why the land grants were legitimate. His writing helped build consensus for Vermonters to bind together to create a separate political entity. Allen was a more effective political than a military leader.

It is not too hard to envision the charismatic pull that Allen had on some (most definitely, not all) of his contemporaries and how later students of those times might credit him with altruistic behavior. However, as Muller and Duffy describe in great detail in Inventing Ethan Allen, the man had serious, serious credibility problems. For example, how to explain the egregious plagiarism of his oft-quoted Reason the Only Oracle of Man? ; his involvement in the “trial” and conviction of David Redding, which has all the trappings of a vindictive and wholly illegal hanging?; his involvement with the Haldimand Negotiations?; his conduct leading to his capture in Canada?; his self-promotion for rank?; “The Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!!!” and on and on….

Gene brings up the various sides of Allen in his article and, considering all that, together with recent scholarship, I tend to believe more than ever that while he was astute, he was also slick, opportunistic, self-serving, a friend to those he could dominate, and also bore a lingering, resenting grudge against those not allowing him to see his ambitions answered.

An interesting character, for sure, but hardly the hero that history has painted him. As Muller and Duffy conclude, “The real Ethan Allen does stand up, but few have seen him.” (pg. 208)

Gary;

I’m not particularly an Allen fan; and though I’ve not yet read “Inventing” can agree he was manipulative, often excessive and would add some speculator practices in Vermont to a list of shady character traits. But will rise to defend him on the two unjust charges of plagiarism and treason.

Allen clearly plagiarized; but that’s not a valid 18th Century character flaw. To convict Allen of plagiarism we’d have to also convict men like Paine and Jefferson who took equal liberties. As aghast as we may be now, 18th century authors actually did see imitation as a form of flattery; and men whose goal was to promote “ideals” were quite happy to see others promulgate by regurgitation their thoughts on religion, natural rights, and self-rule. Reverend Young, who died with his manuscript unpublished and unread, may not have complained about Allen’s subsequent rewrite for “Reason the Only Oracle of Man” publication because it got Young’s message out. After all, Allen was one of Young’s very few disciples.

The accusation of treachery in the Haldimand affair is a substantive issue. Going back to Gene’s original article, he asserts three possible alternatives for viewing Ethan Allen’s actions; I wish he’d included a fourth option of considering Allen as a VERMONT patriot. I advocate viewing events through a perspective which best explains “why” folks did what they did. In this case, Ethan Allen = land = Vermont.

Allen was instrumental in Vermont affairs from his days as a territory scout in the 1760’s through to his integral role in creating the Vermont Commonwealth. When Allen told Sherwood he had no intention of turning on his country he meant Vermont. Allen didn’t hold a military commission from the US. His military commissions rose from Vermont; elected as leader of the Green Mountain Boys and Brigadier General of the Vermont Militia at the time of the Haldimand affair. During the Haldimand Affair he was duly authorized by Vermont’s elected leadership (Governor Chittenden) to represent the Vermont nation in negotiations with the British and he fully reported his activities to those who tasked him (as well as Congress). He also transparently told his British counterparts that he’d passed letters and reports to Congress 1. Justus Sherwood’s journal records that Ethan made three things clear at the start of discussions which make his allegiance to Vermont plain 1) that no personal considerations could influence him, but as Haldimand’s proposals affected Vermont dearer to him than his life, he would convey them, 2) that Vermont be maintained as a separate self-governing province; and 3) that discussions would end if Vermont was recognized as a US state. 2 When discussions dragged on Sherwood reported to Haldimand that Allen’s purpose was simply to prolong the discussions and to scare Congress into admitting Vermont to the Union 3. William Kingsford’s account indicates Allen acted consistently in Vermont’s interest in representing Vermont’s predilection towards US statehood first, neutrality second, with reunification only a distant third option and only if the US Congress should choose to ignore Vermont independence and impose New York, New Hampshire and Massachusetts’ jurisdictional claims. 4

After Chittenden relieved Ethan Allen of the duty as lead Haldimand negotiator, in August 1781 the Vermont legislature conducted a hearing on the matter and concluded Ethan Allen:

“…had used his best policy by feigning or endeavoring to make them [the British] believe that the State of Vermont had a desire to negotiate a treaty of peace with Great Britain — thereby to prevent the immediate invasion [of Vermont] […] We […] think it a necessary political maneuver to save the frontiers of this state.” 5

