November 10, 1775 was an important day in both Great Britain and America. Lord George Germain assumed duties as the Secretary of State for the American Department—“he was virtually War minister in the British cabinet”—and the Continental Congress authorized two battalions of marines, giving birth to the United States Marine Corps.[1] Two hundred and forty-three years later, on November 10, 2018, on a sunny Saturday morning, in conjunction with Veteran’s Day, a group of about seventy-five citizens gathered in the City of Virginia Beach, Virginia, to dedicate a historic highway marker to commemorate the 1775 skirmish at Kemp’s Landing. The Virginia Beach Department of Public Works placed the marker near the intersection of Witchduck Road and Singleton Way, located adjacent to the now heavily traveled intersection of Kempsville, Witchduck, and Princess Anne Roads in Virginia Beach. The citizens attending this dedication included two city council members, a member of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR), and an eclectic coalition of local organizations and individuals working together to preserve and promote the history of Kempsville, Virginia Beach, and the region.[2]

Approval and Dedicating the Historic Marker

The City Council of Virginia Beach created the Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission (VBHPC) in 2008, a board of appointees that advises the council on issues related to historic preservation.[3] The VBHPC awards grants to promote research on topics of local historic interest in the City of Virginia Beach. The City of Virginia Beach, the largest city in Virginia, includes all of the former Princess Anne County. (Princess Anne County dates from 1691 but is now extinct as a political entity, subsumed by Virginia Beach in 1963.)[4] Kemp’s Landing was one of the original populated areas in the largely rural and agrarian Princess Anne County. The VBHPC approved the findings of researcher Christopher Pieczynski, who received a grant during 2017 to explore the details of the skirmish at Kemp’s Landing and evaluate the historical significance of the event.

Virginia hosts the oldest highway marker program in the United States, a program initiated in 1927 as automobile travel and highway construction facilitated travel by the masses. Today, the Virginia Department of Transportation and the DHR manage the Historic Highway Marker program in the state. The Virginia DHR approved the request for the installation of an historical marker resulting from Pieczynski’s research related to the skirmish subsequently endorsed by the VBHPC. This new marker is one of more than 2,700 statewide that commemorate people, places, or events of regional, statewide, or national significance, many associated with the Revolutionary period.[5]

The 1775 Environment

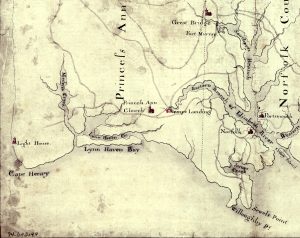

The skirmish between Lord Dunmore’s British troops and the Princess Anne County Militia actually took place on Wednesday, November 15, 1775, five days after the important events of November 10.[6] During the late 1700s, Kemp’s Landing was an important commercial transshipment point at the headwaters of the eastern branch of the Elizabeth River. Here, cargo shipped by wagon from Princess Anne County and points south, principally South Norfolk County and the Albemarle region of North Carolina, proceeded by water west to Norfolk, Virginia, where merchants then shipped the raw materials on deeper draft ocean going vessels to other points in the British Empire. Several warehouses and a small community occupied the site. Kemp’s Landing was one of several critical geographic points in the local transportation system. The second critical point was a narrow causeway and bridge twelve miles south of Kemp’s Landing along Kempsville Road known as Great Bridge. The low and swampy terrain surrounding Norfolk, bisected by many tidal streams and tributaries, resulted in these critical transportation choke points. Both of these sites constituted key terrain features the Whigs, referred to as rebels by the British, and the Loyalist British Government or Tories, headed by the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, needed to control. Control of Great Bridge and Kemps Landing greatly facilitated control of Norfolk.

Norfolk: the Key to Holding Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay

The leaders of the rebel governments of both North Carolina and Virginia understood the critical importance of the city of Norfolk and the transportation choke points of Kemp’s Landing and Great Bridge providing the only land access on the east side of the Great Dismal Swamp to points east and south of the city. Norfolk was the eighth largest city in North America in 1775 and a center of commerce serving the Chesapeake Bay region; Norfolk had a population of approximately 6,250, twice the size of Savannah, Georgia. It was the largest city between New York and Charleston and was a thriving port city providing access to the hinterland and Chesapeake Bay. Norfolk represented a secure port suitable for basing British warships capable of interdicting rebel commerce in the Chesapeake Bay. Forty percent of the goods shipped from the thirteen colonies in 1775 transited the Chesapeake Bay. Holding Norfolk guaranteed control of this commerce, so critical to maintaining the mercantile system that powered the British economy.[7] Whoever controlled Norfolk—Whig or Tory—had a significant military and economic advantage in the contest to control the thirteen rebellious colonies.

