When Ethan Allen described his defeat and capture outside Montreal at Longue Pointe on September 25, 1775, he observed that “it was a motley parcel of soldiery which composed both parties.” The enemy included Canadian Loyalists, British regulars, Indian Department officers, and a few Native warriors. In the autobiographical A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen’s Captivity, Allen only provided the broad outlines of his own force, which “consisted of about one hundred and ten men, near eighty of whom were Canadians,” and he curiously described the rest as “about thirty English Americans.”[1]

Heavily reliant on Allen’s vague descriptions, with few other substantial sources to turn to, historians and biographers have often resorted to informed speculation as to who these Canadians and Americans were, and how they came to join Allen on his mission to take Montreal. Like many historical investigations, answering these questions has been analogous to solving a jigsaw puzzle missing many pieces, and without a reference picture. The digital age, however, has provided new pieces and shown new connections, producing a far more complete image of the men who fought alongside Allen in his last military battle.

Allen’s movements in the week before Longue Pointe form the puzzle frame. In September 1775, Ethan Allen was no longer the head of the Green Mountain Boys, who had recently been formed into a Continental regiment. He lacked a military command of his own and joined the invasion of Canada as a volunteer officer, with only an honorific title of colonel. Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler and Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery focused their Northern Army’s efforts on a siege of the well-defended British border post at Fort Saint Johns. Meanwhile, they sent Allen around the enemy fort and north through the Richelieu River valley to Chambly, to act as a liaison with Canadian Patriots and the Kahnawake Indian nation. He returned to headquarters after a successful first tour of several days’ duration. Then, on September 18, Allen was sent back out. Still a volunteer, any men with him were attached for specific duties or missions. A camp journal recorded his departure: “Colonel Allen with Captain Duggan and 6 or Seven men went off to Chambly in Order to raise a Regiment of Canadians.” This entry describes the first, smallest part of the “motley parcel” that would grow in the following week.[2]

The “captain” Jeremiah Duggan who left the camp with Allen is a key piece of the puzzle, as he connects many elements of the force that ultimately went to battle outside Montreal on September 25. Duggan was an emerging Richelieu Valley Patriot leader, second only to James Livingston that fall in directing Canadian irregular military recruiting and field operations. The Irish-born Duggan’s fifteen years of marriage to a Canadienne, and his few years as a wheat merchant in the lower Richelieu community of St. Ours, undoubtedly equipped him with essential French language skills and an important local network. None of the other men leaving headquarters with Allen on September 18 were specifically identified by name, but Pvt. Jean-Jacques Bourquin of the 1st New York Regiment was almost certainly among them. Captured with Allen a week later, the Swiss-born Bourquin would have been an obvious choice to be Allen’s French interpreter from the start.[3]

Tasked to help recruit Canadian irregulars, Ethan Allen’s initial destination was just a few miles from British-held Fort Chambly, at Pointe Olivier. There, at the north end of the Chambly basin, Canadian leader James Livingston had already assembled hundreds of locals in an armed camp. Allen did not specifically mention visiting Pointe Olivier in his own accounts,but a report from Livingston fills in this otherwise-blank section of the picture. The partisan “colonel” told Allen that there were a few weakly-manned British ships about forty miles away, sitting in the St. Lawrence off Sorel, vulnerable to capture by a surprise stroke in the character of his coup at Ticonderoga. Allen apparently took this on as a new mission, since Livingston told General Montgomery that he “sent a party each side of the [Richelieu] River, Col: Allen at their head” to take the ships. This intermediate mission connects more parts of the picture. Describing his continued trip down the Richelieu in his Narrative, Allen said “my guard were Canadians, my interpreter, and some few attendants excepted.” Other contemporary sources confirm that this Canadian core originated from Pointe Olivier, despite frequent historical speculation that Allen had recruited most or all of them himself. The “few attendants” were probably a small bodyguard assembled from Continental soldiers who had already been operating with the Canadians at the partisan camp, under the overarching command of Maj. John Brown. In numbers, these Canadians and Continental “attendants” are the most important part of the “motley parcel” puzzle.[4]

