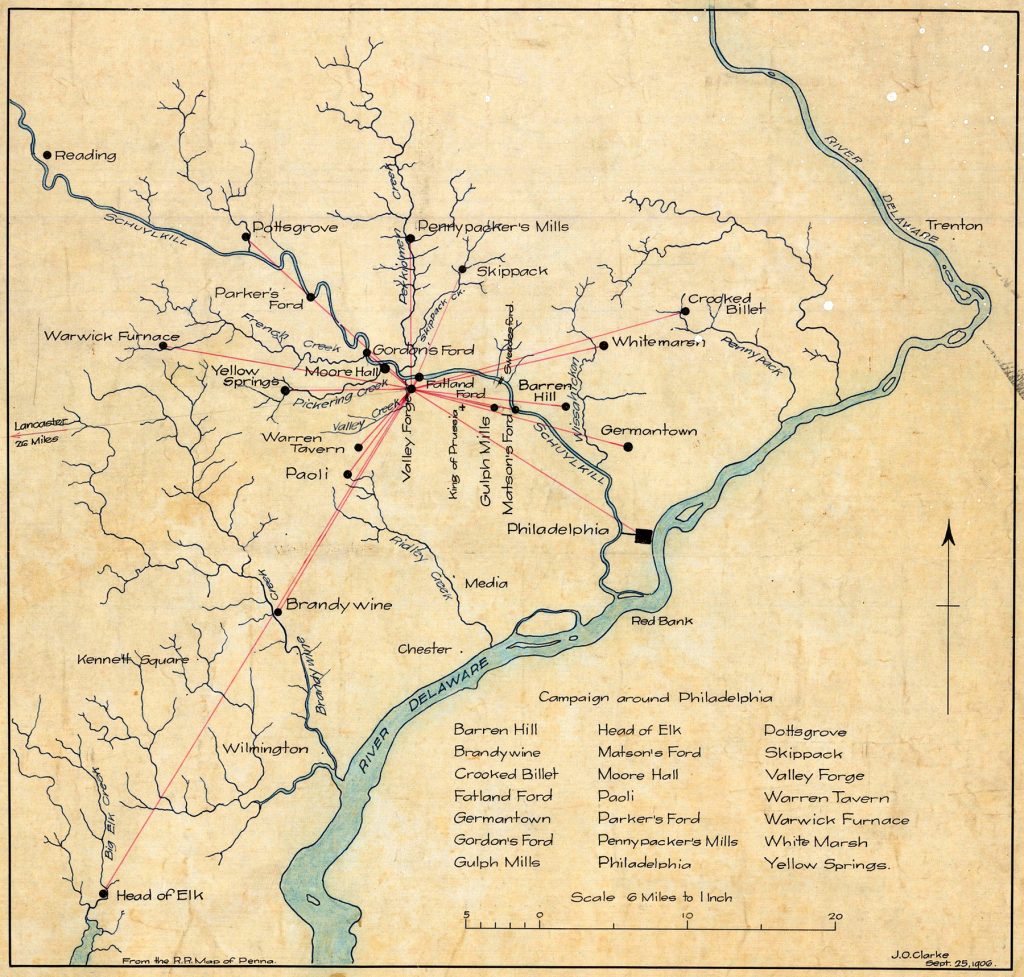

William Trego’s painting The March to Valley Forge is iconic. Where the Continental Army marched from has been largely overlooked. That march was from The Conshohocken or Gulph Hills, in Upper Merion Township, about seven miles from Valley Forge, where the army encamped from December 13 to 19, 1777. As one historian noted, “These grounds were the threshold to Valley Forge, and the story of that winter—a story of endurance, forbearance, and patriotism which will never grow old—had its beginnings here, at the six days encampment by the old Gulph Mill.”[1]

Those six days were a microcosm of the Revolutionary War.

