On the 170th anniversary of Washington’s Birthday in 1902, the Delaware Society of the Cincinnati formed a procession of dignitaries and marched up Quaker Hill, the southwestern residential area of Wilmington. The ceremony continued to West Street, a north-south avenue named after an early settler. They stopped in the middle of a row of houses on the western side of the street, between 3rd and 4th streets. There at 303 West Street, the dignitaries unveiled a freshly inscribed bronze tablet which became the highlight of the February 22 event and was carried to the locale while wrapped in an American flag. The historical marker was affixed between and slightly below the two windows of the first story of the three-story front facing, where it remained for more than 60 years. According to its inscription, “This tablet marks the location of General Washington’s headquarters of the American army in Wilmington, Delaware.”[1]

During the ceremony the Delaware Society of the Cincinnati asserted that by “careful investigation by the best of authorities, gives absolute proof of this location as the one and only headquarters in the city of Wilmington.” Today that “absolute proof” has not come to light. With absolute certainty we do know that Washington headquartered in Wilmington during the last week of August 1777, and continuing for most of the first week of September. His official correspondences (mainly in the form of letters and orders) are simply headed “Wilmington” without any specifics added. No participant in the campaign identified the exact location of headquarters in Wilmington, neither in contemporary writings nor in post-war recollections. No Wilmington resident in an interview, diary, letter or reminiscence has ever stepped forward to claim that he or she housed General Washington; neither has a neighbor or relative of this host. The lone Wilmington receipt from this period is made out to a George Forsyth on August 27 for total charge of £63.12. A close inspection of the itemized charges reveals that it was primarily a very expensive two-day wine and meal bill (90 percent of the charges were incurred on Aug 25 and Aug 27) and not a lodging one. George Forsyth was not the homeowner or renter where Washington headquartered; he was likely a nearby tavern keeper who fed the general and his military family for the first few days in Wilmington.[2]

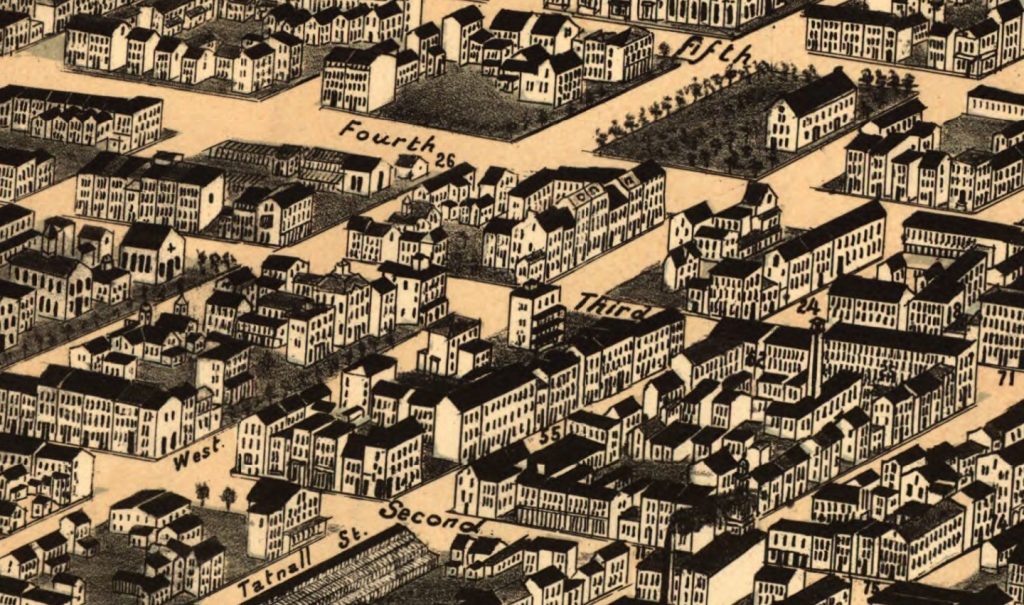

Like many “Washington-Slept-Here” claims, the house at 303 West Street where Washington headquartered in Wilmington has been identified by over a century of local hearsay and tradition. The house and (apparently) the tablet no longer exist. The last known photograph of the site was published in 1960. Miss Phoebe M. Hayes owned this house in 1902, but the locals back then knew it as the Gilpin House. Neither family name was associated with the house in 1777, a time when it was regarded as a mansion. It was built in 1748, part of a three-house contract for James Bartram & Company. Bartram was the first owner and resident of the house, which was eventually sold—or possibly rented—to Captain Jacob Bennett. In the late summer of 1777 Bennett, his wife, a son and at least three of his four daughters possibly lived there when Washington arrived Monday afternoon, August 25.[3]

