“There has been hell to pay in Philadelphia,” exclaimed Samuel Shaw, referring to the Fort Wilson Riot of October 4, 1779 in a letter to Winthrop Sargent.[1] The riot was the culmination of three years of factional political tension within the city of Philadelphia. Members of the city’s “lower sort,” nominally backed by politically powerful men of middling means, took to the streets to protest high prices and unfair treatment from the political elite.[2] Although they marched without a clear plan of action, the house of James Wilson, an esteemed lawyer and signer of the Declaration of Independence, became the target of their rage. Inside the house, remembered in history as “Fort Wilson,” Wilson joined with other leading citizens to combat the crowd’s advance. Ultimately, the riot resulted in the deaths of one person in the house and several members of the crowd. Following the event, the political leaders of the city, men of moderate station who had risen to prominence in the turmoil of the 1760s and 1770s, withdrew their support from the crowd. The escalation of heated rhetoric into actual skirmishing stunned the residents of Philadelphia; the resulting change in attitude among “the middle sort” would have serious implications on the political trajectory of the city.

The events of Fort Wilson were chaotic and confusing even to immediate participants. Nevertheless, it remains an important and indeed transformative event in the development of a republican political culture within Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. During the colonial and early revolutionary period, extralegal political participation was a critical part of political events in the city. As the Revolution wore on, actors of all ideologies and backgrounds, including the crowd, began to debate and create new republican theories. After the riot, however, the voice and power of the crowd noticeably diminished as the middling sort moved toward the political center. A consensus republican vision emerged that incorporated very few suggestions from those who expressed their politics “outside of doors.” Through the rejection of the actions of the lower sort by the politically powerful, important new boundaries were placed on acceptable political participation following the Revolution.

Prior to 1760, Pennsylvania’s colonial government essentially functioned as an elected oligarchy. Political power was concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy families connected to the Penn family. By 1776, however, political participation had expanded dramatically, making Pennsylvania one of the most democratic states in history.[3] This dramatic change was the work of two groups that operated in concert: revolutionary committees and the militia. Throughout the late 1760s and 1770s, both groups sought to undermine the official government. Their actions fit a well-established pattern of citizen participation during the colonial period. During this time, citizens often intervened in politics when governments failed to meet their obligations or when repeated petitions of grievances to a government were ignored.[4]

The partnership between the committees and the militia brought together the middling and lower sorts, both of whom had been shut out of power by the closed nature of proprietary rule. The revolutionary atmosphere provided ambitious men, including lawyer Joseph Reed and Timothy Matlack—a failed brewer—the chance to participate in politics and raise their station and influence. Increasingly, the committees took over the functions of government from the Pennsylvania colonial assembly and fully assumed the reins of power by 1776.[5] The militia, dominated by the lower sort, provided the muscle needed to complete this process. Because of their power to influence events, the crowd-dominated militia was an important player in the political scene of the early 1770s, which ensured that the voice of the crowd was heard.[6] By working together, the middling and lower sort were able to advance the Revolution and positioned themselves to set the tone for Pennsylvania’s first foray into republican formation: the State Constitution of 1776.

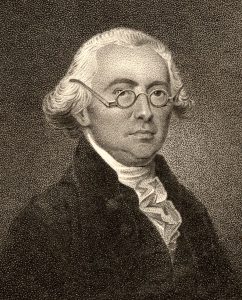

Produced in the immediate aftermath of the Declaration of Independence, Pennsylvania’s first Constitution, ratified on September 28, 1776, fully embodied the leveling impulses that motivated the lower sort during the American Revolution. Provisions such as near universal suffrage for white males, a unicameral legislature, and an executive council rather than a solitary executive, decentralized political power and increased the number of hands in which power was held.[7] Almost immediately, however, the controversial document led to a split in Pennsylvania’s Whig coalition. More genteel Whigs, including Wilson, Morris, and men like Dr. Benjamin Rush, balked at the lack of traditional safeguards of representative governments, including mixed government and a rudimentary system of checks and balances.[8] In a letter to the Pennsylvania Gazette, Wilson criticized the State Constitution for introducing tyranny into government because of its lack of balance.[9] He argued that monarchy was not the only form of ineffective government. Above all, however, these men feared the influence of the crowd in government. Thomas Smith, a delegate to Pennsylvania’s Constitutional Convention, argued that the State Constitution operated on the principle “that any man, even the most illiterate, is as capable of any office as a person who has had the benefit of education.”[10] Rush succinctly vocalized the fears these men felt, stating in a letter to Charles Lee written after the Fort Wilson Riot that, under the State Constitution, “All of our laws breathe the spirit of town meetings and porter shops.”[11] Fierce in their opposition, they faced sharp rebukes from the supporters of the State Constitution who praised the fact that it offered checks on power from below, rather than the elite checks from above that men like Wilson wanted.[12]

