On Tuesday afternoon, September 16, 1777—five days after the Battle of Brandywine—George Washington and most of his 11,000-member Continental army stood atop the South Valley Hills in Chester County, Pennsylvania, ill-prepared to repel the approach of 14,000 British, Hessians and Loyalists composing Sir William Howe’s Crown Forces. Aside from skirmishing on the flanks, a fierce, natural event turned this into the grand battle that never happened. It is referred to today as either the Battle of the Clouds, Battle of Goshen, Battle of White Horse (or Whitehorse) Tavern, as well as the Battle of Warren Tavern.[1]

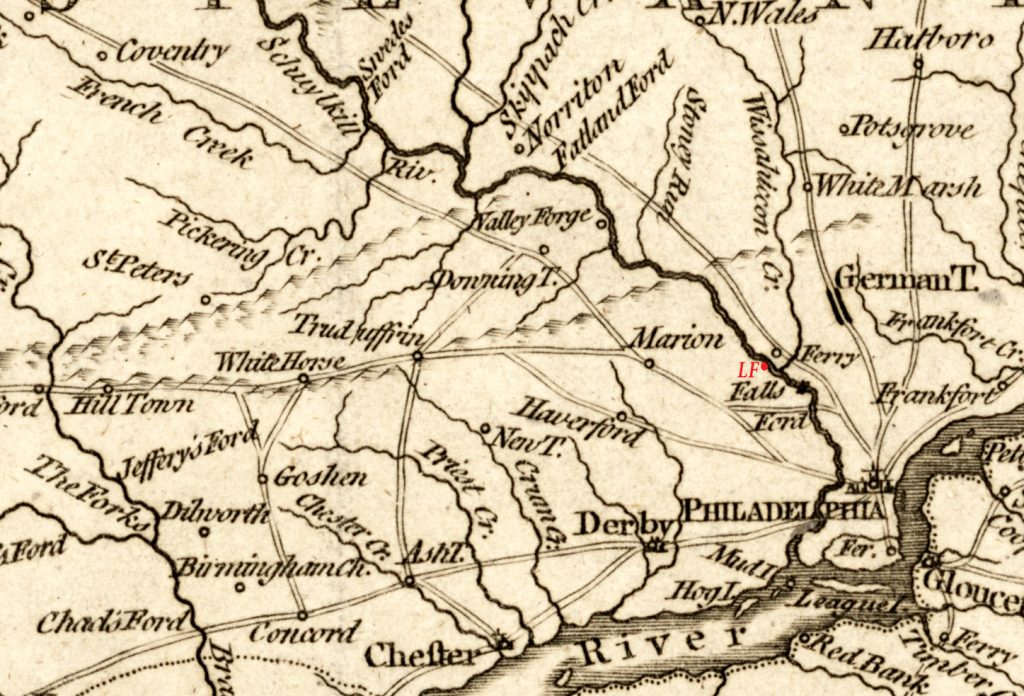

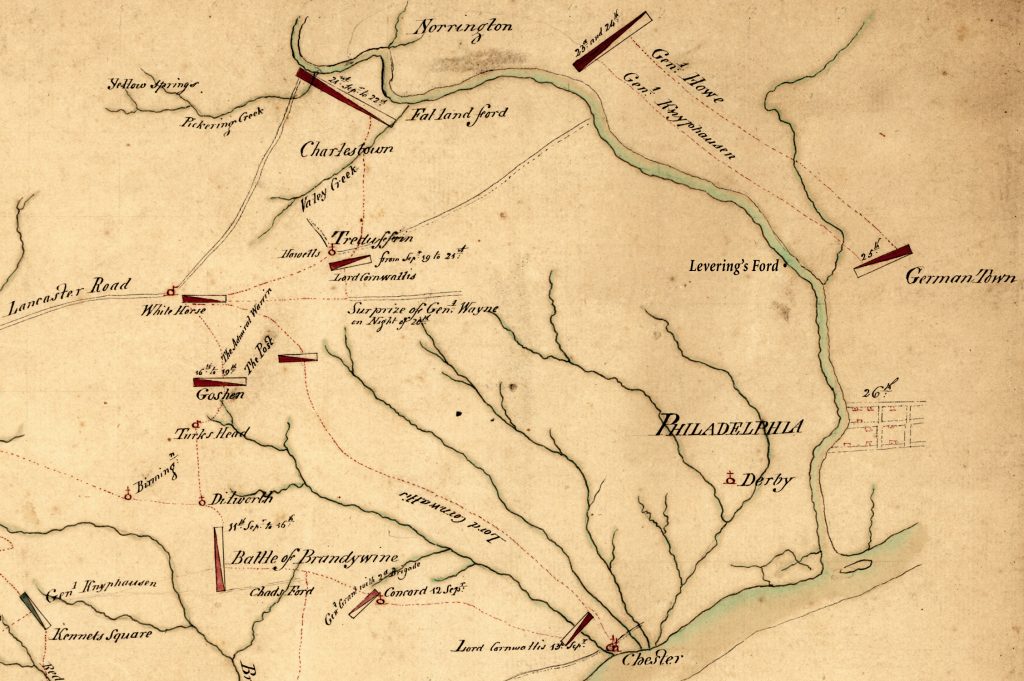

The chronology of this event is routinely depicted in histories devoted to the 1777 Philadelphia Campaign, along with the routes the opposing armies took from September 12 thru 16 to reach the battlefield. In short: General Howe remained at the southeast corner of the Brandywine battlefield with at least half of his army for five nights before moving northward on September 16. The other portion of his force, ultimately led by Gen. Charles Cornwallis, advanced to the outskirts of Chester on September 12 and 13 and remained in place until initiating a northward march during the evening of September 15. Meanwhile, George Washington and his Continental army retreated to Chester immediately after Brandywine and marched from Chester on the morning of September 12 eastward to the Schuylkill River opposite Philadelphia, which they completely crossed by early September 13. They immediately marched northward out of Philadelphia, encamped just south of Germantown for less than a day, and then headed west across a ford eight miles above Philadelphia. Throughout the rest of September 14 and all of September 15, the Continental army advanced more than twenty-five miles westward from Philadelphia on the Lancaster Road. On the morning of September 16, skirmishing on the heights south of the road prompted both armies to advance to those heights, the scene of the Battle of the Clouds.

The above synopsis accurately explains the outlines of what happened from September 12-16, 1777. Yet a simple, thoughtful gaze at a troop movement map depicting those five calendar days reveals how odd those movements really were, inviting a series of questions involving Washington and Howe, all beginning with “Why?” Two important questions have never been answered (or apparently asked). Others have been speculated upon or only partially answered. The following analysis provides more complete answers to questions regarding the decisions that led to the September 12-16 movements, revealing Washington and Howe as two aggressively-minded gamblers, each of whom clearly understood the stakes involved with his respective wager.

Why did General Washington cross the Schuylkill River into Philadelphia on September 13 only to re-cross the river over a ford that led to the Lancaster Road just twenty-four hours later, when he could have accessed the Lancaster Road without crossing the river at all?