Unable to maintain control of the city of Williamsburg, the capitol of Virginia Colony, Lord Dunmore established his royal government aboard ship and sailed for Loyalist-dominated Norfolk to rally support for the King. In Norfolk, Dunmore found a loyalist merchant class sympathetic to his goal of maintaining control of the colony for the Crown. He called for reinforcements of both land and naval forces because he understood the forces at his disposal lacked the strength to counter the aggressive military moves of the rebel Virginia government.[8]

Lord Dunmore’s Military Actions to Disrupt the Rebellion

Responding to Dunmore’s call for British regular troops and British navy warships, elements of the 14th Regiment of Foot, then stationed at Saint Augustine, East Florida, moved to support Dunmore in Virginia. Under Dunmore’s direct personal supervision and professionally led by Capt. Samuel Leslie of the 14th Regiment, Dunmore initiated a series of successful raids, using land and naval forces, to maneuver throughout the waterways and countryside to seize weapons and war material, gain intelligence, and disperse rebel militia. During October, Leslie’s troops seized over seventy pieces of ordnance, some as large as twelve pounds, and detained and interrogated local Patriot political and militia leaders, gaining valuable intelligence on the size, scope, and seriousness of the rebel movement. Kemp’s Landing was the sight of one of these October raids.

On October 17, 1775, a British force of over one hundred soldiers, sailors, and marines embarked at Norfolk at about two o’clock in the afternoon and proceeded up the eastern branch of the Elizabeth River. The force covered their movement and disembarkation with naval guns, landing east of Norfolk at Newtown. The landing force then marched three miles overland to Kemp’s Landing where they arrived after dark. The British raiders encountered no opposition even though intelligence reports indicated over 200 militia were in the vicinity. They searched several warehouses, locating “a good many small arms, musket locks, a little powder and ball, two drums, and a quantity of buckshot, all of which we either brought off or destroyed.” The raid also netted two prisoners, militia Captain Matthews and a delegate to the Virginia convention, representing Princess Anne County, William Robinson. The force narrowly missed interdicting a large shipment of powder. On October 20, Dunmore received an additional sixty reinforcements from the 14th Regiment under command of Capt. Charles Fordyce.[9]

On November 14, 1775, in order to mask their movement from the rebels under the cover of darkness, Lord Dunmore and a detachment under command of Captain Leslie moved by boat down the south branch of the Elizabeth River. The British arrived about daylight the next morning, advancing several miles south of Great Bridge in an attempt to locate and engage the rebel militia assembling to defend that key location. Failing to locate the rebels, the British revised their plan. Lord Dunmore then ordered a march to Kemp’s Landing where intelligence indicated 300 to 400 militia assembled in response to the British movements. Before departing Great Bridge, Dunmore left a detachment and ordered the construction of a wooden fort to establish a permanent presence to secure the strategically import location.

Dunmore and Leslie then advanced overland about twelve miles north to Kemp’s Landing. As the British came within sight of the settlement their advance guard received fire from the militia concealed in a thick wood on their left flank. The militia fired on the British advance guard, failing to allow the main body to enter the ambush zone, a serious but common mistake by inexperienced and nervous soldiers. The rebels likely selected the position because of the cover and concealment provided by the thick woods. It proved a poor choice because the low swampy terrain behind the woods provided poor egress for the ambushers when aggressively pursued by the British. Reacting to the ambush, the disciplined British soldiers turned towards the fire and dispersed the attackers. During the ambush and the pursuit, one British grenadier received a wound in the knee, the only British casualty. The rebels were not as fortunate. British musket fire killed five rebels, two others drowned in the swamps and tributaries of the Elizbeth River as they attempted to escape, and the British reported an unspecified number of wounded rebels.[10]