Eventually, debate over the new State Constitution led to the formation of two opposing political societies. The Republican Society, formed by those who opposed the Constitution, operated as a kind of opposition party to the pro-Constitution faction that dominated the Pennsylvania assembly. Soon after, the pro-Constitution faction created their own society, aptly named the Constitutional Society, to oppose the Republicans. Members of the Republican Society were primarily wealthy businessmen with incomes that were often double the average income of inhabitants of Philadelphia. The Constitutional Society was formed by the middling class and supported by working men and the crowd. Generally, the Republicans were more cosmopolitan and better educated than the Constitutionalists. They also had more experience in national and international affairs.[13] For the next decade, Philadelphia politics would hinge on the interactions and power struggles between these two factions as they attempted to sell their program to the citizens of the city.

By 1779, less than a year after the British had ended their eight-month occupation of the city, Philadelphia was crippled by shortages of essential products. Political debates increasingly centered around how to lower prices and effectively allocate these goods.[14] Societal elites, political stakeholders, and the crowd took sides according to their beliefs regarding the relationship between the economy, the government, and the public good. The Constitutionalist faction, and especially their working-class supporters, were driven by a devotion to the “moral economy.” They argued that merchants, laborers, and all other members of society needed to look beyond their own narrow private interests to better serve the greater public interest of the republic.[15] The view of private virtue and the duties of citizenship held by members of the Republican Society differed sharply from the “moral economy” envisioned by the lower sort. According to the Republicans, merchants best served the public interest through their own private actions which in turn created wealth for all. Harming merchants by over-controlling prices thus harmed the community by hindering their ability to create wealth. Furthermore, they fundamentally disagreed with the lower sort over the main goals of a republic. Whereas the lower sort extended a “leveling spirit” to their conception of republicanism and advocated for common sacrifice for common gain, merchants looked to the republic for one interest in particular: the protection of property rights.[16]

The first sign of how serious the problem with prices would become came in the form of an anonymous letter published in the Pennsylvania Packet in December 1778 titled “A Hint.” Directed to the elected government it read in part: “Hunger will break through stone walls, and the resentment excited by it may end in your destruction.”[17] By late May 1779, the desperation and resentment that the author of “A Hint” predicted became evident in the city’s masses. The discord in the city made many citizens “apprehensive of a mob rising” according to Quaker diarist Elizabeth Drinker. Two days after that observation, she reported the posting of “threatening handbills . . . with a view to lower prices” in the city. The broadside she references, titled “For Our Country’s Good!” and signed “Come on Cooly,” appeared on the night of May 23. It highlighted the plight of the lower classes in Philadelphia and warned that “We have turned out against the enemy and we will not be eaten up by monopolizers and forestallers.” Once again, the lower classes had surveyed the political and economic landscapes and unabashedly warned the ruling powers that they would not hesitate to take matters into their own hands should their needs go unmet.[18]

During the summer of 1779, an extralegal committee was formed to combat increasing prices and diffuse the tension between the lower sort and other citizens of the city. Warning the city that the “rage for raising prices will, unless it be put a stop to, become the ruin both of those who contrived it, and those who follow it,” the committee proposed several measures to reduce prices month by month until “the price of such goods was worth or sold for in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy-four.” Furthermore, it appealed to those with the means to influence prices to heed their suggestions, for in the view of the committee, lowering prices and protecting against the depreciation of currency would serve the economic interests of all citizens.[19]

To many of the merchants of Philadelphia, price control represented a dangerous threat to individual property rights and their own republican vision. “The limitations of prices,” they wrote, “is in the principle unjust, because it invades the laws of property, by compelling a person to accept of less in exchange for his goods than he could otherwise obtain, and therefore acts as a tax upon one part of the community only.” In their arguments, the Republican merchants elevated freedom of the market to the level of a natural law and in the process, directly contradicted their opponent’s conception of Republican responsibilities and ideals. Firm in this alternate vision, the merchants determinedly resisted the efforts of the committee. Unwilling to further erode property rights and faced with opposition from those who could best address the rise in prices, the middling leaders of the constitutional government and the committee ultimately failed to solve the problem. By September 24, they admitted defeat, declaring that there was “no eligible method but to endeavor to keep matters as they were, until the meeting of the Assembly, before whom we have laid the business.” After working for most of the summer to no effect, the committee disbanded and prices remained high.[20]

