Robert Erskine was born in Dumfermline, Scotland, to Ralph and Margaret Erskine on September 7, 1735. Ralph Erskine, being a Presbyterian minister, raised Robert to be thrifty, God-loving, determined, and well-educated. In 1748 and then again in 1752 he was enrolled in the University of Edinburgh. There are no records of his performance or if he even completed his studies. Upon leaving the university he moved to London and found employment that allowed him to get by. In 1759, he formed a business partnership with a Mr. Swinton selling hardware and farm tools. In 1760, hoping to do business in the American colonies, Swinton travelled to the Carolinas with a significant consignment of merchandise. Erskine never heard from him again and was forced to file for bankruptcy. Using his mechanical talent, he invented and patented a “Continual Stream Pump.” His plan was to use the profits from the sale of the pumps to payoff all of his creditors. Unfortunately, he needed £600 up front to market his invention—this forced him to abandon the plan. In June 1762, almost twenty of his creditors filed a grievance against him. He was detained by the London debtors’ court but soon freed on his own recognizance and a promise once back on his feet to settle his accounts.

In 1764 Erskine received a letter from the first company that might find his pump useful:

I hereby acknowledge to have received of Mr. Robert Erskine, inventor of a New machine for raising water, an account of the principles on which the said machine is founded and by which it operates, to send to the Directors of the Salt Works of Westphalia, for them to judge which [whether] such a machine will be proper for their use. Bert’d Rappard[1]

This eventually led to the manufacturing of the pump by William Cole, an instrument maker in London. During this time Erskine also honed his skills as a draftsman and invented the Platometer, an instrument used, “to find the latitude & variation of the needle at Sea any time of the day by two observations of the Sun & any time of the night by taking the altitude to two known fixed Stars at the same time.”[2]

In May 1765, Erskine demonstrated the superiority of his newest invention, the Centrifugal Hydraulic Engine, at Woolwich Dock in London; in January 1766, he gave another demonstration at Woolwich aboard HMS Princess Mary. He was then asked to design a pump for the two cisterns at Oxford Hospital that when full held sixteen tons of water; his pump was able to fill both cisterns in six hours. The pump proved to be thirty percent more efficient than any in use at the time. It was not long before he turned his skills to the efficient utilization and control of rivers for civic improvement.[3] He designed ways for increasing the fall in the River Colme in County Essex, published a manuscript entitled A Dissertation on Rivers and Tides, and an essay on the effects of bridges and abutments in rivers; he was also being considered for the City of London’s project to improve the Thames.

Near the end of 1769, Erskine was approached by a representative of the Hasenclever, Seton & Crofts Syndicate in London. The group had purchased four pig iron mines at Ringwood, Long Pond, Cortland, and Charlotteburg in Bergen and Morris Counties in New Jersey and in Rockland County in New York. The combined properties were named “The American Iron Company.” The company had built four furnaces, seven forges, one potash and pearl ash manufactory, 235 houses primarily for the workers, dams for thirteen mill ponds, ten bridges,[4] but due to mismanagement the mines were financially unsuccessful. Gov. William Franklin of New Jersey, on behalf of the syndicate, directed four men to evaluate the state and condition of the mines and furnaces and forwarded their findings to London.[5] One of the evaluators, a co-owner of the nearby Hibernia Mines, was William Alexander, otherwise known as “Lord” Stirling. During the winter of 1769-1770 the syndicate decided to approach Robert Erskine and offer him the position of Director of the American Iron Company. It is very likely they were aware of his “professional work in the neighborhood of London, his private commissions from various men of nobility, and his published communications to the newspapers regarding civic improvements.”[6]

Erskine accepted the position and spent the next two months travelling to the different mining regions of Britain. He learned the technical and mechanical details connected with mines and furnaces, the types of ore, the nature and properties of iron, the casting of iron, and the manner of converting iron into steel.[7] What made his commitment to his new job even more remarkable was early in 1771, his “Centrifugal Hydraulic Pump for raising water” was presented at the Royal Society of London. After reading his paper to the members and answering all of their questions, his invention was approved and he was granted a fellowship in the Society. If he had decided to remain in London and declined his new job offer, most people would have understood, but he had given his word and he was going to honor his commitment. The original certificate awarded to Erskine by the Society read , “A Gentleman well versed in Mathematics and Practical Mechanics.” Among the signatories of his certificate were Sir John Pringle, president of the society from 1772 to 1778, and Benjamin Franklin.[8]