General Howe’s decisive victory at Brandywine on September 11, 1777, opened the door to Philadelphia. General Washington and his Continental army retreated ten miles to Chester that night. By 4:00 A.M. the next morning Washington’s force was on the move northeastward toward Philadelphia. Part of the army crossed the Schuylkill at the moveable Middle Ferry bridge that night, but most crossed the bridge on Saturday morning, September 13. Within a day, the bridge was pulled in to the east side of the river, denying access to potential enemy forays.[2] The army immediately marched northward out of Philadelphia, and encamped a mile south of Germantown. According to Washington, “We brought the army to this place to refresh them with convenience and security.”[3]

The rest and repose was short-lived. Beginning at 9 the following morning, the Continental army began to re-cross the Schuylkill. This swift, forward-and-back movement provided Washington no fathomable advantage, suggesting that it was not pre-planned. If Washington decided to access the Lancaster Road on September 12, he could have simply followed the northward roads near the western bank of the river. This leads to the conclusion that Washington intended to stay on the Philadelphia side of the river for more than a day, but was induced to change his mind sometime late on Saturday, September 13; he issued orders for his army “to march tomorrow morning as soon as it is well light.”[4]

The demonstrated ignorance of a prominent official could have triggered Washington’s reversal. Thomas Wharton, the head of Pennsylvania’s state government, wrote a letter to Washington on September 12 and urged him to protect Philadelphia by sending troops to reinforce Swede’s Ford, which he believed Howe would attempt to cross to capture the city. This ford lay sixteen miles northwest of the city. “Below this pass,” Wharton noted, “there is no ford equally good or tolerably practicable.”[5] Washington most likely received this letter on September 13 while residing at the Henry Hill house one mile south of Germantown, the same quarters he occupied earlier in August. It was here during his summertime sojourn that Washington had likely learned of Levering’s Ford, less than two miles from the Hill property. Washington must have been struck that the head of Pennsylvania’s government felt knowledgeable enough to advise him about river crossings and yet was oblivious to Levering’s Ford’s viability.

Washington responded to Wharton that very day but never mentioned Levering’s Ford’s existence.[6] According to Gen. Peter Muhlenberg’s orderly book entry of September 14, the army broke camp under the belief they were heading to Swede’s Ford, a nine-mile northward march from camp.[7] Whether Washington decided that morning to use Levering’s Ford or purposely left the false impression to head to Swede’s to assure total security for his river crossing is unclear. Given that the army made a nonstop march to Levering’s indicates that Washington was certain the ford was viable (he may have had it confirmed by engineers earlier that morning). The answer to the next question will also provide evidence of why Washington appeared secretive about Levering’s Ford and why his army quickly distanced itself from it after passing it.

