In October 1774, in a stunning and radical move, delegates of the First Continental Congress signed a pledge for the thirteen mainland colonies not to participate in the African slave trade. Perhaps equally astounding, Americans largely complied, turning the pledge into an outright ban.

Congress’s ban and widespread compliance with it during the Revolutionary War years has been underappreciated even by historians of the American antislavery movement. It should not be. It is true that the primary motivation for the banning slave imports was not moral outrage at the slave trade itself, but instead was a means to punish Great Britain in hopes of changing its colonial tax and trade policies. Even so, given the building opposition to the slave trade in the 1770s on moral grounds, moral outrage likely played a substantial role in the adoption of the ban. Revealingly, Congress went farther than simply prohibiting the slave trade with Britain.

Congress first banned all imports of enslaved persons. Thus, neither American slave ships, British slave ships, nor those from any other country could carry captive Africans into any of the thirteen colonies. Importantly, Congress further prohibited Americans from participating in the slave trade altogether—not just with Great Britain and its Caribbean colonies, but with any country. This slave trade ban was the first nationally organized antislavery effort in American history, and one of the first in world history.

The meeting of the First Continental Congress was a reaction to the punishments Parliament imposed on Boston for the Boston Tea Party. Parliament had attempted to force a tax on tea on the Americans, and in response Boston Whigs in December 1773 had dumped a massive shipload of tea in the harbor rather than having it landed and paying the tax. In response, Parliament quickly pushed through four acts, called the Coercive (or Intolerable) Acts. The port of Boston was closed until the tea was paid for; certain powers were taken away from the Massachusetts legislature and judiciary and given to the royal governor; British officials could be tried only in England for accusations made in the colonies; and quartering troops among the people was authorized.

To the surprise of British lawmakers and officials in London, Whigs throughout the thirteen mainland colonies of North America united in their opposition to the Coercive Acts. On September 5, the Continental Congress assembled for the first time. Meeting at Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia, eventually fifty-five delegates from twelve colonies arrived and pondered what steps to take. Only delegates from Georgia were absent. Exceptionally capable Whigs from different colonies, such as Richard Henry Lee of Virginia and John Adams of Massachusetts, met for the first time, sometimes at the nearby City Tavern.

As was typical in the political discourse of the day among American Whigs, the prospect of giving in to the demands of the British government was likened to becoming enslaved. Samuel Ward, a delegate from Rhode Island, wrote to delegate John Dickinson from Pennsylvania, “We must either become slaves or fly to arms. I shall not (and hope no Americans will) hesitate one moment which to choose.” To Ward, “even death itself” was “infinitely preferable to slavery, which in one word comprehends poverty, misery, infamy and every species of ruin and destruction.”[1]

In the past, nonimportation agreements among merchants, including those in the main ports of Boston, Newport, New York, and Philadelphia, had been a promising weapon to persuade the British government to repeal offensive trading laws. Only a lack of a nationally organized effort led to its downfall. Arthur Lee advised Richard Henry Lee, his influential brother from Virginia serving as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, that cutting off all trade with Great Britain was “the only advisable and sure mode of defense” against Britain’s wrong-headed colonial policies.[2] Richard Henry Lee agreed that imposing a uniform, continental system of nonimportation that would paralyze Britain’s commerce was “the only method that Heaven has left us for the preservation of our most dear, most ancient and constitutional exemption from taxes imposed on us not by the consent of our representatives.”[3] Support for nonimportation was building, as well as for nonexportation, but this time it would be backed by a continental assembly consisting of delegates from twelve colonies of the North American mainland. Whigs believed that harming the finances of British merchants and manufacturers would lead to their agitating the British government to end the objectionable laws against the thirteen colonies. They had a fixation that economic interests would be more influential in persuading the British government than all other forces.

