It was the one of the worst defeats suffered by the Americans during the War for Independence, certainly the worst over which George Washington had direct command. Historian David McCullough perhaps characterized the debacle best, writing that after experiencing “one humiliating, costly reverse after another,” during the New York campaign of 1776, “the surrender of Fort Washington on Saturday, November 16, was the most devastating blow of all, an utter catastrophe.” And blame for this catastrophe, with out a doubt, ultimately rested with the American commander-in-chief.[1]

Why Washington made such a drastic error has been the subject of debate and conjecture almost since the moment of Fort Washington’s capitulation. Joseph Reed, a colonel and the Continental army’s adjutant general at the time, vented his frustration and disillusionment with Washington in a letter to Maj. Gen. Charles Lee shortly after the fort fell. “Oh! General,” Reed wrote Lee, “an indecisive mind is one of the greatest misfortunes that can befall and army: how often have I lamented it this campaign.” Lee, for his part, chastised Washington directly: “Oh General, why would you be over-perswaded by Men of inferior judgement to your own?” And privately, referring to the surrender as “the ingenious maneuver of Fort Washington,” Lee expressed his disgust to his peer, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. “There never was so damned a stroke. Entre Nous, a certain great man is damnably deficient”[2]

On a certain level, Lee had a point. Fort Washington, although seemingly formidable, was hardly impregnable. In fact, it was barely habitable. Alexander Graydon, a captain in the 3rd Pennsylvania Battalion who was captured after the fort fell, notes in his memoirs that the site had “no barracks, or casemates, or fuel, or water within the body of the place.” And although positioned at a strategic point on cliffs about 200 feet high overlooking the Hudson River, it was essentially “an open, earthen construction” intended, along with its counterpart, Fort Constitution (later Fort Lee) to anchor a series of obstructions whose purpose was to deny the British navy free navigation of the river. That purpose failed on November 7, 1776, when three British ships passed beyond the obstructions, proving their “inefficacy.” Graydon’s conclusion about Fort Washington summed the situation in a dismal light. There was nothing “so far as I can judge,” he wrote, that “could entitle it to the name of a fortress, in any degree capable of sustaining a siege.”[3]

Historians have proven somewhat more sympathetic than the irascible Charles Lee, or the bitter Alexander Graydon, chalking the poor decision up to a mind clouded by fatigue. Edward Lengel wrote of Fort Washington, “an engineer would have seen the futility of trying to hold such a place against the combined might of the British army and navy, but Washington was no engineer.” Ron Chernow “suspects that, in losing New York City, his [Washington] self-confidence had suffered serious damage and that he had temporarily lost the internal fortitude to obey his instincts.” And David McCullough noted, “like most of the army he led, Washington was still exhausted and dispirited. To some who were closest at hand he seemed a little bewildered and unsuitably indecisive.”[4]

For his part, Washington’s own explanations for the disaster evolved as the war progressed. As historian Benjamin Huggins has illustrated, the commander-in-chief was far more defensive about his role in the loss in the immediate aftermath of the surrender, effectively passing the buck on to Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene.[5] “I wrote to Genl Greene, who had the Command on the Jersey Shore,” Washington reported to John Hancock, President of Congress, “directing him to govern himself by Circumstances, and to retain or evacuate the post as he should think best.”[6] And true enough, Washington’s letter to Greene on November 8 did authorize the latter to “give such Orders as to evacuating Mount Washington as you judge best.”[7] But Washington arrived at Greene’s headquarters at Fort Lee, New Jersey, three days prior to the British attack, with plenty of time to have overruled Greene. Three years later, in August 1779, a more experienced, more confident Washington admitted his own indecision to Joseph Reed:

When I came to Fort Lee & found no measures taken for an evacuation in consequence of the order aforementioned. When I found General Greene of whose judgment & candour I entertained a good opinion, decidedly opposed to it—When I found other opinions coinciding with his—When the wishes of Congress to obstruct the Navigation of the North river, and which were delivered in such forceable terms to me, recurred—When I knew that the easy communication between the different parts of the army then seperated by the River depended upon it—and lastly, when I considered that our policy led us to waste the campaign without coming to a general action on the one hand, or to suffer the enemy to overrun the Country on the other, I conceived that every impediment which stood in their way was a mean to answer these purposes, and when thrown into the scale of those opinions which were opposed to an evacuation caused that warfare in my mind and hesitation which ended in the loss of the garrison, and being repugnant to my own judgment of the advisability of attempting to hold the Post, filled me with the greater regret.”[8]

Yet what Washington missed in the outline of considerations he listed above, and what his critics, modern and contemporary, also overlook is the possibility that on some level George Washington really did believe Fort Washington was defendable. The reason he was so easily persuaded to make a stand was because holding the ground, in this mind, was plausible. Call it the Bunker Hill Effect.

