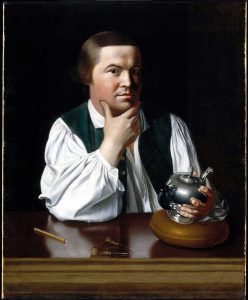

It may have been Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s patriotic paean that belatedly canonized a heroic horseman as a key figure of the American Revolution, but it was John Singleton Copley who provided posterity with the definitive visual representation of the famous midnight rider. Seven years before Paul Revere spread the alarm through every Middlesex village and farm—and nearly a century before Longfellow made the deed immortal—Copley painted Revere’s portrait. In Copley’s picture, Revere, then known primarily as a successful silversmith and engraver, palms a shiny silver teapot in his meaty left hand. His engraving tools lie scattered on the polished wooden table, on which rests his right elbow, concealed by the billowing cascades of his white shirtsleeve. He gently presses his right thumb and forefinger against his chin—a pensive pose, perhaps one that Copley made him hold for hours on end. Revere’s eyebrows are raised; he stares directly out at the viewer.

Copley’s prodigious painterly talent is on full display here, in a portrait renowned both for its artistic merit and for the eventual celebrity of the sitter, but this represents just one of Copley’s many remarkable renderings of the era’s distinguished Bostonians. Samuel Adams, John Hancock, William Brattle: everyone who was anyone, Patriot and Tory alike, sat for Copley. But even with such notable clientele, Copley desired more than Boston could offer. In 1774, just six years after he completed the revered Revere portrait, he set off for London, hoping to ply his trade in a more sophisticated art market before making his way to the Continent on his own Grand Tour.

Copley’s stay in Europe ended up becoming a permanent one—he died in London in 1815, never returning to America after his departure—but in 1774 he did not know that his transatlantic trip would turn into anything more than a temporary sojourn. Upon arriving in London, he wrote a letter to his wife Susanna, who remained in Boston while her husband made his rounds on the European circuit. In this correspondence with Susanna, he expressed his initial thoughts on English life and explained how he had been spending his first weeks there.

Copley addressed the letter, dated July 11, 1774, to “my ever Dear Sukey,” his affectionate nickname for his wife. He wasted little time before attempting to win some good husband points, mentioning how happy he was to “gratify myself in one of the first & greatest pleasures I shall find while absent from you, that of writing to you.”[1]Then, after this prefatory sweet-talk, Copley spent the majority of the letter giving his exceedingly positive first impressions of England. Since he had just arrived in London, he explained that “I have not yet seen anything scarcely of this Superb City, tho What I have seen only convinces me I was not mistaken in my Ideas of its grandeur.”[2] With this sentence, Copley admitted that he was predisposed to like London from the outset. Most obviously, he called it a “Superb City” even though he had “not yet seen anything scarcely of” it. Moreover, the words “my Ideas of” are in superscript, meaning that Copley included them as post hocadditions to a sentence that originally read “I was not mistaken in its grandeur.” In essence, Copley at first intended to confirm to his wife the grandeur of London—sight mostly unseen—but then, upon deciding that he needed to temper his language a bit, opted only to confirm to his wife his Ideas of the grandeur of London.

Next, Copley turned toward a direct comparative analysis of England and America. Referencing a prior conversation that he and his wife must have had with a friend, he claimed that “Mr. ––G was greatly mistaken when he said that we were Saints & Angels in America compared to those that inhabit this Country.”[3] On the contrary, thought Copley, the English acted much more kindly toward one another than the Americans did, a conclusion he drew based not on any interactions with actual Englishmen but rather on his travels through the English countryside on the way into London. Unlike in America, where “even good forces will not secure the property of the Farmer from being trespassed on in the most shamefull manner,” Copley noted that “in this 72 Miles of the most publick Road in England through which I passed you will see miles together of Grain, Beans, Grass, &c without any fence or hedge & through which a neat smooth Road is cut of no great width—only just sufficient for two Carriags to pass & yet not a spore of Grass, Grain, or Beans, trampled no more than if such a trespass would be instant Distruction to the offender.”[4] The English, in other words, simply showed more respect for private property than the Americans did—a somewhat ironic observation, considering the revolutionary foment running high in 1774 among liberty-loving Americans against their supposedly despotic British overlords. To hammer the point home, Copley added that “we Americans seem not halfway remove’d from a state of nature when brought into comparison with those of this Country.”[5] Intentional or not, the Hobbesian overtones of America’s “state of nature” leaves little doubt as to which side of the Atlantic Copley thought was functioning better.