At the end of August, nearly a month before the committee officially suspended business, a second broadside related to the matter of prices appeared. Headed “Gentlemen and Fellow Citizens,” it was signed “Come on Warmly,” which illustrated that tempers had escalated since the May broadside signed “Come on Cooly.” It called for the militia and common people to defend the committee and punish those that were keeping prices high and working against the State Constitution. On September 27, only three days after the committee abandoned their mission, militia members fulfilled the call to action when they assembled at Burn’s Tavern about ten blocks from the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) to begin plotting a response to what they viewed as a failure of government. Though their goals and exact motives are unclear, they remained dissatisfied with the price of goods and also sought to punish the men, women, and children still in the city who possessed Tory sympathies. Before disbanding, they resolved to meet again and entreated respectable men such as Charles Willson Peale to join and lead them.[21]

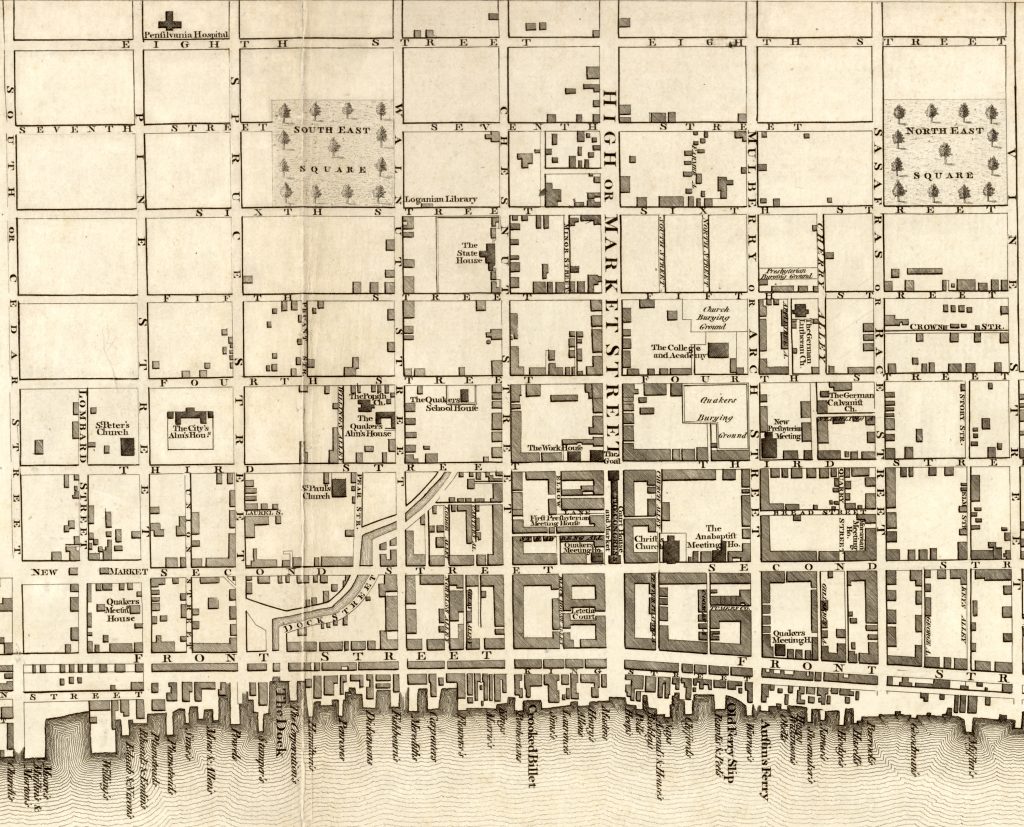

The militia next met on the morning of October 4. According to their broadsides, they planned to drive a group of prominent Tories from the city. John Drinker (Elizabeth Drinker’s husband), Buckridge Sims, and Thomas Story were singled out for exile in the publication. The meeting began earnestly with militia members giving speeches and listening to responses from Charles Willson Peale and the other Constitutionalists called to the meeting who each attempted to calm the crowd. When their attempts at forcing reconciliation failed, Peale and the other leading men left the tavern and separated themselves from the actions that would soon occur.[22] By noon, the crowd had taken to the street and apprehended their first victim, John Drinker. He was taken while leaving the Quaker Meeting House on Arch Street, brought to his home to finish his lunch and then paraded back through the streets. Soon, the two other men whose names had appeared on the broadside, as well as a man named Matthew Johns, were arrested by the crowd and brought back to Burn’s Tavern.[23]

