The radeau (French, singular for “raft”) was co-opted for eighteenth century warfare on and along Lake George and Lake Champlain, to deal with the challenges of wilderness, inland waterways. The radeau’s design was unique, incorporating a pragmatic approach to the problem of transportation and concentration of ship-mounted artillery in a self-contained transport in shallow water. The radeau had much the appearance of a land tortoise. Ugly (apologies to the tortoise), slow, and ungainly, the radeau was a solution to how one concentrated and moved ordinance, slowly and carefully over water, in a backwater wilderness.

Radeaux (French, plural), though few in number, were locally constructed and used in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. The French name suggests that these “rafts” had commercial use throughout French-Canada in the years before the British conquest of 1760. Radeaux might be thought of as platforms that had application to land-fortress, siege warfare, where fortresses were built lake-side, such as at Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point on Lake Champlain. Flat bottomed, used as naval, floating gun-batteries, of simple construction, built from locally available oak used to frame pine planking, some had masts, but they were very poor sailing vessels.

Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen had taken Fort Ticonderoga from the British in May of 1775. Arnold then sailed a captured civilian sloop, re-named Liberty, to capture St. Johns (St. Jean Sur Richelieu, Quebec), a small dockyard-town on the Richelieu River, capturing also the King’s sloop Betsy, renamed Enterprise. The Americans beat a hasty retreat back to Lake Champlain, but had become the naval masters of Lake Champlain.

The British plan to drive the rebelling colonists from the region required assembling and building a suitable lake-navy[1] in Canada, to re-enter Lake Champlain via the Richelieu River. Once built and assembled it would clear American naval opposition, and British forces could concentrate on subduing strategic Fort Ticonderoga and American newly built fortifications across the narrows at Mount Independence. British General Sir Guy Carleton made good use of an attenuated supply chain back to England by arranging for prefabricated, small gun-boats to be delivered to Quebec City by June 1776. Further, he established Saint Johns on the Richelieu River as a shipyard for the necessary construction and refitting of his Lake Champlain fleet. Carleton planned that his Lake Champlain navy would employ locally constructed British men-of-wars, captained by well-seasoned Royal Navy officers, supplemented by numerous gunboats to do necessary in-close firing, manned principally by British and German artillerymen.

The Brunswick troops that had just disembarked at Quebec City on June 1, 1776, were quickly detailed to assist the British with construction, refitting, and preparation of the “Lake Champlain fleet.” Gen. Friedrich Riedesel noted in his Journal, “all those [German] soldiers who were carpenters by trade or knew how to work in wood, were sent to Chambly, Sorel, and St. John, to work on the vessels that were being constructed for the passage of Lake Champlain. These men received an extra shilling per day.”[2]

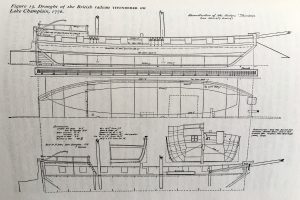

With the need for an artillery siege train to reduce fortifications, it was natural that the design for the radeau floating gun-battery would be reprised to again see service in the British Campaigns of 1776 and 1777. In addition to constructing five major ships, plus twenty-two gunboats, they built the Radeau Thunderer. Although of primitive design, Thunderer was innovative. The silhouette was not unlike the casemate ironclads of the American Civil War, with sloping sides protecting a main deck housing the guns, and a second deck above. Propelled reliably by oars rather than sails, its keel-less hulk “frustrated use of sail in any winds other than directly astern, or from the north. . . . When winds from any other direction materialized, the radeau essentially became immobile.”[3] As a floating gun-battery it provided much space for men and materials, eminently suitable for carrying extra ammunition and shot for the smaller, active gunboats often clustered around her.