There was obvious suspicion then, as now, that Allen acted in self-interest during this episode. However, in this instance it happened that what was good for Vermont may have also been favorable to Allen (and all other NH grant speculators, including Chittenden and Burling). In Allen’s first meeting with Sherwood they agreed on a truce for the duration of the negotiations.6 In the aftermath of coordinated British and British-led native raids on Royalton and Champlain shores, this was a critical achievement for the nascent state. Further, the negotiations were hardly secret. Allen forwarded letters and reports to congress, townships wrote petitions based on them, and topical correspondence between Henry Clinton and Haldimand was published in NYC papers. The knowledge of the negotiations spurred Congress and George Washington to tacitly acknowledge Vermont independence by pledging that Vermont would be admitted to the US once the technicalities surrounding New York jurisdictional claims were resolved. The NY legislature recognized Vermont in its vote to waive land-grant compensation as a barrier to Vermont’s admittance to the Union provided Vermont agreed to Congress’ definition of state boundaries – which enraged Governor Clinton despite Vermont’s immediate compliance with Congress bounds. 7 These were all major victories for Vermont, and while they set the stage insistent agitation by NY Gov. Clinton begat political hedging on the part of Congress who inexplicably tabled the issue of Vermont admission.8 The Haldimand affair brought Vermont to the verge of her goals; only to fail upon congressional mismanagement. Finally, since the Vermont legislature exonerated Allen, with far better view to the environment and facts of the situation than we can muster 242 years later, how can we now renew the charge?

We may not like any number of things attributed to Ethan Allen. We may not like that Vermont acted as an independent nation in its foreign policy affairs; but she acted within the right of nations and no differently than her sister colonies acted in establishing their own self-governance. We may not like Ethan Allen’s participation in those discussions, but must acknowledge he acted as a representative of his country, at the time an independent nation which he helped to forge. Though we may consider his activities contrary to the cause of the United States, technically Allen could not commit treason to the US since he was neither a citizen of that country nor its commissioned agent. As previously noted, the key to understanding Allen lies in the land, and the land was Vermont.

1. William Kingsford, “History of Canada: Canada under British Rule, Volume 7”, pgs 73-107, available as a free Google e-book)

2. Sherwood’s Journal as reprinted in Vermont History Quarterly, April 1956, at http://vermonthistory.org/journal/misc/JustusSherwood1.pdf and July 1956, at https://vermonthistory.org/journal/misc/JustusSherwood2.pdf

3. Record of the Vermont Legislature, as presented by Frederick Van de Water, The Reluctant Republic, New York: John Day, 1941, and The Countryman Press, 1974; p 269

4. Kingsford, pgs 73-107

5. Van de Water, p. 275

6. Reference both Sherwood and Kingsford accounts

7. Fingerhut, Eugene R, and Tiedemann, Joseph S., The Other New York: the American Revolution beyond New York City, 1763-1787, SUNY Press, Albany, 2005, pg 212

8. Van de Water, p. 294

Also see original correspondence within “Relations between Vermont separatists and Great Britain, 1789-1791”, S.F. Bemis, within “American Historical Review” Vol XXI, No 3, April 1916, pg 547-560, https://archive.org/stream/relationsbetween00bemi#page/560/mode/2up)

On the topic of land ownership, “Vermont’s First Settlers” by Jay Mack Holbrook; Vermont Office of Secretary of State.

Jim,

Nice review of some of the historiography surrounding Allen. Thanks.

Jeez, all I wanted to do was let folks know of the new book. Looks like there’s a latent desire in some to continue a discussion of the state’s early history.

In any case, here are a couple comments on the recent comments:

(a) We have all concentrated on Ethan’s role but, in the broader picture of land speculation, we can’t forget Ira. Without his participation, the Onion River Company would have been stillborn. Who knows where things would have gone without it.

(b) The Allens may have had an interest in 60,000 acres but they certainly did not control 250,000 at any time. That would have been about a sixth of the granted lands in Vermont. They sold off most of their early land holdings in order to fund the ORC. The company may have had 65-70,000 acres at its height.

(c) Ethan never captured St. Johns. He and his herd camped on the opposite shore and the Brits drove them off before they got to the fort.

(d) Another forgotten character is Remember Baker. He partnered with four of the Allen brothers – his cousins – to form the ORC. Baker surveyed my home town and wrote about crossing a field of rye just a few hundred feet north of my house. Too bad the Indians killed him so early in the war.

My acreage comment didn’t sit right with me so I double-checked. 250,000 acres is more like one-tenth of the granted lands. Sorry.

One more comment: Don’t think ill of Ethan for copying someone else’s writings. Everybody did it back then. I’m a big fan of period dictionaries and encyclopaedias and there are some that are nearly identical even though different folks claim authorship. Read Ray Raphael’s recent mythical post for another example much closer to home.