At around three o’clock in the afternoon, the militia began to march again. Along with the men they had detained, they advanced towards the Delaware River and the home of James Wilson. It is unclear whether the crowd intended to attack Wilson at this point. Accounts that claim cries were let out to “get Wilson,” or to attack the Republicans are usually secondhand or otherwise discreditable, making it unlikely that the marchers had specific plans. Viewing the crowd through the lens of the colonial political practices of the lower sort further bolsters the defense that they were political actors with specific discreet aims rather than an unruly drunken rabble. Like earlier colonial protestors, those that marched on October 4 were seeking to correct what they perceived as failures in the laws and government of the city and state. They marched believing that their political partners, the middling leaders of the Constitutional Society, would share this conception of republicanism and back their actions.

As the militia advanced in the general direction of Wilson’s house, Wilson and his Republican compatriots began to fear that “the mob” would soon turn on them. This fear explains the defensive posturing of the Republicans, regardless of the actual motives or intentions of the crowd. Several eye-witness accounts note that the gentlemen began to assemble near the City Tavern and were drilled by veteran military officers. When the militia approached, the gentlemen promptly fell back to the “fort” to prepare their defense. During this time, several citizens attempted to turn back the militia or otherwise defuse the situation. Allen McLane wrote that he and his companions met the militia officer leading the crowd and expressed the dangers of moving against “Fort Wilson.” The officer countered that “they had no intention to meddle with Mr. Wilson or his house; their object was to support the constitution, the laws and the Committee of Trade.” As the crowd approached the house, several other men attempted to rouse Joseph Reed to defuse the situation by reminding him that he was partially to blame for what was to occur because of the ties between the Reed-backed Constitutional Society and the crowd.

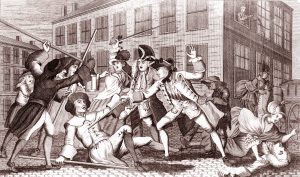

As the militia reached Wilson’s house, the tensions that had been building in Philadelphia over the previous three years exploded. The crowd began to move past the “fort,” giving three cheers as they did, when a gentleman, George Campbell, emerged from a second-floor window of the house. Sources differ regarding what happened next. Some say Campbell fired his pistol at the crowd. Others say that Campbell merely shouted at the crowd and that the first shots came from the street. After that first shot was fired, bedlam ensued. Campbell was soon shot and killed and was to be the only casualty from inside Fort Wilson. A party of militia attempted to force entry through the back door of the house but were driven back by hand-to-hand fighting. The militia continued their attempts to breach the defenses and even began to fire a cannon on the house when Reed and a detachment of the City Light Cavalry appeared and broke the crowd using the flats of their sabers. They also arrested a number of marchers and brought them to the city jail. No men from the house were arrested. Instead, according to McLane, “Wilson and his friends in the house sallied out” onto the street, giving hearty cheers to celebrate their victories.

Casualty estimates of the riot vary. Campbell is confirmed to be the only person to die inside of the house. Regarding the crowd, sources disagree but are usually centered near five dead and fourteen wounded. Despite Reed’s efforts to quell the uprising, tensions ran high in the city and prominent citizens began to flee to the countryside. Samuel Rowland Fisher, imprisoned by the city government because of his Quaker beliefs, recorded the air of confusion in the city and shared that the marchers who had been jailed criticized Joseph Reed heavily, foreshadowing the breaks in the radical coalition that were to occur.[24] Reed would be aware, Fisher wrote, that “this late affair had much shaken his authority in the minds of the people.” Samuel Patterson confirmed Fisher’s analysis that the city was still very much gripped by fear and confusion. “It is not over,” he wrote, “they will have blood for blood.”[25] Fort Wilson was an escalation of violence and rhetoric to levels previously unseen in the city and Philadelphia’s inhabitants feared what could happen as a result.