Erskine set sail aboard the ship Britannia for America in April 1771; he arrived at New York City on June 5. He immediately visited each of the mines and on July 9 sent his first report to the syndicate. In it he pointed out the strengths and weaknesses of each site, described the improvements he was planning to make initially and expressed his first concern. “Your managers in future should I think act in Concert for the goods of the whole, without having separate Interests, and . . . if they agree in their plan of operations before hand, they certainly may diminish each others care greatly.”[9]

It did not take long before the foreman, John Jacob Faesch, and the New York City factors of the Syndicate began to look on Erskine as a troubleshooter from London and someone sent to spy on them. In the spring of 1772, Faesch decided to part ways with the American Iron Company. He bought his own mine and with its produce opened the modern-day equivalent of a hardware store. Erskine remained on amicable terms with Faesch and when needed, felt comfortable asking for his advice and/or assistance.

On March 24, 1773, Erskine was commissioned a Justice of the Peace; to his neighbors he was now an employer, a friend, and a law enforcement official.[10] As he reviewed the company’s record books during the year he realized that money had been wasted on unauthorized projects such as a saltpetre scheme, silver mines, tin mines, and wood cutting mills as well as loans granted to unknown people with no record of repayment. Unless additional capital was made available by the syndicate to re-establish the mines and furnaces, he believed that it could take up to ten years before the mines showed any profit.

In 1774 he began to file reports with the syndicate about the political sentiments in the colonies and their possible effects on the mines. In a letter dated June 1774, he wrote, “have no doubt that a total suspension of commerce to and from Great Britain will certainly take place. Such I know are the sentiments of those who even wished a chastisement to Boston”; on June 17, he wrote, “The Virginians . . . are the soul of America . . . but from what has appeared hitherto, the whole colonies seem to look on that of New England as a common cause”; and in October:

The Oliverian spirit in New England is effectually roused and diffuses over the whole Continent . . . a few drops of blood let run would make it break out in torrents which 40,000 men could not stem, much less the handful Gen. Gage has. . . . The ruler at home has gone too far. The Boston Port Bill would have been very difficult of digestion, but not allowing Charters, the due course of Justice, and the Canada bills, are emetics which cannot possibly be swallowed.

Erskine continued his warnings in early 1775:

The communication with my native country may soon be cut off. The prospect is very gloomy and awful . . .. The fate of the British Empire is likely to be rent to pieces . . . the generality of people at home are totally wrong in their ideas of this country . . . Perhaps the petition of Congress may afford a proper opening for a negotiation. Should that be rejected all hope of reconciliation will be cut off. That sword which has hitherto been drawn with reluctance will then be whet with rage, madness and despair.

In May he wrote, “The people are in earnest everywhere . . . Gen. Gage . . . could not stir ten miles had he 10,000 men; for 20,000 men who . . . are entrenched without the town . . . the situation of this country which is beyond dispute [is] indissolubly united against the British Ministry and their acts, to which the Americans will never subscribe.” And on June 23 he wrote, “The people of this continent . . . have their eyes about them and are determined to be free or die.”[11]

It is clear that Erskine believed Parliament was not aware of the intensity of the American colonists’ determination. Concerned that he might lose his workers to the army if a war broke out and for the safety of his workers’ families and the mines if the properties were raided, Erskine organized one of the first companies of militia in New Jersey from the men who worked for him. It was composed of “forgemen, carpenters, blacksmiths, and other hands.” In August 1775, the New Jersey legislature officially commissioned him as captain of the company. His men were outfitted and armed at Erskine’s own expense. On July 17, in New York City he bought fifty-seven guns and twenty bayonets; on July 19, he bought eighty yards of green coating and twenty-four pairs of shoes; and on October 10 three swords. His company varied in size from forty-five to seventy-five men. Drills were conducted at Ringwood and Long Pond.[12]On December 2, he sent a copy of his commission to the colonel of the 1st Battalion of Continental Troops of New Jersey. It read:

In Provincial Congress, Trenton, New Jersey, 17 August, 1775

This Congress being informed by John Fell, Esq., one of the Deputies for the County of Bergen, that Robert Erskine Esq., hath at his own expense provided arms and accoutred an independent company of Foot Militia in said County, do highly approve of his zeal in the same, and do order that he be commissioned as Captain of said Company.

Wm. Patterson, Sec’y [13]

While overseeing the training of his company, Erskine again put his mechanical talents to work, this time on behalf of America. He designed a tetrahedron-shaped marine cheval de frise that could be used to obstruct the Hudson River. On July 18, 1776 he forwarded the design to Gen. John Morin Scott of the New York militia. Erskine’s design was accompanied by a description:

Supposing, therefore, the Model to be before you, you will observe it consists of six pieces . . . the pieces represent beams a foot square and about 32 feet long. The nails which join the pieces represent bolts about 1 1/2 inches thick. The Carpenter work is very little, each piece having only two notches, bevelled 60 degrees, the angle of an equilateral triangle, and cut on one side about one-third of the thickness . . . There is but one right way of putting the model together . . . if the pieces are all of the same dimensions and the notches alike . . .The tetrahedron has four horned corners, numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, and three horns to each corner . . . [In 40 feet of water] any vessel being swept upon horns within 14 feet of the surface, would strike it . . . She would either be staked upon it, or her velocity over-set it, the other horns would then rise and take her in the bottom, or else she would break the “Chevaux-de-Frise” by her weight, which no ship could do without receiving such material damage as to render her unfit for service.[14]

A chain of chevaux de frise was begun at Fort Washington, but both Fort Washington on the New York side of the Hudson and Fort Lee on the New Jersey side fell to the British before it could be completed.

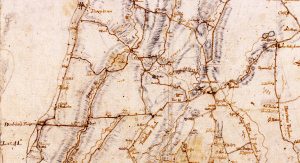

Gen. Charles Lee, knowing Erskine’s mapping skills, asked him to make a sketch of the countryside. Before Erskine could accomplish the task and deliver the sketch, Lee was captured by the British at Basking Ridge. A month later, Gen. George Washington petitioned Congress to allow him to establish a surveying and mapping department that would be attached to his headquarters. “The want of accurate Maps of the Country . . . has been of great disadvantage to me. I have in vain endeavoured to procure them and have been obliged to make shift, with such Sketches as I could trace out from my own Observations and that of the Gentlemen around me . . . If gentlemen of known character and probity could be employed in making maps from actual survey of the roads, of the rivers and bridges and fords over them, and of the mountains, and the passes through them, it would be of the greatest advantage.”[15] Nothing came of the request, however, Washington still needed maps of the countryside to determine routes of attack and retreat.

Lord Stirling, a friend of Erskine since they met in 1771 and now a brigadier general, recommended Erskine to Gen. Nathanael Greene to fill the vacancy of chief engineer to the army. The offer was extended, but Erskine respectfully declined it: “I cannot suppose myself qualified for such an office in many respects, particularly that part which relates to artillery, as I never saw a Bomb thrown in my life, nor a gun fired but at a Review or Birth day; but that branch, to which practical geometry and mechanics is necessary, I could undertake with some Confidence.”[16]

Gen. George Clinton, another friend, wrote to Erskine, “I wish you could have consented to have entered the service as Chief Engineer. I am confident, however diffident you may be with respect to your Qualifications, you could render your Country essential service in that Department.”[17]

In March 1777 Erskine visited Continental Army headquarters and apparently showed the map he had completed for General Lee. He wrote to General Clinton, “I intend going to Morristown again next Monday [March 31]. Lord Stirling has got many matereals, from which a map of the Jerseys may be made, which I have undertaken to form.”[18]

