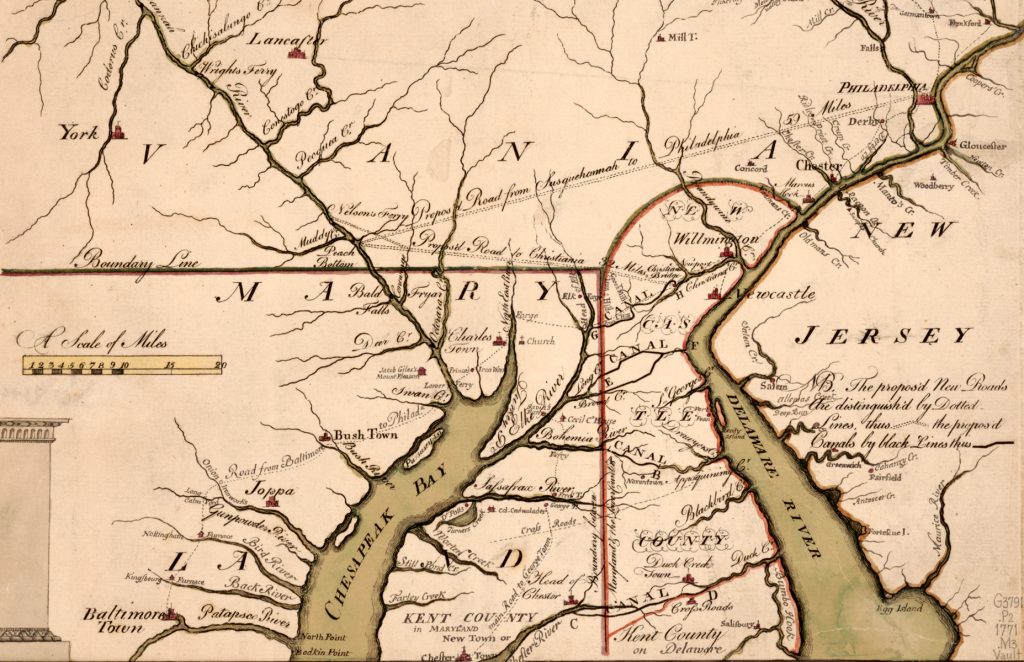

The Philadelphia Campaign of 1777 took definitive shape when Gen. William Howe successfully landed his 16,000 officers and men near Head of Elk (now Elkton), Maryland, on August 25, 1777, the very day that Washington set up his headquarters at a house atop Quaker Hill in the southwestern portion of Wilmington, Delaware, while his advanced two divisions of the Continental army nestled into place a few miles behind him. Wilmington sat half way (twenty-six miles) between Howe and Philadelphia. All four of the brigades within those divisions consisted of Virginia-only infantry regiments. “I propose to view the grounds towards the Enemy in the morning,” wrote Washington to John Hancock on that Monday, admitting his ignorance of the lay of the land when he added, “I am yet a stranger to them [the grounds].”[1]

The next day Washington conducted a thirty-six-mile round-trip reconnaissance to Head of Elk, returning the following morning (August 27) to his new Quaker Hill headquarters. This Washington-led mission is often described in biographies of Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Nathanael Greene (two of the other participants), and in most accounts of the Philadelphia campaign. To date the sole primary source describing the August 26 reconnaissance referenced in all of these secondary sources has been this brief description by Washington in a letter to John Hancock written on August 27:

I this morning returned from the Head of Elk, which I left last night. In respect to the Enemy, I have nothing new to communicate. they remain where they debarked first. I could not find out from inquiry what number is landed—nor form an estimate of It, from the distant view I had of their Encampment, But few Tents were to be seen from Iron Hill and Greys Hill, which are the only eminences about Elk. I am happy to inform you, that all the Public stores are removed from thence, except about seven thousand Bushels of Corn. This I urged the Commissary there to get off as soon as possible, and hope it will be effected in the course of the few days.[2]