Not only did Copley’s ride into London illuminate English customs and civility, but it was also cheap. Copley remarked that he did not “find in the Country the traviling so dear [i.e., expensive] as I see thought [sic] it was[;] you will be your own Judge in of this matter when I inform you my whole expense in coming 72 Miles amounted to 3 Guineas.”[6] And this affordability did not come with any corresponding dip in quality, for the ride was “as good in all things & and Genteel as any Gentleman would wish and my Carriage as Genteel as any Charriots that are in Boston.”[7] Better still, the ride afforded the opportunity for a sightseeing experience that could not be matched in America: “at Canterbury I was entertained with a sight of the Gothick Cathedral built by 4 Saxson Kings[;] this is a very curious Building and contains several Monuments no less so.”[8]

At this point in the letter, though, Copley needed to cut short his glowing assessment of his first English carriage ride, for he had important business to attend to. “Governor Hutchinson,” he wrote, “is to be here at 1 oClock when I shall have the pleasure of seeing him as he is now coming I must break off.”[9] The Governor Hutchinson to which Copley referred was none other than Thomas Hutchinson, the recently exiled governor of Massachusetts who had arrived in England at around the same time as Copley. But Copley did not just “break off” abruptly; instead, he ended his letter with the same brand of spousal flattery he had deployed in his opening. Signing off, he professed, “I am[,] my ever dear Sukey with an affection not to be lessned by the distance I may be at or the amusements of I may meet with[,] Your sincere & Loving Husband John Singleton Copley.”[10]

On the surface, this letter serves as an interesting window into the mind of a notable American abroad. Copley, though physically separated from his wife, was clearly careful to remain in her good graces, as evidenced by the tender sentiments he used to open and close the letter. He certainly enjoyed his first few days in England, which, judging by his references to his preconceived notions of “its Grandeur,” it seems he was already inclined to enjoy anyway. He even used his first carriage ride to favorably compare English mores with those of America. And, based on the eminent Loyalist authority he was expecting to see later that day, he was unafraid to be caught interacting with a man who was reviled by the Patriots in his hometown.

But with a little more context, this letter becomes even more worthy of analysis. Copley’s family history can help account for why he might have included such a favorable depiction of English life from the get-go, and his meeting with Hutchinson might explain why he took care to include such affectionate words for his wife. Susanna Copley (née Clarke) was the daughter of Richard Clarke, one of the leading importers in Boston.[11] When John Singleton Copley married Susanna in 1769, he was marrying directly into the family and fortune of Richard Clarke & Sons, which Ann Uhry Abrams explains was one of the “three Massachusetts firms . . . designated as consignees for the British East India Company.”[12] And the other two high-flying firms had Clarke connections as well: Susanna’s cousin Joshua Winslow operated one, and Governor Hutchinson’s sons Thomas and Elisha—who also happened to be Susanna’s cousins, making Copley a distant relative of the governor—ran the other.[13]

Copley’s marriage into the Clarke family did more than just guarantee his financial security and allow him to relocate to the chic Beacon Hill neighborhood: it made him a part of a family sympathetic to, and with a tangible monetary and political stake in, big Boston business and the British interests that it represented. Copley himself tried to practice a clear policy of neutrality[14]—his primary concern was painting, and by remaining apolitical he avoided offending a potential client’s sensibilities and therefore losing out on a commission—but against the backdrop of the 1773 tea crisis, it became all but impossible for Copley to continue skirting the political issues. Patriot demonstrators frequented the house of Susanna’s father, threatening mob violence. When the Dartmouth dropped anchor in Boston Harbor, Copley himself acted on his father-in-law’s behalf by addressing a crowd of angry Bostonians and trying to defuse the situation with a middle-ground offer. Copley proposed that, rather than sending the tea back to England as the Patriots hoped, the consignees could safely store it until a more permanent compromise could be reached.[15] The furious Patriots dismissed Copley’s suggestion out of hand, and the Boston Tea Party took place weeks later—and the rest, of course, is history. From then on, Boston became less safe for its preeminent painter: Abrams mentions an incident in April 1774, when “a group of demonstrators caused a disturbance at [Copley’s] residence, acting on suspicion that he was housing a British official.”[16] In June of that year, Copley boarded a ship bound for England. Getting out of town was not his sole motivation, as he had long wanted to travel to Europe, but the demonstrators’ disturbance may have been an added incentive.