No! I didn’t mean that Mr. R. had plagiarized his piece. I meant that he included some material on copied writings. That’s what I get for trying to do this while in the midst of other things.

My Bad. 250,000 was an estimated acreage controlled by speculators throughout the state, and included both NH and NY grants. Its about 10% of the total state, closer to 20% of the state partitioned at establishment of the independent commonwealth in 1777, based on John Wentworth’s (Benning Wentworth’s son) estimate to the crown.

For a chart of acreage owned as of 1775 by the Onion River Company by town see James Benjamin Wilbur, Ira Allen – Founder of Vermont (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928), Volume II 522-525.

I write in the midst of travels abroad, from an iPhone, so will apologize in advance for poor formatting, spelling and lack of citations, but wanted to reply while the discussion is at least like-warm.

I take no umbrage at your respectful disagreement with the Allen quote, if you read my post carefully you’ll find that we agree. As I said, I think it unlikely that Allen made the exact statement he attributed to himself rather I believe it likely that he refined his statement over the course of repeatedly recounting the story until it became the phrase that he subsequently published. The actual point of my discussion was to contradict previous assertions that Allen did not make the statement and that he would not have made such a statement because of his deist beliefs, in fact Allen himself claimed the statement, it was not inserted into his mouth by a third party; and that the elements of the statement would not have been contrary to a deist perspective.

My next point was simply that taken in context of all available material, there is considerable evidence showing that the capture of Ft Ticonderoga and Crown Point was formulated far before any contact Arnold had with Parsons. Brown’s letter to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety from March 1775 tells us that the plan was already nascent as the New Hampshire Grant people were best suited for the task, had agreed to undertake it, and that a separate secret correspondence had been established for that purpose. Those who quote Brown’s letter often omit that critical portion. The Saltonstall letter not only reinforces that view, but demonstrates that Saltonstall had already developed the plan for the positioning of the Champlain cannon on Dorchester heights – the exact stratagem subsequently employed to force the British withdrawal from Boston. Your point that Parsons’ letter states they “first” made plans to mount an expedition is noted, but that may refer to the immediate actions they were taking, not that they had never before considered the proposition. Reading Parson’s letter we should be conscious that he is defending the colony by taking responsibility upon himself, lest another Colony take umbrage with the fact that Connecticut Committees of Safety had been planning to invade another colony without any consultation. Reading Parson’s letter in full may help with that context, see: https://books.google.com/books?id=MwQoAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA184&dq=samuel+h+parsons+letter+to+joseph+trumbull+1775,+connecticut+historical+society&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CD0Q6AEwBmoVChMI-r6c__XOxwIVxj4-Ch0CHABa#v=onepage&q=samuel%20h%20parsons%20letter%20to%20joseph%20trumbull%201775%2C%20connecticut%20historical%20society&f=false

On the question of whether Arnold was “smeared” by the reports tendered by the others present, we have to be objective. The first step in discounting this theory is to take a neutral look at the actual reports submitted by these men to assess whether Arnold’s contributions were falsely reported. They are not. Arnold is not credited with doing anything because he didn’t actually “do” anything — no contribution to the planning, assembly of forces, collection of supplies, collection of boats, advisement to other colonies, intelligence gathering, and any other contributions to the plan leading up to the capture of the fort. He appeared unexpectedly, made irrational claims for command, walked through the wicket. The fact that the reports are laudatory toward those who did contribute is not a smear of Arnold. What they do say regarding Arnold is that he unexpectedly appeared at the eleventh hour, presented himself to the committee of war acting at the behest of the colony of Connecticut, and asserted command based on a Massachusetts commission which he had not complied with. He had not assembled the regiment he was ordered to recruit; and arrived at the scene of the attack, on the eve of the attack, without a single man to command. The reports state that the Committee of War decided to stay its course: to act under the direction provided them by Connecticut and to base command authority on the basis of who had brought the most men. With Allen at 140 and Arnold at zero, Arnold was not a contender for command. In fact, the accounts tell us that Allen was not present when Arnold arrived; there was no actual confrontation between Arnold and Allen, rather it was between Arnold and the Committee of War (Allen’s account does not include this confrontation; correctly, since he was not there). Mott tells us that Arnold was not satisfied with that decision, and went off in search of Allen to once again demand command. The committee was afraid that Allen would acquiesce, and followed Arnold to ensure that Allen did not yield command. The reports of Arnold’s demand for the fort after capture are also told in factual manner: that he levied the demand, that the Committee of War acted under Connecticut authority to issue Allen a commission to command the fort until relieved by Connecticut authority. There are instances where the reports state that Arnold’s insistence on command was detrimental to the unity and morale of the men, and that Arnold should desist. That perspective appears to be true; and that upon receiving such reports Massachusetts sent Arnold orders to “play nice”; Connecticut sent Colonel Benjamin Hinman with a regiment to take over command; and the Ma delegation ordered Arnold to serve under Hinman, which he refused to do and resigned.

