Alexandria, Virginia, is well known as George Washington’s hometown, but its role during the American Revolution is not widely understood. Like the rest of Northern Virginia, Alexandria was largely spared the fierce warfare that raged across the country. Nonetheless, the Revolution profoundly affected the community. Founded in 1749 along the Potomac River, Alexandria was a young seaport when the Imperial Crisis commenced in 1760s. Beginning with the Stamp Act, Alexandria’s leaders were actively involved in opposing British policy. After the Revolutionary War began, Alexandria was constantly in alarm, fearing the British Navy, Loyalist subversion, and Indian attacks. Alexandria became a base for inoculation of Continental soldiers, forcing residents to contend with the additional threat of disease. Black Alexandrians took advantage of the war, joining both sides in their quest for freedom. In 1779, Alexandria replaced its oligarchic and unelected government system with a more democratic structure that made community leaders responsible to the people. Alexandria shows that even for those communities far from the front lines of war, the Revolution brought fear, chaos, uncertainty, and societal change.

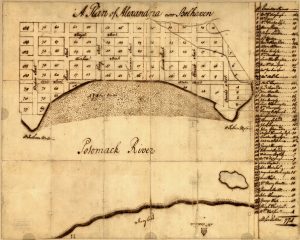

Although John Smith explored the Potomac River in 1608, it was not for another one hundred years that there was substantial white settlement in Northern Virginia. In 1732, a tobacco inspection warehouse was built at the future site of Alexandria, which was followed eight years later with a ferry bridging Virginia and Maryland. By 1742, the population had grown enough that the Virginia General Assembly created Fairfax County from the northern part of Prince William. Some Scottish merchants settled around the tobacco warehouse and the settlers began calling the community Belhaven. In 1748, planters and merchants, including Lawrence Washington and Lord Thomas Fairfax, petitioned that a town be established at the site of the warehouse, wanting it to be a marketplace for exporting local produce and importing British manufactured goods. In May 1749, the Virginia House of Burgesses approved the petition, and the town came to be known as Alexandria. The community grew into a substantial seaport, with a population of about 2,000 in 1775. Although tobacco had long been the dominant crop in Virginia, many planters had switched to growing grains by the 1760s, and wheat was the most common commodity exported from Alexandria. Gen. Edward Braddock made his headquarters in Alexandria during the French and Indian War, and his army departed the town on its ill-fated expedition against Fort Duquesne.[1]

During the Imperial Crisis, Alexandria’s community leaders opposed Parliamentary taxation. In 1765, George Johnston, one of Fairfax County’s members in the House of Burgesses and a resident of Alexandria, supported Patrick Henry’s controversial Virginia Resolves. These resolutions outlined Virginia’s opposition to the Stamp Act, arguing that Virginians could only be taxed by their elected assembly. Johnston seconded each resolve Henry introduced to the assembly, and he may have even aided Henry in writing the resolves.[2] John Carlyle, a prominent merchant and the wealthiest man in the community, supported the resolutions passed by the House of Burgesses in 1769 objecting to the Townsend Acts. He also backed Virginia’s nonimportation agreement, saying that with economic pressure, there was “no doubt the Revenue Acts Will be Repealed, & then we shal be in our former State of Dutiful & Loyal Subjects.”[3] Harry Piper, another merchant, described the Townsend Acts as “very unjust.”[4] In June 1770, Virginia created a stronger nonimportation agreement, establishing committees of inspection to ensure that no merchant imported prohibited goods. If a merchant defied the agreement, the committee would publish their name in the papers and encourage others to break ties with the violator.[5]The Alexandria Committee of Inspection consisted of George Washington, George Mason, John Dalton, Peter Wagener, and John West. Yet just as Virginia implemented this new boycott, news arrived that Parliament had rescinded all the Townshend duties except the one on tea. Northern cities began abandoning their nonimportation agreements. Alexandria continued to enforce the boycott, but by 1771, many merchants were openly violating nonimportation. The Alexandria Committee remarked in July that nonimportation had been “dropped by all our sister colonies, except refusing to import tea” and suggested that Virginia follow their lead. Later that month, Virginia restricted its boycott to tea.[6]