Contemporary sources further identify three partisan “captains” among Allen’s Canadians at the Battle of Longue Pointe. Based on their prominent positions in the Patriot partisan movement, Jeremiah Duggan and Augustin Loiseau almost certainly led the Canadian parties sent with Allen to capture the ships in the St. Lawrence. Like Duggan, Loiseau had been “stirring up as many of the Canadians as he possibly could” around his own home parish of St. Denis and was building a reputation as “a good soldier and staunch friend to America & its liberties.” Allen’s Narrative battle account mentioned a third Canadian leader, Richard Young—called a “captain” in one other Longue Pointe account—who curiously left no further documentary trace.[5]

In the Narrative, Allen did not mention the planned capture of British ships. He only said that he was “preaching politics” as he passed “through all the parishes” down the Richelieu to Sorel. During his lower Richelieu travels, however, Allen wrote his last letter to General Montgomery on September 20, from St. Ours, and confirmed that he had abandoned the ship-capture mission. Boasting that he had 250 Canadians with him, Allen also shared his intent to return to the Fort Saint Johns siege. He offered no explanation for his subsequent decision to continue north, toward the St. Lawrence, with his attached Canadians—away from his declared destination. After the St. Ours letter, Allen’s Narrative is the only first-person source for the rest of the mission. After reaching the mouth of the Richelieu at Sorel, he simply described following the shoreline southwest, “up the [St. Lawrence] river through the parishes to Longueil.” This baffling detour from Sorel to Longueuil has been another significant gap in the puzzle.[6]

An obscure document published in nineteenth-century Canadian sources seems to fill that void, though. On the night of September 22, Capt. John Grant of the Continental Green Mountain Boys Regiment wrote to Allen for help. Grant had received intelligence that a superior enemy force was preparing to attack his sixty-three-man detachment at Longueuil. He asked Allen “to send a party or com[e] as soon as ma[y] be[,] if not needed wh[e]re you now be.” Even though Allen never mentioned Grant’s plea, it offers a highly plausible reason for Allen to have led his force from the Richelieu Valley to Longueuil.[7]

Grant concluded his letter with another important line, that “Col. Leviston [James Livingston] hath just sent in an express hear and their is a party to our assistens on their march from Shambole [Chambly] expected this night.” This second party from Pointe Olivier was not initially linked to Ethan Allen, but he presumably would have met it when he arrived in Longueuil sometime on September 23. Allen’s Narrative and the primary source record are silent about who he actually met and what he did that night upon reaching Longueuil.[8]

The Narrative resumed on the morning of September 24 as Allen left Longueuil for La Prairie with a “guard of about eighty men.” These would have been his few American “attendants” and those Canadians under Duggan and Loiseau who elected to follow Allen even after he abandoned the original mission to capture the British ships on the St. Lawrence. Presumably, Allen intended to take them to the La Prairie-Saint Johns road, which would lead them on to the Northern Army siege camp.[9]

Just two miles out of Longueuil, Allen and his men encountered Maj. John Brown, who was directing numerous Continental detachments over a broad operations area along the southeast banks of the St. Lawrence and the lower Richelieu Valley. According to Allen’s Narrative, Brown and other officers persuaded him in private council to join a bold bid to take lightly-defended Montreal—the mission he fatefully accepted. Apparently, Allen rushed to execute the new plan without informing James Livingston of the scheme. Three days later, when Livingston finally received word of Allen’s defeat, he told General Montgomery, “Mr. Allen should never have attempted to attack the Town without my knowledge or acquainting me of his design, as I had it in my Power to furnish him with a number of men.” Clearly, none of the Pointe Olivier Canadian partisans had been attached to Allen with the intent to take Montreal.[10]

After meeting Brown, Allen described his return to Longueuil to “gather canoes,” and he added “about thirty English Americans” to his party there. These men have been an important, established part of the “motley parcel” picture, but their origins and connections with the others remained a significant mystery. There is still no direct documentary proof, but Captain Grant’s letter seems to provide the critical link—most of the thirty Continentals who joined Allen at Longueuil had probably come with the detachment sent by Livingston two days earlier to reinforce Grant. Some may also have been detached from Brown’s own marching party after the September 24 council.[11]