Initially, the British took Colonel Hutchings and seven men prisoner. In the days following the skirmish, the British rounded up Colonel Lawson and seven more men. Lord Dunmore remained in the vicinity for the next several days. The success Dunmore’s troops achieved at Kemp’s Landing and the weak and ineffective resistance displayed by the Princess Anne County Militia emboldened Lord Dunmore. On November 16, from the Kemp’s Landing home of a Loyalist, John Logan,[11] Dunmore issued his proclamation, dated November 7, 1775, declaring martial law, to free “all indented Servants Negroes or others (appertaining to Rebels,) . . . that are able and willing to bear Arms,” and requiring all subjects to join the British cause.[12] Captain Leslie’s informed analysis, however, was less optimistic about garnering support from the local population, recognizing that the quantity of arms discovered was “proof that it would require a very large force to subdue this Colony.”[13] After the success at Kemp’s Landing and with the late October reinforcements from the 14th Regiment, Dunmore opted to deploy his forces to seize control of Great Bridge before North Carolina forces arrived to augment the Virginians.[14]

Dunmore understood that this may have been the only opportunity to maintain control of the Virginia Tidewater region and protect the citizens and city of Norfolk from rebel occupation. Dunmore’s naval forces actively contested the movement of Col. William Woodford, commanding the 2nd Virginia Regiment and the Culpeper County minutemen as they attempted to cross the James River from the Virginia Peninsula in route to Norfolk. Woodford’s route to threaten Norfolk was somewhat circuitous because rebels lacked maritime support and the British patrolled the James and Elizabeth Rivers that provided the only direct access to that port city. Woodford crossed the James River west of Jamestown Island, forty miles west of Norfolk, landing in modern day Surry County near Grays Creek, requiring an overland march of sixty miles to reach Great Bridge. From Great Bridge, Woodford would advance to Kemp’s Landing, then on to Norfolk.[15]

Ultimately, Dunmore’s failed assault on Great Bridge on December 9, 1775, resulted in the British evacuation of the Tidewater region, the rebel occupation and then destruction of Norfolk, solidifying rebel control of the landward portions of the Chesapeake Bay for nearly the entire American Revolution.[16] Although Kemp’s Landing was a minor skirmish, it was one identifiable action in a sequence of events that helped to shape the outcome of the American Revolution, facilitating Whig political control of Virginia. It is very appropriate that the grass roots effort to recognize the event by placing a Virginia Highway Roadside Marker near the site to commemorate the skirmish took place two hundred and forty-three years later, in conjunction with Veteran’s Day. Lest we forget the importance of the individuals present and ideas represented by their actions that day in November 1775.

[1]Worthington C. Ford, et al., ed., Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington, DC, 1904-37), November 10, 1775, 3: 348, /memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00344)), accessed October 28, 2018; and Gerald S. Brown, The American Secretary, the Colonial Policy of Lord George Germain, 1775-1778 (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1963)1.

[2]Participants and attendees of this dedication ceremony included: Christopher Pieczynski, primary researcher; Nosuk Pac Kim, Virginia Board of Historic Resources; Jessica Abbott, Kempsville District, Virginia Beach City Council; Jimmy Wood, VBHPC and Virginia Beach City Council; Bobbie Gribble, Historic Kempsville Citizens Action Committee; Sons of the American Revolution; Daughters of the American Revolution; African American Cultural Center, Princess Anne County Training School, Kempsville Union High School Alumni and Friends Association, Inc., and others.

[3]Virginia Beach News Center, City of Virginia Beach, “November 2, 2018, Skirmish at Kemp’s Landing Virginia Historical Marker to be Dedicated Nov. 10,” www.vbgov.com/news/pages/selected.aspx?release=4063&title=skirmish+at+kemp%E2%80%99s+landing+virginia+historical+highway+marker+to+be+dedicated+nov.+10, accessed November 10, 2018.

[4]Emily J. Salmon and Edward D. C. Campbell, Jr., eds., Hornbook of Virginia History (Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, 1994), 186; Princess Anne County became extinct when the former county merged into the City of Virginia Beach in 1963.

[5]Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Historic Highway Markers, www.dhr.virginia.gov/highway-markers/,accessed October 28, 2018; and City of Virginia Beach, Minutes of Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission, October 4, 2017, www.vbgov.com/government/departments/planning/boards-commissions-committees/Documents/VA%20Historical%20Preservation/2017%20Agendas%20and%20Minutes/10042017%20HPC%20GenMeeting%20Minutes%20Approved.pdf, accessed October 28, 2018.

[6]Samuel Leslie to William Howe, November 1 (postscript November 26), 1775, in Peter Force ed., American Archives, Documents of the American Revolutionary Period, 1774-1776 (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1844), ser. 4, 3: 1717.