The house was mapped, sketched, and photographed at least five times between 1868 and 1960, but the front facing West Street was altered so much that it linked with its neighbors on each side at 301 and 305 West Street with what a newspaper described as “a patchwork quilt of brick and frame additions with an assortment of roof angles and levels.” Notwithstanding the modern row-house façade that repeatedly is depicted in nineteenth- and twentieth-century images, the house where Washington resided for nearly two weeks in August-September 1777 was a sturdy, large, two-story independent structure with a red and black bricked pattern exterior. Captain Bennett’s probate inventory composed on March 10, 1782 gives us a rare peek at the belongings viewed (and some possibly used) by George Washington less than five years earlier, although the room layout of the house is unknown. These include a small frame stable and a “milch cow” outdoors, while inside Washington would have seen three walnut dining tables, a very valuable tea table and “eight day clock,” two spinning wheels, five beds, six “curled maple rush” chairs, two Windsor chairs, fifteen “rush bottom” chairs, a “rush bottom” couch, several mirrors (called “looking glasses”) of various sizes, and an assortment of china, pewter, and silver ware.[4]

Planting his headquarters at Wilmington, a city 26 miles from Philadelphia, on August 25—the very day Howe landed his armada below Head of Elk—strategically placed Washington nearly midway between Philadelphia and the British threat. With several waterways intersecting Delaware near Wilmington (Brandywine River, Red Clay Creek, White Clay Creek, and Christina Creek), Washington correctly hedged that a sound defensive position could be staked out within an hour’s horse trot from Wilmington. He clearly planned to block Howe’s shortest route to Philadelphia. Quaker Hill offered Washington the best view of the landscape between him and Howe compared to any other region of Wilmington.

Why Washington specifically chose the Bennett house is unknown. He had passed through Wilmington several times prior to the war and may have been familiar with Quaker Hill and Jacob Bennett from a previous visit or relationship. Bennett’s house did sit on the top plateau of the height. Although it was not a row house as nineteenth- and twentieth-century images suggest, considering this was not an overpopulated part of the city in 1777, it was still unusually close to the houses on each side of it, reducing its attractiveness as an isolated headquarters site. It also is noteworthy that the four miles that separated Washington’s headquarters from the closest flank of his defensively aligned army was not unreasonable, but indeed much more distant than most of his headquarters sites previous and subsequent to it during the summer and fall of 1777. This fact perhaps prompted Washington’s departure from Wilmington on September 6.

The largest headquarters staff to date worked for His Excellency between August 25 and September 6 on Quaker Hill. The constant seen here compared to previous headquarters personnel was the cadre of servants who toiled long hours each day at every Washington headquarters throughout the Revolution—black and white, male and female, young and elderly, free and enslaved. This included Washington’s manservant, William “Billy” Lee, his 73-year-old housekeeper, Elizabeth Thompson, his washerwoman, Margaret Thomas, and his cooking staff, including an African American man named “Isaac.” These servants had been considered hard-working and reliable; their Irish steward was not. His name was Patrick Maguire, a man who oversaw the servants since April but who Washington considered too insolent and too fond of liquor. Maguire still clung to his post for another six months after Wilmington until Washington finally dismissed him after accusing him of “taking every opportunity of defrauding me.”[5]

The aforementioned payment to George Forsyth reveals that eleven servants were served dinner on their first day at Wilmington. This separate line item helps to quantify the non-officered staff that worked for Washington as paid free persons as well as enslaved ones, but it may have also included some servants of aides to Washington.[6] Regardless, it was a substantial staff that attended to the general’s daily needs at his Wilmington headquarters.

A total of twenty-seven people ate dinner on August 25 as indicated under the heading “General Washington & Company Bill.” George Forsyth’s itemized receipt indeed indicates sixteen dinners in addition to the servants’ dinners. Congress authorized Washington to have a professional staff to include a military secretary, a job ably filled by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison, on Washington’s staff in some capacity since November 1775; an adjutant general, Colonel Timothy Pickering’s headquarters role since April 1777; and four aides-de-camp. At the time of the August 25 dinner, three of those appointed aides (all ranked lieutenant colonel) included John Fitzgerald, Alexander Hamilton, and George Kidder Meade. The fourth officially appointed aide-de-camp apparently not in attendance was George Johnston who was ailing with a lingering illness that would kill him in October.[7]