Assembling all these pieces of the picture, and shifting known elements around with likely connections, it appears that Allen’s force had three key components when he led it across the St. Lawrence to the Island of Montreal on the night of September 24-25. First were the few men directly connected to Allen’s September 18 departure from the Northern Army camp. The largest and most important contingent came from about eighty Canadian irregulars and a small Continental entourage, originally detached from Pointe Olivier to join Allen for the projected St. Lawrence ship-capture mission. The third component consisted of the thirty-some Continentals who joined him at Longueuil on the day before the battle—probably from the detachment that John Grant said Livingston was sending from Chambly (Pointe Olivier)

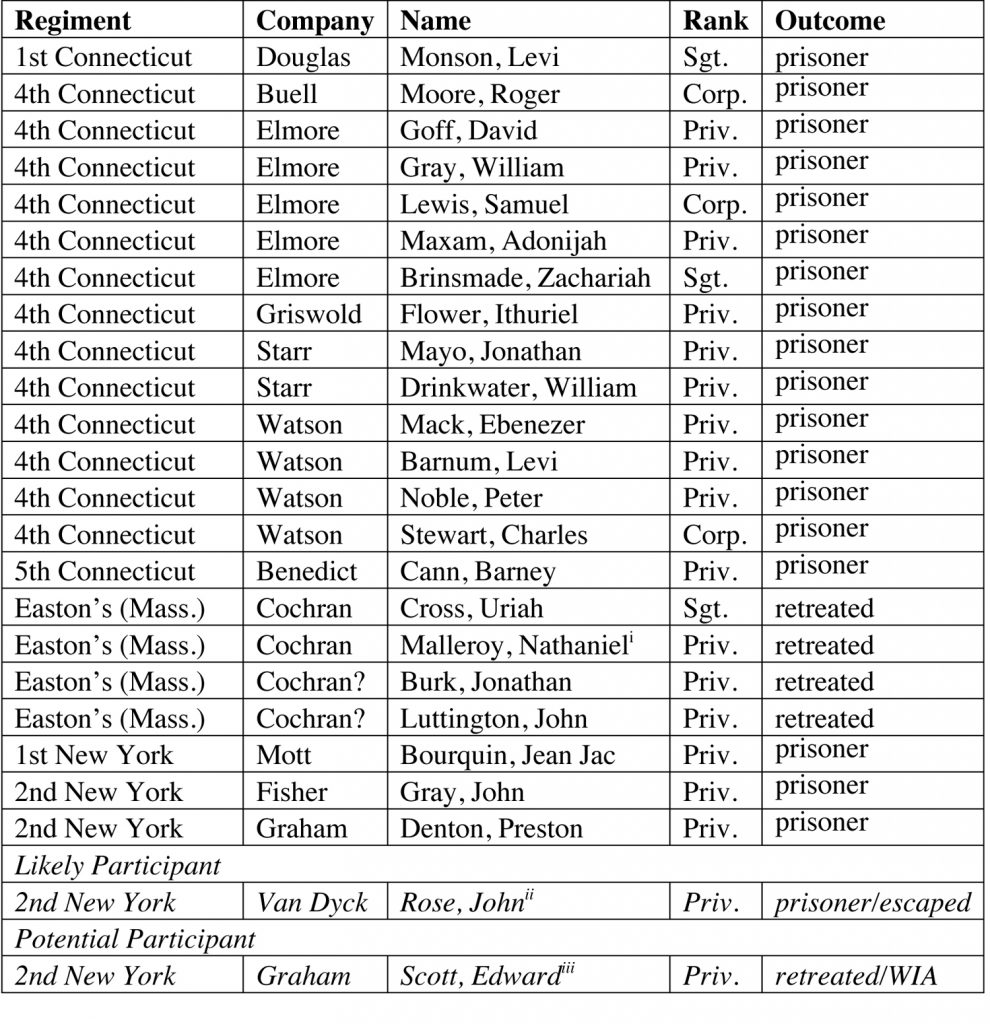

Table 1. American Contingent[12]

There are even more pieces of the puzzle that add detail and refine the image of these three main contingents. Two British lists of Longue Pointe prisoners describe specific members of the American contingent. Twenty-two are specifically identified by name—a large sample size from a group of about thirty. These men, all Continentals, were drawn from six different regiments. Thirteen came from the 4th Connecticut Regiment, up to four from James Easton’s Massachusetts Regiment, at least two from the 2nd New York, and there was one each from the 1st and 5th Connecticut, and 1st New York; but no more than five came from the same company. How did these seemingly odd, unconnected elements come together to form the American contingent?