On September 22, “for the preservation of the liberties of America,” delegates recommended merchants to send no more orders for foreign goods.[4] On September 27, upon a motion by Richard Henry Lee, it was unanimously resolved to import no goods from Great Britain after December 1, 1774.[5] The debate on nonimportation also included nonexportation. One delegate pointed out, “The importance of the trade of the West Indies to Great Britain almost exceeds calculation.”[6] Samuel Adams added that suspending trade with the West Indies would leave planters there short of “provisions to feed their slaves.”[7] Adams knew this would in turn hurt the productivity of British Caribbean plantations. On September 30, ordering goods from Britain’s colonies of Ireland and in the Caribbean were added to the ban.[8]

Next, Congressional delegates turned to identifying the goods that would be subject to the importation ban. Northern merchants deeply entrenched in the Caribbean trade became concerned. In debates, Isaac Low, a delegate from New York, asked, “Will, can, the people bear a total interruption of the West India trade? Can they live without rum, sugar, and molasses?”[9] Delegates believed the answer was that they could, as a sacrifice to retain their rights as free men that others enjoyed in the parent country.

Virginia’s delegates brought with them several items that probably influenced delegates to do something bold about the slave trade and slave importations. Virginia delegates carried resolutions passed at the Virginia convention held in early August 1774. The second clause read, “We will neither ourselves import, nor purchase, any slave, or slaves, imported by any person, after the 1st day of November next, either from Africa, the West Indies, or any other place.”[10] George Washington also probably brought the Fairfax Resolves (or delegates read them in local Philadelphia newspapers), which urged Patriots not to import any slaves and declared “our most earnest wishes to see an entire stop forever to such a wicked, cruel and unnatural trade.”[11]

Virginia’s delegates too brought with them a then unpublished work penned by a young Thomas Jefferson, who drew up charges against King George III. Jefferson had been too ill to attend Congress, and his friends later published his work as a pamphlet without his permission. In his A Summary View of the Rights of British America, Jefferson included the following indictment:

The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in these colonies where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves we had, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa. Yet our repeated request to effect this by prohibitions and by imposing duties which might amount to a prohibition have been hithero defeated by his Majesty’s negative, thus preferring the immediate advantage of a few British corsairs to the lasting interest of the American states, and to the rights of human nature, deeply wounded by this infamous practice.[12]

Jefferson misstated the facts when he claimed that most colonists desired the abolition of slavery, especially in light of his own fellow planters in Virginia. But many, if not most, did want to end slave importations. Interestingly, Jefferson presented ending the slave trade as a prelude to prohibiting slavery itself.

With all these new ideas floating around, on October 6 the committee appointed by Congress to specify products destined for nonimportation added tea, syrup, brown unpurified sugar—and enslaved persons.[13] If any delegate strongly opposed banning the importation of captives from African or the Caribbean, there is no record of it.[14]

The Continental Association also imposed a ban, to become effective September 10, 1775, giving Parliament time to repeal the objectionable laws, on all American exports to Britain, Ireland, and the British West Indies. South Carolina delegates, including John Rutledge and Christopher Gadsden, rather than publicly oppose the prohibition on slave imports, spent their political capital insisting that rice, which was produced with slave labor, be allowed to be exported to mainland Europe, to which the delegates finally acceded.[15]

It was not surprising that the ban on slave imports was specifically included in the Continental Association. Slaves were expressly referred to in the attempt at nonimportation in 1769 to oppose the Townshend duties. Boston was the initiator of the movement for nonimportation, and it was joined by New York City and later Philadelphia before it swept into other colonies. It appears that the first reference to enslaved persons being included in nonimportation was made by George Mason in Virginia’s nonimportation resolutions signed by most members of the House of Burgesses on May 18, 1769. The fifth resolution read, “That they will not import any slaves, or purchase any (hereafter) imported until the said Acts of Parliament are repealed.”[16] After Parliament repealed all the duties except for tea, there was another attempt at nonimportation. A nonimportation association entered into by most members of the House of Burgesses on June 22, 1770, may have been authored by Richard Henry Lee. Its fourth clause stated that “we will not import or bring into the colony, or cause to be imported or brought into the colony, either by sea or land, any slaves, or make sale of any upon commission, or purchase any slave or slaves that may be imported by others after the 1st day of November next, unless the same have been twelve months upon the continent.”[17] This last formulation, with its one year exception, was weaker than the 1769 ban. Nonimportation was relatively short-lived, especially after merchants from Newport, Rhode Island, hesitated to abide by it.[18]