Under this light, Copley’s remarks to Susanna about English respect for private property gain an additional layer of significance. The man who mentioned that in America “even good forces will not secure the property of the Farmer from being trespassed on in the most shamefull manner” was, in fact, a man whose property had recently been trespassed on by Americans in the most shameful manner, and he was writing to a woman whose father had experienced these shameful trespasses with some regularity. Copley was not writing as a detached observer; he was contrasting the unfair treatment of himself, his wife and his wife’s family in America with the omnipresent aura of civility in the England. The American “state of nature” was not a mere abstract concept but rather a reality that had materialized on his very own doorstep.

And almost nobody had borne the costs of this American “state of nature” more than the man that Copley was preparing to greet as he finished up his letter to Susanna: Governor Hutchinson, Copley’s relative by marriage and Massachusettsans’ favorite target of odium. It is unclear exactly what Hutchinson discussed with Copley in this particular July 11 meeting, but a letter that Copley wrote to his wife the following month provides a possible answer.

In this August 17 letter, Copley told his wife that he might have the opportunity to paint a portrait of the King and Queen—the crown jewel of all commissions and, in Copley’s words, “boath an Honour and an Introduction that seldom falls to the share of great artists.”[17] How did Copley, a fresh arrival from the Colonies, find himself in contention to paint such a prestigious picture? In his words, it was because “Gov Hutchinson has asked Lord Dartmouth to request it of the King as a favour.”[18] It is not improbable, then, that this potential commission was a topic of conversation between Copley and Hutchinson on July 11, either because Hutchinson brought up the possibility or because Copley himself expressed his desire. Even if Copley did not have the King and Queen specifically in mind, he may well have asked if Hutchinson could find him some distinguished clientele.

If Copley knew going into his July 11 meeting with Hutchinson that he wanted to request such a favor from the former governor, it would help account for Copley’s effusively tender words to his wife in the letter (beyond the obvious explanation that Copley simply loved and missed Susanna). Judging by his later letter, Copley had a hunch that Susanna would not take particularly kindly to the prospect of spending even more time apart from her husband while she waited for him to paint a royal portrait. On August 17, he leaned upon logic that was tenuous at best and nonexistent at worst in saying that he did not think that “this delay [to paint the royal portrait] will at all lengthen our seperation on the contrary I think it will shorten it.”[19] This line seems to have been a ploy on Copley’s part to preempt his wife from pleading with him to reject the commission in the interest of expediting his return home, as earlier in the letter he had already acknowledged “the anxiety you feel for the separation from me.”[20] Clearly, Copley thought that the honor alone of painting a royal portrait would not be enough for Susanna, so he had to (at least nominally) affirm that it would not lengthen his absence from his family.

If Copley already knew on July 11 that he would be actively seeking these potentially trip-extending commissions, then his endearing words for his wife on that date could have been an early attempt to butter her up. He had missed her from the outset, he could always argue, and she could reread his July 11 correspondence for confirmation! After all, he wasted precious little time upon arriving in London before he decided to “gratify myself in one of the first & greatest pleasures I shall find while absent from you, that of writing to you”—even if the very next thing he did was to ask Hutchinson about a royal commission that would keep him absent for even longer.

In the end, Copley wound up losing out on the commission before departing for his tour of Continental Europe, but the very fact that he was in contention to win it adds a bit of a wrinkle to that famous picture of Paul Revere. A year before the midnight ride and the shot heard ’round the world, the man who had so brilliantly executed the iconic image of the eventual midnight rider was in London, speaking with Thomas Hutchinson about the prospect of painting the monarchs of an empire that would soon be at war with the silversmith in shirtsleeves and his countrymen.

[1]John Singleton Copley to Susanna Copley, July 11, 1774, Brandeis University Library, omeka.lts.brandeis.edu/items/show/2.

[11]Ann Uhry Abrams, “Politics, Prints, and John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark,” The Arts Bulletin 61, no. 2 (1979): 267, doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1979.10787661.

[17]John Singleton Copley to Susanna Copley, August 17, 1774, Brandeis University Library, omeka.lts.brandeis.edu/files/original/fe1a3bcefc3330ee51b749a13d85552c.pdf.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...