Eighteen-year-old Andrew Sherburne’s younger brother, Samuel, guided Sherburne into a room away from the rest of the family to help wash and dress him. As he helped his older brother peel off his ragged, lice-infested clothing, Samuel glimpsed Sherburne’s emaciated body. Shocked, the younger boy fell back. “He having taken off my clothes and seen my bones projecting here and there, he was so astonished that his strength left him. He sat down on the verge of fainting, and could render me no further service.”[1]

Andrew Sherburne managed to wash off the filth that had accreted on his body during his imprisonment on board the British prison ship HMS Jersey, as well as the road dust accumulated during his journey home to New Hampshire. After washing, he pulled some clean clothes over his skeletal frame, the folds of fabric covering the sharp geometry of his protruding bones. He spoke briefly with his family and then went to bed. He barely sat up again for twenty days.

It was spring of 1783 when Sherburne was released from the Jersey and embarked on his journey home. Although plagued with crippling diarrhea the whole way and so weak that he could barely pass over a door step without help, he made it home safely. Clean and comfortable for the first time in many months, Sherburne retreated to his bed, his ravaged physique testament to the starvation and sickness he had suffered while a prisoner.

At age eighteen, he was already a seasoned sailor, having signed up for his first cruise at thirteen. He had been serving on the privateer Scorpion in the autumn of 1782 when captured by the British Royal Navy. He and the rest of the crew were taken as prisoners to New York and confined on the Jersey. By the time of Sherburne’s imprisonment in 1782, the Jersey was already notorious for its shocking filth, rampant disease and the high mortality of its prisoners.

First used as a hospital ship, the Jersey was hulked and converted into a prison ship for American sailors about 1779. In being repurposed from a warship to a prison, the Jersey had been stripped of almost all sails, spars and rigging. “Nothing remained but an old, unsightly, rotten hulk. Her dark and filthy external appearance perfectly corresponded with the death and despair that reigned within.”[2] The Jersey’s portholes had all been sealed shut. Iron-barred breathing holes were drilled the length of the ship about ten feet apart.[3] The ship, blackened with filth and teeming with disease, was moored in the shallows and mudflats of Wallabout Bay, off Brooklyn, New York.

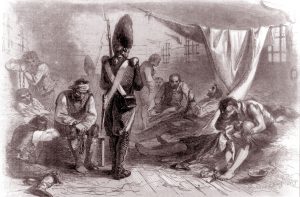

Long after the war was over, many men wrote memoirs detailing their experiences as prisoners on board the Jersey. Ebenezer Fox, who had been imprisoned on the Jersey as a seventeen-year-old in the late spring of 1781, recounted that the prisoners were “a motley crew, covered with rags and filth; visages pallid with disease, emaciated with hunger and anxiety, and retaining hardly a trace of their original appearance.”[4]

Capt. Alexander Coffin, who held the dubious distinction of having been imprisoned on the Jersey not only once but twice (once in 1781 and again in 1782) recalled that theprisoners subsisted in “the most deplorable situation, mere walking skeletons, without money, and scarcely clothes to cover their nakedness, and overrun with lice from head to feet.”[5]

In describing their captivity, the men attested to a litany of horrors. Every day at dusk, the prisoners were forced below deck, shuffling like wraiths into the locked hold of the ship to pass the overnight hours. In the summer, men suffocated—sometimes to death—in the hellish, fetid hold. In the winter, men awoke to three or four inches of snow upon their blankets[6] or watched their limbs slowly blacken with deadly frostbite. The men also suffered the never-ending torment of lice infesting their hair, clothes, and bedding.

The specter of death was inescapable. Wracked by the uncontrollable evacuations of dysentery, the derangement of yellow fever and the oozing pustules of smallpox, the prisoners suffered violently on the Jersey. Disease—potent and brutal—cut down the men with indiscriminate efficacy. Prisoners died in untold numbers.[7]

Among these four mortal terrors—suffocating heat, frigid cold, the maddening itch of vermin and the monstrous ravages of disease—should be added one more: starvation.

Twenty-five years after the end of his second imprisonment, Captain Coffin asserted that, “I can safely aver, that both the times I was confined on board the prison ships, there never were provisions served out to the prisoners that would have been eatable by men that were not literally in a starving situation.”[8]

Provisions on the Jersey consisted of meager servings of rotten meat, wormy bread and foul water—barely enough for a man to subsist on.[9] But in an effort to satisfy their constant gnawing hunger and stave off starvation as long as possible, the prisoners ate what they could—no matter how rotten, rancid or spoiled.

