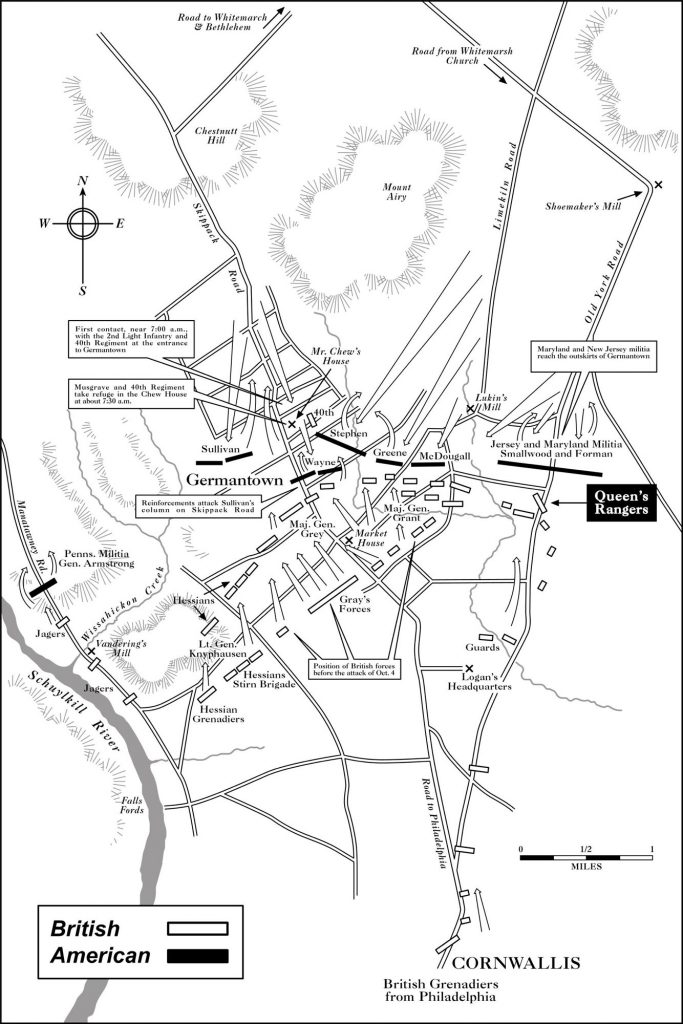

In the early hours of October 4, 1777, the Maryland militia trudged southward along the Old York Road in eastern Pennsylvania. In the distance off to their right, the rumble of cannon fire punctuated just how behind schedule they were. The battle in which the militiamen were to participate had begun, yet they were still far from their designated start point. Under the command of Brig. Gen. William Smallwood, the Marylanders (augmented by several hundred New Jersey militia under Brig. Gen. David Foreman) comprised the left-most pincer of a complex, four-pronged attack planned by Gen. George Washington to strike a portion of the British army posted at the hamlet of Germantown, Pennsylvania, just northwest of Philadelphia. Faced with a twenty-mile march, Smallwood’s column departed the American camp around 6:00 PM the evening of October 3, but the darkness of a moonless, overcast night combined with a lack of guides on unfamiliar roads to impede their progress.[1] The going was slow. A member of one of the flanking parties took a turn down the wrong road and was captured by British pickets. Now, as the battle was beginning, early morning mist coalesced into a thick fog. The officers urged the militiamen forward. Among these leaders was a lieutenant from Frederick, Maryland—Michael Grosh.

I first encountered Michael Grosh while doing research on the Maryland Line of the Continental army. Michael’s younger brother, Adam Grosh, was a captain in the 7th Maryland Regiment at the Battle of Germantown. Adam and Michael, along with their older brother Peter, all joined the Frederick County militia at the outbreak of the War for Independence. Adam went on to serve as a regular, first as a lieutenant in the Maryland Flying Camp, then remaining with the Maryland Line as an officer in the Continental army. He would resign as a major in 1780.

Capt. Adam Grosh survived the Battle of Germantown. Lt. Michael Grosh, of Baker Johnson’s battalion of the Maryland militia, did not. At the time of my research, I found this curious. The role of the militia under Smallwood is usually dismissed in accounts of the action at Germantown. The Smallwood column supposedly did not arrive in time to take part in the attack. So how was it that Michael, and not Adam, fell on October 4? Investigating this question requires a reexamination of the Maryland militia’s performance in the Philadelphia campaign leading up to Germantown.