Although the nascent American army lost the ground at the Battle of Bunker Hill, they thoroughly bloodied the redcoats, who, at great cost, had to launch three successive frontal attacks against the patriot entrenchments on Breed’s Hill. The carnage shocked the British. “A dear bought victory,” wrote Maj. Gen. Henry Clinton who watched from Boston, “another such would have ruined us.” Maj. Gen. William Howe, who at the time was second-in-command to Gen. Thomas Gage, and led the assault personally, admitted that the ferocity of the patriot resistance on Breed’s Hill was “a Moment that I never felt before.” By the end of the day, his entire staff was either dead or wounded. One of Gage’s subordinate officers reported back to a friend in England, “Such ill conduct at the first outset argues a gross ignorance of the most common and obvious rules of the profession and gives us for the future anxious forebodings.”[9]

Initially the Americans viewed the retreat from Breed’s and Bunker hills as a failure. This changed over time. Indeed, Washington would invoke the memory of the action at Breed’s Hill in his general orders, August 13, 1776, urging his men to “remember how they [the British] have been repulsed . . . by a few brave Americans.”[10] And as they prepared to receive the enemy at Long Island, the commander-in-chief again on August 23 reminded his troops how the British regulars “found by dear experience at Boston, Charleston [Breed’s Hill], and other places, what a few brave men contending in their own land, and in the best causes can do against base hirelings and mercenaries.”[11] In a letter to John Hancock on September 8, Washington outlined his strategic plans based upon the strengths of his army (such as it was) and influenced by the example above. He argued that “on our side the War should be defensive, It has been even called a War of posts.” And to that end, Washington determined to establish “Strong posts at Mount Washington on the upper part of this Island and on the Jersey side opposite to It.”[12]

So, in 1776, at least, Washington’s strategic philosophy was that the American army could repel the British “if opposed with firmness, and coolness” and “with our advantage of Works and Knowledge of the Ground.” Even after losing the Battle of Brooklyn, barely extricating the army from Long Island, then abandoning the city of New York entirely, Washington continued to trust in “advantage of Works and Knowledge of the Ground,” reasoning that maintaining strong defensive positions was how the Americans had thus far mitigated British military might. Just days before the fall of Fort Washington, he observed to John Hancock, “It has been peculiarly owing to the situation of the Country where their [the British] Operations have been conducted, and to the rough and strong Grounds we possessed ourselves of and over with they had to pass, that they have not carried their Arms by means of their Artillery to much greater extent.”[13]

Experience had informed Washington’s conviction regarding strong defensive positions. Howe had, to this point in the war, declined to repeat the frontal assault on entrenched Americans—as at Breed’s Hill—on several occasions. In March 1776, when Washington secured Dorchester Heights, Howe abandoned Boston. In October, following the first day’s action at the Battle of White Plains, having secured Chatterton’s Hill, Howe then declined to assault the Americans entrenched on North Castle heights (earthworks erected with “magical swiftness,” according to Christopher Ward, because of their construction made up of cornstalks with the dirt-clods on the roots facing outward, created the illusion of strong works). And just about a month prior to White Plains, at Harlem Heights, Howe declined to conduct a direct assault as well. Ward explains Howe’s thinking best: “the American lines were too strong to invite a frontal attack. Nor was that Howe’s favored strategy. Circumvention was less costly and more nearly certain of good results.”[14]

Fort Washington sat on Harlem Heights, and Harlem Heights clearly fit the description of “rough and strong Grounds” extolled by Washington in his November 14 letter to Hancock. Writing to his brother, John Augustine, Washington noted how the “Heights of Harlem” were “well calculated for Defense against their approaches.” And while Washington could not have known, Howe also recognized how formidable the American works on Harlem Heights were, referring to them in a letter to Lord George Germain as “the very strong positions the enemy had taken on this [Manhattan] island and fortified with incredible labor.”[15]

The Americans had held the Harlem Heights against Howe once already. In his general orders of September 20, shortly after taking position on the Heights following the failure at Kips Bay and the panicked retreat from New York, Washington reassured his army: “The Heights we are now upon may be defended against double the force we have to contend with, and the whole Continent expects it of us: But that we may assist the natural strength of the ground, as much as possible, and make our Posts more secure, the General most earnestly recommends it is to the commanding Officers . . . to turn out every man they have off duty, for fatigue.”[16]