The Americans’ apparently scattershot unit assignments are explained in Northern Army commanders’ tendency to rely on volunteers for dangerous missions away from the main camp—as documented in orderly books and pension narratives. Except for 2nd New York Regiment units that moved to La Prairie in late September, the companies listed in Table 1 all remained with the main army around Fort Saint Johns while detached volunteers roamed the Richelieu Valley and banks of the St. Lawrence. The high ratio of non-commissioned officers to privates—at least one to three—further indicates that these were volunteers or handpicked men. Early twentieth-century Allen biographer John Pell was broadly correct when he surmised that the Longue Pointe party’s Americans had “a diversity which indicates that the men had individually volunteered.”[13]

Two of the Americans also provided pension narratives that give hazy, but valuable, insight into their individual paths to Longue Pointe. Their accounts do not specifically explain how and when they joined Allen, but still fit within the established framework. Private Adonijah Maxam recounted his departure from the main camp outside Fort Saint Johns, beginning:

Capt. [John] Watson of Canaan, Capt. [Joseph] McCracken of the [2nd] New York troops and Major Brown went with a large party of men of whom I was one, for the purpose of penetrating thro the wood to Chambly in Canada. We lay at Chambly a few days & then I went to keep guard below Chambly [the Pointe Olivier camp]. Col Ethan Allen came to us there. We crossed the St. Lawrence River in the night with Col Allen a little below Montreal and while preparing breakfast the British force came upon us. We retreated & finally I was with Col Ethan Allen and others taken prisoner by the enemy.[14]

Maxam’s vague account seems to imply that he joined Allen near Chambly. He may have been one of the “few attendants” who joined Allen from Pointe Olivier for the initial ship-capture and recruiting mission on the lower Richelieu.

Another one of Allen’s Continentals, Sgt. Uriah Cross, wrote a pension account that was later published from a family-held manuscript. Cross described his departure from the main army camp as a participant in a fight on the night of September 17-18, at the crossroads immediately north of Fort Saint Johns: “I was now with Col Butler [Timothy Bedel] and Major Brown[’s] Regement who met a number of teams going to St Johns with provisions which was taken. Brown marched and took Cheamblee [Chambly].” His grasp of chronology had faded by the time this narrative was recorded in 1828, most notably in that Brown would not capture Fort Chambly until almost a month after Longue Pointe.[15]

From Chambly, Cross resumed: “I now with a number of others volunterd to go with Eathen Allen as our commander to take Montreal. We marched to longale [Longueuil] where we was met by the enemy and defeated.” Longueuil and Longue Pointe had merged into a single place in his distant memories. While Cross’s narrative gap between Chambly and volunteering to join Allen leaves room for interpretation, it is possible that he had been in the detachment sent from Pointe Olivier to reinforce Captain Grant at Longueuil, where he would become one of the thirty “English Americans” who joined Allen on September 24.[16]

The breadth of primary sources illuminates the American contingent’s diverse origins and varied paths to the ultimate assembly point at Longueuil. It is worth noting that even with all of the information now available about Allen’s Americans at the Battle of Longue Pointe, there is still no documentary evidence to support early Vermont historian Zadock Thompson’s suggestion that “Allen’s force was made up of Green Mountain Boys and Canadians.” If any Continental Green Mountain Boys participated in the operation, they were not only a minority, but they allmanaged to escape capture or death at Longue Pointe.[17]