Washington included an even briefer clarification to Landon Carter, a Virginia confidant, on October 27:

I was acting precisely in the line of my duty, but not in the dangerous situation you have been led to believe. I was reconnoitring, but I had a strong party of Horse with me. I was, as (I afterwards found) in a disaffected House at the head of Elk, but I was equally guarded agt friend and Foe. the information of danger then, came not from me.[3]

The rest of the first-hand view of the Head of Elk Reconnaissance comes from this 1779 recollection of the Marquis de Lafayette (Note his two-year-old memory mistakenly places the reconnaissance on August 25 instead of August 26):

The same day that the enemy landed, General Washington imprudently exposed himself to danger. After a long reconnaissance he was overtaken by a storm, on a very dark night. He took shelter in a farmhouse, very close to the enemy, and because of his unwillingness to change his mind, he remained there with General Greene and with M. de Lafayette. But when he departed at dawn, he admitted that a single traitor could have betrayed him.[4]

The common thread in Washington’s October statement and Lafayette’s reminiscence is that Washington chose to overnight dangerously close to the British position. Little else is repeated, but the additive value of all three accounts (two by Washington and one by Lafayette) provides us with the composition of the reconnaissance as Washington, Lafayette, Greene (presumably accompanied by aides). Washington’s claim of “a Strong party of horse” is confirmed by Timothy Pickering, Washington’s adjutant, who did not accompany them but wrote that all but one regiment of the light horse brigade trotted out that day.[5] The route from Wilmington to Head of Elk included a stop near Christiana Bridge, as proven by a voucher written by Alexander Hamilton for breakfast there.[6] The old road from Christiana to Head of Elk passed by Iron Hill and Grey’s Hill, which dovetails with Washington’s account. Finally, Lafayette stated that they began their return at dawn and Washington indicated that they completed the return sometime during the morning hours of August 27.

British diarists add some more specifics, albeit somewhat limited by hearsay. From General Howe’s newest headquarters at Head of Elk, his aide de camp told his diary on August 28, “General Washington spent several days in the same house where we are now lodging, and did not leave it until yesterday morning.”[7] (The “several days” claim is the only inaccurate statement in this passage.) Similarly, Maj. John André wrote in his journal on August 28 about Head of Elk: “Washington had been there on the 27th and dined at the house now General Howe’s headquarters.”[8] Andre did not claim that Washington made an overnight stay in the house.

Today, two structures still exist in Elkton that are claimed to have been headquarters used by both Washington and Howe. Hollingsworth Tavern stands at 205 Main Street and was known as Elk Tavern in 1777. Campaign authors and historical publications credit this stone building as the headquarters site.[9] The Hermitage, one mile east of it, is also claimed to be the site, complete with a Maryland Historical Marker to that effect. This claim is supported by the August 28 journal entry of Lt. Francis Downman of the Royal Artillery, who “was informed by a sick man who ventured to stay in” the Hermitage where Washington had dined two days earlier.[10] This entry was persuasive enough for a recent historian to name it as the site where Washington dined and stayed overnight on August 26.[11] Both of these historic sites in Elkton, however, have relied solely on tradition without one 1777 source or post-campaign reminiscence to strengthen the case for their respective claims.

At least one historian has been influenced by André’s and Lafayette’s account to claim that Washington dined at one residence on August 26 but stayed in another overnight. John F. Reed, in Campaign to Valley Forge, states that Washington took “Generals Greene, Lafayette and Weedon, with a small escort of horse” to Iron Hill, then to Grey’s Hill before heading into the Head of Elk community. He places Washington in Elk Tavern for a meal but questions the validity of this tradition, believing it to be strongly challenged by Washington’s prudence about being so close to his enemy. Reed’s version has Washington distancing himself from Head of Elk and spending the night in a different house than where he dined. Reed places the farmhouse Lafayette alludes to at the base of Iron Hill, five miles east of Head of Elk. He writes that the lady of the house did not know who Washington was, and has all three—Washington, Lafayette, and Greene (Weedon disappears from the account) sleeping on a hard floor wrapped in their wet cloaks.[12] Reed’s vivid description of the sleeping arrangement has no attribution, but he appears to expand on a passage from Nathanael Greene’s biographer and grandson: “Night came upon the little party as they turned their horses’ heads homewards and with it a sudden tempest of wind and rain. Washington sought with his companions the shelter of a neighboring farm house. It was a gloomy evening, with the black storm without and the crowded room within, clothes drenched with rain.”[13]