Immediately following the riot, Reed and other government officials worked assiduously to keep peace. Faced with pressure from the militia, Timothy Matlack ordered the men who were jailed to be released, likely to avoid the jail being stormed by the crowd, which would have further undermined civil authority. Reed personally rode out to Germantown the day after the battle to calm a second group that had risen to support their compatriots inside of the city. These actions successfully lowered tensions, and by October 7, Elizabeth Drinker recorded the “quietness” of the day, suggesting that order had finally been restored. Even so, Benjamin Rush, while thankful that no further violence had erupted, told John Adams on October 12 that, “Every face [in the city] wears the marks of fear and dejection.”[26]

In the short term, the Constitutionalist government supported the crowd. However, they acted out of a desire to mollify the tempers of the lower sort rather than acting in support of the programs and positions of the crowd. On October 9, the Constitutional Society announced that they would be obtaining a subscription for “the Support of the necessitous Families of those unfortunate Men, who were killed and wounded on the 4th Instant.” On the 12th, they announced their plans to address the conflict by enabling the Supreme Executive Council and courts to apprehend and prosecute those involved in the affair. Though they collected testimony, no one was permanently imprisoned. By March 1780, a general pardon had been passed providing an end to the immediate business of the riot.

Additionally, the Assembly released a proposed slate of bills to address the grievances that had caused the crowd to march in the first place. They increased fines for those that did not turn out for militia duty, promised to more strictly engage monopolizers and price aggrandizers, and released a plan for ensuring that poor and needy families would be provided essential goods throughout the coming winter. However, these bills did nothing to address the deep structural differences between the political elites and the crowd.[27]

After calming the crowd with these early measures, the Constitutionalists broke with their former allies and began to critique the conduct of the crowd while increasingly aligning with their former adversaries, of the Republican Society. Constitutionalists such as Joseph Reed began to speak out against price control and incorporated semi-sacred property rights into their republican vision. In his official statement to the Assembly regarding the matter, Reed blamed the riot on “casual overflowings of liberty [rather] than proceeding from avowed licentiousness or contempt of public authority.” He then expressed his hope that “it will be the last instance where individuals will take the vindication of their real or apprehended injuries into their own hands.” Reed’s statement, which dripped with condescension, conveys that moving forward, his republican visions would more closely align with the Republican Society’s. Prompted by the Fort Wilson Riot, Reed broke with the crowd.

Thomas Paine, while still offering tepid support for the lower sort, questioned their judgment, writing that “the difficulty of attempting such a measure, the hazard of executing it, and the consequences which might probably ensue, without first obtaining . . . consent were matters which do not always accompany an excess of zeal.” Paine admired the ardent spirit of the marchers but faulted them for overstepping their bounds and denied their right to participate in politics without “consent.” Their admirable spirit, then, would only be utilized as the political elite saw fit. Such writings convey how the Fort Wilson Riot impacted republican formation within the city and by extension the state. The middling political class expressed their distaste for the violent and extralegal methods of the lower sort and began to bound legitimate political participation within the political world that they had built. Participation outside that world or attempts to overthrow it were not accepted by the Constitutionalists moving forward.[28]

Men like Joseph Reed had gained prominence through similar demonstrations against imperial officials. However, they were now several years removed from gaining power, and they began to reject the very tactics they themselves had used. Although seemingly contradictory, this change illustrates the differences between the republican conceptions of the middling and lower sort. These differences had existed from the very beginning of the Revolution, but, for the sake of political necessity and expediency, were not brought to the surface until after the Fort Wilson Riot. They developed mainly because of the different ways that the two groups experienced and constructed republican visions. Similar to the gentry, classic political treatises and writings shaped the middling sort’s republican visions. These treatises argued that republicanism ought to provide two things: a government that expressed and served the public good and a government that protected individual property rights. The discord and disorder of Fort Wilson was an anathema to the orderly society that the gentry and middling sort wished to create. As the political practices of their former allies came into contest with their philosophical ideals, the Constitutionalists chose their own ideals over the policies and people that had triggered the Fort Wilson Riot, so as to maintain virtue and restore order.[29]