Fox noted that “The bread was mouldy, and filled with worms. It required considerable rapping upon the deck before the worms could be dislodged from their lurking places in a biscuit.”[10] According to Sherburne, provisions consisted of “worm eaten ship bread and salt beef. . . . The bread had been so eaten by weevils, that one might easily crush it in the hand and blow it away.”[11]

Some men had devised a solution for the problem of crumbling bread. Concurring that “the particles of the biscuit . . . so riddled by the worms, had lost all their attraction of cohesion,” Fox undertook to use spoiled butter as a glue to hold the bread together. Of the butter, Fox noted, “Had it not been for its adhesive properties to retain together the particles of the biscuit, we should have considered it no desirable addition to our viands.”[12]

Thomas Andros admitted, “our bread was bad in the superlative degree. I do not recollect seeing any which was not full of living vermin, but eat it, worms and all, we must, or starve.”[13]

Morsels of beef or pork were also provided but were so rancid that Fox concluded that “one would have judged from its motley hues, exhibiting the consistence and appearance of variegated fancy soap, that it was the flesh of the porpoise or sea-hog, and had been an inhabitant of the ocean rather than of the sty.”[14]

Fox also offered piquant commentary on not just the fare but the methods of preparation. “The cooking for the prisoners was done in a great copper vessel . . . divided into two compartments by a partition. In one of these, the peas and oat-meal were boiled; this was done in fresh water:”[15] He notes, “the peas were generally damaged, and . . . were about as indigestible as grape-shot. . . . The flour and the oat-meal were often sour, and when the suet was mixed with it, we should have considered it a blessing to have been destitute of the sense of smelling before we admitted it into our mouths.”[16]

In the large copper pot’s other compartment, the meat was boiled in sea water scooped up from alongside the ship.[17] Meat boiled in sea water does not sound particularly appetizing but it takes on an even more disturbing dimension when Fox reveals, “The Jersey . . . was imbedded in the mud. . . . All the filth that accumulated among upwards of a thousand men was daily thrown overboard, and would remain there till carried away by the tide.”[18] Working parties were employed each morning on the Jersey to empty the tubs of human waste which had accumulated overnight below deck. The contents of those tubs were dumped over the side of the ship, contaminating the water below. “And in this water our meat was boiled.”[19]

Also in uncomfortable proximity to the prison ship was a sand bank where prisoners who died were buried. It is unclear exactly how many Americans who perished aboard the Jersey were buried on the shore of Wallabout Bay. But every morning, after the first rays of sunlight filtered into the hold and the hatches were sprung, it would be revealed that some prisoners had died in the night. And so the daily removal of the bodies of those unfortunate men would commence.

Capt. Thomas Dring, who was imprisoned on the Jersey in 1782, recalled that the bodies of the men who had died were brought above deck and laid across the gratings. One at a time, the corpses would be placed on a long plank strapped on each end with rope. The board was used, Captain Dring observed, because the bodies “might be yet too warm or not stiff enough to send into the boat by a single strap.”[20] Christopher Vail, however, who was confined on the Jersey in 1781, remembered that the bodies were “lowered down the ships sides by a rope round them in the same manner as tho’ they were beasts.”[21]

The bodies were lowered by rope into a waiting boat and then ferried “in heaps”[22] to the shore of the Wallabout, where they were “hove out the boat on the wharf.”[23] The bodies were then loaded into wheelbarrows[24] and transported to the sandbank—or, as the sandbank started to overflow with corpses, to other adjacent areas with greater capacity to receive the dead. A shallow hole was dug into which the bodies were “all hove in together” and hastily interred under a few shovelfuls of sand. “Many bodies would, in a few days after this mockery of a burial, be exposed nearly bare by the action of the elements.”[25] Sometimes, due to weather and tides, they would even be washed out of their graves.[26]

In a desperate bid to supplement their scant, rotten provisions, some starving prisoners sought sustenance from the hogs’ trough, or even consumed lice. According to Captain Coffin, hogs were kept on the ship for the officers’ use. “I have seen the prisoners watch an opportunity, and with a tin pot steal the bran from the hogs’ trough, and go into the galley . . . and boil it over the fire, and eat it, as you, Sir, would eat of good soup when hungry.”[27]

Young Christopher Hawkins, who was about seventeen years old while on the Jersey, recalled that, “I one day observed a prisoner on the fore-castle of the ship, with his shirt in his hands, having stripped it from his body and deliberately picking the vermin from the plaits of said shirt, and putting them into his mouth. . . . He had been so sparingly fed that he was nearly a skeleton, and all but in a state of nudity.”[28]