Including George Washington in Forsyth’s receipt accounts for only six of the sixteen dinners charged to headquarters. Although a name cannot be linked with each of the ten remaining dinners, we can still confidently identify at least six more of them—all of whom served as additional aides to George Washington. Through volunteerism, double duty, and transitional training, Washington was able to double his official staff and welcomed the additional talent and experience that accompanied him to Wilmington. Washington re-invented the role of aide-de-camp to not only handle traditional duties, but to also serve as “pen men;” that is, skilled in converting Washington’s dictated ideas into well-worded military documents.[8] Impressively, eight men penned letters and orders which Washington reviewed, edited, corrected, and eventually signed during those thirteen calendar days in Wilmington. All five of the allotted staffers did so, as well as two other experienced volunteers: Colonel Tench Tilghman and Captain Caleb Gibbs—as well as new trainee John Laurens. Peter Presley Thornton did not write for Washington, but he did serve as an aide-in-training at Wilmington. His Excellency officially announced the appointments of Laurens and Thornton in General Orders on September 6, identifying both as “Extra Aids du Camp to the Commander in Chief.” Both appointments became official the day Washington departed Wilmington.[9]

Two more dinners on the bill likely belonged to foreign generals either awaiting official appointment or waiting for an opening to command troops. The former described Casmir Pulaski, a Polish commander who Washington had already tagged to take over his currently headless brigade of Light Dragoons. Pulaski volunteered his services while he awaited this official appointment to come from Congress. The latter defined the Marquis de Lafayette. Quaker Hill tradition places him at 301 West Street during Washington’s occupation next door at 303. Congress had already appointed Lafayette as a major general, but he enthusiastically chose to serve Washington as a volunteer until he had a body of troops to command. Lafayette may have had two of his own aides in Wilmington (if so, they may have accounted for two of the remaining four dinners on August 25). When Lafayette departed Quaker Hill on September 6, he also departed his teenage years; Congress’s newest major general—the youngest appointed or commissioned officer of that rank in U.S. history—marked his 20th birthday that day.[10]

Major Generals Nathanael Greene and Adam Stephen participated in a daylong reconnaissance that began early on August 26 and therefore, are both good candidates to take up two more positions at the August 25 dinner table. Thus, the bill provided by George Forsyth reasonably enumerates Washington’s headquarters personnel. Washington’s staff had never been larger—perhaps as many as eleven servants and eleven army personnel: five of the allotted six staffers appointed by Congress plus an additional six aides—two skilled and experienced volunteers, two aides in training, and two foreign generals—comprised a headquarters staff numbering twenty-two that served George Washington routinely and daily in Wilmington, including a rotating staff position, the “Major General of the Day.” Dignitaries were also routine visitors to the Wilmington headquarters. (For example, John Laurens informed his father at the end of August that “Messrs. Pinckney and Horry arriv’d here yesterday. . .”) On any given day during the last days of August and the first days of September, up to thirty people were associated with Washington’s headquarters in Wilmington. Since the Bennett house could not fathomably house even half of them, tents, taverns, and townspeople likely provided shelter for much of the staff atop Quaker Hill.[11]

No major battle commenced during Washington’s stay in Wilmington. After a small and brief engagement at Cooch’s Bridge on September 3, Howe’s feint and flank on September 8 shifted both armies northward into Pennsylvania to set the stage for the Battle of Brandywine three days later. Most noteworthy about the 33,000 opposing soldiers in Delaware in that five-day interval is that for the first time in the war, Washington’s total available army of approximately 17,000 infantry, artillery, and cavalry officers and men (upwards of 14,000 Continentals plus 3,000 Pennsylvania and Delaware militia) was numerically on par with Howe’s 16,000 troops. That Howe was able to skillfully outmaneuver and out-battle Washington throughout early September was testament to the British commander’s tactical prowess and the lessons still needed to be learned by Washington and his command.[12]

Based on convincing secondary evidence, it appears a council of the generals of the Continental army commenced at Wilmington headquarters, likely on August 27, apparently to determine the best defensive positions for the army.[13] Most notable within one of these accounts is Washington shunning a repeated desire from vocal attendees at the council to launch a tactical offensive against Howe, thus thwarting the British commander’s hope to draw Washington into an ill-fated assault. Washington had not adopted a pure Fabian strategy (i.e., a War of Posts) but he did adhere to a tactical defensive with the large numbers of his reorganized army. He was resolved to engage in protracted battles at least starting on the defensive, hoping to inflict costly losses against Howe if attacked, as he had done to General Charles Cornwallis at Assunpink Creek on January 2. Washington’s decision to fortify his defense at Red Clay Creek rather than the more tempting high ground on the banks of the Brandywine four miles east of it was wise and fortuitous for it allowed Washington a fall back position on the Pennsylvania portion of the Brandywine after Howe turned his flank. [14]