The “natural strength of the ground” must certainly have been in Washington’s mind in November 1776 on the eve of the assault on Fort Washington. Yes, Greene was overconfident about the American position. Yes, after the Pearl, the Joseph, and the British Queen passed up the Hudson River beyond the patriot obstructions, both Forts Washington and Lee were rendered irrelevant by the British Navy. But holding Fort Washington must still have been plausible enough in Washington’s mind for him to have been “Agreeable to the Advice of most of the General Officers, to risque something to defend the Post.”[17] He reconnoitered the situation on November 14, informing both Major General Lee and Maj. Gen. William Heath, “I was this day at Mount Washington and perceived some Incampment of the Enemy at, and near [Kingsbridge] but not very large.”[18] The commander-in-chief must have felt confident enough, because he left the next day, November 15, for Hackensack, New Jersey, six miles west of Fort Lee. His plan was to go further south to Perth Amboy. Then an urgent message arrived.

Greene sent notice to Washington that General Howe dispatched his adjutant general, Col. James Patterson, under a flag of truce to demand “Surrendry of the Garrison” at Fort Washington. The commander-in-chief raced back to his namesake fort to assess the situation first hand. Washington had only “partly crossed the North River” (the contemporary name for the Hudson), when he encountered Major Generals Israel Putnam and Greene returning from their own inspection of the garrison. There, bobbing somewhere mid-stream between New York and New Jersey, an impromptu war council took place.[19]

The “Troops were in high Spirits,” Greene and Putnam assured Washington, “and would make a good Defense.” In direct command of the fort was Col. Robert Magaw of Pennsylvania. In his response to the British demand of surrender, Magaw vowed he was “determined to defend this post to the last extremity.” Given these assurances by his senior officers, and the hour being late, Washington, Greene, and Putnam returned to Fort Lee. The fate of Fort Washington had been decided while floating in the Hudson.[20]

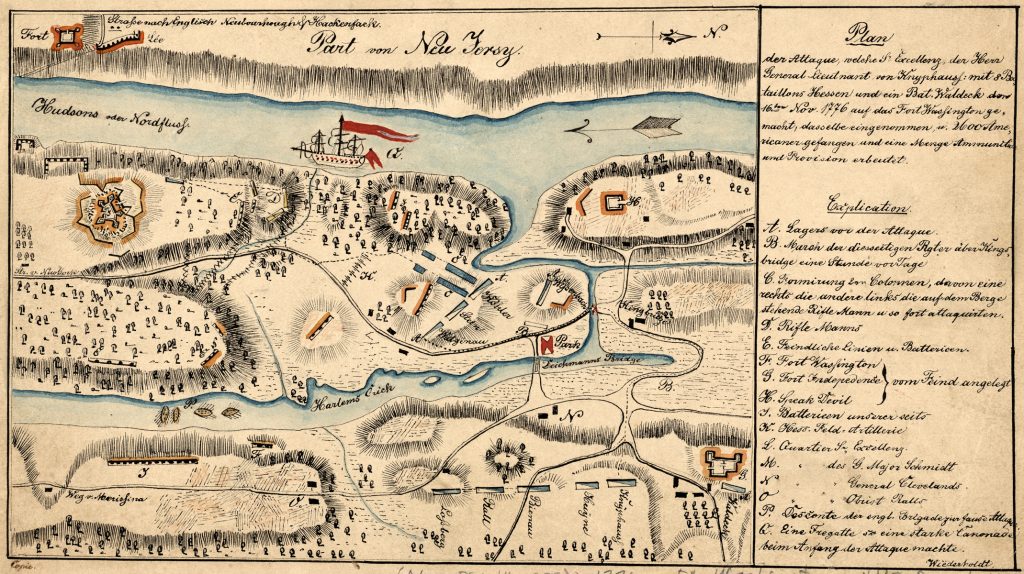

Howe launched his attack the next morning, November 16. He threw a massive force against the Americans. The ferocity of the assault could be heard nearly twenty miles away in Elizabeth Town, New Jersey, according to American Lt. James McMichael, who noted that “previous to our departure from Elizabeth we heard a heavy Cannonade at Fort Washington which we are Since informed of that the Enemy besieged it with their grand army.”[21]