Alexandria became radicalized against British rule in 1774. Many colonists were outraged at the Coercive Acts, which Parliament passed to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party. The port of Boston was to be closed until the destroyed tea was repaid, and Massachusetts’ colonial charter was annulled. Gen. Thomas Gage also arrived in Boston as military governor with an army under his command. Although the Coercive Acts only applied to Massachusetts, the other colonies feared that Britain would eventually punish them with similar measures. Following the example of Baltimore, Alexandria established a committee of correspondence in May. Consisting of ten men, it was to communicate with committees in nearby towns to organize opposition to British policy. In a letter to Baltimore, several committee members regretted that Boston was experiencing “the Lash of arbitrary power” and said that Boston’s plight was “the cause of all America.”[7] The House of Burgesses had designated June 1 as a day of fasting and prayer, which was observed in Alexandria with “uncommon Solemnity.” Alexandria and Fairfax County also raised money and provisions to support those in Boston economically devastated by the closure of the port. By early July, the county had raised 273 pounds sterling, thirty-eight barrels of flour, and 150 bushels of wheat.[8]

That same month, a committee consisting of a few men, including George Mason and George Washington, drafted twenty-four resolutions called the Fairfax Resolves. Mason was the primary author, but Washington chaired the meeting of Fairfax County freeholders in Alexandria that approved the resolves. The resolutions argued that the colonies had the right to govern their internal affairs and that Parliament could not tax them without their consent. They also criticized Britain’s punitive treatment of Massachusetts and recommended a boycott on British goods. The resolutions additionally called for colonial unity and the permanent abolition of the slave trade. If Parliament refused to repeal the Coercive Acts, they warned “there can be but one Appeal,” meaning an appeal to arms. Many other Virginia counties also issued resolves, but Fairfax’s were the most radical and influential.[9]

Not all Alexandrians approved of the escalating resistance to British rule. Bryan Fairfax was conflicted about what course of action Virginia should take. He acknowledged that Parliament was encroaching on their liberties, but worried that colonists were embracing radical positions. Fairfax opposed Parliament’s alteration of Massachusetts’ charter, but he had no objection to the closure of the port of Boston if Britain reopened it when the tea was repaid. He also questioned the claim that the colonies could not be bound by any law of Parliament, saying there “never was an Act of Parliament disputed ’till the famous Stamp Act.”[10] Nicholas Cresswell, a young Englishman, was much less conflicted than Fairfax. In October 1774, he described Alexandria as being in “the utmost confusion.” Cresswell blamed New Englanders and Presbyterians for dragging the rest of the colonies into rebellion. On November 1, Cresswell went to an Alexandria tavern to hear the resolves of the First Continental Congress and their petition to the king. Unimpressed, he said both were “full of duplicity and false representation.” Later in the week, Cresswell witnessed townspeople shooting an effigy of Lord North before parading it through the streets and setting it on fire. On November 6, he attended a Presbyterian meeting, only to find that the parishioners were “rebellious scoundrels” more interested in politics than religion.[11]

Alexandria enforced the Continental Association, which had been established by the First Continental Congress. The Association called for the nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation of goods between the colonies and Great Britain, Ireland, and the British West Indies. Nonimportation began on December 1, 1774. Because news of the policy would take time to travel overseas, merchants whose imports arrived before February 1, 1775 would be reimbursed so they did not lose money. In mid-December, the Hope arrived from Belfast with Irish linen. The merchants who had imported the linen reported its arrival to the Fairfax County Committee, who ordered it to be sold on December 24. The merchants were reimbursed for the “cost and charges” and the profits of the sale went to support Boston. In March 1775, a merchant tried to sell salt in Alexandria in violation of the Association. The Fairfax County Committee subsequently wrote to the Baltimore Committee, asking that any merchants who went from Baltimore to Alexandria be given a certificate from a committee member certifying that their cargo was imported within the time allowed by Congress.[12]