It would become clear that not only would the Germans have extensive work in the construction and preparation of the Lake Champlain fleet, but ancillary preparatory work would also be required that was labor intensive and innovative. A road had to be constructed or improved between Chambly and St. Johns, Quebec. Specifically, four British man-o’-war vessels were built at Chambly, Quebec (on the Richelieu River), and a necessary bypass-road was constructed to avoid the Chambly rapids. These vessels were then transported overland on rollers, re-inserted into the Richelieu River, for their continued southward journey.[4] Lake Champlain, a freshwater lake 120 miles long, with maximum width of 12 miles, average depth of 60 feet, and maximum depth of 400 feet, was and still is, often tempestuous in the fall, but still needed to be traversed.

Additionally, the German infantry now had to be instructed on how to operate row-galleys and other water-craft to even get to their theatre of battle.[5] A typical bateau of the Burgoyne Campaign might carry eighteen to thirty-five men, depending upon what other baggage or stores it carried, and depending upon size could have as many as nine thwarts, or seats, five of which had two rowers on each end. Soldier-passengers took their turn at rowing, but might sleep sitting up when wedged between the rowers. Being a soldier did not entitle a man to a free ride over the waves of Lake Champlain. Nevertheless, Carleton’s 9,000 man land-force were poised at Saint Johns, ready to move south.

On September 19, 1776, Brunswick Dragoon Company Surgeon Julius F. Wasmus entered in his diary that he had the opportunity to visit St. Johns, where he observed the “Radeau or Floating Battery.” He noted that it had both a lower and upper deck, sporting six 24-pounders on the lower deck, and ten 12-pounders and two mortars on the upper deck.

On September 28, Capt. George Pausch of the Hessen-Hanau Artillery received orders to join the Radeau Thunderer, with members of his company. Captain Pausch served aboard the Thunderer only until October 1, but his short ship-board stint did not prevent him from making several pointed remarks. He noted he had to send some of his men back to Montreal because of over-crowding caused by the Thunderer primarily being used as a “magazine for provisions and munitions.” Additionally, Pausch noted the poor sailing qualities of the Thunderer when becalmed; the vessel had to be kedged ahead[6] by use of an anchor tied to a pulley, “pulled ahead by the troops.”[7]

The British had twenty-two or more gun-boats at the 1776 Battle of Valcour Island,[8] and used the Thunderer primarily to resupply them. “The gunboats would pull up on either side of the Thunderer, and ammunition would be hand carried from the hold of the Thunderer, across its deck, and handed to sailors on gun boats for carrying and storage in their ammunition bunker.”[9] This resupply work apparently consumed the whole of the night on October 11-12.[10] It appears that the Thunderer, though firing “some few Shots” in the Battle of Valcour Island, did not continue because she was out of range; she is not mentioned in battle accounts other than that of Lt. John Enys.[11]

The size of the Thunderer was massive, being 91.75 feet in length, 72 feet on the keel, 33.25 feet in breadth, and 6.66 feet deep in the hold,[12] with crew of 300.[13] Its size can be appreciated from a contemporaneously painted watercolor, A View of His Majesty’s Armed Vessels on Lake Champlain, in which the Thunderer is depicted as the tallest of the warships, among them the Carleton, Inflexible, Maria, and Convert.[14]

The Thunderer was so large that its interior deck could house the entire Royal Artillery headquarters attached to Burgoyne’s 1777 campaign,[15] carrying numerous sailors and artillerymen “along with staggering quantities of ordinance stores, and spare ammunition.”[16] Thunderer provided the kind of firepower in a single broadside equivalent to two-thirds the combined weight of projectiles of the entire American navy on Lake Champlain commanded by Benedict Arnold in 1776.[17]

Though apparently not directly involved in the Battle of Valcour Island, the Thunderer was a part of General Carleton’s force that chased the remnants of Benedict Arnold’s fleet. Carleton pursued the morning after the battle, across and up the Lake, and forced Arnold into a small bay where Arnold’s remaining craft were abandoned and burned. For the Thunderer lagging behind, the pursuit was almost her end, as she was confronted by heavy headwinds, where “her lee boards giving way which made her heel so much as to let some water into her lower part.”[18]