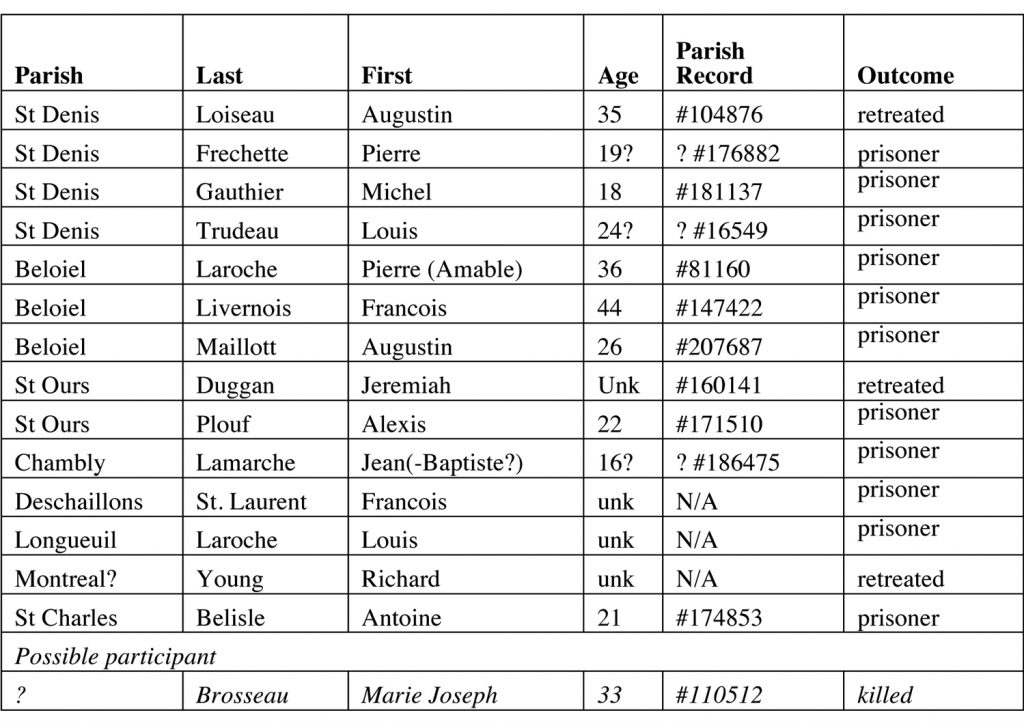

Table 2. Canadian Contingent[18]

In contrast to the reasonably well-developed picture of the American contingent, the depiction of the Canadians still lacks many pieces. Beyond leaders Duggan and Loiseau, the only meaningful source of information about specific Canadian contingent members comes from one British prisoner list, which identified eleven men taken with Allen. Nine of them came from lower Richelieu parishes between Chambly and Sorel, the heartland of the Fall 1775 Canadian Patriot uprising. Three dwelt in Loiseau’s home parish of St. Denis; one came from Duggan’s in St. Ours. Louis Laroche from Longueuil may have been a late addition to the force, perhaps joining at the canoe crossing to Longue Pointe. Burial records circumstantially suggest one more Canadian Patriot battle participant. Allen wrote that after his surrender, “the wounded were all put into the hospital at Montreal,” and on the day of the battle, Michel Joseph Brosseau died in the city’s General Hospital of the Gray Sisters.[19]

The relatively scant information gleaned from Canadian prisoner demographics still fits within the established framework of Allen’s path to Longue Pointe—with the vast majority of the men apparently being first attached to Allen from the Pointe Olivier partisan camp for the ship-capture mission. In any case, a sample size of just eleven or twelve Patriot Canadian fighters is too small to draw any firm conclusions about the seventy- or eighty-man contingent; it only depicts Allen’s Canadian die-hards—those who stuck with him to the point of surrender or death.

There are still many missing pieces and substantial gaps, but the partially-complete jigsaw puzzle picture that can be rendered from expanded, digitally-supported documentary analysis helps dispel some historians’ well-intentioned speculations and offers two key conclusions about Allen’s “motley parcel of soldiery” at Longue Pointe. First, the Americans were a composite contingent of volunteers drawn from several Continental units, attached to Allen at multiple points in his path to Longue Pointe. Second, most of the Canadians were sent from James Livingston’s Pointe Olivier partisan camp—undoubtedly under the immediate leadership of Jeremiah Duggan and Augustin Loiseau—following Allen as his mission evolved into their catastrophic attempt on Montreal.

[1]Ethan Allen, Narrative of Col. Ethan Allen’s Captivity (Albany: Pratt and Clark, 1804), 15-16, 19. The first printing was in 1779.

