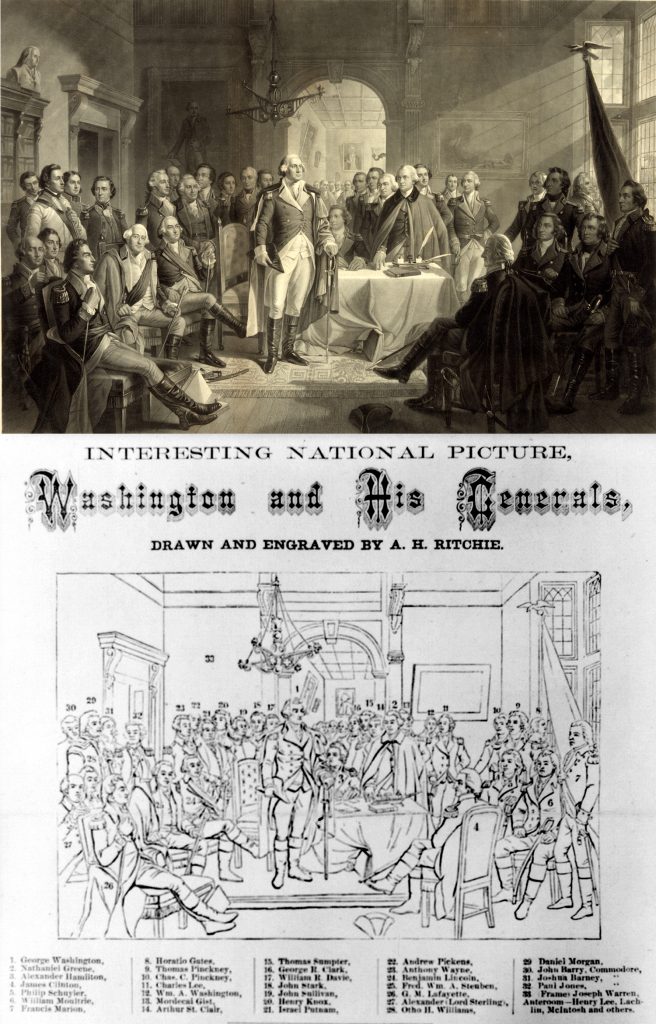

A.H. Ritchie’s 1856 engraving entitled “Washington and His Generals” is a creative, imaginary scene, as the dozens of generals shown assembled never congregated in such numbers in one place. For some odd reason, Ritchie depicted Maj. Gen. Charles Lee standing closest at the table with Washington, rather than the loyal and important Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene. Lee of course was put on trial for his insubordination at the outset of the Battle of Monmouth, whereas Greene was considered Washington’s most important major general and the chosen successor should the British capture Washington. Ritchie portrays Horatio Gates as he should be, not facing Washington at the table, but instead, looking out the window. This is to represent Gates as Washington’s foremost antagonist, as Gates tried several times unsuccessfully via Congress to have himself replace Washington as commander-in-chief.

Some people are under the impression that Washington’s famous farewell at Fraunces Tavern in New York on December 4, 1783 held the greatest concentration of generals, but that was not the case. Unfortunately, that was a dinner that was planned rather last-minute, and therefore those generals who did not accompany Washington for his ride from New Windsor Cantonment in upstate New York to his conference with British Gen. Sir Henry Clinton in Tappan, New York, were unable to attend the farewell at Fraunces. One notable of example of a senior officer not present was Alexander Hamilton, who, while not actively in the Continental Army at that late time in the war, was actually practicing law in Manhattan. One of the last active generals as of the fall of 1783, Brig. Gen. Jedediah Huntington of Connecticut, had been stationed in command of West Point, and received permission from Washington in October to return to Connecticut, partly because Huntington’s wife had complained of the increasingly cool weather.[1]

Maj. Benjamin Tallmadge famously recalled the event in his memoirs. His Excellency, General Washington, was certainly joined by Maj. Gen. Baron von Steuben and Brig. Gen. Henry Knox. They are well-documented as being the two generals remaining with Washington through the very end of the fall of 1783. The other two generals in attendance were Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall and Brig. Gen. James Clinton, both of New York.