Because of the lateness of the year, Carleton withdrew his lake-navy and army to winter quarters in Canada, setting the stage for ministerial grumblings over his handling of the campaign, with Gen. John Burgoyne selected to become the new northern campaign commander in 1777. Burgoyne’s plan of invasion to the south necessitated gathering, refitting, and constructing more than 800 vessels that would be required to carry the combined British and German forces over Lake Champlain. Besides the larger capital ships, construction centered on smaller bateaux, canoes, pirogues,[19] and other small craft[20] to transport some 8,000 combatants and camp-followers.

A reference to the Thunderer appears in the Journal of the Brunswick Corps in America on April 4, 1777.[21] In discussing the construction of the fleet at St. Johns from the fall of 1776 through spring of 1777, the journal states:

For some considerable time now repair work on old boats and the building of some one-hundred new ones for the troops has been underway. . . . At St. Jean they have been working throughout the winter . . . and making some changes in the ships of the future campaign. The Radeau has also been changed completely because we no longer will have anything more to fear from the enemy ships. It now has eighteen cannons of twenty-four pounds up on the top deck which can be elevated at will. As a result they can be used against the batteries [at Forts Ticonderoga and Independence]. Formerly it had only six such twenty-four pounders below in the hull for destroying the enemy ships just above the water line . . . Captain Schencks, who won so much honor last year by building the Inflexible,[22] is director of all ship building. They have requested the model of a Braunschweiger flag from our Maj.-Gen. Riedesel and sent it to Capt. Schencks so that, it is believed, he can have a flag made for our nation.[23]

On June 13, Wasmus noted, “the radeau or Floating Battery which I described last year, is still here and has even grown taller by one story. It now transports 14, 24-pounders and several 12 pounder cannon; also 4 mortars. The 3-masted frigate Royal George has likewise been remodeled this spring and now carries 36 cannon. [In addition] there are 20 large bateaux (gunboats), each of them carrying 12 and 24 pound cannon which are destined for the Hesse-Hanau Constables [Artillery].”[24] The last sentence indicates the continuing reliance on German artillerists expected to play a significant naval combat-role in the gunboats supporting the 1777 campaign.

General Burgoyne’s lake-fleet now comprised: ships Royal George and Inflexible, the schooners Carleton and Maria, the Radeau Thunderer (possibly now namedBraunschweig), the gondola, Loyal Convert (also called Royal Convert), and some captured American vessels from 1776: the galley Washington (re-rigged as a brig), gondola Jersey, and cutter Lee.[25]

The British fleet assembled at Cumberland Head, near present-day Plattsburgh, New York, and moved south passing the Sable River. After staying several days at Ligonier’s Bay through June 23, they reached River Bouquet on the 24th, passed Split Rock on the 25th, with portions of the Army landing on the east side of lake Champlain at Button-Mould-Bay (now Button Bay) on the same date.

Reaching Crown Point Fort on June 26, which the Americans had deserted several days before, the Army remained four days and then advanced to Chimney Point, with the British right wing advancing along the west shore of Lake Champlain, while the Germans advanced along the eastern shore. The radeau was apparently the last ship in the naval convoy, “being used to carry ammunition and artillery.”[26] By July 2, Burgoyne’s army was within cannon-shot of Fort Ticonderoga’s guns.[27]

Historian Russell Bellico details the active but brief contribution of the radeau to the abandonment of Fort Ticonderoga by the Americans:

At noon on July 2 the American batteries opened fire on Fraser’s advance troops, but without proper sighting, the artillery barrage had little effect. Riedesel, with Colonel Heinrich Breymann and the German advance corps, moved forward to occupy a position to the north of Mount Independence. The fire resulted in a number of casualties on both sides during that day and the next. . . . The cannonading along the lake continued as the Radeau Thunderer was brought down to bombard the Americans. After the Radeau proved too unwieldly to maneuver, her heavy guns were dismounted on July 4 to be used as siege artillery on land.[28]

