Lt. General Earl Cornwallis, the British general officer commanding in the south, arrived at Petersburg in the morning of May 20, 1781, having marched from Wilmington, North Carolina at the close of the winter campaign. Under his command were his own corps of 1,780 men,[1] Major General Phillips’ (now dead) of 3,500, and a reinforcement of 1,700[2] currently arriving from New York. Opposed to him on the north side of the James River was a Continental corps of a little over 800 rank and file under Major General the Marquis de Lafayette, supported by militia. On June 10 it would be joined by about the same number of the Pennsylvania line under Brig. General “Mad” Anthony Wayne and on the 19th by 450 Continentals newly raised in Virginia by Major General Friedrich Wilhelm August von Steuben.

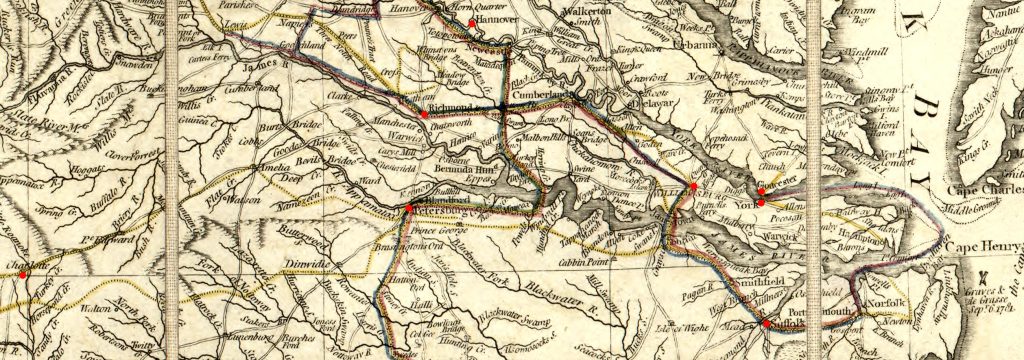

Cornwallis did not stay at Petersburg for long. Within four and a half days he had crossed the James River—two miles wide—at Westover, and while awaiting the passage of the bulk of his combined corps, he dispatched Major General Alexander Leslie, with a reinforcement, to command the garrison at Portsmouth. Then, having dislodged Lafayette from the vicinity of Richmond, he moved to Hanover Courthouse before crossing the South Anna River. Advancing slowly towards the Point of Fork, which lay some forty-five miles west of Richmond, he detached Lt. Colonel John Graves Simcoe with his Queen’s Rangers to destroy the arms and stores there while at the same time dispatching Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton and his British Legion on the Charlottesville raid to disturb the revolutionary assembly and also wreak destruction. Cornwallis played his part too, but not wishing to engage in further operations which might interfere with those of the British Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Henry Clinton, he retired gradually to Williamsburg to await his dispatches. He arrived there on June 25. As he retired, Lafayette had generally kept about twenty miles from him, but on the 26th a detachment of the enemy was repulsed when it attacked Simcoe at Spencer’s Ordinary. On the same date Clinton’s dispatches of the 11th and 15th arrived. Much to Cornwallis’s dismay they ruled out solid operations in Virginia during the sickly months of summer.

Threatened by a siege of New York, Clinton requested the return of 3,000 troops and artillery unless Cornwallis was minded to adopt Clinton’s ideas of operations in the upper Chesapeake (which Cornwallis was not). The rest of the troops Clinton desired to be used for defense, desultory water excursions, and the establishment of a station, preferably at Yorktown or Old Point Comfort, under cover of which “large ships as well as small may lie in security during any temporary superiority of the enemy’s fleet.”

On inspecting Yorktown and Gloucester, Cornwallis saw that it would require a great deal of time and labor to fortify them, both posts being necessary to secure a harbor for vessels of all sizes. Yet fortification was not an option, as assistance would have been wanted from some of the troops now being requisitioned by Clinton. And even if it had been an option, “they would have been dangerous defensive posts, either of them being accessible to the whole force of this province, and from their situation they would not have commanded an acre of country.” Under these circumstances he advised Clinton on June 30 of his decision to pass the James River and retire to Portsmouth that he might arrange the embarkation for New York.

On July 4 Cornwallis quit Williamsburg and three days later completed his crossing of the river from Jamestown Island. While waiting to pass, he had been attacked by Wayne but it was an inconclusive affair named after the Green Spring Plantation nearby.