So what, then, were the greatest concentrations of generals around Washington during the War for American Independence? The best source is a careful study of the scores of councils of war convened by General Washington, available through the Washington Papers.

The Beginning and the End

It appears that Washington’s first council of war was during the Patriot siege of Boston in July 1775. This council occurred on July 9, soon after Washington had arrived on July 3 with his adjutant, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, to take overall command of the fledgling Continental Army, thereby relieving Maj. Gen. Artemas Ward of command. The council was held at Washington’s first headquarters, the Benjamin Wadsworth House in Cambridge, which Washington occupied for the first two weeks of July. As worded and spelled in the minutes, in attendance were “Present His Exelly General Washington M[ajor] Generals Ward, Lee, Putnam” in the first column and in a second column, “B[rigadier] Generals Thomas, Heath, Greene, and Gates” They considered, among other topics, their army’s numbers and posture as they besieged the British regulars in Boston. Other, later war councils would involve Generals Washington, Gates and Greene. Benedict Arnold, though several times in attendance, was a colonel at that early time in the war.[2]

Shifting towards the end of the war, while it is not an actual council of war, it is relevant to mention briefly the Newburgh Conspiracy in March 1783 which necessitated Washington’s famous response with his “Newburgh Address” at the Hall or Temple. This was the largest building at the Continental Army cantonment in New Windsor, just south of Newburgh. It was here that Washington famously entered the officers’ meeting to address them. He gained their sympathy and put aside their plot for a military coup when they teared up watching Washington put on his reading glasses while he spoke of growing old and blind in the service of his country. Besides the obvious antagonist, Major General Gates, there were other generals in attendance, including Greene, von Steuben and Knox, but it does not seem that the number of generals approached the size seen in 1778 discussed later in this article.