As tensions escalated throughout Virginia, Fairfax became the first county to establish an independent company of soldiers. In September 1774, George Mason chaired a meeting of Fairfax gentlemen and freeholders. They resolved that it was a “Time of extreme Danger, with the Indian Enemy in our Country, and threat’ned with the Destruction of our Civil-rights, & Liberty.” The men feared that Royal Governor Lord Dunmore would employ Indians against them. They agreed to form into a company called the “Fairfax independant Company of Voluntiers,” not to consist of more than one hundred men. The gentlemen would drill, learn proper military exercise, and remain ready in case of “hostile Invasion, or real Danger of the Community.” Independent companies began forming across the colony. The companies were primarily for gentlemen and would give them the necessary experience to be military officers if war broke out. Fairfax County later established a Mechanic Independent Company alongside the gentlemen. In March 1775, Nicholas Cresswell witnessed Washington drilling the men in Alexandria. The gentlemen wore buff and blue, and the mechanics red and blue. There were about 150 in total, and Cresswell said they made “a formidable appearance.”[13]

After the war began at Lexington and Concord, there were fears about the vulnerability of Alexandria to enemy attack. Loyalist John Connolly exacerbated concerns in the town. In September 1775, the Virginia Committee of Safety captured proposals that Connolly had given to General Gage in Boston. Connolly suggested that he go to the frontier and recruit Ohio Indians, French settlers, and militia to subdue the rebellion in Virginia. He would promise the militia three hundred acres per man if they joined him. After gathering recruits, Connolly would attack Virginia from the west, advancing to Alexandria, where he would rendezvous with Lord Dunmore in the spring of 1776.[14] Connolly considered Alexandria an important crossroads, by which communication between the North and South could be stopped. One of Connolly’s neighbors also warned that he intended to “proclaim freedom to all convicts and indented servants” on his march. Fortunately for Alexandria, Connolly was captured in Maryland while traveling to Detroit to enact his plan.[15]

Even with Connolly imprisoned, fear of Dunmore remained. In January 1776, Alexandria flew into panic. On January 17, Lund Washington noted that Alexandrians heard rumors of British ships on the Potomac and expected their town to be burned. Two weeks later, he wrote that the town was in chaos again on a similar rumor. He reported that “the Women & Children are leaveg Alexandria & Stowg themselves into every little Hut they can get” and that wagons were bringing goods out of the town. The militia had been called up, but very few had firearms.[16] In the midst of this winter chaos, Alexandria began to embrace the idea of independence from Britain. Nicholas Cresswell said that “Nothing but Independence talked of” and that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was widely read, although he called it “One of the vilest things that ever was published to the world.”[17]

Authorities began taking steps to protect the community from attack. The militia built small breastworks at each end of town armed with a few artillery pieces. The Virginia Committee of Safety ordered that a signal system be established along the Potomac from the mouth of the river to Alexandria which could notify locals if British ships were approaching. In September, the Virginia Council approved a petition from Alexandrians asking that they be allowed to purchase sixteen iron cannons. These would be erected on batteries in the town and defend the community from a seaborne attack, but it does not appear they found sixteen cannons to purchase.[18] The Alexandria Committee and Maryland Council also agreed to come to each other’s aid in the case of emergency. The Virginia Council of Safety tasked John Dalton and George Mason with the construction five vessels which would form the Potomac Flotilla. The men purchased three civilian sloops, turned them into armed cutters, and began building two galleys. The fleet’s flagship was the American Congress, a converted sloop with a crew of ninety-six men. Mason and Dalton raised marines for the ships and acquired ten barrels of gunpowder from the Maryland Council of Safety. Lord Dunmore entered the Potomac River in July 1776, and advanced to within twenty-five miles of Alexandria. Although this incursion again alarmed the town, he soon left the Potomac.[19]