[2]Ethan Allen to Philip Schuyler, September 6, 1775 [sic], Peter Force, ed. American Archives, Fourth Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837-1846), 3: 742-43 (AA4); Allen, Narrative, 13; Benjamin Trumbull, “A Concise Journal or Minutes of the Principal Movements Towards St. John’s … in 1775,” Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society 7 (1899): 145 (manuscript available at Connecticut Historical Society, Diaries or journals kept by Benjamin Trumbull, 1775-1777, collections.ctdigitalarchive.org/islandora/object/40002%3A5088#page/1/mode/2up. For all applicable American Archives citations, the author also referred to copies in the Papers of the Continental Congress, RG360, M247, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

[3]Hector Cramahé to Earl of Dartmouth, September 24, 1775, Historical Section of the General Staff [Canada], ed., A History of the Organization, Development and Services of the Military and Naval Forces of Canada, From the Peace of Paris in 1763 to the Present Time (Quebec: 1919), 2: 81; John Livingston to Philip Schuyler, undated, AA4, 3: 743; Richard Montgomery to John Livingston, October 12, 1775, i41 v5 r50 p258, RG360, M247, NARA; Hugh Finlay to [Anthony Todd?], September 19, 1775, Richard A. Roberts, ed., Calendar of Home Office Papers of the Reign of George III, 1773-1775 (London: 1899), 409;Jeremie Duggan, individual #160141, Le Programme de recherche en démographie historique, www.prdh-igd.com/en/Acces(PRDH). See Bourquin’s information in Table 1.

[4]Allen, Narrative, 14-15; Allen to Montgomery, September 20, 1775, AA 43: 754; James Livingston to Schuyler, undated, AA4 3: 744; Simon Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire de l’Invasion du Canada par les Bastonnois: Journal de M. Sanguinet,” in Hospice-Anthelme Verreau, Invasion du Canada: Collection des Mémoires Recueillis et Annotes (Montreal: Eusèbe Senécal, 1873), 44, 49; “Quebec, September 28, 1775,” and “[Nauticus] To the Printer …,” Quebec Gazette, October 5 and 19, 1775; Hector Cramahé to Earl of Dartmouth, September 24, 1775, General Staff, ed., History of the … Military and Naval Forces of Canada, 2: 81. In his last letter to Montgomery, Allen boasted of his ability to raise hundreds of Canadians, and noted that they gathered fast as he ventured down the Richelieu, and his Narrative described that he “preached politics” on the trip and “met with good success as an itinerant”; but he never specifically claimed that he had recruited the 250 “Canadians under arms” with him at St. Ours on September 20.

[5]Allen, Narrative, 14-15, 19, 20; “An Extract of a Letter from Quebec, dated Oct. 1, 1775,” J. Almon, ed., The Remembrancer; or Impartial Repository of Public Events For the Year 1776, Part 1 (London: 1776), 136; John Graham Certification for Augustin Loseau, Albany, 3 May 1779; Augustin Loizeau Petition to John Jay, n.d.; John Brown Certification for Augustin Loizeau, May 6, 1779, i147 v3 r158 pp 407, 409-11, 413, RG360, M247, NARA; Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire,” 44, 49; “Extract of a letter from an officer of rank, dated Camp before St. John’s, Nov. 1, 1775,” Connecticut Courant [Hartford], November 20, 1775. Allen’s Narrative called Duggan “John Duggan,” and never named Loiseau, who was connected to the Longue Pointe force in Sanguinet’s journal.

[7]John Grant to Allen, September 22, 1775, The New Dominion Monthly (June 1870): 63 (cites original in possession of Montreal historian Alfred Sandham). The letter’s provenance is unknown, but it may have been seized from Allen after his capture.

[8]Ibid.; Allen, Narrative, 15.

[9]Allen, Narrative, 15; Allen to Montgomery, September 20, 1775, AA4,3: 754.

[10]Allen, Narrative, 14-15; https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/10/ethan-allens-mysterious-defeat-at-montreal-reconsidered/; James Livingston to Montgomery, September 27, 1775, AA4, 3: 953.

[11]Allen, Narrative, 15-16; Trumbull, “Concise Journal,” 146-47.

[12]List of the Rebel Prisoners put onboard the Ship Adamant, November 9, 1775, CO 42/34 fols. 255-56, (microfilm) Library and Archives Canada; “American Prisoners in Halifax,” Peter Force, ed. American Archives, Fifth Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1848),1: 1283-1284 (AA5). The author consulted local histories, Daughters of the American Revolution Lineage Books, and other minor sources for the most appropriate spelling of names. On the Halifax list Cann is identified as Barnabas Castle.