Nearly twenty years ago, I came across an excerpt of a letter written by a Revolutionary War soldier early in the Philadelphia campaign in August 1777. The excerpt was published in a Virginia newspaper about ten days after it was written, but apparently has not been noticed since. Although the newspaper is now readily available in digital form through an online subscription, to the best of this author’s knowledge the letter has not been referenced in any secondary source about George Washington and the Philadelphia campaign.

On page two of the September 5, 1777 edition of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette(a four-to-six-page weekly paper), the heading to the August 27, 1777 extract indicates it was written by “major Forsyth, aid de camp to major general Stephen.”[14] This refers to Robert Forsyth, aide to Maj. Gen. Adam Stephen, one of George Washington’s five division commanders at the start of the Philadelphia campaign. It appears that Forsyth’s letters were sent to a Williamsburg-area friend or family member who offered his eyewitness accounts to Alexander Purdie, the paper’s owner and chief editor. Two weeks later the excerpt found its way into the New Bern North-Carolina Gazette.[15] It appears not to have surfaced anywhere else since then.

Robert Forsyth’s rank as “major” reflected his position as an aide-de-camp. He was born in Scotland twenty-three years before the Philadelphia Campaign, moved with his family during his teenage years to New England and then to Fredericksburg, where he joined in the 4th Virginia Regiment as its adjutant in 1776. After his service in the Philadelphia Campaign, he became a dragoon captain under Maj. “Light Horse” Henry Lee. He resigned from the Continental Army and was commissioned major in the Virginia militia in 1781. In 1789, President George Washington appointed Major Forsyth the first U.S. marshal of Georgia. Forsyth earned the unfortunate distinction as the first U.S. Marshal killed in the line of duty five years later at the age of forty. In 1981, the U.S. Marshals created a service award in Robert Forsyth’s honor.[16]

At first glance (or even a second or third), nothing in Forsyth’s August 27, 1777 letter extract jumps out at the reader to indicate that the missive has any value. It is, however, the only contemporary account of the Head of Elk Reconnaissance besides Washington’s August 27 letter.

Robert Forsyth’s August 27 letter about the previous day’s mission does not detail the full day’s activity, but provides enough insight to confirm some of the traditional claims, refute others, and provide some new pearls to improve our understanding of what took place that day—beginning with the very first sentence of the published extract: “Yesterday his Excellency, and most of his general officers, with a good many light horse, left Wilmington to reconnoiter the country below this.” Forsyth’s description makes this reconnaissance a larger expedition than any account before this. He claimed “most of” Washington’s generals accompanied him. The two Virginia divisions of Continentals encamped around Quaker Hill included two major generals (Nathanael Greene and Adam Stephen) and four brigadier generals (Peter Muhlenberg, George Weedon, William Woodford and Charles Scott). Forsyth’s “most of” suggests at least four of these and perhaps all six took part in the reconnaissance, as well as Gen. Lafayette and a host of aides. Forsyth’s next sentence begins, “We were down as far as the Head of Elk,” confirming that he was a participant on the expedition; we can assume that his boss, Gen. Adam Stephen, took part as well.

Forsyth went on to explain that British troops were carrying off public stores at Head of Elk and that “the militia turn out with great spirit, and patrol down” toward Cecil courthouse, opposite where “a large body of the enemy have landed.” His next sentence contains two gems: “Whilst we were dining at Mr. Alexander’s, at the Head of Elk, an express arrived from General Sullivan, with letters for his Excellency, of the 24th of August.”