In comparison, consider that Arnold’s reports contain as many mis-statements, un-facts, self-embellishments as the others. He takes credit for tasks performed by others (raid the Skene manse), asserts command authority where he had none, and reports situations that simply were not true (Arnold states that the reinforcement of the British garrison at Crown Point led to the abandonment of the mission he ordered to capture it; yet at the time Arnold wrote the report Crown Point had already been captured by Seth Warner, which Arnold should have known if he’d been fully engaged). Arnold’s reports show not only a willingness to falsify his actions and embellish his image, but that he was out of contact with the actual command authority and at least partially in the dark regarding what actions were being taken and accomplished. Since you’re familiar with Lucius Chittenden’s work, I’ll let his evidence, arguments and conclusions stand for themselves on that account (Lucius E. Chittenden’s The Capture of Ticonderoga. Rutland, VT: Tuttle & Co., 1872, available as a Google e-book).

There’s no reason to say that any of the reporters were previously disposed to “smear” Arnold. Mott, Easton, Bull, Brown all went on to further the patriot cause and received laudatory compliments from future commanders (other than Arnold). Their ability and commitment is not in question from any other source. There’s no evidence that Mott had any previous acquaintance with Arnold or Allen, therefore the views formed by Mott were untainted by prior acquaintance. Subsequent to the Ticonderoga expedition, Mott proved time and again to be a reliable and effective officer and leader. Brown and Easton were both from Pittsfield, Ma. Easton was an ordained minister, leader of a congregation in Pittsfield, and also was elected the militia Colonel. It’s probable that Easton knew Reverend Young, Allen’s Deist mentor, as a neighbor and fellow pastor. Brown was a Captain in Easton’s regiment. Brown knew Arnold from familial ties – his sister was married to Arnold’s cousin, from the same family which took Arnold in and provided his apprenticeship. Brown also knew Allen since Allen’s wife and children lived near Pittsfield during Allen’s hostile confrontations with New York over the New Hampshire grants. He probably had met Allen in that context, and perhaps that formed part of the Massachusetts rationale for selecting him to reconnoiter Vermont and Canada in Feb-March 1775 – during which he certainly met with Allen in Bennington as is evidenced by Brown’s letter to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety and by Allen’s assignment of his Green Mountain Boy lieutenant (Peleg Sunderland) to act as Brown’s guide throughout his reconnaissance. At best you’d have to conclude that Brown knew them both. But, there would have been no reason for Easton, Brown and Mott to have had any discussion of Arnold on their march north towards Ft Ti – Arnold was not in the picture until he unexpectedly appeared Castleton on the eve of the assault. The best we could say is that Mott had no reason to smear Arnold, Brown had reason not to smear family, and Easton probably knew Allen but not Arnold; hard to build a conspiracy out of that.

As to the argument that Arnold little remembered Ticonderoga: no way. Absolutely, Arnold remembered and simmered over Ft Ticonderoga for the rest of his life. He cited it as an example of his unjust treatment, he cited it as an example of his leadership acumen, he fought with Massachusetts over his ill-kept receipts and accounting for payments, he was forced to respond to malfeasance and bad officership allegations made by Brown regarding both Ticonderoga and the Canadian expedition which Brown repeatedly re-asserted, charges that were referred to Congress and to which Arnold made a written reply (and which resurfaced during his court martial) and he maintained a personal vendetta against Brown and Easton, lodging accusations and aspersions against them on several occasions (on the Saint Lawrence, at Saratoga….). Arnold referred to Ticonderoga in his defection correspondence with the British, and after the war in correspondence to others. Curiously, he subsequently had little to say about Ethan Allen, which may go to the point that there never really was a direct confrontation between the two.