Why did Washington march westward on the Lancaster Road throughout September 14-15, distancing himself from Philadelphia without leaving any significant resistance at the fords and ferries closest to Philadelphia to block the British advance into the unprotected capital?

Based on subsequent events, it seems reasonable to assume that Washington moved his 11,000 troops toward Lancaster to prevent British troops from seizing military supplies at Reading. Washington, however, never mentioned this as a reason in seven known explanatory passages from correspondence written between September 13 and 23. Given that three of those passages were recorded while advancing to or from Reading, it would have been convenient for Washington for posterity’s sake to state that this was his objective. The fact that the supply depots were never mentioned is strong evidence that Reading was not a consideration for his movement.

Washington adamantly declared in all seven passages that he moved out on the Lancaster Road to battle Howe’s army. While encamped north of Philadelphia on September 13, Washington assured the head of Pennsylvania’s government that the best way to protect the city was “to oppose General Howe with our whole united Force.”[8] Just before he re-crossed the Schuylkill on Sunday morning, September 14, informed a confidant, “We . . . are just beginning our march to return towards the enemy.”[9] The next day, Washington revealed to John Hancock that “We are moving up this Road to get between the Enemy and the Swedes Ford & to prevent them from turning our right flank.”[10] He repeated the assumption that Howe was advancing toward the upper Schuylkill the following morning when he wrote Hancock, “am now so far advanced as to be in position to meet the Enemy on the Route to Swede’s Ford, if they should direct their course that way.”[11]

Washington wrote three times after the Battle of the Clouds explaining why he was at that locale, two of them exactly a week later. A council of war decided “That when the Army left Germantown upon the 15th instant it was with the determination to meet the Enemy and give them Battle whenever a convenient opportunity should be found.”[12] He wrote to Hancock the same day, “When I last recrossed the Schuylkill it was with a firm intent of giving the Enemy Battle wherever I should meet them.”[13]

The most revealing (and least cited) explanation was Washington’s September 19 letter to Congress. “When I left German Town with the Army,” he began to John Hancock, “I hoped, I should have had an Opportunity of attacking them either in Front or on their Flank with a prospect of success.”[14] Five days after being nearly decimated by Howe at Brandywine, Washington’s stated desire not just to engage Howe in battle but to attack him rather than defend served as a prelude to his mindset for the Battle of Germantown two weeks later. This was no Fabius.

Washington’s Great Gamble

Notable in these explanations is that while Washington’s mission was to battle General Howe, he not only expected that Howe’s primary objective was Philadelphia, but also that Howe was advancing toward Swede’s Ford as his avenue to the city. Was he certain Howe would take that route? One of Washington’s four explanations to John Hancock bears repeating, for it reveals that he was in the midst of a gamble: “am now so far advanced as to be in position to meet the Enemy on the Route to Swede’s Ford, if they should direct their course that way.”[15] That he wrote that letter on Tuesday morning, September 16, with nearly his entire army a full twenty-four miles from Philadelphia, emphasizes that gamble.

Washington had staked all on Howe believing that there was only one practicable route north from the British position near the Brandywine battlefield to cross Swede’s Ford (or other upper Schuylkill fords near it) and capture Philadelphia. Perhaps Howe’s stagnancy since the close of the Battle of Brandywine fortified Washington’s prediction. Washington’s gamble was that Howe had no knowledge of the Americans’ single-day sojourn east of the Schuylkill and his use of two different river passages that brought him over and back so quickly. The military moveable bridge had been safely pulled onto the Philadelphia bank of the river and Pennsylvania militia had been stationed at the site to prevent any elaborate attempts by the British to cross at the Middle Ferry—if Howe even knew that ferry existed.

The greatest part of Washington’s gamble was that he had waged everything on Howe’s complete ignorance of the existence of Levering’s Ford. It would have been a logical for Washington to deduce that if Thomas Wharton was unaware of it, than Howe must also be oblivious to it. The fact that Philadelphia was at least twelve road miles closer to the British at Dilworth Tavern by marching to Levering’s Ford than to Swede’s Ford magnified the stakes Washington had waged. Intensifying the gamble even more was Washington’s two-day march from Philadelphia at the time he told Hancock in writing of his readiness to battle Howe by blocking the route to Swede’s Ford “if they should direct their course that way,” thus admitting that Howe might direct his course another way—such as due eastward to Philadelphia. Washington’s tagged-on phrase must have caused Hancock some discomfort if he realized that Washington’s force was too far from the capital to save the city (and the Continental Congress) should someone on Howe’s staff or an area Loyalist with knowledge of the Schuylkill River notify the British commander of the open route to his objective.