That performance was mixed at best. The summer of 1777 saw all the nascent American states on alert, not knowing what the objective of the British army under Gen. Sir William Howe would be. All the leaders of Maryland could do, along with their contemporaries in sister states, was wait. At last news arrived. On August 17, an officer named Thomas Timson “came up from Virginia,” according to a circular letter from the Maryland Council of Safety, “and informed that on Thursday Evening last [August 14] he saw a Fleet of the Enemy’s Ships coming within the Capes.”[2] The British army, about 23,000 including troops, officers, servants, and camp-followers, all on an armada of 266 ships, were sailing up the Chesapeake Bay.[3] Maryland went into a panic. Thomas Johnson, governor of Maryland, called out the militia in an official proclamation on August 22, declaring that “This State [was] being now actually invaded by a formidable land and sea force.”[4] Turnout by the militia was confused and haphazard. General Smallwood and Col. Mordecai Gist, Maryland’s two most senior Continental officers, were dispatched by General Washington on August 23 to “repair to Maryland without loss of time for the purposes” of organizing the state’s militia in the face of General Howe’s offensive.[5] In a letter to Governor Johnson, Washington expressed his concerns about the disorganization of the state. The fact that Smallwood and Gist were needed “to arrange and command the Militia of Maryland,” Washington noted to Johnson, along with the “frequent applications” he had received “to send Officers to the Eastern Shore to take direction of the Militia assembling there,” gave the commander in chief “reason to believe, that the regulations, in this line, are not so good.”[6]

On Sunday, August 24, the Rev. Francis Asbury recorded that news of the British fleet moving up the bay “induced many people to quit Annapolis” for fear of Howe landing his forces. Fortunately for Annapolis, Howe’s objective was further north.[7] The British Army disembarked at Turkey Point, near Head of Elk, at the very top of the Chesapeake Bay, on August 25. Maryland’s militia was not there in force to oppose the landing. “The men were immediately formed by companies,” noted one of the Hessian auxiliaries to the British army, “but no enemy appeared.”[8]

There was some minor skirmishing between the British and Americans in the weeks following the British landing, but when Howe and Washington faced each in full force at Brandywine Creek on September 11, 1777, the Maryland militia was not present. Smallwood and Gist were still mobilizing the state’s forces, even while their own Continental units, the Maryland Brigade of John Sullivan’s Division, and the 3rd Maryland Regiment respectively, fought a desperate action at Birmingham Hill. When Maryland’s militia finally did march into Pennsylvania, they totaled about 2,100 strong.

Smallwood was attempting to rendezvous with Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne’s Continental division at Paoli Tavern on September 20, but about half of the Maryland force deserted in the face of the surprise night attack by the British under Gen. Charles “No Flint” Grey. After Paoli, the remainder of the Maryland militia linked up at last with the main body of the Continental Army at Pennypacker’s Mill around September 26, as noted by Capt. William Beatty of the 7th Maryland Regiment.[9]

It was this contingent of the Maryland militia, now about 1,100 troops, that Smallwood led on October 3-4 from Pennypacker’s Mill, accompanied by approximately 400 New Jersey militia, on a long, circuitous route toward Germantown. “Smallwood and Forman,” read the official October 3 General Orders for Attacking Germantown, “to pass down the road by a mill formerly Danl Morris’ and Jacob Edges mill into the White marsh road at the Sandy run: thence to white marsh Church, where take the left-hand road, which leads to Jenkin’s tavern on the old york road, below Armitages, beyond the seven mile stone half a mile from which [a road] turns off short to the right hand, fenced on both sides, which leads through the enemy’s incampment to German town market house.”[10]

The battle began at day-break, sometime around 5:00 AM. Washington’s plan called for four columns to converge on Germantown simultaneously: the far right column consisting of Pennsylvania Militia was under Gen. John Armstrong; Continental regulars under Gen. John Sullivan were in the center-right column; Continentals under Gen. Nathanael Greene made up the center-left column; and as noted above, Smallwood and Forman comprised the far left column.