Day 1. December 13, 1777: The March In

Late in the evening of December 12, in a blinding snowstorm, Washington and his hungry, tired, and barely-clothed army marched over the Schuylkill River at Swedes Ford, in present day Norristown, and down to Gulph Mills. Dr. Albigence Waldo, Surgeon General to the Continental Army and a member of the Connecticut Brigade, wrote, “We are ordered to march over the river. It snows–I’m sick–eat nothing–no whiskey–no baggage–Lord-Lord-Lord–. Till sunrise crossing the river cold and uncomfortable.”[2]Another wrote, “at 3 a.m. encamped near the Gulph where we remained without tents or blankets in the midst of a severe snow storm.”[3]

Because of its elevation, the highest hill in Gulph Mills allowed the army to see the British advancing from Philadelphia to the east.[4] General Washington had to get his army, which had no tents, settled. Lt. Samuel Armstrong wrote of the soldiers’ efforts to build shelter, “This day One man was killed and One Wounded so bad his life is Dispaired of, which happened by the falling of Trees.”[5] Washington issued these orders[6]:

GENERAL ORDERS December 13, 1777

Head-Quarters, at the Gulph,

Parole Carlisle. Countersigns Potsgrove, White Marsh.

The officers are without delay to examine the arms and accoutrements of their men, and see that they are put in good order.

Provisions are to be drawn, and cooked for to morrow and next day. A gill of Whiskey is to be issued immediately to each officer, soldier, and waggoner.

The weather being likely to be fair, the tents are not to be pitched. But the axes in the waggons are to be sent for, without delay, that the men may make fires and hut themselves for the ensuing night in the most comfortable manner.

The army is to be ready to march precisely at four o’clock to morrow morning.

An officer from each regiment is to be sent forthwith to the encampment on the other side

Schuylkill, to search that and the houses for all stragglers, and bring them up to their corps. All the waggons not yet over are also to be sent for and got over as soon as possible.

Day 2. December 14, 1777: Hardship

The soldier’s tents were not to arrive for two days. Food was scarce. Dr. Waldo wrote, “Why are we sent here to starve and Freeze . . . Here all Confusion—smoke and Cold—hunger and filthyness—A pox on my bad luck.”[7]

Washington issued orders to settle the troops.[8] Also, he wrote to the President of Congress about the army’s movement to “the Gulph” and the December 11 skirmishes.[9]

To THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS

Head Quarters near the Gulph, December 14, 1777.

On Thursday morning we marched from our Old Encampment and intended to pass the Schuylkill at Madisons Ford [Matson’s Ford],where a Bridge had been laid across the River. When the first Division and a part of the Second had passed, they found a body of the Enemy, consisting, from the best accounts we have been able to obtain, of Four Thousand Men, under Lord Cornwallis possessing themselves of the Heights on both sides of the Road leading from the River and the defile called the Gulph, which I presume, are well known to some part of your Honble. Body. This unexpected Event obliged such of our Troops, as had crossed to repass and prevented our getting over till the succeeding night. This Manoeuvre on the part of the Enemy, was not in consequence of any information they had of our movement, but was designed to secure the pass whilst they were foraging in the Neighbouring Country; they were met in their advance, by General Potter with part of the Pennsylvania Militia, who behaved with bravery and gave them every possible opposition, till they were obliged to retreat from their superior numbers. Had we been an Hour sooner, or had had the least information of the measure, I am persuaded we should have given his Lordship a fortunate stroke or obliged him to have returned, without effecting his purpose, or drawn out all Genl Howe’s force to have supported him. Our first intelligence was that it was all out. He collected a good deal of Forage and returned to the City, the Night we passed the River. No discrimination marked his proceedings.

All property, whether Friends or Foes that came in their way was seized and carried off.

Day 3. December 15, 1777: The Army Settles Down

The army settled down and recouped some strength. Dr. Waldo wrote, “Quiet. Eat Pessimmens, found myself better for their Lenient Opperation. Went to a house, poor and small, but good food within—eat too much from being so long Abstemious, thro’ want of palatables.”[10]

Washington had not yet selected winter quarters, despite much deliberation with his generals, the Continental Congress, and the Pennsylvania legislatures.[11]Areas under consideration included those west of Philadelphia, like Gulph Mills,[12]Lancaster and Wilmington, Delaware.[13]The British had already settled into a relatively comfortable winter in Philadelphia.

South Carolinian Lt. Col. John Laurens, aide-de-camp to George Washington, wrote about winter headquarters in a letter to his father, “The precise position is not yet fixed upon, in which our huts are to be constructed; it will probably be determined today; it must be in such a situation as to admit of a bridge of communication over the Schuylkill for the protection of the country we have just left.”[14]

In one of his letters, Washington ordered the army to comply with the Continental Congress’s December 10 order to Washington to forage for food and resources from local homes and businesses.[15] Washington’s wrote to Congress that his army already foraged and of the impact on the locals.[16]

To THE OFFICERS ORDERED TO REMOVE PROVISIONS FROM THE COUNTRY NEAR THE ENEMY [Headquarters, December 15, 1777.]