One member of Washington’s army definitely understood the stakes. As the Americans continued their westward trek on the Lancaster Road on September 15, beginning the day already fourteen miles from Philadelphia, Gen. Anthony Wayne wrote to Thomas Mifflin, asking if Howe might “steal a March and pass the fords in the Vicinity of the Falls [of the Schuylkill] unless we immediately March down and Give them Battle?”[16]

Washington never wrote of any concern about Howe entering Philadelphia by a crossing at Levering’s Ford, but his actions throughout September 15 certainly suggested it. While his army slowly marched westward on the Lancaster Road, the commanding general stayed in the rear for most of the daylight hours that Monday. He and his staff retrograded eastward for part of the day, likely to make certain that no British forces were in the region to monitor his movement or to scout out river crossings. He dictated a letter to Congress through his aide, Robert Harrison, while still in the rear at 3:00 P.M., an unusual place for Washington to be compared to previous daylong marches.[17]

By the end of that Monday the vanguard of the Continental army reached White Horse Tavern and the rear stopped five miles from there at Paoli. The rear closed up two miles closer to the vanguard at Warren Tavern as Washington headquartered at a home in the middle of his line. By this time he had fielded an intelligence report that three spies had infiltrated British lines and learned that Howe believed part of Washington’s army was in Philadelphia and part was at Swede’s Ford. That the intelligence did not mention Levering’s Ford and that Howe had barely budged since the Battle of Brandywine may have placated Washington that Howe was more likely to be drawn toward Swede’s Ford than more directly to Philadelphia by way of Levering’s Ford.[18]

Why did Howe and over half of his army stay on the Brandywine battlefield for five nights after the contest and the remaining significant detachment tarry near Chester for most of this time, the latter a mere fifteen road miles from the Schuylkill River?

Philadelphia Campaign historiography provides several attempts to answer this question. Howe personally chose to stay tethered to the Brandywine battlefield with most of his force for over eighty hours after the close of the battle. He ordered a delayed pursuit down the road to Chester with two brigades under Gen. James Grant on September 12, followed the next day by General Cornwallis leading grenadiers and light infantry While Howe at the southern portion of the Brandywine battlefield, upwards of 5,000 infantry remained just a few miles northwest of Chester throughout Sunday, September 14.[19] “Howe’s delay eludes us,” admitted one modern campaign chronologist whose sentiments were shared by many others when he concluded, “and we must fall back on the quite valid observation that Sir William was rarely a general to be quick off the mark.”[20]

Although that assessment appears valid for Howe’s actions in 1776, extraneous factors came into play during the last days of summer in 1777. As recounted in several accounts of the campaign, Howe had several valid reasons to preside over an immobile army after September 11, at least for the two days. It may have been the simple combination of resting weary troops who had suffered more than 500 casualties, removing the wounded and interring the dead, as well as procuring supplies from their initial landing place at Head of Elk, Maryland, thirty miles away. Additionally, Howe initiated a successful and bloodless effort to capture Wilmington and establish it as a base to transfer supplies from Head of Elk, much closer to his army and Philadelphia. He transferred wounded to Wilmington on September 14.[21]

Howe not pursuing Washington, contrary to oft-cited opinions, likely had little impact on the Americans. Washington’s army had evacuated Chester beginning the morning after the battle, marching ten miles at a reasonable pace to reach Derby (now renamed Darby), a crossroads town five miles east of the Schuylkill, within a few hours. These movements prevented any reasonable chance for Howe to inflict significant damage to the Continental force by a direct pursuit by way of Chester, and also made it unlikely that Howe could have cut off Washington’s retreat toward Philadelphia by reaching the crossroads at Derby before him. It appears that Washington remained at or near Derby the rest of the daylight hours of Friday (the 12th) before moving eastward to the Schuylkill. Any significant threat to Washington that day was likely to induce the Americans to remain on the western side of the Schuylkill where they had access to the northern roads away from Philadelphia without being trapped at river’s edge. Given Washington’s history of elusiveness in the face of British pursuit in 1776, even a vigorous pursuit in the immediate aftermath of Brandywine was unlikely to injure the Continental army.

The stagnancy of Howe’s army during the entire daylight hours of September 15 bears investigation. By this time he believed that a portion of the American army had entered and stayed in Philadelphia while a significant detachment had moved sixteen miles north of the city to protect Swede’s Ford, perhaps the most reliable crossing of the Schuylkill River.[22] Many eastern Pennsylvania roads filtered into the Swede’s Ford road, including two northbound roads very near and easily accessible to each detached wing of Howe’s force. The ford was nearly twenty-five road miles northwest of Howe’s headquarters and thirty road miles from Cornwallis. Once across it, a very good road led into Philadelphia, but it required a sixteen-mile trek to enter the city. Thus, the route to Philadelphia via Swedes Ford would take three days from Brandywine, and a similar time for Cornwallis, if they could march unopposed for fifteen miles each day to enter the city.