Some desperate prisoners would compete in a hellish contest for food, sometimes at risk of injury.Thomas Andros remembered, “Once or twice, by the order of a stranger on the quarter deck, a bag of apples were hurled promiscuously into the midst of hundreds of prisoners crowded together as thick as they could stand, and life and limbs were endangered by the scramble. This instead of compassion was a cruel sport. When I saw it about to commence, I fled to the most distant part of the ship.”[29]

A popular myth related to the prison ships is that a woman from New York named Elizabeth Burgin boarded the ships to deliver food to the prisoners, and even to orchestrate a massive escape. It is documented that Elizabeth Burgin did indeed provide significant assistance to numerous American prisoners—somehow—during the war. However, none of the several prisoners’ narratives consulted for this article mention women on board the prison ships or an escape en masse.[30] No evidence has yet been discovered which definitively places Elizabeth Burgin on board any prison ships.

At least one woman, however, did come close enough to the Jersey to interact with the prisoners. Small boats called “bumboats” would frequently come alongside the prison ships to sell food and personal care items to prisoners who could afford to pay for those items. According to Captain Dring, permission had been granted for

a boat to come alongside of the Jersey. . . . This boat was called the bumboat, and the trade [was] conducted by a very corpulent old woman whom the prisoners called Dame Grant. . . . She came from New York every other day with her well selected articles of trade such as sugar, tea, soft bread, fruit, etc., all of which was ready in parcels done up in paper from one pound to one ounce, the price already affixed on them, from which there was no deviation. . . . The old lady sat in the stern sheets of the boat (which her bulk completely filled). She had with her two boys to row the boat and hand us the article we wanted, first receiving the money for it.[31]

In addition to food, the men anxiously awaited Dame Grant’s deliveries of “pipes, tobacco, snuff, thread, needles, paper, hair combs, and many other things of which we stood in need.”[32] With palpable discomfiture, Captain Dring recalled purchasing items from Dame Grant in the full view of men without money.

While making our purchase, it was lamentable to see hundreds of poor, starving wretches looking over the side into the boat, viewing with hankering the contents which they had it not in their power to purchase. . . . There was none among us who had the means of supplying their wants even if we had the disposition to do it. I never seemed to enjoy what I had procured for my own comfort from this boat on this very account, seeing so many needy [men] gazing at the purchase made, who seemed almost dying for the want of it.[33]

Sherburne, though confined on the Jersey at a different time than Captain Dring, also noted that men with money could purchase extra food from vendors. These servings of fresh food must have proved a welcome addition to the prisoners’ regular allowance in both taste and nutritive value. “As long as one’s money lasted, he could have better fare. . . . There were large quantities of provisions brought from the city and sold to the prisoners . . . livers and lights [lungs] of sheep, cattle, etc., were well boiled, chopped fine, seasoned with pepper and salt, and filled into the small intestines of those animals . . . most of my money went for those meat puddings, and for bread.”[34]

Unfortunately for Captain Dring and the other men, the cornucopia of goods flowing from Dame Grant’s bumboat was not to last forever. She fell ill with a fever—which Captain Dring believed she contracted from the prisoners—and died.[35]

Even years after captivity, innocuous moments of everyday life could spark recollections of the Jersey and prompt memories to arise unbidden in the minds of former prisoners. “Many times since, when I have seen in the country, a large kettle of potatoes and pumpkins steaming over the fire to satisfy the appetites of a farmer’s swine, I have thought of our destitute and starved condition, and what a luxury we should have considered the contents of that kettle.”[36]

Even the simple act of sipping water demonstrated the lasting imprint of imprisonment that the men carried with them during the following decades. Every night, before being locked in the hold for the night, Sherburne had filled a tin cup with water.[37] In order to make the water last through the night, he would limit the number of sips he took by counting each one. “I was under the necessity of using the strictest economy with my cup of water; restricting myself to drink such a number of swallows at a time, and make them very small: my thirst was so extreme that I would sometimes overrun my number. I became so habituated to number my swallows, that for years afterwards I continued the habit, and even to this day, I frequently involuntarily number my swallows.”[38] Andrew Sherburne counted his sips for half a century.

Though most men fortunate enough to survive the Jersey were eventually freed in body, the deprivations they endured as prisoners were indelibly seared into the psyches of some. Even fifty years of living and intervening experiences could not undo the survival strategies the men developed in response to the conditions aboard the Jersey, nor erase the scars of starvation.Decades after eating their last meal on board, the taste of the Jersey lingered.

(Listen to the author discuss this topic on Dispatches, the podcast of the Journal of the American Revolution.)