On September 5, Washington issued his eleventh set of near-daily General Orders that he had crafted atop Quaker Hill. By 11:00 A.M. Colonel Pickering, by his duties as adjutant general, received those orders from the major general of the day, transferred those orders to the aides of all the division commanders and the selected majors of all the brigadier generals of the army. From there the orders traveled down to regiment and companies assembled in their Red Clay Creek works where they were read aloud. Copies of General Orders were recorded in orderly books.[15]

The September 5 orders were no different in the procedure by which they reached the ears of the privates in the army, but the contents of those orders distinguished them from the ten previous General Orders crafted in Wilmington as well as from and every other order written for 28 months before that. These orders went beyond the typical list of instructions and declarations. In a rare instance during the Revolution, George Washington had composed a challenge to his army intended to be witnessed by the American populace—intended for publication in newspapers after read aloud to his men. Appalled and prompted by a deposition detailing British atrocities near the Maryland-Delaware border as well as by Howe’s audacity to transfer his army the way he did, Washington informed America that the enemy’s intent was Philadelphia—“’Tis what they last year strove to effect; but they were happily disappointed.” Washington stressed that all was at stake for what he considered to be the make-or-break campaign. “Now then is the time for our most strenuous exertions,” pleaded His Excellency, following with a most uncharacteristic mix of aggressive and inspirational rhetoric to define what was at stake:

One bold stroke will free the land from rapine, devastations & burnings, and female innocence from brutal lust and violence. . . . Now is the time to reap the fruits of all our toils and dangers! If we behave like men, this third Campaign will be our last. Ours is the main army; to us our Country looks for protection. The eyes of all America and Europe are turned upon us, as on those by whom the event of the war is to be determined. And the General assures his countrymen and fellow soldiers, that he believes the critical, the important moment is at hand, which demands their most spirited exertions in the field. There glory waits to crown the brave–and peace–freedom and happiness will be the rewards of victory. Animated by motives like these, soldiers fighting in the cause of innocence, humanity and justice, will never give way, but, with undaunted resolution, press on to conquest. And this, the General assures himself, is the part the American forces now in arms will act; and thus acting, he will insure their success.[16]

These General Orders traveled 26 miles on a horse-backed courier to John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress. They were read to Congress to start out the September 6 session. John Adams informed his wife, “The General has harangued his army, and published in general orders, in order to prepare their minds for something great . . .”[17]

Washington’s stirring words first reached the eyes of the American public through the Pennsylvania Packet which published a large excerpt of the plea four days later. “A gentleman has favored us with the General Orders of our great and illustrious commander,” wrote the editors in preface; “the prop and glory of this Western World, issued to his Army . . . which we publish on account of the virtuous and noble sentiments they contain.” The Pennsylvania Gazette and the Post reproduced his remarks the following day in Philadelphia and distributed the issues within and beyond the city.[18] Unlike most of Washington’s previous orders, the Wilmington composition of September 5 spread through the colonies and continued to be published up to a month after they were first issued.[19] Washington’s thoughts, projected on paper in his and at least one of his talented aide’s words and prose at Wilmington headquarters, carried further and longer than most other non-battle documents he crafted during the course of the war.

Today, a visitor to the Quaker Hill neighborhood in Wilmington can visit the 1815 Friends Meeting House on West Street just north of 4th Street. The adjacent burial ground serves as the final resting place of Founding Father John Dickinson, known as the “Pen Man of the Revolution.” How ironic it is that less than a football field’s length south of this spot toiled nine talented “pen men” during two late-summer weeks of the Revolution, including and led by the ultimate Founding Father, in a house that no longer exists at a spot that is no longer marked.

[1]“Fine Tablet Now Marks Historic Old Mansion,” [Wilmington, Del.] Evening Journal, February 24, 1902, p. 7.

[2]Ibid.; George Forsyth to George Washington, August 27, 1777, George Washington Papers: Revolutionary War Vouchers and Receipted Accounts, 1776-1780, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[3]Fine Tablet Now Marks Historic Old Mansion,” [Wilmington, Del.] Evening Journal, February 24, 1902, p. 7; “Research Bares New Data on Washington’s Quarters,” [Wilmington] Morning News, February 22, 1957, p. 45; Jacob Bennett family im https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/KKR2-T45/jacob-bennett-1728.