Two years later, in a letter to Gen. Philip Schuyler, Erskine mentioned this first map he made for the army. “In . . . 1777, I began to do business for the Public, by making a sketch of the Country for Genl. Lee; a map of the Jersies for His Excellency Genl. Washington from materials furnished by Lord Stirling; and a few trivial surveys at New Windsor; but did not engage fully in the Continental Service, or receive pay, till . . . 1778.”[19]

Washington and Erskine met again between July 11 and 13 when Washington was staying at his Pompton Headquarters.[20] It was here that Erskine handed Washington the map he had requested. Washington wrote to the Congress on July 19, “A good Geographer to Survey the roads and take sketches of the Country where the Army is to Act would be extremely useful and might be attended with exceeding valuable consequences . . . If such a person should be approved of I would beg leave to recommend Mr. Rbt. Erskine who is thoroughly skilled in this business and has already assisted us in making maps of the country.”[21]

On July 25, Congress responded: “Resolved . . . That General Washington be empowered to appoint Mr. Robert Erskine . . . geographer and surveyor of the roads, to take sketches of the country . . . and to have the procuring, governing and paying the guides under him; the General to affix the pay of the said geographer, & and . . . the guides.”[22]

Washington wasted no time in conveying Congress’s confirmation to Erskine. On July 28, he wrote, “I shall therefore be obliged to you to let me know without delay the conditions on which it will suit you to undertake [the position we discussed], and shall be glad to see you as soon as possible at HeadQuarters to fix the matter upon a proper footing . . . If you engage, your entrance upon the business will be immediately necessary.”[23]

Shortly after writing to Erskine, Washington and the Continental Army set off for Philadelphia where he believed the British army was headed. It was at Philadelphia that Washington probably received Erskine’s response: “The distinction you confer upon me, I beg leave to acknowledge with gratitude; and shall be happy to render every service in my power to your Excellency.” He informed Washington that for each surveyor, “six attendants . . . will be proper; to wit, two Chain-bearers, one to carry the [Plane-Table] Instrument, and three to hold flag staffs.” Each surveyor was to be paid two dollars per day and all reasonable travelling expenses when away from camp and each chain-bearer and flag staff holder was to be paid fifty cents per day. Erskine was to be paid four dollars per day and all reasonable travelling expenses when away from camp, and he made it clear that, “I cannot at present devote my whole time to the Department you have obligingly offered, Having . . . accounts to a large amount to settle and discharge in [my] present business . . . I can employ at least half my time in the Public Service; and by the opening off the next Campaign, perhaps the whole.”[24]

Having been a surveyor at the start of the French and Indian War, Washington was familiar with the demands required by the practice. Knowing that Erskine needed some time to make the necessary adjustments to his role at the mines, he had no problem agreeing to the terms. At this time the Ringwood mine and furnace had begun to manufacture some of the clips, links, and bolts that would be used to create the chain and boom that were to lay across the Hudson from Fort Montgomery on the New York side to Anthony’s Nose on the New Jersey side.

On November 14, Washington wrote to Erskine about another army order from the furnace, and inquired about the surveying position: “I shall be glad to know by Return of the Bearer whether the portable Ovens bespoke last summer are finished . . . Be pleased to let me know when you think you will be able to enter upon any of the duties of the Office which I spoke to you about last summer.”[25]

On the 24, Erskine responded, “The twenty Ovens ordered last Summer . . . were delivered as follows: four to Col. Mifflin . . . fourteen were sent after it to Morristown . . . and two large and two small ones to the care of Major Taylor at New Windsor.”[26] Upon receiving this letter, Washington knew he had selected the right man.