Swede’s Ford appears utterly pointless as an option for Cornwallis, who stood only eighteen road miles to Philadelphia at Aston (near Chester) as well as for Howe who could reach Philadelphia in half the distance and time compared to the Swede’s Ford route if he continued eastward from Dilworth. Several fords and ferries of the Schuylkill existed within eight miles of Philadelphia. Certainly Howe realized by the morning of September 15 that if his intelligence was correct and Washington did indeed have part of his army east of the Schuylkill, then the Americans had crossed the river to the Philadelphia side without heading up to Swede’s Ford.

Surprisingly, no evidence exists that from September 12 to 15 General Howe made any attempt to sniff out the potential Schuylkill River crossings closer to Philadelphia. His chief engineer, Capt. John Montresor, created a map of fifteen fords of the Schuylkill, including four of them between Swede’s Ford and Philadelphia. One of them (Robin Hood ford) was the only one described as a “bad ford,” suggesting that the others were deemed crossable. The date of Montressor’s map is unknown; he could have created it later in the campaign. Given that a few passable fords were missing from his map suggests that Montresor drew this for Howe before the British occupation of Philadelphia.[23]

Whether or not he had possession of this map in mid-September, Howe’s decision not to perform a reconnaissance any closer to Philadelphia than Chester—just fifteen miles from the capital—strongly suggests that Philadelphia was no longer the chief objective of Howe’s campaign. Certainty of this can be found in Montresor’s journal entry for September 15:

The Commander in Chief went with his escort only of Dragoons to Lord Cornwallis’ Post 3/4 of a mile west of Chester. At 4 o’clock P. M. learnt that the rebel army which had crossed the Schuylkill at Philadelphia had repassed it to this side of Levering’s Ford and were pursuing the road to Lancaster.[24]

The source of this intelligence has never been identified, but it was most likely from a Loyalist or a small scouting party. Unknown from this passage is if Howe received the intelligence while he was visiting Cornwallis at Chester and then relayed it to Montresor at 4:00 P.M. after he returned to Dilworth (up to ninety minutes of one-way horse travel), or if both men were informed at the same time by the same unknown source. Regardless, Montresor’s passage is rich in its revelations and implications. Not only had Howe “learnt” of Washington’s movements of September 14 more than twenty-four hours later, the details about the Continental army’s location over the past three days strongly suggest that Howe had no idea that Washington’s army had been in and out of Philadelphia on September 13-14 until the afternoon of September 15.

Most importantly, Montresor identifies Levering’s Ford, thus confirming that he and certainly Howe both had become aware of this ford and its general location. By noting that Washington’s army had used the ford to cross the Schuylkill, Montresor and Howe obviously understood that Levering’s Ford was as clear and as safe a passage for an army to enter Philadelphia as it was for an army to depart from it. The fact that Montresor identified the crossing point by its proper name and without any further description of it suggests that Levering’s Ford and its location were already known to British high command, providing evidence that Montresor’s map of the fords was created prior to September 15.

Regardless if he knew of it beforehand or not, at 4:00 P.M. on September 15, 1777, Levering’s Ford was the ideal ford for Howe to use if his chief objective was to capture Philadelphia. When Howe visited Cornwallis less than a mile west of Chester on September 15, he stood a mere eighteen uncontested road miles from that ford and once across it, only eight more road miles from the center of the rebel capital. The rest of Howe’s men closer to the Brandywine battlefield were eight miles northwest from Cornwallis, but a fairly straight road network placed him only three more miles from Levering’s Ford than Cornwallis, as little as one extra hour to march to it.

Most of the Philadelphia Campaign literature misidentifies Swede’s Ford as the most desired and practicable Schuylkill crossing for Howe’s entry into Philadelphia event though it was a longer route to the city than Levering’s Ford. The most important difference between the two fords on September 15 was that the route to Levering’s Ford, and the ford itself, was virtually uncontested for both portions of Howe’s separated forces. By contrast the converging routes to Swede’s Ford for both wings of Howe’s army were blocked by an armed and game Continental army. Furthermore, the British high command was under the impression that behind Washington’s army, Swede’s Ford was also defended by American troops and artillery.

Howe’s Great Gamble

Howe had invested a great amount of time, effort and money to conduct his Philadelphia Campaign. He had departed New York with men and materiel on a fleet of over 250 ships on July 23 to sweep into Philadelphia from the Delaware Bay. Blocked by Washington’s forts for the quickest waterway access, he committed his army to the Head of Elk where he had landed on August 25. Just three weeks later, at 4:00 P.M. on September 15, he learned he had been given a wonderful gift from George Washington. Not only could he enter Philadelphia as early as September 16, he could do so unopposed.