It is from the belief that republics serve the public good that the dichotomy regarding the correctness of the middling sort’s actions in the early 1770s and the incorrectness of the lower sort’s later actions emerged. Eighteenth-century Whigs believed that a monarchical government could not truly support the public good because the individual desires of the monarch would always be prioritized over the needs of the community. Because the republican assembly created by the State Constitution of 1776 gave voice to the public good while the colonial government did not, elites and the middling sort felt that different rules existed for speaking out against the new government. Whigs encouraged extralegal action against and criticism of non-republican governments as a way to check the tyrannical impulses of the government and ensure that the will of the public be considered. Once government took a republican form and at least theoretically worked to serve the public good, extralegal participation became a vice and harmed the public good by introducing licentiousness and anarchy into a balanced system.[30]

By contrast, the lower sort had a completely different basis for considering republican ideals. They were unconcerned with the theoretical public good that seemed to only exist in the pages of political philosophers’ writings. Instead, they built their own republican ideology using their experiences living under and overthrowing a monarchical government. To the lower sort, the most important aim of the Revolution was to give a voice to those who lacked one under the old regime. The lower sort imbued in the Revolution a “levelling spirit,” which would erase the hierarchy of the colonial period. The protest over prices, in their minds, only involved the fact that their interests were seemingly ignored to favor the interests of the gentry. Whether the government was monarchical or republican had no bearing on their calculations. What mattered was that they felt that their needs were not being met by the current government and that they would therefore resort to extralegal means to provide for themselves. By dramatically pushing this conception of republicanism throughout 1779, the lower sort overplayed their hand. Their actions regarding price control and the violence that resulted in a deadly riot alienated Constitutionalists and radical middling men who still valued property rights and public tranquility over the democratic spirit of the masses. This ensured that the politics of the 1780s would be of a different character than the politics of the 1770s.[31]

During the 1780s, political power, both on a state and national level continued to centralize. Emblematic of this process were the passage of the Federal Constitution in 1787 and the repeal and replacement of Pennsylvania’s State Constitution in 1790. Both new constitutions incorporated aspects of the republican theory developed by the Republicans during the late 1770s while noticeably ignoring the republican theories of the crowd. These documents embraced the checks and balances and limited means of participation pushed for by the Republicans in the 1770s. They cited a need for stability and strength in government, which shows that the popular movements of the Revolution had impacted the thinking of political elites as a new American Republic was created. Perhaps most importantly, both the Federal Constitution and Pennsylvania’s new State Constitution were the products of the elite. Noticeably absent were the voices of the crowd and the lower sort. Their voices had been silent since the Fort Wilson Riot, leaving a redefinition of class boundaries in politics and elimination of the acceptance of “casual overflowings of liberty” as the riot’s ultimate legacy. The class friction evident throughout the Fort Wilson Riot and the “battle” between elites and the crowd over the boundaries of political participation have remained relevant throughout American history. Although Fort Wilson answered the question of “where does political power lie within society” for one instance of time, it was by no means a definitive answer nor a permanent one. Understanding how that one answer was reached, however, sheds light on how republican formation occurred during the Revolutionary period and provides insight into how class conflict’s interaction with ideology has impacted and will continue to impact, America’s political culture.

[1]Samuel Shaw to Winthrop Sargent, October 10, 1779, in Samuel Shaw, and N. B. W. “Captain Samuel Shaw’s Revolutionary War Letters to Captain Winthrop Sargent.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (PMHB) 70, no. 3 (1946): 281-324. Early histories of the riot viewed it as a cautionary tale regarding unrestrained democracy. They were highly critical of the crowd, generally viewing them as an unruly “mob” and not as a legitimate political actor. Additionally, most early pieces claim that the crowd always intended to strike at Wilson’s house, putting the animus of blame squarely on their shoulders. Eye witness accounts of the event directly rebut these claims and suggest that assigning blame for the riot is complex and likely impossible. More recent scholarship has been more forgiving and have placed the riot inside of the larger framework of both the stages of republican formation inside of Philadelphia and identified the crowd as a vital and legitimate part of the political culture of Philadelphia. Each of the works done by these scholars on Fort Wilson has been invaluable to me as I have written this piece. Throughout this article, I attempt to unify their work to present an accessible interpretation of Fort Wilson. I also seek to build on their pieces by further focusing Fort Wilson within the context of extralegal political participation in Colonial America and by further developing how both the upper, middle, and lower sort created republican visions and how these differences impacted the aftermath of the riot.

[2]A note on terms: Traditionally, historians used the phrase “mob” to refer to the people who marched during the incident. However, in his WMQ article on the topic, Alexander correctly argued that because of the modern usage of the word, it is a problematic one to use when attempting to be a neutral evaluator of the riot. Keeping that in mind, I will avoid usage of “mob” in favor of the less pejorative “crowd” or more encompassing “lower sort.”