On March 26, 1778, Erskine sent a map of the Hudson Highlands to Washington, but the areas near West Point and between New Windsor and Haverstraw were unfinished. [27] On April 11, after reviewing the map, Washington wrote to Erskine from Valley Forge, “I recd yours of the 26th March inclosing an elegant draft of part of the Hudson River. If your affairs are in such a situation that they will admit of your attendance upon the Army, I shall be glad to see you as soon as possible.”[28]

Erskine arrived at Valley Forge on June 1. Four days later, Washington sent a dispatch to Capt. William Scull, who was conducting surveys near the camp. He wrote, “Robert Erskine Esq., who is appointed Military Surveyor, and Geographer is now here, endeavouring to arrange that department, fix upon the proper number of deputies, and settle their pay, appointments, etc.”[29]

Captain Scull was a member of the American Philosophical Society and the grandson of Nicholas Scull, the former surveyor-general for Pennsylvania. Washington wished for Erskine to report to camp to meet with Scull. There is no record of what was discussed at their meeting, but four weeks later Scull was officially reassigned to Erskine’s department. On June 20, Erskine hired Simeon DeWitt to serve as his “chief lieutenant;” over the following six months he hired nine more surveyors: Capt. William Gray, Capt. John Armtrong, Capt. William McMurray, Lt. Benjamin Lodge, Capt. John Watkins and four civilians: Elijah Porter of Connecticut, David Pye and Isaac Vrooman of New York and David Rittenhouse of Pennsylvania. The department would eventually have as many as six teams in the field at any one time.

On September 7, Erskine’s nephew, Ebenezer Erskine, arrived at Ringwood. His uncle had just returned home from the Continental Army’s camp at White Plains, New York where he had been for six weeks. According to the younger Erskine, on September 12, “Mr. E set out for the Camp [again] along with a Servt. and three Light Horsemen who are appointed to attend him.” Four weeks later, Ebenezer decided to visit his uncle who was now with General Washington at his headquarters in Pawling, New York. Shortly after his arrival on October 12, he was introduced to Washington who he described as “a very affable good-looking Man.” Ebenezer stayed with his uncle four days. Like his trip to Pawling, he was escorted by a light horseman on his return trip to Ringwood. Erskine would not return to Ringwood until November 11.[30] It is clear that Erskine was now not only devoting himself full-time to the drawing of maps, but he was also travelling with Washington.

The Ringwood mine and furnace were located midway between Washington’s winter headquarters at Middlebrook, New Jersey and the American posts along the Hudson River. Concerned for the safety of Erskine (when he was home) and everyone associated with the mine and furnace, Washington ordered a guard of a sergeant and twelve men to be placed at Ringwood in early December. [31] Two weeks later, Col. Thomas Clark, acting on Washington’s orders, stationed another fifty men and an officer at Kakiat, New York, northeast of Ringwood. Colonel Clark with his 1st and 2nd North Carolina regiments were stationed at Paramus New Jersey to the southeast of Ringwood.

With the spring campaigns not far off, on February 10, Washington wrote to Erskine, “As I think you are much exposed in your present situation . . . and the work in which you are employed unquestionably makes you an object with enemy—I desire that as soon as possible after receipt of this letter, you will remove to quarters more safe by the vicinity of the Army.”[32]

Erskine replied to Washington’s recommendation on February 26, but a copy of his letter is not among Washington’s papers. On March 3, Washington’s recommendation had now become a request: “Notwithstanding the many conveniences that would result from carrying on your work at your own House, I am still of opinion that convenience is over-balanced by the danger you are in, should the enemy think the draughts in which you are engaged worth their attention. I can assure you, your Work is no secret to them . . . Altho’ a small guard assisted by your own people may be sufficient to keep off the small parties of Villians . . . it would probably be otherwise with a party sent expressly to take your papers, which . . . would be infinitely valuable to them.”[33]

On March 20, Erskine informed Washington that Captain Scull was bringing all of his drawings and rough drafts to him and that while he was in Albany he had secured from a local surveyor “a Plan of Albany County, . . . besides which, I expect to procure several other useful plans; particularly Copies of the North and West branches of Hudsons River surveyed to their sources.”[34]

Washington visited Erskine’s home at Ringwood on June 5; he was enroute to New Windsor from his headquarters at Middlebrook. He enjoyed his surveyor-general’s hospitality and stayed the night. It is unclear if he departed for New Windsor the next day or the following. There are, however, four letters from Washington, dated Ringwood Iron Works, June 6, 1779: the first, to the President of the Congress; the second, to the Board of War; the third to John Jay; and the fourth to Major Henry Lee. His letters dated June 7, are written from Smith Tavern.