Valley Forge and the Campaign of 1778

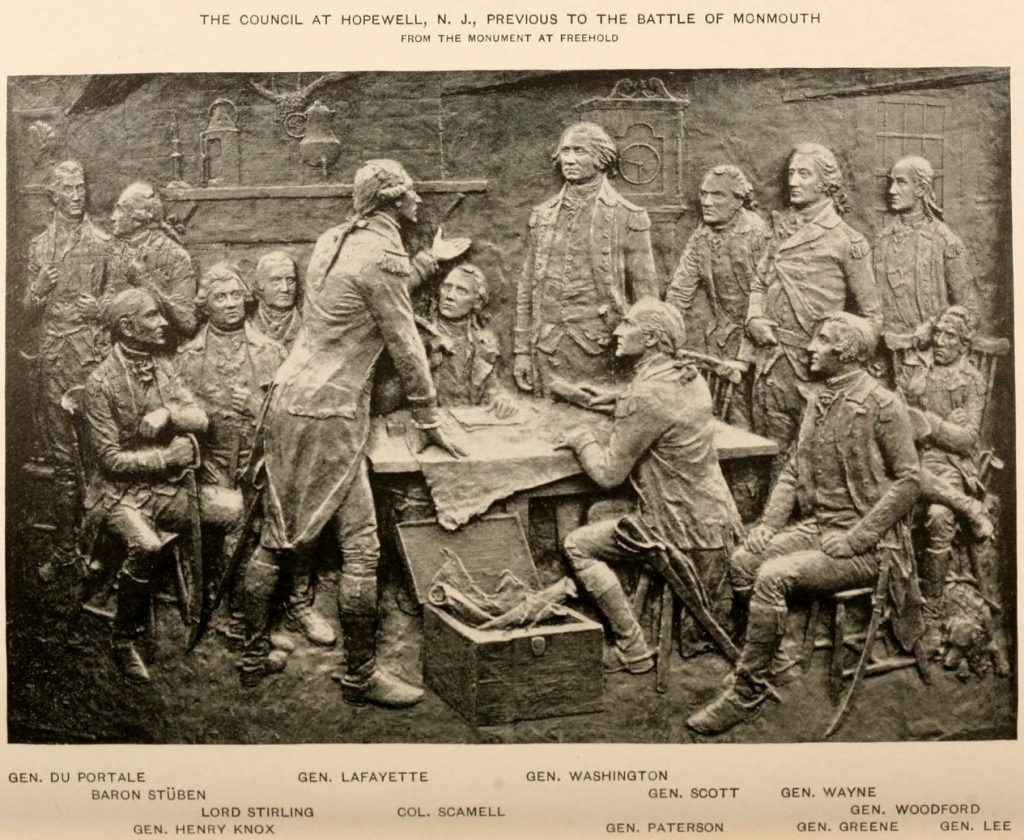

Washington’s war councils at Valley Forge and in southern New Jersey in the months leading up to the Battle of Monmouth had arguably the largest numbers of American generals congregated at any one time, and they did so several times that spring and early summer.

Perhaps the greatest (though not yet the most numerous) gathering of Washington’s generals during the war was just before the beginning of the 1778 campaign. Washington called for a war council on the 17th of June at Valley Forge as the Continental Army was preparing for action based on intelligence on the British in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and New York. It was a very packed room on the first floor of the stone Isaac Potts House and took place just two days before Washington left the house he’d been sequestered in for six months.

The list of generals who attended that meeting was a veritable “Who’s Who” of generals at the time, save for Gates and Sullivan, who were up north. The major generals included Washington’s rival, Charles Lee. Also present were Nathanael Greene, William Alexander, aka, “Lord Stirling,” the young Marquis de Lafayette, and the Baron von Steuben. Brigadier generals included William Smallwood, Henry Knox, Enoch Poor, John Patterson, Anthony Wayne, William Woodford, Peter Muhlenberg, Jedediah Huntington and Louis duPortail.[3]

What is particularly important and unique is that this gathering of generals also included Benedict Arnold, who of course would not deploy with the army in the campaign into New Jersey. He had been wounded in heroic action in Saratoga the previous fall and was recovering from his leg injuries while about to serve as military governor of the nearby city of Philadelphia. While still recuperating from his wounds, he was hobbling around and would have been at the meetings to offer his leadership not on the battlefield, but instead of the city recently abandoned by the British. It is interesting to note that, in an effort to weed out Loyalists, Washington had each of his soldiers and officers sign an oath of loyalty or allegiance. This occurred throughout the month of May, with Arnold signing his in the presence of Brigadier General Knox on May 30.

A second, similar council of war was called by General Washington a week later, on June 24. Since the Continental Army was already on the move from Valley Forge and into New Jersey, the council was held at Washington’s headquarters at the John Hunt House in Hopewell. Arnold understandably was not in attendance, and had likely returned to Philadelphia. Much like a week earlier, the major generals included Lee, Greene, Stirling, Lafayette and von Steuben. The brigadier generals included Knox, Poor, Wayne, Woodford, Patterson, Charles Scott and duPortail.[4] It is well worth noting that also in attendance was Washington’s closest aide and secretary of the minutes of these two meetings, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton would, upon the death of Washington in December 1799, become the highest-ranking U.S. Army officer, a major general during and just after the Quasi-War with France.[5]

Both councils of war that June revealed that Washington and his generals were torn between two interests: one was to fight; the other, to not suffer casualties. Most wanted some kind of “partial attack,” but everyone agreed that a “general action” should be avoided. The question was whether a “partial attack” would lead to a “general action.” As it turned out, the attack on the rearguard of the British led to the general action famously known as the Battle of Monmouth.