“Mr. Alexander” was Robert Alexander, a Baltimore lawyer and former member of the Sons of Liberty and a Maryland delegate to the Second Continental Congress in 1776.[17] He owned the home later called “The Hermitage,” the residence one mile east of Elk (Hollingsworth) Tavern.[18] Forsyth’s account confirms the accuracy of today’s historical marker in front of the 285-year-old house at 323 Hermitage Drive and vanquishes Hollingsworth Tavern as Washington’s dining site. Does this also confirm Howe to have stayed at the same locale, or could he have stayed at Elk (Hollingsworth) Tavern? Forsyth’s letter cannot possibly determine this, but the repeated assertions by British diarists—particularly from Lt. Downman who identified “a Mr. Alexander at whose house our General resides”—make a strong case that Washington dined and Howe headquartered at the Hermitage.[19]

Forsyth described not one letter, but instead “letters” written on August 24 by Maj. Gen. John Sullivan and delivered to Alexander’s by “an express.” Indeed, from his headquarters in Hanover, New Jersey, Sullivan wrote two letters that day to Washington; together the communications totaled 1,750 words.[20] Not only did it require hours for Sullivan to compose the letters, the events he detailed in them included activities that occurred that day. It is reasonable that Sullivan handed off the completed letters for delivery no earlier than noon that day and perhaps even later. No fewer than 130 miles of road, bridge, ford, and ferry sprawled between Sullivan’s headquarters and Alexander’s where Washington received them. The express Forsyth mentioned truly did deliver Sullivan’s reports quickly and efficiently. That the courier was directed to Mr. Alexander’s to deliver the message provides some evidence that Washington was in that house much longer than just for a meal.

More than half of the published portion of Forsyth’s letter is dedicated to Sullivan’s August 22 raid on Staten Island, obviously indicating that Forsyth was privy to the contents of the dispatches Washington received from Sullivan. Forsyth’s mention of “3 or 400 more [British troops] must have been wounded,” is information included 1,400 words into Sullivan’s longest letter. That a division commander’s aide de camp was this knowledgeable about the entire contents of a different division commander’s letter to Washington indicates that those letters were shared with other generals and aides involved in the reconnaissance. This provides even more evidence that Alexander’s residence was much more than a stopping place for Washington to get a meal and be on his way.

Notwithstanding John Reed’s fanciful account of Washington sleeping on a hard floor, wrapped in his wet cloak, in a farmhouse at the base of Iron Hill on the night of August 26-27, it is more likely that Washington remained at Alexander’s overnight. The residence was large enough to house all of the generals and their aides (particularly if it subsequently proved a suitable site for the British general and his substantial staff). Neither Forsyth nor Lafayette suggested that the residence where they dined was different from the residence where they slept (Lafayette never mentioned stopping to dine and Forsyth never mentioned going somewhere else to sleep). Furthermore, Lafayette’s description of Washington—“He took shelter in a farmhouse, very close to the enemy, and because of his unwillingness to change his mind, he remained there with General Greene and with M. de Lafayette . . . he departed at dawn”[21]—suggests that Lafayette urged Washington to reconsider due to how close they were to the British army (less than eight miles from Alexander’s to Howe’s landing site). That urging would have been less important if they had already distanced themselves another five miles east from Head of Elk and slept at the base of Iron Hill.

Washington’s letter to Landon Carter two months later attempting to minimize his recklessness on August 26 is also revealing evidence of his overnight stay at Alexander’s house. “I was, as (I afterwards found) in a disaffected House at the head of Elk,” His Excellency explained.”[22] Washington’s parenthetical statement assumes he did not knowingly enter the house of a Loyalist, but discovered this sometime in the subsequent two months.