General Riedesel wrote, “On the 3rd [July], the enemy continued their cannonading; otherwise it was quiet on both sides. The floating battery arrived in the afternoon. A great deal was expected from this ram.”[29] However, “The heavy guns on the radeau or floating battery were removed, the latter not being able to approach the fort on account of its great draught and its general unwieldiness.”[30]

It is unclear whether the radeaudid fire her ordinance at Fort Ticonderoga or Fort Independence. Chaplain Philipp Theobold indicated, “the floating battery arrived here on 5 July, and 14 24-pounders and other war equipment were unloaded where the Yankees could see it. They set stumps below Ft. Independence on fire so the smoke could hide their fortifications . . . the Hanau artillery firing 60-some 24-lb cannonballs at them, but none arrived.”[31]

The Thunderer, possibly known to the Germans as the Braunschweig, “had sunk in late 1777.”[32] Her end was fairly remarkable as she was said to be last employed as troop transport for the seriously “wounded and sick from the Saratoga Battlefield, when she hit a rock near Windmill Point,”[33] near present-day Alburg, Vermont, the last American settlement before reaching Canada and the Richelieu River. No record survives as to whether any men were lost when the radeau sank. That she was transporting wounded British and Germans adds poignancy to her final voyage.

The radeau Thunderer was the fruition of an idea that transferred the methodology of land-based siege warfare, the construction of entrenched approaches, to naval warfare: a naval gun platform that could be maneuvered close to fortresses on inland waterways. The use of the Thunderer in 1776 and 1777 on Lake Champlain demonstrated that her size and load-carrying ability made her a formidable craft if given time and suitable wind and weather for positioning. Nevertheless, her performance in the heat of offensive operations such as Valcour Island, 1776, the chase of Benedict Arnold’s remnants down Lake Champlain, and the bombardment of Forts Ticonderoga and Independence in 1777, was disappointing.

Being slow and cumbersome, her last role was somewhat heroic, being possibly the first ship on Lake Champlain specifically designated for transport of battle casualties. Certainly this role was a worthwhile and memorable contribution to the conflict, even if inconsistent with her original planned use and ascribed moniker, Thunderer.

[1] Access to Lake Champlain via either the Richelieu River in the north or Lake George in the south required overland portages to avoid rapids or to overcome land separation. As a result, deep-water ships were precluded from access or use, and lake navies were made up of vessels locally constructed or capable of being disassembled and transported.

[2] William L. Stone, Memoirs, and Letters and Journals of Major General Riedesel, during his Residence in America (Albany: J. Munsell, 1868) 1: 51.

[3] Douglas R. Cubbison, The Artillery Never Gained More Honor: The British Artillery in the 1776 Valcour Island and Saratoga Campaigns (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2007), 72; Lt. John Enys of the British 29th Regiment was assigned to command a detachment of eighty-four from the Regiment, detailed to serve under the Artillery, and subsequently served aboard the Thundererat the Battle of Valcour Island. He noted that after passing Valcour Island searching for the Americans, they had to tack back upon discovering them, but the Thunderer “being a flat bottomed boat was totally useless, she being unable to work to Windward.” The American Journals of Lt. John Enys, Elizabeth Cometti, ed. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1976), 19.

[4] Stone, Major General Riedesel, 1: 54, 65.

[6] A ship may kedge ahead by using an anchor set in the lake floor, and then winching the anchor line to move the ship.

[7] Bruce E. Burgoyne, Georg Pausch’s Journal and Reports of the Campaign in America (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1996), 38-39.

[8] Russell P. Bellico, Sails and Steam in the Mountains: A Maritime and Military History of Lake George and Lake Champlain (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press,2001), 147.