On the 8th, while at Cobham, Cornwallis received Clinton’s dispatch of June 28. In it Clinton appeared to forget the threat to New York and announced his intention to raid Philadelphia. For this purpose he repeated his requisition of troops and artillery, to which he subjoined a requisition of vessels, twelve wagons, horses, and an engineer with entrenching tools etc. for 500 men. Cornwallis immediately advised Clinton that he would comply but went on to question the utility of a defensive post in Virginia. It is clear that he had Portsmouth in mind, as indeed is confirmed by Clinton in his reply of the 15th.[3] In Cornwallis’s eyes such a post “cannot have the smallest influence on the war in Carolina and . . . only gives us some acres of an unhealthy swamp and is for ever liable to become a prey to a foreign enemy with a temporary superiority at sea. Desultory expeditions in the Chesapeak may be undertaken from New York with as much ease and more safety whenever there is reason to suppose that our naval force is likely to be superior for two or three months.”

On the 9th Cornwallis began to march to Suffolk, where he expected to arrive in four or five days. From there he intended to send to Portsmouth the troops destined for the embarkation. As he began to march, he dispatched Tarleton on a raid to Prince Edward Courthouse and New London in Bedford County with orders to destroy supplies for Major General Nathanael Greene’s force (now in South Carolina) and to intercept any detachment coming from it. Tarleton marched hard but achieved little, as the supplies had been sent south a month or more earlier and no northward detachment had been made. He rejoined the troops in Suffolk fifteen days after his departure.

It was on July 12 that Cornwallis, now in Suffolk, received Clinton’s letters of May 29, June 8, June 19, and July 1. The first informed Cornwallis how much Clinton was displeased with his move to Virginia, but otherwise the first three letters were mostly superseded by Clinton’s of June 28, upon which Cornwallis was now acting. The fourth simply confined itself to the timing of the embarkation for the raid on Philadelphia. Cornwallis immediately replied, confirming that every exertion would be made to fit out the expedition in the completest manner without loss of time, and that, as apparently requested by Clinton, Leslie would accompany it.

Like a bolt out of the blue Cornwallis received at 1 a.m. on the 20th Clinton’s brief dispatch of the 11th countermanding his orders for the expedition, directing that Cornwallis remain on Williamsburg Neck or, if he had quit it, that he return should it be expedient, and desiring that at all events Old Point Comfort be held so as to secure Hampton Road. On the 21st Clinton’s dispatches of the 8th and 11th arrived stating his reasons, the gist of which was that Cornwallis had misinterpreted his intentions and that a station protecting ships of all sizes was so important on Williamsburg Neck that one should be possessed even if it occupied all the force at present in Virginia. He accordingly requested that Old Point Comfort be examined and fortified without loss of time and that, if it could not be held without possessing Yorktown, the latter be occupied too.

Clarity was not Clinton’s hallmark. As to his volte-face in countermanding his embarkation orders, there may have been other considerations besides the establishment of a station on Williamsburg Neck. On May 2 Clinton had just received a dispatch from Lord George Germain, the British Secretary of State, who stressed the importance of recovering the southern provinces and of prosecuting the war from south to north, made known his mortification at withdrawing troops from the Chesapeake, and conveyed the King’s pleasure that all available troops be employed on southern operations. He did qualify his remarks by adding that during the sickly months of summer troops might be withdrawn for offensive operations north of the Delaware, particularly on the Hudson or in New England, but such a dispensation excluded Philadelphia, which lay on the west side of the river.

On July 26 Cornwallis advised Clinton that he, his engineer and the sea captains had examined Old Point Comfort and that they all agreed it was quite unsuitable for a post to cover large ships lying in Hampton Road. “This being the case,” he continued, “I shall in obedience to the spirit of your Excellency’s orders take measures with as much dispatch as possible to seize and fortify York and Gloucester, being the only harbour in which we can hope to be able to give effectual protection to line of battle ships. I shall likewise use all the expedition in my power to evacuate Portsmouth and the posts belonging to it, but untill that is accomplished, it will be impossible for me to spare troops, for York and Gloucester from their situation command no country and a superiority in the field will not only be necessary to enable us to draw forage and other supplies from the country but likewise to carry on our works without interruption.” He had nonetheless gone some way in warning that they would be “dangerous defensive posts.”

Cornwallis occupied Yorktown and Gloucester on August 1 and 2, the evacuation of Portsmouth was completed on the 18th, and four days later he was joined by the remaining troops from there.

So was the scene set for the occupation of two places soon to be ignominious in British military history.

Bibliography

Ian Saberton ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, 6 vols (Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd., 2010)

Benjamin Franklin Stevens ed., The Campaign in Virginia 1781: The Clinton-Cornwallis Controversy, 2 vols (London, 1887-8)

[1]The figure is for all ranks.

[2]The figures of 3,500 and 1,700 are for effectives—an expression that excludes officers—and are given in Sir Henry Clinton’s letter of April 30. That they are for effectives is confirmed in his letter of June 11, where the combination of the two figures is revised to 5,304.

Recent Articles

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

The New Dominion: The Land Lotteries

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

Recent Comments

"Hero to Zero? Remembering..."

I did come across this record, it adds a little bit: He...

"Hero to Zero? Remembering..."

How did Gates's son Robert die? I have not been able to...

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...