In Congress, December 10, 1777. Resolved . . . [Extract from the proceedings of Congress.]

Sir: You will perceive by the foregoing Extracts, that it is the direction of Congress, that the Army should be subsisted, as far as possible, on provisions to be drawn from such parts of the Country, as are within its vicinity and most exposed to the ravages and incursions of the Enemy.

To the President of Congress

December 15. [attached to General Washington’s letter dated December 14]

Your Favor of the 11th Current, with its Inclosure came to hand Yesterday. Congress seem to have taken for granted a Fact, that is really not so. All the Forage for the Army has been constantly drawn from Bucks and Philadelphia Counties and those parts most contiguous to the City, insomuch that it was nearly exhausted and intirely so in the Country below our Camp. From these too, were obtained all the Supplies of flour that circumstances would admit of. The Millers, in most instances, were unwilling to grind, either from their disaffection or from motives of fear. This made the supplies less than they otherwise might have been, and the Quantity which was drawn from thence, was little besides what the Guards, placed at the Mills, compelled them to manufacture. As to Stock, I do not know that much was had from thence, nor do I know that any considerable supply could have been had. I confess, I have felt myself greatly embarrassed with respect to a vigorous exercise of Military power. An Ill placed humanity perhaps and a reluctance to give distress may have restrained me too far. But these were not all. I have been well aware of the prevalent jealousy of military power, and that this has been considered as an Evil much to be apprehended even by the best and most sensible among us. Under this Idea, I have been cautious and wished to avoid as much as possible any Act that might improve it. However Congress may be assured, that no exertions of mine as far as circumstances will admit shall be wanting to provide our own Troops with Supplies on the one hand, and to prevent the Enemy from them on the other. At the same time they must be apprized, that many Obstacles have arisen to render the former more precarious and difficult than they usually were from a change in the Commissary’s department at a very critical and interesting period. I should be happy, if the Civil Authority in the Several States thro’ the recommendations of Congress, or their own mere will, seeing the necessity of supporting the Army, would always adopt the most spirited measures, suited to the end. The people at large are governed much by Custom. To Acts of Legislation or Civil Authority they have been ever taught to yield a willing obedience without reasoning about their propriety. On those of Military power, whether immediate or derived originally from another Source, they have ever looked with a jealous and suspicious Eye.

Washington also wrote to Rhode Island Governor Jonathan Trumbull requesting troops and clothing.[17]

To Governor Jonathan Trumbull Head Quarters, Gulf Mill, December 15, 1777.

Sir:

I observe by the Copy of your letter to Congress, that your State had fallen upon means to supply your troops with Cloathing, I must earnestly beg that it may be sent on to Camp as fast as it is collected. To cover the Country more effectually we shall be obliged to lay in a Manner in the Field the whole Winter, and except the Men are warmly clad they must suffer much. Among the troops of your State there are 363 drafts whose time of Service will expire with this Month. This deduction, with the former deficiency of the Regiments, will reduce them exceedingly low and as I have represented this Matter to Congress very fully I hope they have before this time urged to the States the necessity which there is of filling their Regiments this Winter. But lest they should not have done it, I beg leave to urge the matter to your immediate consideration. Recruits for the War ought by all means, to be obtained if possible; but if that cannot be done, drafts for one year at least should be called out without delay; and I hope that as many as are now upon the point of going home, will be immediately reinstated. We must expect to loose a considerable number of Men by sickness and otherways, in the course of the Winter and if we cannot take the field in the Spring with a superior or at least an equal force with the Enemy, we shall have laboured thro’ the preceeding Campaigns to little purpose.

Day 4. December 16, 1777: Tents Arrive and British Soldiers are Captured

On a cold and rainy December 16, the tents arrived, to the soldiers’ comfort.[18] Washington’s orders were short and sweet:[19]

General Orders Head. Quarters, at the Gulph, December 16, 1777.

Parole—. Countersigns—.

The tents are to be carried to the encampment of the troops, and pitched immediately.