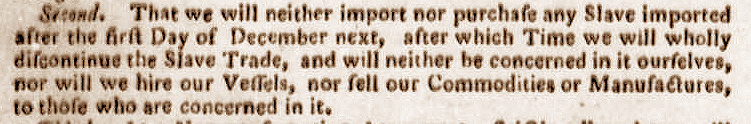

Stunningly, four years later, the Continental Association that contained the nonimportation pledge and was signed by the delegates of the twelve colonies starting on October 20, 1774, went much further than the pledge not to import African captives. The second article stated: “We will neither import nor purchase any Slave imported after the first Day of December next, after which Time, we will wholly discontinue the Slave Trade, and will neither be concerned in it ourselves, nor will we hire our Vessels, nor sell our Commodities or Manufactures to those who are concerned in it.”[19]

This was indeed momentous—the end to all participation by American merchants in the slave trade. While much of the Continental Association is based on the approach taken in the August resolves passed by the Virginia convention in early August 1774, and those resolves included a strong stand against importing any slaves from any source, they did not even hint at an outright end to participation in the slave trade.

The slave trade clause went much further than prior efforts at nonimportation. Slave traders from the thirteen colonies could not, without violating the Association, buy slaves in Africa and sell them anywhere, not just in their own colonies. Indeed, by the terms of the last part of the clause, they could not even trade with slave merchants in transactions having nothing to do with enslaved persons. The fact that the ban was contained in the second paragraph of the Continental Association reveals how strongly Congress felt about the matter.

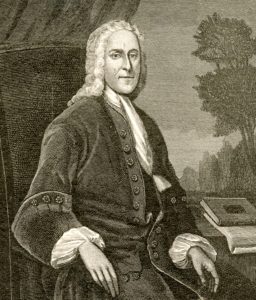

Henry Laurens, a prominent Patriot and notorious slave trader from Charleston, succinctly summarized the economic argument for ending slave imports from Britain. He wrote, “Men-of-war, forts, castles, governors, companies and committees are employed [in Africa] and authorized by . . . Parliament to protect, regulate, and extend the slave trade . . . Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, etc., live upon the slave trade.”[20] But Congress had gone much further, banning any American participation in the slave trade by itself or with any country, including France, Spain, and Portugal.

Who was behind the insertion of the broad slave trade clause in the final Continental Association agreement is not known. Members of the committee assigned to draft the nonimportation provisions were Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, Thomas Cushing of Massachusetts, Isaac Low of New York, Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania, and Thomas Johnson of Maryland.[21] Richard Henry Lee, who had given a speech against the evils of the slave trade as early as 1759, likely played an important role in the insertion of the broad slave trade clause.

No doubt Lee found a sympathetic ear in Cushing, who was part of many efforts in Massachusetts to ban importation of enslaved Africans into his colony. Samuel Adams, another influential delegate who had a history of pressing for antislavery legislation in Massachusetts, could have pushed for his friend Cushing to press for the broad ban. And in this environment swirled the recent polemics against the slave trade in Jefferson’s recent writings and in the Fairfax Resolves brought by George Washington. Crucially, none of the committee members hailed from South Carolina or Georgia, the only two colonies where slave importations had been substantial in prior years. More likely, all of these forces combined at the right time to lead to the insertion of the slave trade clause.

Whether the ban on all slave importations and all participation in the slave trade was based on the desire to harm Britain economically, on moral grounds, or both is not clear. It was probably both. The slave importation and slave trade bans are often described as primarily motivated by the desire to harm Britain economically rather than a recognition of the evils of slavery. Yet such a view ignores the fact that at the time the Continental Association was adopted, opposition to the slave trade on moral grounds was at a high point. Revealingly, Congress went further than mere nonimportation, prohibiting any participation by North American merchants and sea captains in the slave trade. This by itself indicates that moral and humanitarian opposition to the slave trade must have been a persuasive factor. If the committee had just wanted to increase the values of enslaved people currently held in their colonies and to protect against the risk of slave insurrections, they could have simply banned slave imports.