[9] Douglas R. Cubbison, The American Northern Theatre Army in 1776: The Ruin and Reconstruction of the Continental Force(Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010), 241-242.

[11] The American Journals of Lieutenant John Enys, ed., Elizabeth Cometti, (Syracuse, NY: The Syracuse University Press, 1976), 19-20; The Scots Magazine, Vol. 38, 593-594, quoting a letter from Guy Carleton to Lord Germain, dated November 23, 1776, noted that the Thunderer was not able to keep up with the Mariaand Invinciblein their pursuit of Arnold.” books.google.com/books?idasr8Z1M8vxgC&pg=PA593&lpg=PA593&dq=description+of+ship+maria+on+lake+champlain& source=bl&ots=2gr8. Accessed Dec. 27, 2017.

[12] Bratten, The Gondola Philadelphia, 41.

[13] Helga Doblin and Mary C. Lynn, ed., An eyewitness account of the American Revolution and New England Life: The Journal of J.F. Wasmus, German company surgeon, 1776-1783 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990), 42 andn63.

[14] Watercolor by C. Randle, 1776, presently in possession of the Public Archives of Canada, as shown in Cometti, American Journals of Lt. John Enys, 19.

[15] Cubbison refers to the Thunderer as the floating “Park of Artillery,” housing both General Phillips and his staff as second in command to Burgoyne, and Major Williams’ artillery company. Cubbison, The Artillery Never Gained More Honor, 56.

[16] Douglas R. Cubbison, The American Northern Theatre Army in 1776, 232.

[17] Cubbison, The American Northern Theatre Army in 1776, 232-233.

[18] Cometti, American Journals of Lt. John Enys, 19.

[19] Pirogues are lengthy, flat-bottomed water-craft, sometimes constructed from tree trunks in simplest form, often used for baggage transport, but not stable in rough water.

[20] On July 7, 1776, the British frigate HMS Tartar arrived in Quebec carrying “ten light vessels of the kind suitable for the transportation of the troops across Lake Champlain.” Stone, Major General Riedesel, 1: 52.

[21] V.C. Hubbs, ed. and trans. “Journal of the Brunswick Corps in America under General von Riedesel,” Sources of American Independence; Selected Manuscripts from the Collections of the William L. Clements Library (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 230.

[22] In a display of naval engineering, HMS Inflexible had been built and disassembled at Quebec in 1776, transported on the Saint Lawrence River, then down the Richelieu River to St. Johns by boat, and re-assembled and commissioned at St. Johns. Carrying eighteen 12-pounders, it was a 180-ton sloop-of-war, and gained battle honors at the battle of Valcour Island.

[23] Hubbs, “Journal of the Brunswick Corps,” 249.

[24] Doblin and Lynn, Journal of J.F. Wasmus, 51. This entry shows that the Hesse-Hanau Artillery was extensively involved in the naval aspects of both Carleton’s 1776 campaign and Burgoyne’s 1777 campaign.

[25] Bellico, Sails and Steam in the Mountains, 165.

[26] Charlotte S.J. Epping, trans., Journal of Du Roi the elder, lieutenant and adjutant, in the service of the Duke of Brunswick, 1776-1778 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1911), 89.

[28] Bellico, Sails and Steam in the Mountains, 169.

[29] Stone, Major General Riedesel, 112.

[31] “Journal of the Hessen-Hanau Erbprinz Infantry Regiment June to August 1777 Kept by Chaplain Phillip Theobold,” Henry J. Retzer, trans., The Hessians: Journal of the Johannes Schwalm Historical Association Vol. 7, No. 1 (2001), 41-42.

2 Comments

Very informative and I appreciate the acknowledgement of the prior French colonial resources used to enhance British military aims. Also, a very accurate description of the Lake Champlain maritime conditions and features many of which still exist today.

Hi Ray: Merci and kind regards, a bientot, Mike Gadue.