But Howe did not choose that plan. Reacting to the newly received intelligence regarding Washington’s location, Howe ordered Cornwallis to march northward toward the Lancaster Road (Cornwallis began his movement at 8:00 P.M.). Howe and the rest of his army commenced their march early the next morning “towards Lancaster by the way of the Turk’s head.”[25] General Howe had shunned the path of least resistance to Levering’s Ford; he also provided no orders to go to Swede’s Ford. His new endpoint was the Lancaster Road—where he believed he would find General Washington and his army.

Montresor’s September 15 journal entry provides absolute proof that Howe changed the prime objective of his campaign from Philadelphia to the Continental army. This was an obvious and abrupt new mission that clearly did not carry the same priority at the start of the campaign. If Howe’s focus had been Washington first, Philadelphia second during the spring or early summer, he would have continued his attempts—frustrating to him as they had been throughout the spring season—to lure Washington from the protection of the New Jersey’s Watchung Mountains and goad him into open-field battle rather than take a huge armada to the opposite side of Philadelphia during burning hot summer weeks.

The capture and occupation of Philadelphia remained Howe’s chief objective from the day he departed Head of Elk and throughout the first ten days of September. Howe generally avoided confrontation with Washington when the Americans ensconced on the heights behind Red Clay Creek in Delaware at the end of September’s first week, choosing to skirt around the American right flank rather than feign in front of the position, cross the creek above Washington’s flank and attack him there, near Stanton, much like he did at Chadd’s Ford on the Brandywine a few days later.

Washington and the Continentals became Howe’s primary objective—even over the capture of Philadelphia—as early as the evening of September 11, but no later than the afternoon of September 15. It appears that the Battle of Brandywine was an unsatisfactory victory to him. Howe sacrificed a guaranteed swift and bloodless entry into Philadelphia via Levering’s Ford in order to have another attempt at crippling or destroying Washington’s Continental army in an open-field fight, one that would likely cost the British precious time and valuable casualties. That is the apparent premium he placed on advancing northward toward his opponent rather than eastward unopposed into Philadelphia.

The twin gambles waged by opposing commanders delayed the capture of Philadelphia by ten days. With the help of torrential rains on September 16, Washington escaped what could have been his most disastrous defeat of the war, resupplied his army by moving northwest from White Horse Tavern and further away from Philadelphia. High waters in the upper Schuylkill, rearguard harassment by a detachment of Continentals, and the sudden re-appearance of Washington with the bulk of his army on the opposite shore of the river, slowed Howe’s crossing until September 23, when he slipped by Washington’s left flank, crossed a ford five miles above Swede’s Ford, and marched into Philadelphia three days later.

What did this ten-day delay cost Howe? Although he suffered no appreciable casualties between September 16 and 26 while inflicting at least 250 losses upon the Continentals at the Battle of the Clouds and at Paoli, Howe may have lost a grand opportunity to surprise and capture some members of the Continental Congress. John Adams’ diary entries from Philadelphia are telling. On September 16 he pointed out that no newspapers were available, the city was quiet, and he believed that Howe was still fifteen miles away. Furthermore, Adams noted that the first members of Congress departed on September 19.[26] Howe merely needed to place a token force at Middle Ferry and at Levering’s Ford on the morning of September 16 to have cut off the western and northern escape routes out of Philadelphia. The deluge that emptied from the skies over the next eighteen hours of that Tuesday and the following day was severe enough to impede Delaware River crossings.

Even if every member of Congress had escaped him, Howe’s capture of Philadelphia on September 16 more certainly would have seriously damaged his opponent’s reputation in the collective minds of America. Washington’s gamble would have failed, with Howe’s army slipping in behind him over Levering’s Ford just two days after Washington departed it and distanced himself too far from it to return in time. Not only would Washington have been forced to explain how he could give up the capital city without any resistance, he would have to struggle to provide a reason why his movement away from the city at the same time Howe entered it was anything less than fleeing in the face of danger. This unfortunate incident would have fueled a much greater level of dissent against Washington than what was contained within the elements of the Conway Cabal that sprung from this campaign, particularly when juxtaposed against Horatio Gates’s victory at Saratoga one month later.