Sullivan initiated contact with the enemy near the prescribed time, the surprise of which enabled his force to drive the British back into Germantown from the Allen house past the Chew House, named Cliveden, into the main British encampment. Unfortunately for the Americans, the fortification of Cliveden and subsequent defense by part of the British 40th Regiment, combined with the communication breakdown caused by fog and smoke, stymied the momentum of the attack.

Armstrong never advanced past the Wissahickon Creek. However, his presence on the British left flank was enough to keep the Hessian units occupied and out of the fight, which was a success in and of itself.

Both Greene’s column (the center left of the American attack) and Smallwood’s column (the far left of the attack) were slowed by the darkness and the confusing routes during the night march. Greene, according to John Sullivan, was even “oblidged to Countermarch one of his Divisions before he could begin the attack” because he found the British were arranged “in a Situation very Different from what we had been Told.”[11] All this delay resulted in Greene’s column of Continental regulars not entering the action until “three Quarters of an Hour” (according to Washington) to “near an Hour & a Quarter” (according to Sullivan) after the battle began.[12] The Maryland militia were even later. Lt. James McMichael of the Pennsylvania State Regiment, part of Greene’s column, records that his regiment was exposed on the left due to “the Maryland militia under the command of Gen. Smallwood, not coming to flank us in proper time.”[13]

Arriving sometime, therefore, between Greene’s column engaging the enemy and the American retreat in the face of the British counterattack, the Marylanders under Smallwood (and New Jersey militia under Forman) have generally been written off in most accounts of the Battle of Germantown. In his own writing of the battle after the action, Washington makes scant reference to the Smallwood column. Local historian Alfred Lambdin, in an address observing the 100th anniversary of the battle, noted that “Smallwood only came up toward the close of the action, in time to join the retreat. His movements, therefore, will not concern us.”[14] John Ferling, in Almost a Miracle, writes, “The Maryland and New Jersey militia never found Germantown.”[15] Robert Middlekauff, in The Glorious Cause, somewhat more generously observes, “Smallwood arrived much too late to exert pressure on the rear of the British, and retired almost as soon as he arrived.”[16] Christopher Ward, in is multivolume The War of the Revolution, asks rhetorically, “what of . . . the militia from Maryland and New Jersey—the jaws of the pincers, the claws of the crab?” He provides his own answer: when Smallwood’s force arrived, “it was too late for it to do anything but join the retreat.”[17]

Hence my curiosity as to how Michael Grosh, a militia lieutenant with Smallwood’s column, perished in the battle, rather than his brother Adam, an officer in the Continental army under Sullivan, who was in the thick of the action. Was Michael Grosh killed in the chaos of the retreat? Not likely. Sullivan characterized it as “a Safe retreat Though not a regular one,” and Smallwood reported to the governor of Maryland, “The retreat was prosecuted with little or no other loss, than the field of action.”[18]

That there was a “field of action” is a key element missed by the historians mentioned above. It suggests that the militia in Smallwood’s column did do more than just “join the retreat.” They engaged with the enemy. Two historians have, in fact, presented evidence to this effect. Patrick O’Donnell, in Washington’s Immortals, notes that, the “militiamen faced off with the elite of the British army: the Loyalist Queen’s Rangers and the light infantry and grenadiers of the Guards Regiment.”[19] Those participants of the battle who O’Donnell quotes attest to the engagement. Asher Holmes, for instance, was a New Jersey militiaman serving with General Forman “and the Maryland militia . . . under Gen. Smallwood.” Holmes confirms not only that their column was “on the left wing of the whole army,” but also, upon arriving on the battlefield, “drove the enemy, when we first made the attack, but by the thickness of the fog, the enemy got in our rear.”[20] Mordecai Gist, the senior Maryland colonel under Smallwood, recounted, “A few Minutes after this attack began, our Division under General Smallwood Fell in with their [the British] right flank, and drove them from several redoubts.”[21]

Historian Thomas J. McGuire, who has perhaps provided the most thorough examination of the Battle of Germantown (and the 1777 Philadelphia campaign as a whole), explains that the Queens Rangers and the Guards “had erected some earthworks, probably fleches, along the [Old York] road.”[22] The Marylanders stormed these British defenses, taking the small redoubt. To illustrate this action McGuire employs the tragic experience of Capt. James Cox, commander of the Baltimore Mechanical Company. He cites George Welsh, who wrote to Cox’s wife three days after the battle:

Dear Cousin, the disagreeable task is devolved on me, to let you know (though doubtless the news will reach you before this will come to hand), that your loving husband, and America’s best friend, on the fourth instant, near Germantown, nobly defending his country’s cause, having repulsed the enemy, driving them from their breastworks, received a ball through his body, by which he expired in about three-quarters of an hour afterwards.[23]

Just as Colonel Gist reported, the Marylanders not only attacked the British, they also drove the enemy from “several redoubts” (Gist’s term) or “their breastworks” (Welsh’s term) before the tide turned against them. Captain Cox, one of the leaders of this attack, was regarded highly enough for General Smallwood to report to Governor Johnson:

Captain Cox, of Baltimore, a brave and valuable officer, with Lieut. Crost, of Johnson’s regiment, and several other brave officers and men, were killed within twenty paces of the enemy’s lodgement before they were dispossessed of it.[24]

That second officer Smallwood identifies by name, “Lieut. Crost, of Johnson’s regiment,” appears to be the Lt. Michael Grosh of our small mystery. No “Crost” appears on the muster rolls or pension records for Maryland. “Michael Grosh,” however, does appear as a second lieutenant in Capt. John Haass’s company on the muster roll of Frederick County, November 29, 1775.[25] And we do know Michael Grosh died at Germantown. In 1778, Peter Grosh went before the Frederick County Orphan’s Court on behalf of his widowed sister-in-law to apply for a pension. The notes from the court state that a certificate from Lt. Christian Weaver set forth that “the said Michael Grosh was a Second Lieutenant under the command of Colonel Baker Johnson and met with his death at the Engagement at German Town.”[26] Michael’s wife, Chistianna, was granted a pension of £5 per month from October 18, 1777 thru October 18, 1778. About five years later, Michael Roemer, either Christianna’s father or brother, applied for further relief on behalf of Grosh’s two children. The orphan court granted £300. And finally, Michael’s father, Conrad, provided for the two children in his will in 1786.[27]

Of course, the death of Michael Grosh affected his family greatly. The first of Conrad and Maria Grosh’s children to be born in America, he was also the first of their children to die in America, and he left a widow with two young daughters. But for our purposes, the record of his death, along with the records of James Cox and other Marylanders who died storming the British defenses outside Germantown, help to illuminate the actions of the Maryland militia under William Smallwood’s command that day, which has often been written off by historians as having “arrived too late.” True, they were late. But the left pincer column did join the attack. After a lackluster start in late August and September, the militiamen performed their duty in battle on October 4. The American conduct at Germantown, even though a defeat, has been credited with convincing the French, “almost as much” as the victory at Saratoga, that the Americans were able to go toe-to-toe with the British army, and “would prove to be efficient allies.”[28] Given the significance of the battle, reassessing the action of the militia at Germantown is certainly warranted.

[1]General Orders for Attacking Germantown, 3 October, 1777, in The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (hereafter PGW), Philander Chase, et. al, editors (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001) 11: 375.

[2]Council to Lieutenants, Aug 18, 1777, Archives of Maryland, Volume 16, Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1, 1777 – March 28, 1778, 338, aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000016/html/am16–338.html.

[3]Michael C. Harris, Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia But Saved America, September 11, 1777 (El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie, 2014), 57.

[4]J. Thomas Scharff, Maryland: From the Earliest Period to the Present Day, vol. 2 (Baltimore: John B. Piet, 1879), 317.

[5]George Washington to William Smallwood, August 23, 1777, PGW, 11: 55.

[6]Washington to Thomas Johnson, September 3, 1777, PGW, 11: 137.

[7]Francis Asbury, Journal of Rev. Francis Asbury, Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, vol. 1 (New York, 1852), 254.

[8]Quoted in Harris, Brandywine, 112.

[9]William Beatty, “Journal of Captain William Beatty,” Maryland Historical Magazine, vol. III (Baltimore, 1908), 110.

[10]General Orders for Attacking Germantown, October 3, 1777, PGW, 11: 375.

[11]John Sullivan, Hammond, Sullivan Papers, 1: 542—47. Quoted in PGW, 11: 396.

[13]Lt. James McMichael, “McMichael’s Diary” 152-53, Quoted in PGW, 11: 397.