Based on the makeup of the committee that drafted the Continental Association, it appears that moral and humanitarian grounds did play an important role. Only two southerners were on the committee, and one of them was the influential Richard Henry Lee, who, despite being a slave owner, held ideological antislavery feelings. Thomas Johnson of Maryland was on the committee too. A substantial slaveholder as well, he came from a state that wanted to ban imports of enslaved persons.

Why did Congress decide to ban all slave importations and participation in the slave trade? After all, merchants in Charleston and Savannah could have worked with French, Spanish, or Portuguese slave traders, and the wartime disruption of commerce with Britain did force states to develop direct trade with European powers. There were likely a number of factors at play. First, in the North there was rising opposition to the slave trade on moral grounds. Second, mostly out of economic interest, and on moral grounds at least with a few leaders such as Thomas Jefferson and George Mason, Virginia and Maryland had long tried to limit slave importations. Third, at this time, the power of the slave interests in South Carolina and Georgia was at a nadir. Slave merchants and planters who opposed nonimportation had tried to stack the delegates the colony sent to Philadelphia with their allies, but instead, a general meeting of Patriots voted in delegates with full authority to agree to nonimportation.[22] Georgia was not even represented in the Congress.

It is possible that committee members considered that an outright ban on all slave importations would be easier to enforce than a partial ban directed solely at Great Britain. They may have thought that Patriot local committees would face difficulties trying to identify what slave had been purchased from Africa by an English trader and what slave had not. At this time, British merchants in Liverpool, Bristol, and London dominated the Atlantic slave trade. If imports from, say, Spain were permitted, it might be easy for a Spanish merchant to purchase a captive taken from the African coast by a Bristol merchant and resold to the Spanish merchant in Cuba, and then sell the enslaved person to a Charleston merchant. Accordingly, ease of enforcement may have been an important factor in banning all slave importations.

Even more interesting is the question of why Congress banned all participation in the slave trade by American merchants. After all, a Newport merchant could purchase slaves on the Gold Coast of Africa directly from a local chieftain and resell them to a Spanish or French buyer without importing the slave into any of the thirteen colonies or having any involvement with British factors or merchants. While it is true that at this time North American slave merchants had not yet developed business relationships with Spanish or French buyers, they could have tried to do so. Here, moral objections to the slave trade may have been paramount. Still, delegates might have been concerned that it would have been easy for North American slave merchants to disguise their purchases from British factories (holding pens for enslaved persons) and forts on the African coast. Again, ease of enforcement may have been a key factor in banning all participation in the slave trade by mainland colonial merchants. In addition, slave merchants did not then have much power in the Continental Congress. The colony with the most slave traders, Rhode Island, was represented in Congress by Samuel Ward and Stephen Hopkins, who supported the slave trade prohibition.

Surprisingly, the broad slave trade ban resulted in little comment outside of Philadelphia. Patriots had other matters to attend to in the growing crisis. The Danbury, Connecticut, town meeting in December 1774 was an exception. It noted “with singular pleasure . . . the second Article of Association, in which it is agreed to import no more Negro Slaves.” Calling slavery “one of the crying sins of our land,” the town meeting gave as its rationale that it was “palpably absurd to loudly complain of attempts to enslave us, while we are actually enslaving others.”[23]

Two Philadelphia merchants must not have been aware of the deep involvement in the slave trade by one of the Newport merchants they dealt with, Christopher Champlin. In an October 25, 1774 letter, they informed Champlin of the various nonimportation and nonexportation resolutions just passed by Congress, adding, “the slave trade to be discontinued after the first of December . . . which is a most excellent resolve.”[24]

The Continental Association contained terms for its own enforcement. Delegates knew that Congress had no power to enforce the association. It was recommended that in every county, city, and town a committee be chosen to “observe the conduct of all persons touching this association,” publish in local newspapers all violations, and “break all dealings” with any person who violated the association. Delegates were aware that every colony and many localities had formed extralegal committees of correspondence in 1773. Members of committees of correspondence were encouraged even to look at custom house records to seek out violators. Delegates also promised not to trade with “any colony or province, in North America,” that would not accede to or did “hereafter violate this Association.”[25]