It was that “grand army” of 13,000 British and German soldiers, organized in four columns, that swept over Harlem Heights. Magaw had deployed the Americans in the old defensive lines from when Washington had collected the entire force at the Heights back in September. At that time there had been 10,000 American troops occupying the ground, but now Magaw had only 2,900 at most in his command—too many for the fort to hold; too few to hold the lines. The mismatch was drastic. On Laurel Hill, east of the fort, 200 militiamen of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, attempted to delay the British 33rd Regiment, plus six battalions of light infantry, guards, and grenadiers. At a redoubt half-a-mile north of Fort Washington, Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings and 250 Maryland and Virginia riflemen held off 3,000 Hessian troops for nearly two hours. The constant firing eventually clogged the rifles, and the Americans were forced to retreat, carrying a wounded Rawlings and his wounded second-in-command, Otho Holland Williams, back to the fort. Williams, who what carrying his commission as a Continental major in his coat pocket, later annotating on the commission how it was “stained with blood” from his defense of Fort Washington, was one of several thousand whose lives were altered that day.[22]

The result for the Americans was devastating: 59 killed and 96 wounded in the action defending the fort; 230 officers and 2,607 soldiers made prisoner after capitulating. The loss in materiel (from both Forts Washington and Lee) was equally severe: 146 iron and brass guns of all sizes (including nine 32-pound guns and five 24-pound guns); 12,000 shot and shell; 15 barrels of powder; 2,800 muskets; 400,000 musket cartridges; hundreds of entrenching and armorers’ tools; tons of iron; and “a large quantity of other stores.”[23]

Much is made of Washington questioning Greene on November 8, 1776 as to whether it made sense to continue to hold Fort Washington, given that the passage of British vessels through the obstructions in the Hudson was “so plain proof of [their] inefficacy.” But, as noted above, the commander-in-chief then deferred to Greene on the question of withdrawing the garrison, given the latter was “on the spot.” However, Washington would be “on the spot” just five days later and had the chance to follow-through on his initial instinct to withdraw. Always a consensus builder, Washington had agreement from his second-in-command, Charles Lee, who at this point in the war was still held in high esteem. Lee had articulated that he saw “little or no use” in retaining Fort Washington during a November 6 council of war. Why after arriving on scene and reconnoitering the ground, did Washington not countermand Greene and pull off the garrison? Why would Washington side with an as-of-yet untested Nathanael Greene over a seasoned veteran like Charles Lee? Washington had to have also believed that the defense of Fort Washington was tenable, or at least, in his words, “agreeable . . . to risque something to defend the Post.” No amount of convincing by Greene, Putnam, or Magaw would have swayed Washington had he not also believed in the possibility that the ground was strong enough to be held. “General Washington appears to have had a good opinion of this post,” according to Alexander Graydon, “but though certainly strong by nature and improved by entrenchments in its most accessible parts, its eligibility, for any other purpose, than that of temporary encampment was very questionable.”[24]

Questionable indeed. Washington’s “good opinion” of the “strong ground” at Harlem Heights is what most likely influenced his actions (or inaction) leading up to the disaster of November 16, 1776. Nathanael Greene did not convince Washington to hold Fort Washington so much as confirm what the commander-in-chief already had in his head. In this light, the fall of Fort Washington was less the product of an “indecisive mind” and more the result of a miscalculated risk.

[1]David McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 243.

[2]Joseph Reed to Charles Lee, November 21, 1776, quoted in George F. Sheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It (Cleveland: World Publishing Co., 1957), 200; Lee to George Washington, November 19, 1776, in The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (PGW), Philander Chase, et. al, eds. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 7: 187; Lee to Horatio Gates, December 13, 1776, quoted in Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin Press, 2010), 263.

[3]Francis Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783 (Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop Publishing Company, 1914), 258-259; Alexander Graydon, Memoirs of a life, chiefly passed in Pennsylvania, within the last sixty years, with occasional remarks upon the general occurrences, character and spirit of that eventful period (Harrisburg: Printed by John Wyeth, 1811), 163.

[4]Edward G. Lengel, General George Washington: A Military Life (New York: Random House, 2006), 166; Chernow, Washington, 260; McCulloch, 1776, 235.

[5]Benjamin Huggins, “Washington’s Belated Admission,” Journal of the American Revolution, (April 23, 2014), allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/washington-belated-admission/

[6]Washington to John Hancock, November 16, 1776, PGW,7:163.

[7]Washington to Nathaniel Greene, November 8, 1776, PGW, 7: 115-116.

[8]Washington to Reed, August 22, 1779, PGW, 22: 224–227.

[9]Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats, 62-63; John Ferling, Almost A Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 57.