Also on the 16th, a British foraging party ran into the Continental Army. One soldier wrote, “We have been for several days past posted on the mountains near the gulph mill, and [today], a party of the enemy, to the number of fourty five were surprised and made prisioners.”[20]

Day 5. December 17, 1777: Washington Announces the Move to Valley Forge and prepares for the new Nation’s First Thanksgiving Celebration

After weeks of debate, Washington decided on Valley Forge for the Continental Army’s winter quarters. He explained that decision in eloquent and moving general orders.[21] He delayed the march for a day so the army could celebrate the new nation’s first Thanksgiving and first official holiday. The Continental Congress, on November 1, 1777, proclaimed that on December 18, 1777, the nation would stop and give thanks to God for blessing the nation and the troops in their quest for independence and peace.[22]

GENERAL ORDERS Head Quarters, at the Gulph, December 17, 1777.

The Commander-in-Chief with the highest satisfaction expresses his thanks to the officers and soldiers for the fortitude and patience with which they have sustained the fatigues of the Campaign. Altho’ in some instances we unfortunately failed, yet upon the whole Heaven hath smiled on our Arms and crowned them with signal success; and we may upon the best grounds conclude, that by a spirited continuance of the measures necessary for our defence we shall finally obtain the end of our Warfare, Independence, Liberty and Peace. These are blessings worth contending for at every hazard. But we hazard nothing. The power of America alone, duly exerted, would have nothing to dread from the force of Britain. Yet we stand not wholly upon our ground. France yields us every aid we ask, and there are reasons to believe the period is not very distant, when she will take a more active part, by declaring war against the British Crown. Every motive therefore, irresistibly urges us, nay commands us, to a firm and manly perseverance in our opposition to our cruel oppressors, to slight difficulties, endure hardships, and condemn every danger. The General ardently wishes it were now in his power, to conduct the troops into the best winter quarters. But where are these to be found ? Should we retire to the interior parts of the State, we should find them crowded with virtuous citizens, who, sacrificing their all, have left Philadelphia, and fled thither for protection. To their distresses humanity forbids us to add. This is not all, we should leave a vast extent of fertile country to be despoiled and ravaged by the enemy, from which they would draw vast supplies, and where many of our firm friends would be exposed to all the miseries of the most insulting and wanton depredation. A train of evils might be enumerated, but these will suffice. These considerations make it indispensibly necessary for the army to take such a position, as will enable it most effectually to prevent distress and to give the most extensive security; and in that position we must make ourselves the best shelter in our power. With activity and diligence Huts may be erected that will be warm and dry. In these the troops will be compact, more secure against surprises than if in a divided state and at hand to protect the country. These cogent reasons have determined the General to take post in the neighbourhood of this camp; and influenced by them, he persuades himself, that the officers and soldiers, with one heart, and one mind, will resolve to surmount every difficulty, with a fortitude and patience, be coming their profession, and the sacred cause in which they are engaged. He himself will share in the hardship, and partake of every inconvenience.

To morrow being the day set apart by the Honorable Congress for public Thanksgiving and Praise; and duty calling us devoutely to express our grateful acknowledgements to God for the manifold blessings he has granted us. The General directs that the army remain in it’spresent quarters, and that the Chaplains perform divine service with their several Corps and brigades. And earnestly exhorts, all officers and soldiers, whose absence is not indispensibly necessary, to attend with reverence the solemnities of the day.

Day 6. December 18, 1777: Washington’s Army Celebrates the Nation’s First Thanksgiving and Prepares for Camp at Valley Forge

Reverend Israel Evans, Chaplin to General Poor’s New Hampshire brigade, preached at least one of the Thanksgiving sermons. Evans’ sermon was printed by Lancaster, Pennsylvania printer Francis Bailey who was credited as the first printer to name, in print, Washington as “the Father of His Country.”[23] Washington received a copy of Evans’ Thanksgiving sermon on March 12, 1778. The next day, he thanked Evans:

To REVEREND ISRAEL EVANS

Head Qrs. Valley-forge, March 13, 1778.