A few days before it adjourned, Congress voted on October 22 to hold another Congress at Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, unless Parliament resolved their grievances in the colonies’ favor. Among the first Congress’s achievements, the Continental Association stands out as an important development that ultimately led to war between the thirteen colonies (not just Massachusetts) against Great Britain, and eventually to all of the colonies declaring their independence. But only a few envisioned that development in October 1774. John Dickinson, a Pennsylvania delegate, wrote to Arthur Lee that “the colonists have now taken such ground that Great Britain must relax [her laws against the colonies], or inevitably involve herself in a civil war.”[26]

The delegates at the First Continental Congress, expecting the British government would respond to economic pressure from their boycott, were overly optimistic. British merchants and West Indian planters did petition Parliament to press for compromise, pointing out the drastic economic impact the boycott or war would have on their fortunes. But the appeal failed to consider other factors taken into account by British government decision makers, such as the emotions of pride and stubbornness, parochial attitudes towards colonists, and concern that compromising too much would jeopardize the growing British empire. Parliament refused to budge.

Enforcement of the Continental Association passed to local Patriot committees. Even the slave-holding colonies of Virginia and South Carolina enforced the ban on importation of African captives. Patriotism trumped the desire to continue to allow slave importations—at least in the short term.

Two early enforcement actions set precedents. On March 6, 1775, the Committee of Correspondence of Norfolk, Virginia, determined that John Brown, a Norfolk merchant, had conspired to import slaves into Virginia and therefore had “willfully and perversely violated the Continental Association.” Pursuant to the eleventh paragraph of the Continental Association, the Committee ordered that the transgression be publicized, that Brown be identified as one of “the enemies of American Liberty, and that every person may henceforth break off all dealings with him.”[27]

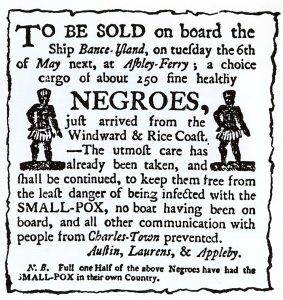

The March 6, 1775 edition of the South Carolina Gazette announced that the ship Katherine, out of Bristol, England, had arrived in Charleston harbor, sailing from the West Coast of Africa from Angola, with 300 enslaved persons on board, consigned to Charleston slave trader John Neufville. Readers must have wondered if the human cargo would be permitted to land in Charleston, since the Bristol captain had not had any notice of the nonimportation ban when he purchased the captives in Angola. In a follow-up, the March 27 edition of the same newspaper informed readers that the 300 African captives “according to the Continental Association could not be imported or purchased here,” with the result that the vessel “sailed for the West Indies with her whole cargo.”

What about Rhode Island, the leading slave trading colony in North America? After all, it had beaten back an attempt to prohibit entirely the colony’s participation in the slave trade in June 1774. Samuel Ward and Stephen Hopkins, Rhode Island’s two delegates to the Continental Congress, both signed the Continental Association. Shortly after returning to their respective homes in Rhode Island, they travelled to Providence in early December to report to the General Assembly on the developments in Philadelphia. After listening to the presentation, the General Assembly voted to adopt the Continental Association.[28] The colony’s small number of slave merchants were overwhelmed by the patriotic surge to support the struggle of Boston’s Whigs against British oppression. In this charged atmosphere, Rhode Islanders hardly considered rejecting the Whig cause just to keep the slave trade open.

In mid-December, the respected and well-liked Samuel Ward of Westerly, in a letter to fellow-delegate John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, exulted that Rhode Islanders were “universally satisfied with the proceedings of Congress, and determined to adhere to the Association.” Ward added, as if in disbelief, “Even the merchants who suffer the most by discontinuing the slave trade assure me they will most punctually conform to that Resolve and the country in general is vastly pleased with it.”[29] Ward, a former three-time governor of Rhode Island whose support came mostly from Newport, was well positioned to know whether or not the colony’s slave traders were willing to abide by the ban. Rhode Island’s other delegate who signed the Continental Association, Stephen Hopkins, had recently pressed for the Rhode Island General Assembly to end slave importations; Newport slavers could not count on him for support. The General Assembly, satisfied with work of both Ward and Hopkins, appointed them to serve as delegates to the Second Continental Congress.[30]