[10]General Orders, August 13, 1776, PGW, 6: 1.

[11]General Orders, August 23, 1776, PGW, 6: 110.

[12]Washington to Hancock, September 8, 1776, PGW, 6: 249.

[13]Washington to Hancock, November 14, 1776, PGW, 7: 155.

[14]Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952), 1: 255.

[15]Washington to John Augustine Washington, September 23, 1776, PGW, 6: 373; William Howe to George Germain, November 20, 1776, quoted in Henry B. Dawson, Battles of the United States: By Sea and Land: Embracing Those of the Revolutionary and Indian Wars, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War: with Important Official Documents, vol. 1 (New York: Johnson, Fry, and Company, 1858), 184.

[16]General Orders, September 20, 1776, PGW, 6: 348.

[17]Washington to Hancock, November 16, 1776, PGW, 7: 163.

[18]Washington to Lee and William Heath, November 14, 1776, PGW, 7: 159.

[19]Washington to Hancock, November 16, 1776, PGW, 7: 163.

[21]The Diary of Lieutenant James McMichael, 1776-1778, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 16, no.2 (1892), 138-39.

[22]Ward, The War of the Revolution, 1: 270-271; Commission “to be Major of the Regiment of Rifle Men whereof Hugh Stevenson Esq[ui]re is Colonel,” Otho Holland Williams Papers, MS 908, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

[23]Ward, The War of the Revolution, 1: 274; Peter Force, American Archives: Consisting of a Collection of Authentick Records, State Papers, Debates, And Letters And Other Notices of Publick Affairs, the Whole Forming a Documentary History of the Origin And Progress of the North American Colonies; of the Causes And Accomplishment of the American Revolution; And of the Constitution of Government for the United States, to the Final Ratification Thereof. In Six Series, Ser. 5 (Washington, DC: United States Congress, 1853), 3: 1058-1059.

[24]Washington to Greene, November 8, 1776, PGW, 7: 115-116; Ferling, Almost A Miracle, 149; Graydon, Memoirs, 153.

4 Comments

Most agree, with historical hindsight, that lack of gun powder was the key reason the Americans were unable to retain Breed’s Hill. But at the time the emphasis on American bravery was the story, and probably the one Washington heard upon taking command. The period of the British successful offensive at New York was horrible for Washington and there is a school of researchers who claim to have found clear indications of depression in his character at this time. I wonder how his mental state and lack of familiarity with the terrain affected his decision-making?

Odd that not a single general was left in command of Fort Washington. There were nearly 3,000 men. Normally that size of force would have had at least a Major General and a brigadier or two in charge of it. Instead we find Col.s Magaw (who commanded the interior works) and Cadwalader (who commanded the exterior works). Not one officer of general rank left to coordinate their actions. What is worse is that Washington and his staff (containing several such Generals) had abandoned the position immediately prior to the British assault, in full view of the men left to defend the place; escaping to Fort Lee in boats in time to observe the action on the far bank. As Cadwalader’s men were driven in, Magaw’s men did not come to their aid and counterattack. They simply sat within the fort making room for Cadwalader’s men until the place got so crowded it became untenable. At the end of the day no one was to blame, each had followed their orders, fought where they were supposed to. Whether Magaw’s presence would have reminded him of his scandalous abandonment of the place, or for some other reason, Washington refused to ever employ him again and he sat out the rest of the war ignored.

Wish there was more in this article or a future one of the actual battle at Fort Washington, including the soldiers and officers captured. After the Battle of Long Island many smaller battalions and regiments were reformed, so it is difficult to say who was where and when in my tracking of a single individual. However, it is valuable to note the disputes around the leadership at this particular time. CHB

One thing to note is that all but a few hundred men who surrendered at Fort Washington were from Pennsylvania. And, because they were then cooped up in the Sugar House (probably the worst atrocity of the war) and later on the prison hulks, fully half of them did not survive the war (the 600 or so who died in the sugar house incident didn’t survive the week). This was the deadliest incident to befall the state until the battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 (yes, I know Fredericksburg is in Virginia), and darn near took the state out of the war. The regiments of the following year had to be raised almost anew, their cadres having been destroyed by the surrender. The Associators and artillerists were especially hard hit, with the battalions of whole counties locked up. This could explain their rather lackluster performance in the 1777 Philadelphia campaign, especially compared to the New Jersey militia during the Forage War of 1776. Col. Magaw, himself, remained un-paroled in NYC until 1780 (Lambert Cadwalader was released after only a few days of captivity).