[3]A. Kristen Foster. Moral Visions and Material Ambitions: Philadelphia Struggles to Define the Republic, 1776-1836. (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2004). Chapter 1 esp. 12-24; Steven Rosswurm. Arms, Country, and Class: The Philadelphia Militia and “Lower Sort” During the American Revolution, 1775-1783. (New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987). Chapters 1-3; and Richard Ryerson. The Revolution Is Now Begun: The Radical Committees of Philadelphia, 1765-1776 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978). Each of these sources addresses the nature of colonial politics in Philadelphia and protest movements that disrupted that nature in better detail than I could offer here.

[4]Pauline Maier. “Popular Uprisings and Civil Authority in Eighteenth-Century America” in WMQ, Vol. 27, No. 1 (January 1970), pp. 3-35. For more information see also:Jesse Lemisch. “Jack Tar in the Streets: Merchant Seamen in the Politics of Revolutionary America” WMQ, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Jul., 1968), pp. 371-407; Alan Taylor. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. Chapter 2-3, esp. 69-72.; Gordon Wood. “A Note on Mobs in the American Revolution”. WMQ, Vol. 23, No. 4 (October 1966), pp. 635-642.

[5]Richard Ryerson. The Revolution Is Now Begun. 25-26; A. Kristen Foster. Moral Visions. 17-18.

[7]Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776.from The Avalon Project. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/pa08.asp.; Robert F Williams. “The Influences of Pennsylvania’s 1776 Constitution on American Constitutionalism during the Founding Decade” in PMHB, Vol. 112, No. 1 (January 1988), pp. 25-48.;Gordon Wood. Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787. (Chapel Hill, 1969). 226-237.

[8]A strong initial argument against the Constitution can be found in: John Adams to Benjamin Rush, October 12, 1776 in The Letters of Benjamin Rush, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951). Vol. I. 240. Adams scoffs at the nature of the Constitution and predicts that Pennsylvanians would soon prefer the tyranny of England to the tyranny of their new charter.

[9]ThePennsylvania Gazette. “To the Citizens of Pennsylvania”. March 24, 1779.Throughout the Revolutionary Period, the two parties in Philadelphia relied on different newspapers to make their voices heard. The Republicans favored established presses such as the Pennsylvania Gazette while the Constitutionalists’ writing could be found primarily in the Pennsylvania Packet.

[10]Thomas Smith to Arthur St. Clair. August 22, 1776. in Steven Rosswurm. Arms, Country, and Class. 107

[11]Benjamin Rush to Charles Lee, October 24, 1779. in The Letters of Benjamin Rush. 244. Porter shops sold porter (dark) beer.

[12]“Principles and Articles Agreed on by the Members of the Constitutional Society”. In Pennsylvania Packet (PP). April 1, 1779. From The Library Company of Philadelphia; Staughton Lynd, Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 171.

[13]Morton M. Rosenburg. “In Search of James Wilson” in Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 55, No. 3 (July, 1988); Steven Rosswurm. Arms, Country, and Class. 176-177; “Principles and Articles Agreed on by the Members of the Constitutional Society”.

[14]Paul Langston. “A Fickle, and Confused Multitude”: War and Politics in Revolutionary Philadelphia, 1750-1783.” PhD diss., University of Colorado, 2013. Esp. Chapter 5.

[15]PP, June 29, 1779. in Ronald Schultz. “Small Producer Thought In Early America. Part I: Philadelphia Artisans And Price Control” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 54, No. 2 (April 1987), pp. 115-147

[16]Hubertis Cummings. “Robert Morris and the Episode of the Polacre “Victorious.”” In PMHB, Vol. 70, No. 3 (July 1946), 252; PP, September 10, 1779. in Ronald Schultz. “Small Producer Thought In Early America.”

[17]PP, “A Hint.” December 10, 1778. From Historical Society of Philadelphia (HSP).

[18]Elizabeth Drinker. May 22, 1779 and May 24, 1779 in The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker.ed. Crane, Elaine Forman. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1991).; “For Our Country’s good!” May 23, 1779, reprinted in Steven Rosswurm. Arms, Country, and Class.178.