Revd. Sir: Your favor of the 17th. Ulto., inclosing the discourse which you delivered on the 18th. of December; the day set a part for a general thanksgiving; to Genl. Poors Brigade, never came to my hands till yesterday. I have read this performance with equal attention and pleasure, and at the same time that I admire, and feel the force of the reasoning which you have displayed through the whole, it is more especially incumbent upon me to thank you for the honorable, but partial mention you have made of my character; and to assure you, that it will ever be the first wish of my heart to aid your pious endeavours to inculcate a due sense of the dependance we ought to place in that all wise and powerful Being on whom alone our success depends; and moreover, to assure you, that with respect and regard, I am, etc.” [cite]

For the army, the first Thanksgiving celebration of the new nation lacked abundant food and comfort, even though conditions had improved for some. Dr. Waldo wrote, “Universal Thanksgiving—a Roasted pig at Night. God be thanked for my health which I have pretty well recovered.”[24]

Lt. Samuel Armstrong wrote, “We had neither Bread nor meat ‘till just before night when we had some fresh Beef, without any Bread or flour, The Beef wou’d have Answer’ to have made Minced Pis if it cou’d bee made tender Enough, but it seem’d Mr. Commissary did not intend that we Shou’d keep a Day of rejoicing—but however we Sent out a Scout for some fowls and by Night he Return’d with one Dozn: we distributed five of them among our fellow sufferers three we Roasted two we boil’d and Borrowed a few Potatoes[.] upon these we Supp’d without any Bread or anything Stronger than Water to drink!”[25]

Washington’s orders largely focused on setting up the Valley Forge camp, particularly the procedure for building huts. His very specific orders included a $12 award for thesoldiers in each regiment who finished their hut first and a $100 award for any soldier who invented a hut covering that was cheaper and quicker made than boards, which were in short supply.[26]

GENERAL ORDERS Head Quarters, at the Gulph, December 18, 1777

The Major Generals and officers commanding divisions, are to appoint an active field officer in and for each of their respective brigades, to superintend the business of hurting, agreeably to the directions they shall receive; and in addition to these, the commanding officer of each regiment is to appoint an officer to oversee the building of huts for his own regiment; which officer is to take his orders from the field officer of the brigade he belongs to, who is to mark out the precise spot, that every hut, for officers and soldiers, is to be placed on, that uniformity and order may be observed . . .

The Colonels, or commanding officers of regiments, with their Captains, are immediately to cause their men to be divided into squads of twelve, and see that each squad have their proportion of tools, and set about a hut for themselves: And as an encouragement to industry and art, the General promises to reward the party in each regiment, which finishes their hut in the quickest, and most workmanlike manner, with twelve dollars. And as there is reason to believe, that boards, for covering, may be found scarce and difficult to be got; He offers One hundred dollars to any officer or soldier, who in the opinion of three Gentlemen, he shall appoint as judges, shall substitute some other covering, that may be cheaper and quicker made, and will in every respect answer the end.

The Soldier’s huts are to be of the following dimensions, viz: fourteen by sixteen each, sides, ends and roofs made with logs, and the roof made tight with split slabs, or in some other way; the sides made tight with clay, fire-place made of wood and secured with clay on the inside eighteen inches thick, this fireplace to be in the rear of the hut; the door to be in the end next the street; the doors to be made of split oak-slabs, unless boards can be procured. Side-walls to be six and a half feet high. The officers huts to form a line in the rear of the troops, one hut to be allowed to each General Officer, one to the Staff of each brigade, one to the field officers of each regiment, one to the Staff of each regiment, one to the commissioned officers of two companies, and one to every twelve non-commissioned officers and soldiers.

On December 19 at around 10 a.m., Washington and his Continental Army marched out of Rebel Hill and Gulph Mills, past the Hanging Rock, down Gulph Road, and on to Valley Forge.

Washington Irving described the march in his book, Life of Washington. “Sad and dreary was the march to Valley Forge, uncheered by the recollection of any recent triumph . . . Hungry and cold were the poor fellows who had so long been keeping the field . . . provisions were scant, clothing was worn out, and so badly were they off for shoes, that the footsteps of many might be tracked in blood.”[27]

Lt. Armstrong wrote: “Friday ye 19th. The Sun Shone out this morning being the first time I had seen it for Seven days, which seem’d to put new Life into everything—We took the Remains of two Days Allowance of Beef . . . and two fowls we had left, of these we made a broth upon which we Breakfasted with half a loaf of Bread we Begg’d and bought, of which we shoud have had made a tolerable Breakfast, if there had been Enough!! By ten Oclock we [had] to march to a place Call’d Valley Forge being about five or six miles—about Eleven Ock we Sit out, but did not arrive there ‘till after Sun Sit. During this march we had noting to eat or nor to drink.”[28]

Washington wrote three letters on December 19.