Later that summer, on September 1, 1778, Washington called for another well-attended council of war. By this time, Lafayette was already in Rhode Island with Maj. Gen. John Sullivan and other leaders for what had been the Battle of Rhode Island outside Newport that August. Washington had his headquarters at the Jacob Purdy House in White Plains for a total of just over six weeks. It was there that he was joined by six major generals (Putnam, Gates, Stirling, Lincoln, de Kalb and McDougall) as well as a thirteen brigadier generals (John Nixon, Samuel Parsons, James Clinton, William Smallwood, Knox, Poor, Paterson, Wayne, Woodford, Muhlenberg, Scott, Huntington and DuPortail) – likely the most of that rank ever at one place. It was an evening meeting, largely precipitated by General Sullivan’s letters from Rhode Island indicating that the French fleet had left the area to refit in Boston harbor as a result of damage they sustained during a violent storm off the coast. One of Washington’s key reasons for meeting was to discuss whether or not to attack New York. This was likely the first of what would be many conferences to address his penchant for wishing to attack the city.[6]

In the late summer of 1780, Washington had his headquarters primarily in northern New Jersey. While staying at the Zabriskie House in what is now River Edge, New Jersey, Washington called what seems to have been his final council of war with generals shortly before Arnold’s treason on September 25 at West Point. This council occurred on September 6, and according to the minutes, in attendance were “The Commander in Chief” along with “Major’s General” Greene, Lord Stirling, Arthur St. Clair, Robert Howe, Lafayette and von Steuben. The “Brigadiers General” included John Nixon, Clinton, Knox, John Glover, Wayne, Huntington, John Stark, Edward Hand and James Irvine.[7]

The Yorktown Campaign

While it was not an actual council of war, Washington’s return to Mount Vernon on September 9, 1781 for a three-day stay—his first there since—precipitated a visit from the French. Washington, his aides, Lt. Col. David Cobb and Lt. Col. David Humphreys, and his secretary, Lt. Col. Jonathan Trumbull were joined on the evening of September 10 by the Comte de Rochambeau and his staff. The next day they were joined by Maj. Gen. Francois-Jean de Chastellux and his staff.[8]

The several councils of war during the siege of Yorktown included, in addition to Washington, his second-in-command, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (the narcoleptic), as well as fellow major generals the Marquis de Lafayette (“the boy general” and commander of the Light Infantry Division), and the Third Division commander, Baron von Steuben. There was also the mass of Virginia militia commanded by Gen. Thomas Nelson of Yorktown. Continental Army brigadier generals included Henry Knox, James Clinton, Anthony Wayne, Mordecai Gist, George Weedon, Robert Lawson and Edward Stevens. Joining them in several conferences would have been the French leadership, headed by Lt. Gen. Comte de Rochambeau, along with Major Generals Charles Gabriel, Joseph Hyacinthe and Claude-Anne de Rouvroy de Saint Simon. The presence of two lieutenant generals, six major generals and many brigadiers makes this Franco-American collection arguably the greatest assembly of generals at any time during the war. Unfortunately, no minutes of any of these councils of war exist in the Washington Papers.

Returning to Ritchie’s illustration described in the beginning, perhaps the closest Washington and his generals came to imitating the large gathering of over thirty generals depicted would have been two of the conferences in 1778: the June council of war at Valley Forge or the later one, in early September, where Washington carefully weighed the various opinions of thirteen different brigadier generals in addition to six major generals.

[2]Council of War, July 9, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, The Papers of George Washington.

[3]Council of War, June 17, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, The Papers of George Washington.

[4]Council of War, June 24, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, The Papers of George Washington.

[5]William Gardner Bell, Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff, 1775-2013, (Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History Publication), 2013, 70.

[6]Council of War, September 1, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, The Papers of George Washington.

7 Comments

Damien: I much enjoyed the article and then was pleased to see you are a Hillsdale grad, as am I – Class of ’71

There appears to have been a gathering of many Generals in July 1780. in 2018, Gene Procknow wrote about a signature sheet of Generals I am fortunate to own and that was dated to July, 1780. You might find interesting: https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/08/unlocking-the-mystery-of-ten-revolutionary-generals-signatures/

I enjoyed your article very much. Thank you. I have been looking at Washington’s war councils in an effort to determine how much his reliance on them changed over the years. Was he less likely to accept and rely on their guidance and conclusions as the war progressed? Still looking.