On July 3, Major General von Steuben received a brief note from Erskine: “Pursuant to His Excellency’s orders, I beg leave to transmit you the enclosed Draught of the adjacent Country—at the same time his Exy. desired me to mention it as His particular request that no Copies whatever be permitted to be taken of it.”[35]

It was a map of the Hudson Highlands that included all roads, rivers, mountains, fords, marshes, etc. A second map bearing the same date and directive was delivered to Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne. Less than two weeks later, Wayne led a daring nighttime attack on Stony Point. On August 19, Maj. Henry Lee led another successful assault—this time on the British-held position at Paulus Hook. Following these two defeats the British never made any further attempts to control the Hudson. It is likely that Erskine’s maps played a role in one or both of the victories.

By the fall of 1779, Ringwood had become a magazine and supply depot for the Continental Army. Moore Furman, the deputy quartermaster general of New Jersey wrote to David Banks, an assistant in the department, “I have received notice of a considerable Magazine of Provisions ordered to be formed at Ringwood Iron Works and that a Quantity of Forage will also be wanted there. . . . You will let me know by the first opportunity what quantity of Hay and Grass you think you can spare from your District.”[36]

On November 30, Washington made the decision to build his winter encampment at Morristown. On December 9, Erskine received a note from Tench Tilghman, an aide-de-camp to Washington: “His Excellency is extremely anxious to have the Roads in front and rear of the Camp accurately surveyed as speedily as possible. He therefore wishes to see you immediately at Head Quarters that he may give you particular directions as to the business which he wants executed.”[37]

When Erskine arrived in camp, Washington asked him to personally survey the roads and countryside about the camp; Erskine was able to complete the task before Christmas, even though “surveying was seriously handicapped by two feet of snow on the ground.”[38]

By the beginning of the new year, Erskine’s department had dwindled to a few surveyors; a principal reason was their pay. On May 7, 1780, Erskine wrote a long letter to Gen. Philip Schuyler, a member of the Continental Congress, who was assisting Washington in the reorganization of the departments. Included with it was a letter from some of the remaining surveyors:

The officers in the line of the Army, have received a considerable addition to their pay, under the denomination of subsistence money; besides the benefit of State supplies: and the wages of other Departments of the Army, whose pay was formerly less than ours, has been greatly augmented while we have been entirely overlooked . . . Our pay, so far from supplying us with clothes, has not been adequate, for these twelve months past, to furnish us with shoes . . . If therefore the continuance of our Service be thought necessary, we have no doubt that the Surveying Department will . . . make up for the Depreciation and fix our pay.

Erskine continued, “Upon this letter I shall beg leave to observe, that His Excellency, Genl. Washington, has seen it, and is of the opinion that the allegations it contains are reasonable.”[39] It is unknown if the pay increase was ever granted.

Ringwood had become such an important supply depot for the Continental Army that Washington had to increase the number of guards stationed there following the skirmish at Springfield on June 23. His orders on June 30 stated, “Colonel Livingston’s regiment will take Post in the Clove near the old Barracks, and joined by the detachment of General Clinton’s brigade, already there will furnish such Guards as may be necessary for the Security of the Stores at Ringwood.”[40]

With only a few surveyors in the department, Erskine was out in the field more often. Sadly, on September 18, according to his nephew, Ebenezer, Erskine “caught a severe cold and sore throat, which produced fever, and within the space of a fortnight terminated in his dissolution.”