Robert Alexander perfectly fits into Washington’s revealing passage. Believing that Robert Alexander was strongly aligned with the Patriot cause when Washington and his generals migrated to his home that rainy late afternoon or evening, Washington likely learned that Alexander was not the ardent patriot he believed him to be from his past history as a former Son of Liberty and 1776 member of the Continental Congress. During Howe’s occupation of Head of Elk, Alexander turned out to be much more than a typical turncoat. Not only did he ally with the British during Howe’s apparent conversion of his home to British headquarters in late August, on September 8 he left his patriot wife and their children behind by sailing on one of Lord Richard Howe’s ships that eventually deposited him into Philadelphia. Alexander moved with the British to Loyalist-laden New York in 1778 and then moved permanently (and alone) to London in 1783, three years after he was officially branded a traitor by the state of Maryland resulting in two thirds of his estate and half of his slaves being confiscated and sold.[23]

Forsyth ended his letter with assurance that the men were in good spirits and “if Howe should attempt to take a walk into the country he will be apt to lose a leg or an arm.” He matched his heading of “Christiana bridge” and his closing that “We only stop here to take breakfast, and then set off for Wilmington.” This tells us that Forsyth’s letter was written ten miles from where he returned from the reconnaissance, a little over halfway between headquarters on Quaker Hill and Head of Elk. Washington returned to his new Wilmington headquarters before the morning was over on Wednesday, August 27.[24]

In addition to definitively placing Washington’s reconnaissance party at Alexander’s, the most revealing historiographical contribution of Forsyth’s letter is that “most of the general officers” accompanied Washington on the Head of Elk reconnaissance. A published receipt sheds more light on this. On September 2, 1777 Alexander Hamilton issued a receipt to Capt. Caleb Gibbs, the commander of Washington’s Life Guard probably serving as an aide to Washington on this mission, for lodging “in Cecil August 26.” Hamilton attached to it the breakfast bill for August 26 near Christiana Bridge, in Hamilton’s own writing. The bill included Rum and five breakfasts for servants, “Spirits” on a separate line, and at the top of the bill eighteen more breakfasts—presumably for the non-servants dining there.[25] This impressively large party at that breakfast table supports Forsyth’s contention that the reconnaissance included “most of his general officers”: Lafayette and Washington plus at least four other generals, Hamilton and at least one aide for each of the generals, and a few other staff members.

Why did Washington bring himself and his top personnel along on a reconnaissance that could have been accomplished by dragoons alone? Certainly it wasn’t just to gaze upon Howe’s army and discern its composition. The most logical reason for Washington to include all of these generals in his reconnaissance was to put as many leaders’ eyeballs as possible on the terrain between Wilmington and Howe’s landing site in an effort to plan the best defense against Howe’s advance. It cannot be ruled out that Washington held a council of those generals at Alexander’s house to get their input regarding the best areas of defense.

Throughout the first six months of 1777, Washington and his Continentals with the very beneficial aid of the New Jersey militia had successfully locked General Howe and his army in position behind the Raritan River in northeastern New Jersey, sixty road miles from Philadelphia. Howe’s landing site below Head of Elk on August 25 stood fifty-two road miles from the city. Faced with strikingly similar circumstances, Washington’s top priority was to be as meddlesome to Howe during the last third of 1777 as he was throughout the first half. That Howe successfully advanced his army beginning on August 28 from Maryland to Delaware and then into Pennsylvania to seize Philadelphia in thirty days—and could have done so ten days sooner had he chosen to—when he could barely budge for twenty-six weeks in New Jersey earlier in 1777 is a telling mark of failure for Washington and his subordinates charged with the duty to prevent that from happening. Thus, Washington’s August 26 Head of Elk reconnaissance, notwithstanding the impressive participation of his subordinates, proved to have no impact on the outcome of the Philadelphia Campaign.

[1]George Washington to John Hancock, August 25, 1777, in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 11: 69 (PGW).

[2]Washington to Hancock, August 27, 1777, PGW, 11: 78.

[3]Washington to Landon Carter, October 27, 1777, PGW, 12: 25-27.

[4]Lafayette’s Memoir, 1779, in Stanley J. Idzerda, et al., eds. Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977), 1: 92.