Alexandrians were also frightened by Loyalist activity within the community. One event in 1777 gave them considerable alarm. Nicholas Cresswell and another Loyalist, Colin Keir, gave arms and ammunition to prisoners in Alexandria so they could escape. The prisoners were to meet Cresswell and Keir further down the Potomac at Cedar Point, where Cresswell would bring a boat to carry them to British ships. On the night of April 25, the nine prisoners escaped, crossed over to Maryland, and began traveling south to Cedar Point. Their guide was Thomas Davis, a local Loyalist. Bad weather prevented Cresswell from meeting them at Cedar Point, and two men in the group, including Davis, returned to Alexandria. Those that continued walked through the woods to stay hidden. When they reached the Chesapeake, they took a boat across to the eastern shore, and then traveled overland to Delaware Bay. There, they stole a boat and reached the safety of a British warship that brought them to New York City. The prisoners’ breakout sent Alexandria into panic. Rumors quickly spread that the Loyalists had intended to burn the town. A Philadelphia merchant passing through Alexandria remarked that “Some Tories lately formed a Plan for burning Alexandria & murdering the Inhabitants.”[20] When Davis returned to Alexandria, he confessed the names of several townsmen who helped facilitate the escape of the prisoners.[21] Seven men were sent to Williamsburg for trial. Davis and four conspirators were convicted of treason for aiding the enemies of America, but the judgement was arrested on a technicality. The prosecutor had apparently not specified who the enemies of America were, and the judges overturned the jury verdict of guilty, releasing the prisoners. John Parke Custis, George Washington’s stepson, complained about the acquittal, saying that “It is now determined that releaseing Prisoners of War, from their Place of confinement, is not Treason against the State.”[22]

As a crossroads between north and south, Alexandria was chosen as a smallpox inoculation center for the Continental Army. Soldiers from the South traveling north stopped for inoculation. Town residents were also inoculated. In April 1777, George Mason remarked that the “whole towns of Dumfries and Alexandria are under innoculation for the small pox, in the latter about 600 persons.”[23] That same month, Nicholas Cresswell said “Such a pock-eyed place I never was in before.”[24]Smallpox inoculation interfered with the scheduled election on April 21 for Fairfax County’s representatives to the Virginia House of Delegates. Fairfax freeholders petitioned the House of Delegates, saying that they did not visit Alexandria to vote because “the smallpox then raged in the said town.” Only sixty of three hundred eligible voters cast ballots. The petitioners requested a new election, but the House rejected their petition.[25]

Dr. William Rickman, the director of Continental hospitals in Virginia, faced criticism for his management of inoculated soldiers in Alexandria. Twenty men died under his care. Believing that the hospital was not well managed, several Virginia and North Carolina officers accused Rickman of negligence. Congress suspended Rickman in December 1777 and launched an investigation of his conduct.[26] The Medical Committee spoke to soldiers and other witnesses. In March 1778, the committee concluded that although the soldiers in Alexandria suffered more than in other places, it was not Rickman’s fault. The hospital had been poorly supplied, the soldiers had few clothes, and the men were exhausted from long marches before arriving. The committee added that most who died perished from putrid fever, not smallpox, and that one of Rickman’s assistants had “greatly abused the confidence and trust reposed in him by the director.” Rickman was acquitted and returned to work.[27]