[1]Andrew Sherburne, Memoirs of Andrew Sherburne: A Pensioner of the Navy of the Revolution (Providence: Brown, 1831), 126, books.google.com/books?id=l906AQAAIAAJ&dq=andrew%20sherburne%20prisoner&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[2]Thomas Andros, The Old Jersey Captive: Or a Narrative of the Captivity of Thomas Andros On Board The Old Jersey Prison Ship At New York, 1781 (Boston: William Peirce, 1833), 8, books.google.com/books?id=sTZPAAAAYAAJ&dq=Narrative%20of%20Thomas%20Andros%20on%20board%20the%20Jersey%20Prison%20Ship&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[3]Thomas Dring, Recollections of Life on the Prison Ship Jersey, ed. David Swain (Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2010), 8.

[4]Ebenezer Fox, The Adventures of Ebenezer Fox, in the Revolutionary War (Boston: Charles Fox, 1847), 99-100,archive.org/details/adventuresebene00foxgoog/page/n10.

[5]Danske Dandridge, “The Narrative of Captain Alexander Coffin,” in American Prisoners of the Revolution (Charlottesville: The Michie Company, Printers, 1911), 313, books.google.com/books?id=vy5ozMZfT28C&dq=American%20Prisoners%20of%20the%20Revolution%20By%20Danske%20Dandridge&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[7]It is commonly written that 11,500 American prisoners died on the Jersey prison ship. However, the provenance of this figure is somewhat murky and this figure might be unreliable. For more, see Dring, Recollections, 6.

[8]Dandridge, “The Narrative of Captain Alexander Coffin,”314.

[9]Prisoners were supposed to receive two-thirds the allowance of food that Royal Navy sailors were served, but it is unclear if the prisoners on the Jerseyreceived that much. And, the food that the prisoners did receive was almost always spoiled to the point of being nearly inedible. Some men suspected that they were being served the rancid, inedible rations condemned by the Royal Navy. See Dring, Recollections, 30-31.

[11]Sherburne, Memoirs, 110-111.

[13]Andros, The Old Jersey Captive, 17.

[21]John O. Sands, “Christopher Vail, Soldier and Seaman in the American Revolution,” Winterthur Portfolio, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. vol. 11 (1976): 71,www.jstor.org/stable/1180590.

[26]John Warner Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New York (New York: Tuttle, 1842), 222, books.google.com/books?id=2ZyGfk7FqlYC&dq=remsen%20prison%20ship&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

[27]Dandridge, “The Narrative of Captain Alexander Coffin,”314.

[28]Christopher Hawkins, The Adventures of Christopher Hawkins (New York: Privately Printed, 1864), 71-72, archive.org/details/adventureschris00bushgoog/page/n6.

[29]Andros, The Old Jersey Captive, 9.

[30]One exception is an unnamed woman who boarded a ship to exhort the prisoners to write a petition to General Washington regarding the prison conditions, which she would carry to the general. See Ichabod Perry, Reminiscences of the Revolution (Lima, New York: Ska-Hage-Ga-O Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution, 1915), 17, archive.org/details/reminiscencesofr00perr/page/16.

[31]Dring, Recollections, 61-62.

[33]Dring, Recollections, 62. Capt. Alexander Coffin claims he had about twenty dollars on him at the time of his capture. See Dandridge, “The Narrative of Captain Alexander Coffin,”315.

4 Comments

Very informative! My 4th great grandfather, Silas Talbot, was imprisoned aboard the Jersey for a period of time and survived it. I’m curious to know what became of the hulk, and if any remnants or artifacts survive.

Hi Peter, according to this article from 1902, the Jersey was discovered sunk in the mud during construction in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Supposedly the hull was discovered under “2 fathoms of mud”. Here’s a clipping of a news article: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/8217169/prison_ship_jersey_which_was_used/ I haven’t done any research on what happened to the Jersey beyond this but I understand it was possibly burnt and abandoned.

Something I found interesting is that Captain Thomas Dring in his narrative (edited by David Swain, published by Westholme Publishing) mentioned that the men had carved their names into the wooden planks between decks, and that there was barely a spot that didn’t have a man’s name or initials carved into it.

Fascinating account, Katie, thank you! Happy to be born when I was and grateful to these mentally strong men for enduring such horrific conditions in order to help secure our freedom!

My fifth great-grandfather, Daniel Mosher, endured 18 months aboard the Old Jersey before being released and living to the ripe age of 94. Even with the benefit of your detailed article, it is impossible to fathom the despair he and the rest of the men must have felt while confined to that wretched ark.

Thank you for your research and bringing to life for me the death that surrounded my forebear.