It is likely that Erskine died of pneumonia. His obituary in the New Jersey Gazette read,

Died the 2d instant, at his house in Ringwood, ROBERT ERSKINE, F.R.S. and Geographer to the Army of the United States, in whom were united the Christian and the Gentleman. His integrity and unbounded benevolence have rendered his death a loss to the publick, and a subject of sincere regret to all his acquaintances. He made the laws of justice the invariable rule of his conduct, and upon this principle espoused the cause of America, in which he served his country with approbation and universal esteem.[41]

On December 4, 1780, with Washington’s recommendation, Simeon de Witt was appointed the new Geographer and Surveyor-General. The work of Erskine’s department had become so integral to the war efforts that on May 4, 1781, Capt. Thomas Hutchins was appointed the “Geographer to the army acting in the South . . . the pay and emoluments of the said Hurchins, be the same as those of the Geographer to the Northern Main Army.[42]

In the course of his four years, Robert Erskine and his surveyors supplied Washington with an estimated 275 maps. Without them, the war might have unfolded very differently.

[1]Albert Heusser, George Washington’s Map Maker, a Biography of Robert Erskine (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1966), 16-18.

[2]Robert Erskine, Engineer Papers, 1756-1780 (Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1859), Manuscript Group 199.

[3]Heusser, George Washington’s Map Maker, 21, 24.

[5]New Jersey Archives, First Series, Vol. XXVIII, 247 ff.

[6]“Biographical Essay on Robert Erskine, 1735-1780,” in Historical Resources (Ringwood, NJ: North Jersey Highlands Historical Society,1958).

[7]Heusser, George Washington’s Map Maker, 45; Albert Heusser, The Manor and Forges of Ringwood (Newark, NJ: New Jersey State Library Archives, 1920), 1: 30, 32, 37-39; 2: 4, 5, 7, 10, 12, 14; 3: 24.

[10]The History of Morris County, New Jersey (W.W. Munsell & Co., New York, 1882).

[11]Joseph F. Tuttle, “Essay read before the New Jersey Historical Society, May 20, 1869,” New Jersey Archives, Second Series, Vol. II (1869).

[12]Heusser, George Washington Map Maker, 139; “Robert Erskine Timeline,” in Historical Resources (Ringwood, NJ: North Jersey Highlands Historical Society, 1958).

[13]Joseph F. Tuttle, “The Early History of Morris County, New Jersey,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, Second Series, Col. II (1869), 33-34.

[14]Heusser, The Manor and Forges of Ringwood, 1: 65.

[15]“George Washington to the President of Congress, 26 January 1777,” The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources (1745-1799), ed., John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington DC: G.P.O., 1931-33), 7: 63-68.

[16]Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York (New York: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., 1899), 1: 660.

[19]“Robert Erskine to General Philip Schuyler, 7 February 1780,” The Papers of the Continental Congress compiled by John P. Butler (1978) Transcript, m247, r22, i11, 4:265; Lawrence Martin, ed., The George Washington Atlas (Washington DC: United States Bicentennial Commission, 1932), Plate 14. The map for Washington is actually four separate pieces of paper that together measure 24 ½ inches by 38 ½ inches. Washington carried this map on his person for much of the war. It is tattered and stained from use and is annotated by Washington in sixteen places. The original map may be found in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City. It was probably given to Washington by Erskine when they met in July of 1778.

[20]Magazine of American History, 3: 158.

[21]“From George Washington to the Continental Congress Committee to Inquire into the State of the Army, 19 July 1777,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2000), 10: 332-337.

[22]Journals of the Continental Congress, 25 July, 1777, 8: 580.

[23]“From George Washington to Robert Erskine, 28 July 1777,” The Papers of George Washington, 10: 444.

[24]“To George Washington from Robert Erskine, 1 August 1777,” ibid., 10: 476-479.

[25]“From George Washington to Robert Erskine, 14 November 1777,” ibid., 12: 250-51.

[26]“To George Washington from Robert Erskine, 24 November 1777,” ibid., 12: 375-76.

[27]‘To George Washington from Robert Erskine, 26 March 1778,” ibid., 14: 318.

[28]Ibid., “From George Washington to Robert Erskine, 11 April 1778,” 14:476.

[29]“From George Washington to Captain William Scull, 5 June 1778,” ibid., 15: 328-29.

[30]“The Diary of Ebenezer Erskine, Jr., 1778,” North Jersey Highlander (Ringwood, NJ: North Jersey Highlander Historical Society, 1967), 3 (Spring),18-21.