Africans and African Americans took advantage of the wartime turmoil in Alexandria. Blacks comprised a large minority of the town, at 22 percent in the 1790 census. Some black Alexandrians thought their best chance of gaining freedom was with the British. In 1775, Lord Dunmore had issued a proclamation offering freedom to slaves capable of bearing arms who were owned by Revolutionaries. The proclamation frightened and enraged white Virginians. Harry Piper called Dunmore’s Proclamation “a Species of cruelty hardly to be paralleled.”[28] In September 1777, an enslaved man named Jack fled from his master, William Herbert. Jack had traveled with his previous owner to New York, when his master was in the army, and Jack would have likely seen black soldiers. Herbert said that he expected Jack would “endeavour to get to the enemy at this time.”[29] Two years later, an enslaved man named Ishmael absconded from his master William Hepburn, an Alexandria merchant. About thirty years old, Ishmael was a ropemaker. Hepburn warned that Ishmael might try “to get on board some of the enemy’s shipping.”[30]

Other black men in Alexandria supported the Revolution. Desperate for manpower, free blacks were generally permitted to serve in the Virginia Line. John Pipsico enlisted in the 3rd Virginia Regiment in September 1780 and remained in the service for two years. He fought in numerous battles across the South, seeing combat at Guilford Courthouse, Eutaw Springs, Hobkirk’s Hill, and Ninety-Six.[31] Because free blacks could enlist, many enslaved Virginians ran away and joined while pretending to be free. In response, the legislature required that black men have a certificate of freedom, but runaways still tried to join the Continental or state troops. Charles Jones posted a runaway slave advertisement in September 1777 for his enslaved man named Joe, who he believed planned to “enlist as a freeman.”[32]

Alexandrians changed their governing system during the war. Since its establishment, Alexandria had been governed by an unelected board of trustees, dominated by the wealthiest men in the community. In 1779, residents petitioned the House of Delegates, asking that their community be incorporated. The petition was approved, and the trustees were replaced by a mayor-council system where freeholders elected men to serve on the Board of Alderman and a Common Council. The council elected one of its members as mayor. Although wealthy merchants and planters would continue to hold the positions, the new system gave Alexandria greater autonomy and made community leaders much more responsible to the people than they had been previously.[33]

The closest Alexandria came to being attacked was in the spring in 1781. British vessels again entered the Potomac River, but this time they sailed all the way to Alexandria. Loyalist privateers under the command of John Goodrich were also active, and they plundered homes on the banks of the Potomac below Alexandria, kidnapping some men and welcoming slaves to their ranks. On April 1, a tender belonging to a privateer called the Trimer came into Alexandria harbor in the night and tried to seize a vessel full of tobacco. The Loyalists were seen, and armed vessels followed them as they fled. After about forty miles, the Loyalists were captured. One of the prisoners claimed that, had they succeeded, they would “have burnt Genl. Washingtons Houses, [and] Plundered Colo. Mason.”[34] In response to the British and Loyalist threat, some men went to Annapolis and brought several cannons overland to Alexandria. Gov. Thomas Jefferson also ordered the construction of a battery, a redoubt, and a blockhouse which could hold fifty to eighty men.[35]

Before Alexandria even began building these new fortifications, three crown ships appeared off the coast of the town. Among them was the Savage, a sloop-of-war which had just threatened Mount Vernon. Several of Washington’s slaves joined the ship and the crew burned houses in sight of Mount Vernon on the Maryland side of the river. Alexandria was reported to be “in much confusion” but local militia began turning out in significant numbers to turn back any landing.[36] The militia did not dare to fire their cannons on the ships, knowing their defenses were “too weak to withstand the force of the enemy.” Probably not wanting to confront a large body of militia, the British instead landed across the river in Maryland where they were “met with spirited opposition.” Not long after this skirmish, the ships sailed back down the Potomac and away from Alexandria.[37]

Though Alexandria would never be seriously threatened by enemy forces again, its war continued. When the Marquis de Lafayette marched through the town on his way to reinforce American troops near Richmond, he impressed some wagons for the use of his army. Locals also began building the fortifications outlined by Jefferson, and by May 1781, they had completed part of the battery and mounted three guns on traveling carriages.[38] During the Yorktown campaign, most of the allied army went by water down the Chesapeake, but the supply wagon train traveled overland through Alexandria. In the summer of 1782, the French army left Williamsburg and headed north for New York, stopping in Alexandria along the way. One observer noted that “young ladies of the neighbourhood danced with the officers on the turf in the middle of the camp.”[39] George Washington came home in December 1783, and was congratulated by Alexandrians on his “return from the conclusion of a glorious and successful war.” After years of widespread fear and uncertainty, the war was over.[40]