[5]Timothy Pickering Journal, August 26, 1777, in Octavius Pickering, ed., The Life of Pickering (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1867), 1: 152.

[6]“General Washington’s Bill,” August 26, 1777, in Harold C. Syett et al, eds., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979), 26: 363.

[7]Ernst Kipping and Samuel Stelle Smith, eds., At General Howe’s Side 1776-1778: The diary of William Howe’s aide de camp, Captain Friedrich von Muenchhausen. (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 26.

[8]John Andre, Major Andre’s Journal (Tarrytown, NY: William Abbatt, 1930), 38.

[9]Gerald J. Kauffman and Michael R. Gallagher, The British Invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777: A watershed Moment in American History (published by the authors, 2013), 17-18.

[10]F. A. Whinyates, ed., The Services of Lieut.-Colonel Francis Downman, R.A. in France, North America, and the West Indies, Between the Years 1758 and 1784 (Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1898), 30.

[11]Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume 1: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006), 141, 359n81.

[12]John F. Reed, Campaign to Valley Forge: July 1, 1777-December 19, 1777 (London: Oxford University Press, 1980), 84-85.

[13]George Washington Greene, The Life of Nathanael Greene, Major-General in the Army of the Revolution (New York: G. P. Putnam and Son, 1867), 1: 443-44.

[14]Virginia Gazette(Purdie), September 5, 1777.

[15]North-Carolina Gazette, September 19, 1777.

[16]Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army(Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop Publishing Company, 1914), 233; F. A. Weyler, transcriber, Robert Forsyth Pension Papers, R14237, www.revwarapps.org/r14237.pdf; Katie Lebert, “Connections to Local History: A Short Biography of Robert Forsyth,” washingtonpapers.org/short-biography-robert-forsyth/; “The First Marshal of Georgia: Robert Forsyth,” www.usmarshals.gov/history/firstmarshals/forsyth.htm. Decades later his son John earned distinction as the governor of Georgia and the Secretary of State for Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin van Buren.

[17]“Robert Alexander (1740-1805),” Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series) msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/000001/000017/html/alexander.html; “A Maryland Loyalist,” Maryland Historical MagazineVol 1, No. 4 (December 1906), 317.

[18]Erika Quesenbery Sturgill, “The ‘frien-emy’ of Friendship in Elkton,” May 9, 2015, www.cecildaily.com/our_cecil/the-frien-emy-of-friendship-in-elkton/article_2e845e59-4d3a-51dd-bdcb-d040fc2352b7.html.

[19]Whinyates, ed., The Services of Lieut.-Colonel Francis Downman, 30.

[20]John Sullivan to Washington, August 24, 1777 (2), PGW, 11: 57-63.

[21]Lafayette’s Memoir, 1779, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 1: 92.

[22]Washington to Landon Carter, October 27, 1777, PGW, 12: 25-27.

[23]“A Maryland Loyalist,” 321-23.

[24]Washington to Hancock, August 27, 1777, PGW, 11: 78.

[25]Receipt to Captain Caleb Gibbs and “General Washington’s Bill,” August 26, 1777, in Syett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 26: 363.

2 Comments

Great detective work and a highly engaging article! During the reconnaissance, the participants must have been thinking of the capture of Maj. Gen. Charles Lee. Fortunately for Washington and his party, the British were woefully short of horses due to the extended and stormy sea passage.

Brandywine is one of the few battles that the Rebels did not enjoy the benefit of local support and knowledge. I wonder if that was the reason Washington took a considerable risk and conducted personal reconnaissance. Further, he suffered from considerable misinformation over the past weeks and sought to personally confirm the size and disposition of the enemy before positioning his forces and offering battle.

As a result of the survey mission, at least Washington gained specific geographic observations of the Brandywine Creek as a defensive position. Even then, the commander-in-chief did not possess enough knowledge of the terrain and the British intentions.

This is excellent. There are always new dots to connect!