[31]“From George Washington to Colonel Thomas Clark, 4-7 December 1778,” The Papers of George Washington, 18: 360-62.

[32]“From George Washington to Robert Erskine, 10 February 1779,” ibid., 19: 166.

[33]“From George Washington to Robert Erskine, 3 March 1779,” ibid., 19: 339-40.

[34]“To George Washington from Robert Erskine, 20 March 1779,” ibid., 19: 535-36.

[35]Albert Heusser, The Forgotten General: Robert Erskine, F.R.S. (Paterson, NJ: The Benjamin Franklin Press, c1928), 154.

[36]“Moore Furman to David Banks, 27 September 1779,” ibid., 156.

[37]“From Tench Tilghman to Robert Erskine, 9 December 1779,” The Writings of George Washington, 17: 240; the map of Morristown is in the New York Historical Society, number 105.

[38]These maps, #105 and #118, are preserved in the New York Historical Society; Huesser: The Forgotten General, 163.

[39]“Robert Erskine to General Philip Schuyler, 7 February 1780,” The Papers of the Continental Congress, transcript m247, r22, i11, 4: 265.

[40]The Writings of George Washington, 19: 100.

[41]New Jersey Gazette, October 18, 1780.

[42]Journals of the Continental Congress, May 4, 1781, 20: 475-76.

9 Comments

I have organized a groundbreaking symposium http://www.horology1776.com October 1-3, 2020, at the Museum of the American Revolution, focusing on timekeeping during the War. I know that surveyors used accurate timepieces in their work, and also that clock/instrument makers like Rittenhouse and Duffield made surveying instruments. If you have material relevant to the conference, I would be happy to consider you as a speaker. Thanks for your research, writing, and consideration. Of course, all readers are encouraged to attend and participate.

extremely interesting piece on erskine

Great article about Erskine. Readers may also like learning about his replacement, Simeon DeWitt, who served with Washington throughout the remainder of the Revolutionary War and later became the Surveyor General for New York State. DeWitt’s life story is told in detail in my book, Jacob’s Land: Revolutionary War Soldiers, Schemers, Scoundrels and the Settling of New York’s Frontier. The book received high reviews in an earlier edition of the Journal of the American Revolution.

Bob, I enjoyed your Erskine in depth research article. You noted Erskine hired Capt. William McMurray (later the former assistant to geographer Hutchins & 1st American “professional” cartographer to produce the 1784 map of the new nation). Can you direct me to your primary sources of this hiring detail / McMurray. Thanks.

This is an absolutely wonderful article about a man who was unknown to me (and, I’ll bet, most Americans) but who should not be.

“The only thing new is the history you don’t know.” – Harry S. Truman.

That is so true, indeed, and it’s why I keep on coming to JAR, daily, for things for which I should be aware of, but am not, and they are truly equipped to inform me of those things. Seriously great article on a great man. Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to JAR!

I graduated from Erskine College in South Carolina. The school was founded in 1839 by the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church and named in honor of Scottish ministers/brothers Ralph and Ebenezer Erskine. I had no idea that Ralph’s son was a brilliant inventor who contributed his many talents to the patriot cause. Thanks for your informative and interesting article!

I am always happy to see articles about Robert Erskine, who because of his highly secret and important post as Geographer to the Army, his importance has been overlooked, and his name was sort of forgotten. Also his early death on 2 October, 1780 was a big factor in his being “forgotten”. It is my opinion that if any one person could be credited with winning the Revolution it would be Erskine because he drew the maps upon which General Washington mapped his strategy which gave him a better knowledge of the “lay of the land”; because of their accuracy. I studied Robert Erskine 40 years, and I’m happy to see articles about Robert Erskine

Asking for clarification. I think Anthony’s Nose is the mountain on the other side of the Bear Mountain Bridge. That is currently NY. I don’t think it was ever a part of NJ.

From 1972 to 1996, the Defense Mapping Agency was housed in the Robert Erskine Building in Bethesda MD.