Although it never experienced the bloodshed of many towns, Alexandria helps show how the Revolution fundamentally affected even those communities distant from the main theatres of war. The community continually feared the arrival of British warships, sending the town into chaos and forcing them to organize defenses. With the town a smallpox inoculation center, Alexandrians faced the threat of disease. Both free and enslaved blacks took advantage of the war’s upheaval and partook in the conflict. Citizens also introduced an elected government during the war. As the world focused on its most famous resident, the American Revolution profoundly shaped Alexandria and its inhabitants.

[1]Donald G. Shomette, Maritime Alexandria: The Rise and Fall of an American Entrepôt (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2003), 9-15; Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1742-1747, 1748-1749 (Richmond: The Colonial Press, 1909), 405.

[2]“Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Patrick Henry, [before 12 April 1812],” Founders Online, National Archives; Jon Kukla: Patrick Henry: Champion of Liberty(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 67.

[3]John Carlyle to George Carlyle, August 21, 1769. Printed in J. F. Carlyle, ed., The Personal and Family Correspondence of Col. John Carlyle of Alexandria, Virginia, [2011].

[4]Harry Piper to Mr. Dixon and Mr. Littledale, June 8, 1769, Harry Piper Letters 1767-69, Edith Moore Sprouse Papers, Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library.

[5]“Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions, 22 June 1770,” Founders Online, National Archives; Bruce a. Ragsdale, A Planters’ Republic: The Search for Economic Independence in Revolutionary Virginia (Madison, W.I.: Madison House, 1996), 92-95.

[6]Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason: 1725-1792 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 1: 133.

[7]William James Van Schreeven, Robert L. Scribner, and Brent Tarter, comp. and ed., Revolutionary Virginia: Road to Independence, 7 vols. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973-83), 7: 729-30.

[8]Connecticut Gazette, June 24, 1774; “Letter from Alexandria, in Virginia, to a Gentleman in Boston,” American Archives, Series 4, 1: 517-18.

[9]“Fairfax County Resolves, 18 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; Jeff Broadwater, George Mason: Forgotten Founder (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 65-67.

[10]Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, July 17, 1774, Founders Online, National Archives; Fairfax to Washington, August 5, 1774, Founders Online, National Archives.

[11]Nicholas Cresswell, The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777 (New York: L. MacVeagh The Dial Press, 1924), 43-46.

[12]Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), December 29, 1774; Van Schreeven, Scribner, and Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia, 7: 750.

[13]Rutland, The Papers of George Mason, 1: 210-11; William E. White, “The Independent Companies of Virginia, 1774-1775,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 86, no. 2 (Apr. 1978): 149-162; Michael A. McDonnell, The Politics of War: Race, Class, & Conflict in Revolutionary Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 40-46; Cresswell, Journal, 59.

[14]Van Schreeven, Scribner, and Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia, 4: 82-83; McDonnell, The Politics of War, 137.

[15]“Plan and objects of Connolly’ s Secret Expedition,”American Archives, Series 4, 4: 616; “Affidavit of William Cowley,” American Archives, Series 4, 3: 1047-48; McDonnell, The Politics of War, 130-31, 137; Rutland, The Papers of George Mason, 1: 258-59.

[16]Lund Washington to George Washington, January 17, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives; Lund Washington to George Washington, January 31, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives; “Stephen West to Maryland Council of Safety,”American Archives, Series 4, 4: 885-86.