Howe’s first written words of these five days provides evidence that his failed gamble on September 15 and subsequent fruitless pursuit of George Washington was injurious to him. Washington’s uncanny ability to escape Howe’s clutches made him more than a thorn in the British side, as the 535 casualties inflicted by Washington’s surprise attack at Germantown on October 4. Six days after the bloodshed at Germantown, General Howe chronicled the campaign nearly daily from the Head of Elk through the October 4 battle and submitted the report to Parliament. He wrote nothing about September 15, the day he clearly chose to prioritize the destruction of Washington’s army over the capture of Philadelphia. Howe’s entry for September 16 changed the actual history of the campaign to make it appear everything he learned about Washington’s whereabouts occurred while already advancing to Swede’s Ford:

The Army moved in two columns toward Goshen on the 16th; and intelligence being received upon the march, that the enemy was advancing upon the Lancaster Road, and were within five miles of Goshen, it was immediately determined to push forward the two columns, and attack them.[27]

Did General Howe forget the true chronology of his September 15-16 movement less than four weeks later when he penned the report? This is doubtful. Howe had deliberately chosen to conceal the actual turn of events—that he and Washington raised the stakes against each other from September 12 to 16, 1777, a wager that Washington won and he had lost.

A dozen days after submitting his report, complete with the above disingenuous chronology, General Howe wrote to Parliament again—this time to submit his resignation.

[1]Chester County Planning Commission, “Campaign of 1777: Battle of the Clouds,” www.chescoplanning.org/HisResources/BattleClouds.cfm.

[2]General Orders, September 12, 1777, in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 11 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 204-205 (PGW); James McMichael Diary, September 12-13, 1777, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (16), 150 (PMHB); “The Military Journal of George Ewing,” in: Thomas Ewing, George Ewing, Gentleman, a Soldier of Valley Forge (New York, 1928). 22-23; George Washington to John Armstrong, September 14, 1777, PGW, 224.

[3]Washington to William Heath, September 14, 177, PGW, 227.

[4]General Orders, September 14 [13], 1777 PGW, 223.

[5]Washington to Thomas Wharton, September 13, 1777, PGW, 222. Although Wharton’s official title was “President of the Supreme Executive Council of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” he was more akin to the governor of the state.

[6]Washington to Wharton, September 13, 1777, PGW, 222.

[7]General Orders, September 14 [13], 1777 PGW, 223.

[8]Washington to Wharton, September 13, 1777, PGW, 222.

[9]Washington to Heath, September 14, 177, PGW, 227.

[10]Washington to John Hancock, September 15, 1777, PGW, 236-37.

[11]Washington to Hancock, September 16, 1777, PGW, 247.

[12]Council of War, September 23, 1777, PGW, 294-296.

[13]Washington to Hancock, September 23, 1777, PGW, 301.

[14]Washington to Hancock, September 19, 177, PGW, 268

[15]Washington to Hancock, September 16, 1777, PGW, 247.

[16]General Orders, September 14 [13], 1777, PGW, 223; Anthony Wayne to Thomas Mifflin, September 15, 1777, Anthony Wayne Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Wayne’s description singled out Levering’s Ford.

[17]Washington to Hancock, September 15 and 23, 1777, PGW, 236-37, 301. Also see annotations on page 233.

[18]John H. Hawkins Journal 1779-1782. MS Am. 0765 (Old Manuscript Guide 273), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; John Heard to Washington, September 15, 1777, PGW, 240.

[19]Howe to Lord George Germain, October 10, 177, published in the Pennsylvania Ledger, March 4, 1778. Howe has been traditionally criticized for not aggressively pursuing Washington on September 12. Washington’s rapid departure from Chester at 4:00 A.M. to Philadelphia would have rendered fruitless a most vigorous pursuit.

[20]John Buchanan, The Road to Valley Forge: How Washington Built the Army That Won the Revolution (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004), 254.

[22]Howe to Germain, October 10, 1777, published in the London Gazette, December 2, 1777 and republished in the Pennsylvania Ledger, March 4, 1778; Heard to Washington, September 15, 1777, PGW, 240.

[23]“Fords Across the Schuylkill River in 1777 From Potts Grove to Philadelphia,” in G. D. Scull, “The Montresor Journals,” Collections of the New York Historical Society, vol. 14 (1881), 419. For the identification of other fords not placed on Montresor’s map, see Charles R. Baker, “The Stony Part of the Schuylkill: Its Navigation, Fisheries, Fords and Ferries,” PMHB 50 (1926): 344-366.

[24]“The Montresor Journals,” 452.

[26]John Adams diary, September 16-19, 1777, www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=D28&bc=%2Fdigitaladams%2Farchive%2Fbrowse%2Fdiaries_by_number.php

[27]Howe to Germain, October 10, 1777, published in the London Gazette, December 2, 1777 and republished in the Pennsylvania Ledger, March 4, 1778.