To PRESIDENT GEORGE READ Head Quarters, Gulf Mill, December 19, 1777.

Sir: I have received information, which I have great reason to believe is true, that the Enemy mean to establish a post at Wilmington, for the purpose of Countenancing the disaffected in the Delaware State, drawing supplies from that Country and the lower parts of Chester County, and securing a post upon Delaware River during the Winter. As the advantages resulting to the Enemy from such a position are most obvious, I have determined and shall accordingly, this day send off General Smallwood with a respectable Continental force to take post at Wilmington before them. If Genl. Howe thinks the place of that Importance to him, which I conceive it is, he will probably attempt to dispossess us of it; and, as the force, which I can at present spare, is not adequate to making it perfectly secure, I expect that you will call out as many Militia as you possibly can to rendezvous without loss of time at Wilmington, and put themselves under the Command of Genl. Smallwood. I shall hope that the people will turn out cheerfully, when they consider that they are called upon to remain within, and defend, their own state.[29]

To GOVERNOR PATRICK HENRY Camp 14 Miles from Philadelphia, December 19, 1777.

Sir: On Saturday Evening I was honored with your favor of the 6th. Instant, and am much obliged by your exertions for Cloathing the Virginia Troops. The Articles you send shall be applied to their use, agreeable to your wishes. It will be difficult for me to determine when the Troops are supplied, owing to their fluctuating and deficient state at present; However I believe there will be little reason to suspect that the quantities that may be procured, will much exceed the necessary demands. It will be a happy circumstance, and of great saving, if we should be able in future to Cloath our Army comfortably. Their sufferings hitherto have been great, and from our deficiencies in this instance, we have lost many men and have generally been deprived of a large proportion of our Force. [30]

To BRIGADIER GENERAL WILLIAM SMALLWOOD Gulph Mill, December 19, 1777.

Dr. Sir: With the Division lately commanded by Genl. Sullivan, you are to March immediately for Wilmington, and take Post there. You are not to delay a moment in putting the place in the best posture of defence, to do which, and for the security of it afterwards, I have written in urgent terms to the President of the Delaware State to give every aid he possibly can of Militia. I have also directed an Engineer to attend you for the purpose of constructing, and superintending the Works, and you will fix with the Quarter Master on the number of Tools necessary for the business; but do not let any neglect, or deficiency on his part, impede your operations, as you are hereby vested with full power to sieze and take (passing receipts) such articles as are wanted. [31]

Gulph Mills went on to serve as an outpost, headed by Aaron Burr, during the Valley Forge encampment.[32] It also served as a place of retreat for General Lafayette and some two thousand troops after the Battle of Barren Hill on May 20, 1778.[33]

The highest hill in Gulph Mills was then referred to in the community and by topographers as Rebel Hill, which was thought to have gotten its name because of its significance during the Gulph Mills encampment and the rebels and patriots who resided there.[34] General Lord Stirling, with his aide-de-camp, James Monroe, were housed on top of the hill when, during the Valley Forge encampment, Stirling commanded an outpost that ran southwest of the Schuylkill River for several miles.[35]

[1]Samuel Gordon Smyth, “The Gulph Hills in the Annals of the Revolution,” Historical Sketches of Montgomery County (Norristown, PA: The Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1905), 3: 171.

[2]Albigence Waldo, “Valley Forge, 1777-1778. Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Philadelphia, PA: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1897), 21: 305, www.jstor.org/stable/20085750, accessed September 24, 2019.

[3]James Mcmichael, “The Diary Of Lieutenant James Mcmichael, Of The Pennsylvania Line, 1776-1778,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History And Biography (Philadelphia, PA: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1892) Xvi: 157.

[4]Smyth, “The Gulph Hills in the Annals of the Revolution,” 174.

[5]Joseph Lee Boyle, “NOTES AND DOCUMENTS, From Saratoga to Valley Forge: The Diary of Lt. Samuel Armstrong,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Philadelphia, PA: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1997), 121: 256 – 257.

[6]“General Orders, 13 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0549, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002), 602–603).

[7]Waldo, “Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line,” 306 – 307.

[8]“General Orders, 14 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0550, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 603).

[9]“From George Washington to Henry Laurens, 14–15 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0553, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 604–607).

[10]Waldo, “Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line,” 307.

[11]See source note to Washington’s General Orders from November 30, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0435#GEWN-03-12-02-0435-sn (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 444-445).