[18]Norwich Packet, August 19, 1776; “Letter from Virginia Committee of Safety to Maryland Council of Safety,”American Archives, Series 4, 5: 141; “Virginia Council Authorize the Purchase of Cannon,” American Archives, Series 5, 2: 1127.

[19]“Letter from the Council of Safety to the Committee for Alexandria,”American Archives, Series 5, 1: 433; Dean C. Allard, “The Potomac Navy of 1776,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 84, no. 4 (Oct. 1976): 411-430; “Letter from John Dalton to Maryland Council of Safety,”American Archives, Series 5, 5: 762; Shomette, Maritime Alexandria, 38-40.

[20]Pennsylvania Journal, May 21, 1777; Ebenezer Hazard and Fred Shelley, “The Journal of Ebenezer Hazard in Virginia, 1777,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 62, no. 4 (October 1954), 402.

[21]Virginia Gazette(Purdie), May 2, 1777; Cresswell, Journal, 236-38; William Bucker McGroaty, “Loyalism in Alexandria, Virginia,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 52, no. 1 (Jan. 1944), 35-44.

[22]John Parke Custis to George Washington, August 8, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives.

[23]Rutland, The Papers of George Mason, 1: 336.

[25]Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, 1777-1780 (Richmond: Thomas W. White, 1827), 37, 46.

[26]Deposition of John Williams, The correspondence, journals, committee reports, and records of the Continental Congress (1774-1789), 3: 189, NARA M247; Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904-37), 9: 1039.

[27]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, 10: 230-31.

[28]Heads of Family at the First Census 1790, Virginia, U.S. Census Bureau; Harry Piper to Mr. Dixon and Mr. Littledale, December 5, 1775, Harry Piper Letters 1774-75, Edith Moore Sprouse Papers, Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library.

[29]Maryland Journal, October 7, 1777.

[30]Maryland Journal, May 18, 1779.

[31]S. 36230, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, NARA M804.

[32]Virginia Gazette, (Purdie), September 12, 1777

[33]Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, 1777-1780, 73.

[34]Henry Lee, Sr. to Thomas Jefferson, April 9, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives.

[35]Peter Wagener to Jefferson from, April 3, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives; Jefferson to James Hendricks, April 12, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives.

[36]Marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780-81-82, trans. George Grieve (New York, 1827), 282; Robert Mitchell to Jefferson, April 12, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives.

[37]Pennsylvania Journal, May 2, 1781.

[38]Wiliam Pitt Palmer, ed., Calendar of Virginia state papers and other Manuscripts, 11 vols. (Richmond, 1875-93), 2: 88-89; Lafayette to Jefferson, April 21, 1781, Founders Online, National Archives.

[39]Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780-81-82,303.

[40]Richard Conway to George Washington, December 31, 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2 Comments

Nice work Kieran. Alexandria as a center for smallpox inoculation is a curiosity. Many Continental officers opposed inoculation because their units were laid up for two weeks or more with mild cases. City residents must have been pretty tolerant to put up with encampments full of sick men. Hopefully the residents were treated free of charge.

Excellent Rev War history. However, the early history of the founding of Alexandria repeats the hoary old myth — discredited since 1980 — that when the public tobacco warehouses were established in the 1730’s, that “a small community called Belhaven” sprang up in the 1740’s around the warehouses. That is simply not true— there was never a community of any sort near the warehouses before 1749. The very first appearance of the name “Belhaven” is on the town street map copied by George Washington in July 1749. The town was founded and approved as “Alexandria” but almost immediately the town council called it Belhaven, by which name it persisted into the mid-1750’s. Although no documents survive to explain why the name was switched from Alexandria to Belhaven, it was almost certainly a political act of defiance by the Scottish tobacco merchants who wanted honor Scottish patriot Lord Belhaven. And they did so in the face of anti-Scottish laws passed by Parliament in the late 1740’s after the defeat of the Jacobite Highland clans at the Battle of Culloden in April 1746. (August 10, 2023)