5 Comments

“Howe sacrificed a guaranteed swift and bloodless entry into Philadelphia via Levering’s Ford in order to have another attempt at crippling or destroying Washington’s Continental army in an open-field fight,”

One does not attempt a river crossing when an enemy army is sitting on your flank. Crossing Levering’s Ford as you suggest would have found Howe’s army at some point half on the north bank of the Schuylkill and half on the south bank (or in various portions), troops on either bank unable to support the other. Washington would have been able to anticipate this and strike at a most inopportune moment. Howe would have required the better part of a day to get his troops and baggage across, and during this entire time he would have been vulnerable. Thus he had to drive Washington’s men further into the hinterland to buy the time to make this crossing. Washington, bringing his army into the Great Valley along the Swedeford road afforded just this opportunity.

Howe sat his army immobile for five days after Brandywine because he was shortening his line of communications some 30 miles by shifting his depot from Elkton to Wilmington, his supply ships transiting from the Chesapeake to the Delaware Bay to affect this. He had to wait. This LoC had to be shortened because the further he went from his ships the more vulnerable it became to raids; etc. (Note the reason Washington had Wayne ensconce his troops in the woods around Paoli tavern… to get at the British baggage column once their main force had marched passed. Reconstituting a destroyed baggage column would have cost Howe a week at least.) Howe fought this campaign in stages, methodically… this passage of the fleet from the one body of water to the other marking the transitioning to the next stage of the campaign. One can discern Howe’s methodology by looking at the New York campaign the year before; similarly fought in stages.

Getting your army on the flank of the enemy was a bit like getting the weather gauge in the naval parlance of the era. Howe’s and Washington’s “chess” moves in this early part of the campaign were all about this. Howe turning Washington out of his position on the Red Clay Creek, then again on his flank march at Brandywine… both intended to put the unfordable Delaware River at Washington’s back. Then Washington occupying South Valley ridge preventing Howe the attempt at crossing of the Schuylkill while at the same time denying him the Swedeford Road.

In addition to Ed’s “Stirling Bridge” scenario posited above, another explanation for Washington’s Continentals not guarding Levering’s Ford is that Armstrong’s PA militia had been given the task.

In “Campaign to Valley Forge” John F. Reed states: “…Washington ordered Armstrong’ militia “to throw up redoubts at the different fords” as far up the river as Swede’s, at the present Norristown.” (pps. 146-7) This tasking would therefore encompass covering the crossing at Levering’s.

It would not have been impossible for Howe to launch his troops into the swift flowing, waist-deep waters of the Schuylkill river. It was just unlikely he’d do so, especially when that crossing would have been opposed, if only by militia, and his army might have been attacked and mauled piecemeal by Washington.

Stirling Bridge? Good. Except that in this case Wallace’s force was on the same side of the river, just beyond a hill or two, and just waiting for Howe to start crossing the ford. Good point about Armstrong’s militia. Imagine Wallace’s force then in two parts, the weaker portion on the opposite bank baiting Howe to make the attempt.

Excellent points, gentlemen.

It seems to me Armstrong had too few men to cover too many areas that day. No evidence has turned up that any of Armstrong’s militia was posted at Levering’s Ford. There were more than eight viable fords up the Schuylkill from Middle Ferry; if the Pa. militia had men at every possible crossing, it would have been a very weak resistance at most of those fords, particularly since we do know that Armstrong followed his orders and put more attention at Middle Ferry and Swede’s Ford, thus severely limiting his potential to cover the rest.

As for the claim that “One does not attempt a river crossing when an enemy army is sitting on your flank,” isn’t that exactly what Howe accomplished on September 23 at Fatland Ford, with Washington’s men less than five miles up the river bank from him? Washington had no Continentals closer than fourteen miles from Levering’s Ford on the morning of September 16. From the time the intelligence about British presence at the ford has to travel that distance to reach Washington (over 1 hour), and then for Washington to react to it as soon as humanly possible and have his men redirected with orders to head back (30+ minutes), followed by his men marching three miles per hour to return to the ford (4+ hours), I envision no less than a 6-hour response time for Washington to return enough firepower to the ford to do something substantial.

This all makes me better appreciate Howe’s maneuvers on the upper Schuylkill with Washington’s left flank less than a 90-minute march from the British crossing point and the Continental army already on the Philadelphia side of the river when Howe successfully crossed on September 23. With a march twice the distance to the city than from Levering’s Ford, Howe was still able to enter the city three days later, fairly unopposed in front or rear.

Acknowledging that unlike the clandestine overnight passage through Fatland Ford, Howe would be crossing Levering’s Ford in broad daylight, it still needs to be asked why couldn’t Howe accomplish the same feat a week earlier at Levering’s Ford with Washington several hours away from him as he did on September 23 when Washington was less than a 90-minute march away from him at the start of the British crossing? I maintain that if Howe wanted to, he could with much less risk to his river passage. This pointedly shows that on September 15-16, Howe prioritized another “stab” at Washington over the easiest, safest route into Philadelphia.