[12]William S. Baker, “The Camp by the Old Gulph Mill,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Philadelphia, PA: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1893), 17: 429, www.jstor.org/stable/20083558, accessed September 24, 2019.

[13]For an example of the generals’ responses to Washington, see “To George Washington from Major General Nathanael Greene, 1 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0445, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 459–463).

[14]John Laurens, The Army Correspondence of Colonel John Laurens in the Years 1777-8 (New York, NY: The Bradford Club, 1867), 93 – 94, archive.org/details/armylaurensyear00johnrich/page/92, accessed October 22, 2019.

[15]“Orders to Commissaries and Quartermasters, 15 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0558, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 611–612).

[16]“From George Washington to Henry Laurens, 14–15 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0553, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 604–607).

[17]“From George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., 15 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0560, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 612–613).

[18]Waldo, “Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line,” 308.

[19]“General Orders, 16 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0561, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 613–614).

[20]Baker, “The Camp by the Old Gulph Mill,” 426, fn. 1.

[21]“General Orders, 17 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0566, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source:The Papers of George Washington, 12: 620–621).

[22]A Proclamation for a General Thanksgiving Throughout the United States of America, November 1, 1777. Second Continental Congress. Cha. Thompson, Secretary.

[23]Israel Evans, A discourse, delivered, on the 18th day of December, 1777, the day of public thanksgiving, appointed by the Honourable Continental Congress : by the Reverend Israel Evans, A.M. Chaplain to General Poor’s brigade. And now published at the request of the general and officer of the said brigade, to be distributed among the soldiers, gratis (Lancaster, PA: Printed by Francis Bailey, 1778). Bailey was the first to name George Washington “Father of his County,” when the cover of his 1779 almanac called “Waschington” “Des Landes Vater.” The Black Art, A History of Printing in Lancaster, PA, Lee J. Stoltzfus,www.lancasterlyrics.com/g_francis_bailey/index.html, accessed September 24, 2019.

[24]Waldo, “Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line,” 308.

[25]Boyle, “From Saratoga to Valley Forge: The Diary of Lt. Samuel Armstrong,” 257.

[26]“General Orders, 18 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0573, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 626–628).

[27]Washington Irving, The Life of Washington, Volume III, (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell and Company, 1865), 306 – 308.

[28]Boyle, “From Saratoga to Valley Forge: The Diary of Lt. Samuel Armstrong,” 258.

[29]“From George Washington to George Read, 19 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0582, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 639–640).

[30]“From George Washington to Patrick Henry, 19 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0579, accessed April 11, 2019(original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 636–637).

[31]“From George Washington to Brigadier General William Smallwood, 19 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0583, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, 12: 641).

[32]“The Overhanging Rock at Gulph Mills,”www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/history/rock.html, accessed September 23, 2019.

[33]“From George Washington to Major General Lafayette, 18 May 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0152, accessed April 11, 2019 (original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 15, May–June 1778, ed. Edward G. Lengel (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 151–154).

[34]M. Regina Stiteler Supplee, “Gulph Mills and Rebel Hill,” Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County Pennsylvania (Norristown, PA: The Historical Society of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1947), 6: 17.

[35]Henry Woodman, The History of Valley Forge (Oaks, PA: John Francis, Sr., 1922), 60.

2 Comments

This is an excellent article. One should, however, note, that in contradistinction to Lt. Samuel Armstrong’s fowls, Joseph Plumb Martin’s repast on Dec. 18 consisted of “a gill of rice (four ounces) and a thimbleful of vinegar.” Officers, even lowly lieutenants, ate better than the enlisted men, having the liberty of the camp as well as orderlies; etc., who could do their foraging for them.

Also note that Gulph is the Dutch word for “gap.” In this case the gap in South Valley Ridge. If you wanted to get over or through this ridge to take your goods to the port of Philadelphia, you had find a gap in it. The area being first settled by the Dutch, they named it The Gulph accordingly. All roads led to the Gulph. Forty or so miles west along this same ridge there is Gap, Pennsylvania. Same ridge but the area was settled by English speakers. All roads there lead to The Gap and from thence to Newport, Delaware on the Christina River, a major port at this time.

An excellent lead up to the difficult days of Valley Forge. I always enjoy reading His Excellency Gen. George Washington’s words. They yet extoll his and his troops’ courage and determination in the face of overwhelming hardship for liberty and independence for his then nascent country.