Whether Newport slavers would really abide by the ban, given the well-deserved reputation of all Rhode Island merchants for evading British trade laws, remained an open question. An initial indication that Newport merchants would abide by the ban was the scramble to send out ships to Africa before the ban took effect on December 1, 1774. In the first ten months of 1774, thirteen slave ships cleared out of Newport for Africa and two sailed from nearby Bristol, Rhode Island. In the single month of November, after learning of the ban shortly to take effect, five ships sailed out of Newport, and one out of Bristol, bound for Africa, with three of them departing with just two days to spare. Several Newport slaving vessels that could not be made ready to sail by December 1 were reportedly kept in port.[31]

Two prominent Newport slave merchants, Christopher and George Champlin, informed their English joint venturer that their brother, Robert Champlin, had sailed their sloop out of Newport bound for Africa nine days prior to the December 1 deadline. But they also warned their London partners, “By the resolves of the Continental Congress, all trade is stopped from this continent to Africa [starting] 1st December last, since which no vessel has sailed for thence, nor will any till our troubles are settled.”[32]

The Association’s ban on American participation in the slave trade was surprisingly successful. Jay Coughtry, who has studied the slave voyages of Rhode Island merchants most closely, reported no slave voyages departing from a Rhode Island port after December 1, 1774 and before 1784.[33] He further observed that impact of the American Revolution on the Atlantic slave trade exceeded that of the impact of prior wars between Great Britain and France: “the American Revolution finally accomplished what three colonial wars had been unable to do; and from 1776 to 1783, the Rhode Island slave trade ceased.”[34] A search of an incredibly detailed online resource, which attempts to record every trans-Atlantic slave trading voyage that ever occurred, reveals no clear evidence of a slave ship owned by an American merchant departing from a North American port for Africa after December 1, 1774 and before 1783, when the Revolutionary War ended.[35] My own investigation reveals that while almost all American slave merchants abided by the slave trade ban, not all slave ship captains did. But that is another story.

On April 6, 1776, the Continental Congress stepped back from its total ban prohibiting Americans from participating in the slave trade. The main thrust of the resolution was a momentous one—to permit American merchants to export goods and merchandise to any foreign country, and to import goods and merchandise from any foreign country “not subject to the King of Great Britain.”[36] The resolution added that “no slave be imported into any of the thirteen United Colonies” (they were not states yet). No mention was made of the ability of Americans to participate in the slave trade with other countries. A fair reading of the two resolutions is that American merchants could not deal in enslaved persons with Britain or any of its colonies, but could purchase captives in Africa from non-British interests and sell them to French, Spanish, or Portuguese slave buyers in the New World. They still could not, however, import any African captives into North America.

Congress’s total ban on Americans participating in the slave trade was short-lived. With South Carolina and Georgia paying more attention in the Second Continental Congress, the ban was difficult to continue. The need for unanimity in the face of a difficult war against Britain was paramount. But for a short time, Congress did have in place a total ban that a decade earlier no one thought was possible. And its prohibition on imports of African captives lasted throughout the war. These were steps, albeit relatively small ones, towards the formal end of the African slave trade and abolition of slavery in the North. Of course, stopping violations of the slave trade ban and ending slavery in the South were more intractable problems that would take longer to resolve.

[1]S. Ward to J. Dickinson, December 14, 1774, in Paul H. Smith, ed., Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1976), 269.

[2]A. Lee to R. H. Lee, March 18, 1774, in in Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 4th Ser., vol. 1 (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clark, 1853), 229.

[3]R. H. Lee to A. Lee, June 26, 1774, in James Curtis Ballagh, ed., The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1911-14), 1: 117.

[4]Resolution, September 22, 1774, in Worthington C. Ford, ed., The Journals of the Continental Congress, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1905-37),1: 41.

[5]Resolution, September 27, 1774, in ibid., 43; Oliver Perry Chitwood, Richard Henry Lee: Statesman of the Revolution (Morgantown, WV: West Virginia Library, 1967), 68.

[6]John Adams’ Notes of Debates, September 26-27?, 1774, in Smith, Letters of Delegates 1: 103.