[4]Wilmington, Delaware State Atlas, Pomeroy & Beers, 1868, http://www.historicmapworks.com/Map/US/4652/Wilmington/Delaware+State+Atlas+1868/Delaware/; Wilmington, Delaware, 1874, Bird’s-eye-view, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3834w.pm001060/; “Some Houses Washington Visited . . .,” Wilmington Morning News, February 18, 1950, p. 18; “Historic Landmarks,” [Wilmington, Delaware] News Journal, October 2, 1954, p. 14; “Blighted Headquarters,” Wilmington Morning News, February 22, 1960, p. 5; “Fine Tablet Now Marks Historic Old Mansion,” [Wilmington, Del.] Evening Journal, February 24, 1902, p. 7; Captain Jacob Bennett Probate Inventory, March 10, 1782, in http://www.math.udel.edu/~rstevens/datasets/nccprobate/bennett_jacob.html.

[5]Arthur S. Lefkowitz, George Washington’s Indispensable Men: The 32 Aides-de-Camp Who Helped Win American Independence (Mechanicsburg, Pa: Stackpole Books, 2003), 70-71, 332; George Washington to Thomas Wharton, April 17, 1778 in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2004), 14: 543. (PGW)

[6]George Forsyth to George Washington, August 27, 1777, George Washington Papers. One of the aide’s enslaved servants was “Shrewsberry.” See John Laurens to Henry Laurens, August 21, 1777, in William G. Simms, ed., Colonel John Laurens in the Years 1777-8(New York: Bradford Club, 1867), 58.

[7]George Forsyth to George Washington, August 27, 1777, George Washington Papers; Lefkowitz, Washington’s Indispensable Men, 15, 59, 104; Octavius Pickering, The Life of Timothy Pickering, Volume 1 (Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1867), 129, 152-53.

[8]Lefkowitz, Washington’s Indispensable Men, 8.

[9]General Orders, September 6, 1777; PGW 11:157-58. Other than adjutant Pickering and secretary Harrison, evidence of six other “pen men” at Wilmington can be seen in PGW 11: 64, 71, 75, 78, 80, 104.

[10]Washington to John Hancock, August 28, 1777, PGW 11: 85; Lefkowitz, Washington’s Indispensable Men, 124.

[11]John Laurens to Henry Laurens, August 30, 1777, Colonel John Laurens in the Years 1777-8, 59.

[12]For a breakdown of estimated numerical strength by division, see Michael C. Harris, Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777(El Dorado Hills, Calif: Savas Beatie, 2014), 168-73, 177.

[13]For indirect evidence of the Council, See: Muenchhausen diary, September1, 1777, in Ernst Kipping and Samuel Stelle Smith, eds. At General Howe’s Side 1776-1778: The diary of William Howe’s aide de camp, Captain Friedrich von Muenchhausen. (Monmouth Beach, N.J: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 27; William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment, of the Independence of the United States of America(Vol. 2), 494-495. Nathanael Greene’s grandson and biographer cited a letter from Gordon to General Greene, dated April 5, 1784, as the evidence that General Greene was Gordon’s authority. See George Washington Greene, The Life of Nathanael GreeneVolume 1 (New York: G. P. Putnam and Son, 1867), 444 (n#2).

[14]For indirect evidence of the Council, See: Muenchhausen diary, September1, 1777, in Ernst Kipping and Samuel Stelle Smith, eds. At General Howe’s Side 1776-1778: The diary of William Howe’s aide de camp, Captain Friedrich von Muenchhausen. (Monmouth Beach, N.J: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 27; William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment, of the Independence of the United States of America(Vol. 2), 494-495. Greene’s grandson and biographer, George Washington Greene, cites a letter from Gordon to General Greene, dated April 5, 1784, as the evidence that General Greene was Gordon’s authority. See George Washington Greene, The Life of Nathanael GreeneVolume 1 (New York: G. P. Putnam and Son, 1867), 444 (n#2)

[15]Lefkowitz, Washington’s Indispensable Men, 72

[16]General Orders, September 5, 1777, PGW 11: 147-48.

[17]John Adams to Abigail Adams, September 8, 1777, in Charles F. Adams, Familiar Letters of John Adams and His Wife Abigail Adams During the Revolution with a Memoir of Mrs. Adams

(New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1876), 305.

[18]Pennsylvania Packet, September 9, 1777; Pennsylvania Gazetteand Pennsylvania Post, September 10, 1777.

[19][Baltimore] Maryland Journal, September 16, 1777; [Boston] Independent Chronicle, September 18, 1777; [Hartford] Connecticut Courant, September 22, 1777 & Norwich[Conn.] Packet, September 22, 1777; [Portsmouth] New-Hampshire Gazette; [Williamsburg] Virginia Gazette, September 26 & October 3, 1777.

2 Comments

Nice job.

Good story, remarkable details.