As to the plagiarism charge against Allen: yes, definitely he picked up Young’s work, completed it and published it. Times were different then and getting Young’s ideas out to the public, at the expense of his own time and money, is a credit to Allen. He was, after all, Young’s protégé and may have helped Young formulate his ideas and was a disciple until Young’s death. He didn’t plagiarize to get an A in class, he didn’t do it to make money, he did it to get the idea out to the public. “Reason” is perhaps Allen’s greatest work in life. Not because I like it, or believe that it’s solely his work, but because it’s one of the very few things he did totally for egalitarian reasons. Almost everything he did as a Catamount patriot and separatist was tainted by his personal motivations involving fortune (investments in land and speculation) and quest for reputation – a personal fault he shared with Arnold.

Jim and Jeff, insightful and discerning discourse on Ethan Allen’s fabled surrender demand at Fort Ti, planning for its capture, the treatment of Benedict Arnold and Allen’s Oracle of Reason book. There is a richness of his character which invites alternative interpretations as well as storybook myths.

For another view of Allen, see Robert Mello’s recently published biography on Moses Robinson. Mello’s portrays Ethan Allen as playing a lessor role in Vermont’s founding. Allen’s influence is especially diminished after his capture. Mello describes Allen’s falling out of political favor during the Haldimand Negotiations, essentially fading from public life. This is in stark contrast to Robinson who became Vermont Chief Justice, governor, legislator and U.S. Senator.

I highly recommend Judge Mello’s book for a balanced view on Allen’s contributions.

Well, I someone is taken an interest in the life of Ethan Allen. However, I have mixed views of him . One has to do with his hatred of Christianity and his blasphemous attacks on the Bible. Now I see that he was also a traitor as well. A reason why I once held with high regard was that he was no Benedict Arnold who was the most infamous traitor in American history. Now I see that I was wrong about Allen; as he was treacherous for self reasons much like Arnold reason’s for abandoning the American cause and joining the enemy that he once fought on the battlefield. Because he didn’t received the glory or money that he felt that he was owed.

I understand that since the Continental Congress refused to acknowledge Vermont as a state, Allen took it upon himself to negotiate land claims with Canada. This is a forum of treason and he had no right to do so without the authorization of the Continental Congress.

I have read the article by Gene Procknow with regard to this controversy. Procknow gives the main assessments attached to Allen and contends that he as a traitor. So I take that this can not be disputed. Allen the once firebrand who despised the British decided to change coats and work with enemy to recognize Vermont as separate province of the Great Britain.

I’ve read people’s comments and many defend Allen as being pragmatic and that patriotism is really not that realistic especially if your personal needs are not being met. Also he was being crafty with politics by putting both sides against one another. In particular I read Jim Gallagher who disputes the claim that Ethan Allen was a traitor and gives a lengthy explanation of why Allan was not a traitor. However, I remain unconvinced about the Vermont hero as not being a traitor as evidence proves that Allen was a traitor has he wised for Canada to recognize Vermont as part of the British domain. So I don’t understand why modern Americans are willing to celebrate a traitor to his country. Why are there statues of him and a museum as there are none for Benedict Arnold. Allen was much of a turncoat as Arnold was and that can not be disputed. People can try but there is no solid evidence the proves Allen was not a commit treason. Gallagher’s assertion that Allen acted with the interest of his fellow country is dubious. Allen’s primary reasons were selfish on behalf of himself and his family and not the people of Vermont. Mr. Gallagher also sites that Allen was not a traitor because he was not a citizen of the US or a commissioned agent . None sense Allen briefly held a commission with the debacle at Fort Ticonderoga. Also Allen was one of the earliest patriots who clashed with Tories and when things weren’t going his way he decided to sellout to the British as long as Britain recognize Vermont as independent province of his Majesty’s government. People who commit treasons do so for selfish- gain and Allen was a self-centered person and he not a hero of this country as people look at in that light.

Astute observations, David. After spending a great deal of time the past couple of years in the colonial court records of Vermont, NY and Mass. and various New England archives recreating Allen’s involvement in obstructing NY authority for my master’s thesis in military history (concentrating on the Rev War) called “A Heathenish Delusion: The Symbolic 1777 Constitution of Vermont”, I come out much as you and Gene did (available on request).

In fact, I treat Allen as engaging in treasonous conduct under the 1776 NY treason law after he returned from captivity and which was in place on the so-called NH Grants. He was a menace to NY settlers and a self-aggrandizing, selfish person looking out for himself and family and friends who were heavily engaged in taking land for themselves rather than constructively contributing to fighting on the behalf of the U.S. I also argue that the 1777 declaration of independence and constitution that the settlers created was a mask for all of their shenanigans. And while I have questioned some about removing his statue from the capitol’s portico, that will never happen.

Gary;

I’d enjoy reading your Heathenish Delusion.

Sure thing, Jim. Contact Todd or Don and they will give you my email address.