[7]Samuel Adams’ Notes on Trade, September 27?, 1774, in ibid., 108.

[8]Resolution, September 30, 1774, in ibid, 51-52.

[9]John Adams’ Notes on Debates, October 6, 1774, in Smith, Letters of Delegates 1: 152.

[10]Virginia Convention Resolutions, August 8, 1774, in Julian Boyd, ed., Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950), 138.

[11]Fairfax Resolves, July 18, 1774, in W. W. Abbott and Dorothy Twohig, eds., Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 10 (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1995), 125.

[12]Jefferson, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America . . . , 1774, in Gordon Wood, ed., The American Revolution, Writings from the Pamphlet Debate, 1764-1776, 2 vols. (New York, NY: Library of America, 2015), 2: 101-02.

[13]Continental Association, October 20, 1774, in Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress 1: 77; David Ammerman, In the Common Cause. American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774 (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1974), 81.

[14]See Ammerman, In the Common Cause, 81-87.

[15]Samuel Ward Diary Entry, October 20, 1774, in Smith, Letters of Delegates 1: 221 and n1, 222; Chitwood, Richard Henry Lee, 68-69.

[16]Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions, May 18, 1769, in Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason, 1725-1792, vol. 1 (Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina University Press, 1970), 1: 110; see also Draft of Nonimportation Association, April 23, 1769, in ibid., that George Mason shared with George Washington.

[17]Virginia Nonimportation Association, June 22, 1770, in ibid., 1: 122; for Richard Henry Lee’s authorship, see also ibid., 120, note and 125, note.

[18]See Elaine Forman Crane, A Dependent People, Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era (New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 1985),117-18.

[19]Continental Association, October 20, 1774, in Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress 1: 77.

[20]H. Laurens to J. Laurens, August 14, 1776, in David R. Chesnutt, et al., eds., The Papers of Henry Laurens, vol. 11 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1989), 11: 224.

[21]Resolution, September 28, 1774, in Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress 1: 53.

[22]See Elizabeth Donnan, rf., Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution, 1930-35), 4: 470n1.

[23]Resolution, December 12, 1774, in Force, American Archives, 4th Ser., 1: 1038-39.

[24]Stocker & Wharton to C. Champlin, October 25, 1774, in “Commerce of Rhode Island,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 7th Ser., 10: 517 (1914).

[25]Continental Association, October 20, 1774, in Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress 1: 79.

[26]J. Dickinson to A. Lee, October 27, 1774, in Smith, Letters of Delegates, 1: 250.

[27]Proceedings of the Committee of Correspondence, March 6, 1775, in Force, American Archives, 4th Ser., 2: 33-34.

[28]See John R. Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. 7 (Providence, RI: A. C. Greene, 1862), 263; Providence Gazette, December 3, 1774.

[29]S. Ward to J. Dickinson, December 14, 1774, in Smith, Letters of Delegates, 1: 269.

[30]Bartlett (ed.), Records of the Colony of R.I., 7: 264-65.

[31]Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/search (search voyages beginning in 1774).

[32]C. and G. Champlin to Threlfal and Anderson, January 17, 1775, in Donnan, Documents of the Slave Trade, 3: 301.

[33]Rhode Island Slave Trading Voyages, 1709-1807, in Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807(Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1981), 260.

[34]Coughtry, Notorious Triangle, 31.

[35]Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/search (search voyages from 1774 to 1783).

[36]Resolution, April 6, 1776, in Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress 4: 257-58.

5 Comments

Chris, an excellent piece of research and writing.

Outstanding and perceptive 3 articles on the slave trade. Unfortunate it has not generated a larger reader response.

These three excellent articles should be essential reading for those of us hoping to counter the terrible current ahistorical bias. Despite considerable reading on the era, I had come to assume that only the faintest glimmers of abolitionist sentiment existed before the war. Christian McBurney is to be praised and thanked for setting me and all of us straight.

Thank you Ken, John and Jon! I appreciate your comments. Best, Christian

Three great articles. I have read about slavery during my colonial research. One item I found was the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition against slavery. The movement started early in soon to be America.