The question of Greene as the chosen successor is a fascination one. There appears to be no written evidence that Washington ever suggested this to Congress, which is not surprising given his deference to that body, even if he felt that way. However, there is also no evidence that he didn’t share this view or suggestion behind the scenes with Congressional supporters. That seems to me to be more likely, but can’t be proven short of newly discovered evidence. If anyone has such, I would certainly like to see it.

But I would offer a two alternates to your Yorktown section. Both BG Lawson and BG Stevens were Virginia militia generals. While both had served as Continental officers, neither were Continental generals. You also suggest that there were two lieutenant generals at Yorktown – one being Rochambeau. That seems to suggest that Washington was the other. He wasn’t a lieutenant general, but rather a general, as per his commission from Congress. Check my JAR article on Washington’s rank. Sorry to nit pick.

Arthur StClair was another major general present at Yorktown, though he had no command and probably arrived too late to participate in any of the councils. But he does up your number. Thanks again.

Thanks Bill. That is a great question and a daunting task to analyze and somehow assess GW’s councils of war. I thought about writing a part two for this feature, but it would be too difficult to do such in a journal format. I had no idea about Gen. St. Clair at Yorktown. Since he didn’t take the field in command he’s overlooked by most scholars for that campaign. I really appreciate your feedback because you’re the expert on patriot generals. In fact, my seeing your talk on patriot generals at a Rev. War Roundtable years ago helped inspire me to write this piece. Look fwd to exchanging in emails.

“For some odd reason, Ritchie depicted Maj. Gen. Charles Lee standing closest at the table with Washington, rather than the loyal and important Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene.”

Sir, according to the accompanying key, Washington is joined at the table by Hamilton and Greene (both to his left) and Clinton (across the table). Lee appears to be way to the left of Greene. Am I reading the key correctly?

Great point, Cecilia. Thanks for catching that error. Yes, I went back to look at the key and it turns out you’re right that Greene is seated where I thought Lee sat. It is Horatio Gates that is looking out the window – a fine visual representation of his difference of opinion with most anything Washington suggested or requested. Perhaps Lee should have been standing next to Gates and joined him in looking out the window. I would have had Arnold peering in from outside, trying to eavesdrop! After all, in a letter from GW to Samuel Huntington, Washington stated that, in addition to the papers for the plans of West Point, those three militiamen had also found the latest minutes from a Council of War involving Washington in Andre’s boot.

Damien: I echo the sentiments already registered regarding your stellar article.

The headquarters house where the pre-Monmouth council at Hopewell still stands, although it is a private residence (and clearly marked that way along the borders of the property).

In my opinion, one of the more interesting councils commenced at the Henry Antes house near Pottsgrove, Pa., on September 23, 1777. It wasn’t the biggest, but 13 generals attended, with very revealing minutes taken by Greene and Lord Stirling. Washington presented two full-attack options only which eventually materialized as the Battle of Germantown. For added drama and irony, John Cadwalader and Thomas Conway were both at this meeting, the former as a headquarters visitor. Perhaps the next time those two got this close to each other was nine months later, on the 4th of July, when Cadwalader shot Conway through the mouth in a duel at Philadelphia.

While the article provides a general (no pun intended) discussion of a few selected councils of war, my personal preference would be to focus on Washington’s use of these councils to both solicit constructive input & feedback and examine His Excellency’s use of these Councils to garner some consensus on an issue or pending operation. Such a management style should be applicable even in today’s world. Living nearly in the shadow of the 21 Aug 1777 site where a Council of War discussed / debated a Continental military response to Howe’s anticipated Autumn offensive, I have relished reading through the various councils of war held during the late 1777 Philadelphia Campaign.

One source of potential interest on this topic is Worthington Chauncey Ford’s Defences of Philadelphia 1777 reprinted by Pranava Books, India which not only provides you with a war council’s minutes but also the written reports of several attendees (obtained from other sources) which were often then incorporated into Washington’s subsequent letter to the President of the Continental Congress on that War Council’s findings. Or you could simply directly turn to that final submission to Congress in Washington’s collected writings. This provides some direct insight into wartime strategy & operations planning. To me this is much more interesting than some later era portraits of Rev War military personalities.