[7]Paul H. Smith, Loyalists and Redcoats: A Study in British Revolutionary Policy (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1964), 82-109; John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783 (Charlottesville, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 26, 204-210; Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America 1743-1776 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955), 217; and Ernest McNeill Eller, ed., Chesapeake Bay in the American Revolution (Centerville, MD: Tidewater Publishers, 1981), 312.

[8]Lord Dunmore to Samuel Graves, May 1, 1775, in William B. Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Naval History Division, Department of the Navy, 1964), 1: 257-8, www.ibiblio.org/anrs/docs/E/E3/ndar_v01.pdf, accessed November 5, 2018.

[9]Leslie to Howe, November 1, 1775 (postscript November 26); Examination of William Robinson, October 22, 1775, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 3: 1717; Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 62; and Alexander Ross to Captain Stanton, October 4, 1775, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 4: 335-6, amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A91713, accessed November 5, 2018. By late October 1775, the Virginia detachment of the 14th Regiment was made up of about 150 members of the unit. The regiment had lost many men to disease while serving in the Caribbean and was severely understrength in 1775. It would later return to Britain to reconstitute. “Observations on the Conduct of Lord Dunmore,” October 27, 1775, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 3: 1191-2.

[10]Leslie to Howe, November 1, 1775 (postscript November 26).

[11]Christopher Pieczynski, Remarks at the Skirmish at Kemps Landing, State Historic Highway Marker Dedication, November 10, 2018.

[12]“Williamsburg,” Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter), November 25, 1775, research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?issueIDNo=75.DH.54&page=3&res=LO, accessed November 6, 1775; and Lord Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, December 6, 1775, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 2: 1309-11, www.ibiblio.org/anrs/docs/E/E3/ndar_v02.pdf, accessed November 13, 2018.

[13]Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 63.

[14]During this critical period the Virginia and North Carolina governments worked together to prevent the royal governor, Lord Dunmore, from establishing British control of the Tidewater region; see Minutes of the Virginia Convention December 1, 1775, in William Laurence Saunders, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina (Raleigh NC: P.M. Hale, 1886), 10: 396, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr10-0152; Charles E. Bennett and Donald R Lennon, A Quest for Glory: Major General Robert Howe and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 28.

[15]“Williamsburg,” Virginia Gazette(Purdie), November 17, 1775, research.history.org/CWDLImages/VA_GAZET/Images/P/1775/0263hi.jpg, accessed November 6, 2018; and John Page to the Virginia Delegates of the Continental Congress, November 17, 1775, in Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 2: 1061; John Page to Thomas Jefferson, November 11, 1775, ibid., 2: 991-3; and Virginia Committee of Safety to the Delegates in the Continental Congress, November 11, 1775, ibid., 2: 993-5, www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/publications/naval-documents-of-the-american-revolution/NDARVolume2.pdf, accessed November 6, 2018. Colonel Woodford received orders dated October 24, 1775 to advance on Norfolk; elements began crossing the James River on November 7. Woodford was in Suffolk on November 29, finally closing on Great Bridge on December 2; see Brent Tarter, “The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment, College Camp, Oct. 26 1775 & 6 Nov.,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 85, 2, (April 1977) n54, 70 and 71, 173 & 180; and D. R. Anderson, ed., Richmond College Historical Papers, The Letters of Col. William Woodford, Col. Robert Howe and Gen. Charles Lee to Edmund Pendleton (Richmond, VA: Richmond College, 1915), Camp Suffolk, November 29, 1775, 104, archive.org/details/richmondcollege00richgoog/page/n108,accessed November 12, 2018.

[16]J. T McAllister, Virginia Militia in the Revolutionary War (Hot Springs, VA: McAllister Publishing Co., 1913), 1, lib.jrshelby.com/mcallister-harris.pdf, accessed October 28, 2018. For more details on the destruction of Norfolk see, Patrick H. Hannum, “Norfolk, Virginia, Sacked by North Carolina and Virginia Troops,” Journal of the American Revolution (November 6, 2017), allthingsliberty.com/2017/11/norfolk-virginia-sacked-north-carolina-virginia-troops/, accessed November 6, 2018.

Recent Articles

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

Recent Comments

"The 100 Best American..."

I would suggest you put two books on this list 1. Killing...

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Eugene Ginchereau MD. FACP asked for hard evidence that James Craik attended...

"The Monmouth County Gaol..."

Insurrectionist is defined as a person who participates in an armed uprising,...