[13]September 10 and September 16 entries, 5th Connecticut Orderly Book, Early American Orderly Books, p25, 27, Reel 2, no. 17, (microfilm) New-York Historical Society; Cross, “Narrative,” 287-88; Petitions from Jonathan S. Alexander, W[no number], p4; Roswell Smith, S14490, p4; and Alpheus Hall, W19717, p9, RG15, M804, NARA; John Pell, Ethan Allen (Lake George, NY: Adirondack Resorts Press, 1929),117; David Bennett, A Few Lawless Vagabonds: Ethan Allen, the Republic of Vermont, and the American Revolution (Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2014), 83.

[14]Petition of Adonijah Maxam, W5345, p5, RG15, M804, NARA.

[15]Cross, “Narrative,” 280, 288. A second, later Cross narrative in government records only described serving with Brown around Chambly in the fall campaign, without mentioning Allen or Longue Pointe; Petition of Uriah Cross, S10499, p5, RG15, M804, NARA.

[17]Zadock Thompson, History of the State of Vermont: Natural, Civil, and Statistical, Part Second (Burlington, VT: Chauncey Goodrich, 1842), 35; Bennett, A Few Lawless Vagabonds, 83. Uriah Cross, and perhaps some others, had peripheral contact with the Green Mountain Boys in the summer of 1775, but none appear to have had an enduring association with the militia group.

[18]List of the Rebel Prisoners put onboard the Ship Adamant. In the Adamant list, Frechette is spelled Trichet, Maillott is spelled Mayotte, and Plouf is spelled Pluse. Parish Record numbers are from PRDH: Frechette, Trudeau, and Lamarche are possible parish record matches; St. Laurent and Louis Laroche do not have region-appropriate parish records matches. Belisle died as a prisoner off Cape Fear, NC in 1776; “American Prisoners in Halifax,” AA5, 1: 1283-84.

[19]Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire,” 44, 49; “[Nauticus] To the Printer …,” Quebec Gazette, October 19, 1775; James Livingston to Montgomery, September 27, 1775, AA4, 3: 953; James Livingston to Schuyler, undated, AA4, 3: 743-744; Bennett, A Few Lawless Vagabonds, 77; “Marie Joseph François Brousseau Brosseau,” individual #110512, PRDH; Allen, Narrative, 27.

9 Comments

I have an ancestor who claimed to be at both Ticonderoga and St. Jeans with Ethan Allen. He was a POW at Montreal 1779 to 1781. He was just 18 years old in the 1775 events. Very good article.

Very interesting! From my primary record searches, I have been able to identify very few men who participated in Allen’s St. Johns raid. As an aside, I’ve found the opposite for Ticonderoga. Just looking through veterans’ pension requests that mention Ethan Allen–with only slight exaggeration–there seem to be hundreds of men who claimed to have “been with Ethan Allen at Ticonderoga.” I have not delved deep enough into the question to validate or challenge any of those claims, but since many of those narratives did not specifically mention ‘taking the fort’, I am led to believe that lots of them arrived after Ticonderoga’s capture.

How pleased I was to see my Patriot ancestor listed among the American “motleys” – Roger Moore. I have been acquiring more information about him recently as the only story handed down to me was that he had slipped the handcuffs and escaped when he had been captured by the British. He had been shipped to England and Ireland and then returned to New York, housed in a church from which he escaped. This part of the story was probably relayed by Adonijah Maxam also on the list as recorded in the records of Salisbury, CT, when he was the oldest living “survivor of this band of sufferers” at the age of 88. Moore family records show 3 Union veterans, one of which was my Great-Grandfather Nelson Moore. Should you have any more information on Roger Moore I would be grateful to see that as well.

It is always inspiring to meet descendants of the historical actors in my research—especially of the soldiers who were doing all the hard and dangerous work in the field. Based on the scope of my ‘Ethan Allen at Montreal’ articles, my archival research on individual participants was limited so, unfortunately, I did not find any good primary source finds on Roger Moore. You are probably familiar, but Charles F. Sedgwick, A History of the Town of Sharon, Litchfield County, Conn, from its First Settlement (1842) https://archive.org/details/generalhistoryof00sedg describes the escape from New York by several of Allen’s men, including Moore and Maxam.

Awesome piece of history. Direct descendant from my Dad’s side of the family. Most of my cousins live in Michigan. Thank you Darrell!