[19]Benjamin Rush to James McHenry. June 2, 1779, in The Letters of Benjamin Rush. 223.; PP, June 29, 1779. in Ronald Schultz. “Small Producer Thought In Early America.”

[20]PP. September 10, 1779. in Ronald Schultz. “Small Producer Thought In Early America.”; PP. September 24, 1779. From The Library Company of Philadelphia.

[21]“Gentlemen and Fellow Citizens.” August 29, 1779. From HSP.

[22]Elizabeth Drinker. October 4, 1779 in The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker.ed. Crane, Elaine Forman. (Boston, 1991).

[23]Descriptions of the events of Fort Wilson can be found in detailed primary source accounts including: “Journal of Allen McLane,” in The Spirit of Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participantsvol. 2, Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, eds., (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1958). and Horace Edwin Hayden, ed., “The Reminiscences of David Hayfield Conyngham, I750-1834.” in Wyoming Historical and Geological Society, Proceedings and Collections, VIII, 208-215. Additional details can be found in secondary sources including: John K. Alexander. “The Fort Wilson Incident of 1779: A Case Study of the Revolutionary Crowd.” William and Mary Quarterly. Volume 31 Number 4 (October 1974) 589-612.; C. Page Smith. “The Attack on Fort Wilson” in PMHB, Vol. 78, No. 2 (April 1954), pp. 177-188; A. Kristen Foster. Moral Visions and Material Ambitions. 121-124; and Steven Rosswurm.Arms, Country, and Class. Chapter 7, esp. 210-217.

[24]Samuel Rowland Fisher and A. (W.) Morris. Journal of Samuel Rowland Fisher of Philadelphia, 1779-1781. Philadelphia, 1928. 27-29.

[25]Samuel Patterson in Caesar Rodney and George Herbert Ryden. Letters to and From Caesar Rodney, 1756-1784. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1933). 323.

[26]Elizabeth Drinker. October 7, 1779.; Benjamin Rush to John Adams. October 12, 1779. The Letters of Benjamin Rush.

[27]PP. October 9, 1779 and October 12, 1779. From The Library Company of Philadelphia. The final idea of this paragraph borrows from Steven Rosswurm. Arms, Country, and Class. 226-227.

[28]Joseph Reed and William B. Reed. Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847). 139,163.; PP. October 16, 1779. From HSP.; A. Kristen Foster. Moral Visions and Material Ambitions.124-125

[29]See Gordon Wood. Creation of the American Republic. Chapter 11, esp. 55-70.

[30]Gordon Wood. Creation of the American Republic. Chapter 11. esp. 62-65.; A. Kristen Foster. Moral Visions and Material Ambitions. Chapter 4.

[31]A. Kristen Foster. Moral Visions and Material Ambitions. 125-128.; Steven Rosswurm. Arms, Country, and Class. Chapter 8.

6 Comments

One of the most fascinating aspects of the American Revolution is the tightrope that the leaders/elites walked releasing popular passions to their ends while also restraining them — especially in contrast to comparable contemporary revolutions. Interesting analysis of an example of this.

Interesting article. Glad to see articles from college students on JAR which hopefully indicates that his generation is interested in history.

A note of interest, I believe Benedict Arnold was at the Wilson house theday ofthe attack. Arnold was the military governor of Philadelphia during that period. Although he was there in support of Wilson, the Joseph Reed faction was very disatisfied with him in that capacity. They ultimately brought charges against him.

Very well done. I agree with Geoff that the undercurrents of domestic political social, political, economic, and security disagreements that American political leaders had to navigate during this period were some of the most demanding challenges any generation has faced. In a lot of ways, they make today’s political debates seem pitiful. It only increases my awe for the founding generation.

Totally agree, Eric, especially when you consider how new and relatively wobbly the new government was at that time. I’m right there with your sense of awe; this just increases the respect I’ve held for many years.

I appreciate this article’s effective narration and attempt to present the various perspectives on the conflict. Well done. It is fascinating how much this struggle between republican notions of government and democratic notions of government are literally manifest in our two party system.

I was trying to find a reference from a book I’m reading called “A People’s History of the United States,” by Howard Zinn, where he mentions this story about the Fort Wilson riot. However, I couldn’t find it, the quote made by the author was that the “silk stocking brigade,” well off Philadelphians, turned away the militia.

Anyway, I’m not disputing anything except to say I thoroughly enjoyed reading the article. I have to be honest, it reads as if it’s from today. Eerily familiar.