[14]Alfred C. Lambdin, “The Battle of Germantown,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 1, No. 4 (1877), 376.

[15]John Ferling, Almost a Miracle, The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 254.

[16]Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution , 1763-1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 401.

[17]Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution, vol. 2 (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952), 370.

[18]John Sullivan, Hammond, Sullivan Papers, 1: 542—47. Quoted in PGW, 11: 396. Smallwood to Johnson, The North American Review, Vol. 23 (1826), 435

[19]Patrick K. O’Donnell, Washington’s Immortals: The Untold Story of and Elite Regiment Who Changed the Course of the Revolution (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016), 159.

[20]Asher Holmes to his wife Sallie, October 6, 1777, in George C. Beekman, Early Dutch Settlers of Monmouth County, New Jersey (Freehold, NJ: Moreau Bros., 1901), 118.

[21]Mordecai Gist quoted in O’Donnell, Washington’s Immortals, 160.

[22]Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II: Germantown and the Roads to Valley Forge (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2007), 105.

[23]George Welsh to Mary Cox, October 7, 1777, cited in J. Thomas Scharff, The Chronicles of Baltimore: Being a Complete History of “Baltimore Town” and Baltimore City from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (Baltimore: Turnbull Brothers, 1874), 165-166.

[24]Scharff, The Chronicles of Baltimore, 166.

[25]Journal of the Committee of Observation of the Middle District of Frederick County, Maryland, September 12, 1775—October 24, 1776, Maryland Historical Magazine, 1916, vol. XI, No. 1, 53.

[26]Frederick County Register of Wills (Orphan’s Court Proceedings) Minutes and Proceedings, GM#1, ff. 11-12,

msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/014300/014384/pdf/minutebkp11-12.pdf.

[27]For sources on the Grosh Family, see Archives of Maryland (Bibliographic Series) MSA SC 3520-14384; MSA SC 3520-14385; MSA SC 3520-14386, msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/mdsoldiers/html/mdsoldiers.html.

[28]George O. Trevelyan, The American Revolution, in 6 Volumes., London, 1909—1914, cited in Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution, 371.

7 Comments

Good stuff. Thank you for digging into this.

Thank you!

Interesting find. Just playing Devil’s Advocate for a moment, given the less than stellar performance of the Maryland Militia on the night of Paoli, is it possible that Smallwood and Gist were tempted to “big up” their actions at Germantown (in much the same way that Simcoe did in his book about the service of the Queen’s Rangers)? Having read McGuire’s book on Paoli, I found it rather surprising that they should have been entrusted with such an important role at Germantown.

With Smallwood, it is possible for him to have embellished his role. Otho Holland Williams insinuates in his “Narrative of the Campaign of 1780” that Smallwood did as much after the Battle of Camden dictating “letters which he addressed to Congress” that resulted, “it was generally believed,” to have helped procure Smallwood’s promotion to Major General. Gist, however, is more reliable. Also, the number of claimants in Maryland’s pension records citing injury or death at Germantown, and who were in militia service, support the observations made by Smallwood and Gist. Digging into the New Jersey records for the men serving under Forman would help corroborate my assertion that the left wing did make contact with the enemy (or not).

Thanks for reading the article and for the comments.

Great article Mr. Lapp! My 6th GGfather was in this battle. Shot in the neck but non-lethal injury. All I have to go on are family and pension records, where he stated he enlisted in Fredericktown, Md, under captain Ralph Hillory in a flying camp for 18 months. Under this enlistment, he was at the Germantown Battle. And in the 18 months enlistment in the flying camp, his captain was Ralph Hillory. He says General Smallwood and Colonel Will Luckett was with them and many others that he has forgot (He was in his 80’s when this pnsion statement was given).

Well done Mr. Lapp! My 5th GGfather was also in this battle, CPT Wm Pepple (or Peppel, Pepples, or Pebble) in the 35th Battalion. All I have are scant pension accounts from men in his company who attest that they and then therefore my GGfather were there. Any details into the militia’s role at Germantown or his life is greatly appreciated!

I recently discovered this Journal. I am most impressed. The article on the death of Michael Grosh was great. Peter Grosh was my 4th GGfather. His brothers Michael and Adam were my 4th GG uncles. The article added some new information for me on Michael and Adam during the war. Mr. Lapp, thanks for your research into this personal hero.