Sorry I did not see this article earlier, Mark, but I am very glad to have found it.

As a minutia kind of guy, I am, obviously, quite pleased to get this information on these four 2nd New Yorkers from 1775. I do, however, have some concerns/questions.

John Gray was one of Capt. John Visscher’s “subscribers” and would have been a member of his Albany Provincial company. There is no roll to confirm he “shipped over” to Visscher’s company with the 2nd New York. Since your sources indicate the man was from Arlington, (presumably) Vermont, which is just over the border where Visscher recruited his company, I think you are on target.

The only issue is that there was also a John Gray list on the roll of Capt. Barent Ten Eyck’s 2nd New York Company. He enlisted on August 16 and deserted (went AWOL) on August 22. The question is if they are the same man or not? As of now, I have no information to clarify it. Do you have anything to put him with Visscher’s 2nd New York company?

Preston Denton, because of his uncommon name, is clearly the same guy listed in Capt. John Graham’s company. This is new to me, so am quite pleased to get this information.

John Rose, I already covered him here in my JAR article William Dickens, John Rose, and William Turnbull: Soldiers of the 2nd New York Regiment. So, support your conclusion.

Lastly, we come to Edward Scott. He was definitely in Graham’s company, but where is your source for him retreating from Montreal and being wounded in that action? I cannot find it in this article. As of January 1, 1776, I have him listed as being “lame in Montreal,” so something happened to him. I would like to just connect it up.

Thanks

Phil – thanks for checking on additional detail for these men, no surprise they’re of interest to you!

For John Gray the documentation comes from the two key prisoner lists. The earliest has his company as “Capt. Fisher” with his place of abode as “Narawaak” (List of the Rebel Prisoners put on board the Ship Adamant, Quebec, 9th November 1775, LAC CO 42/34, 255 [also Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 3: 458]); the other list says he is from Arlington, “American Prisoners in Halifax,” AA5 1: 1283-1284. Denton is on these same lists and is also mentioned in Our County and Its People, A Descriptive and Biographical Record of Saratoga County, New York (Boston, 1890), appendix, 27.

I didn’t notice until you commented, but the table notes didn’t make it into the published article.

Table note “ii” for Rose should be “In his pension narrative, John Rose stated that he was captured with Allen, but escaped when “he jumped over board from” HM Brig Gaspée, “swam ashore and again joined the army under Gen. Montgomery,” John Rose, S43940, p50, RG15, M804, NARA. See also Philip D. Weaver, “William Dickens, John Rose, and William Turnbull: Soldiers of the 1st New York Regiment,” Journal of the American Revolution (August 5, 2020).”

Table note “iii” for Scott should be “Circumstantially, Scott may have been at Longue Pointe. A compensation petition recorded that he was “wounded near Montreal on the 24th. of Septr. 1775 in his Right Shoulder.” Since there is no record of firefights in the area on the 24th, Longue Pointe is the most likely engagement where he would have suffered the wound; Report of the New York Commissioners of Invalids, 29 October 1789, in Kenneth R. Bowling, et. al., eds., Petition Histories: Revolutionary War Related Claims (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 7: 425.”

And even though it wasn’t part of your question, table note “i” was supposed to say “Malleroy, Burk, and Luttington are identified in Uriah Cross, “Narrative of Uriah Cross in the Revolutionary War,” ed. Vernon Ives, New York History 63 no.3 (July 1982): 288. There are no extant rolls of Cochran’s 1775 company, but limited evidence suggests that Burk and Luttington came from that unit.”

Thank you for the detailed reply and the plug for my article (also for the citation of my article – which I did not have handy when I wrote my comment). Glad you realized the error if the missing notes. Figured something like that had happened. Such things happen as technology will not always allow some things to carry over from one location to another.

I checked out both the Force and NDAR sources. I have a strong feeling that the Halifax list of American Prisoners in Force is the more accurate as to names and residence, but The NDAR list has the companies.

As there is no early roll for Benedict’s 2nd New York company, Barnabus Castle/Barney Cann, who lived in Saratoga, could very have been a member of that company prior to Ethan Allen’s Sortie into Montreal. With John Rose, your findings on Edward Scott, and one other man (who did not go into Montreal and avoided capture) makes a total of six 2nd New Yorkers who were involved. Great find – for me anyway! Thank you for your efforts.