Early one morning in late June 1778, an unknown passerby tossed a package of documents that clanged against the gate at Benjamin Franklin’s home in Passy, France.[1] In it was a letter addressed to Franklin dated June 16, 1778 from one “Charles de Weissenstein,” writing from Brussels. In addition to the letter, the package contained two other documents, titled Project for Allaying the Present Ferments in North America and An Outline of the Future Government in America. The flurry of activity that followed provides a unique window into the state of both American and British thinking on the Revolution at the time and the nature of the alliance between France and America. It also provided bit of drama: a clandestine rendezvous that turned into a police chase. Was this now nearly forgotten incident a sideshow, almost comical if the issue at hand was not so serious, or was it a serious attempt to facilitate reconciliation between Great Britain and America? It’s worth revisiting what happened.

The creation of plans designed to keep America in the British empire or otherwise end the war was practically a cottage industry during this period, so by itself the appearance of yet one more plan was not unusual, even if the method of delivery was a bit out of the ordinary. Many of these proposals were offered anonymously, so the fact that “Charles de Weissenstein” was quickly recognized as a fictional name was also unexceptional. However, upon further examination something about the contents of this package seemed different and worth more serious consideration.

In mid-1778 Great Britain’s was licking her wounds from the crushing loss at Saratoga in late 1777. Besides thwarting of the British plan to divide the colonies along the Hudson corridor, this defeat gave the Americans legitimacy on the world stage, opening possibilities for alliances and badly-needed loans, both of which soon materialized with France. On the home front, their flagging war fortunes increased division politically and in popular opinion. Even among war supporters, criticism of military tactics and strategy became more strident.

The French alliance, signed in Paris on February 6, 1778 and ratified by Congress on May 2, had fundamentally changed the complexion of the conflict. With France in the fray, and Spain and The Netherlands likely to follow, Britain found itself in a world war. The need to defend other interests around the globe, such as Gibraltar and the West Indies, necessarily diminished the importance of the situation in the rebellious American colonies.[2] They had dispatched the Carlisle Commission to America in yet another attempt for a negotiated settlement. At home the ministry continued to waffle about recognizing (and therefore legitimizing) the American Congress and, most critically, about whether to recognize American independence. The Commission arrived in in America in June 1778, scarcely a month after Congress ratified the French alliance. In the opinion of some, “if the Peace Commission under the Earl of Carlisle had reached America before news of the French alliance, its terms might well have been accepted.”[3] Such is the importance of timing in history.

The Americans, despite the exhilaration of the victory at Saratoga, had their own issues. Their depleted military was limping out of the miserable winter in Valley Forge, not fully breaking camp until June. Since the British seizure of Philadelphia in late 1777, Congress was operating out of York, Pennsylvania. The performance of Washington’s forces in the Pennsylvania battles of late 1777 defending Philadelphia had been dismal. A defeat of Howe around Philadelphia, coupled with the Saratoga outcome, might have brought more palatable peace overtures from the British. In summary, American fortunes were on the upswing, but there was a long slog still ahead.

The Carlisle Commission was aware of the French alliance but immediately shocked by the news that a British evacuation of Philadelphia was imminent.[4] They offered a package to the Congress, still holed up in York. The terms provided for American self-government and representation in Parliament, but not recognition of America’s independence.[5] Because of the latter omission, hardliners kept Congress unmoved. Meanwhile, across the ocean in France, the de Weissenstein drama unfurled.

The Letter

The package that hit the gate at Passy that day in June included a six-page handwritten letter, in English, from “de Weissenstein.” According to John Adams, Franklin identified in the letter earmarks of it having come from the King himself, though neither Adams nor Franklin ever recorded what traits the latter suggested such a thing. This attribution to the King could be genuine or, as historian Neil L. York suggests, the irreverent Franklin may have been having a little fun with the ever-earnest Adams. York writes: “Franklin’s comments probably had more to do with the strained relations between the two diplomats than any belief on Franklin’s part that the King had been privy to the plan. Adams, insecure and jealous of Franklin’s status, may have just gotten on the Pennsylvanian’s nerves.”[6]

The cover page of the letter started with the admonition to “Read this in private and before you look at the other papers – but don’t be imprudent enough to let anyone see it before you have considered it privately.”[7] Starting on a positive note, de Weissenstein identifying himself as an Englishman who, while fond of order, was “no[t] yet one who is an idolatrous worshipper of passive obedience to the divine Right of Kings.” He flattered Franklin as “a Philosopher, whom nature, industry, and a long experience have united to form, and to mature. It is to you therefore I apply.” He went on to acknowledge the errors of the British regime, whose acts amounted to a “Stupid narrow-minded Despotism.”[8]

The tone then darkened as the writer turned his sights on the French alliance, arguing that the French were untrustworthy and would eventually turn on America:

The Progress of this new alliance is easily foreseen … For the present, and for a year or two to come, ye will obtain the most ample promises, and ready acquiescence. Then will come evasions to your applications, contemptuous delays, and of a sudden, a declaration that ye must shift for Yourselves… In that there may probably be a great Mistake, but with respect to America there can be no such Error, for when will she be able to combat France, and compell her to adhere to Treaties.[9]

Hitting closer to home, de Weissenstein dismissed both America’s ability to win the war and then to defend itself as an independent nation. This struck at the heart of what the patriots had considered the starting point in any credible negotiation – recognition of America’s independence:

It is one thing to elude the Combat, another to vanquish Your adversary. The Maintenance of a Standing Army, and the Creation of a Regular Navy are not within the Compass of an inconsiderable revenue, and thinly peopled Country nor can attend the efforts of a few years, be activity and success as favorable as imagination can paint. Yet without these, your rising state will neither be in a capacity to secure itself from Hostile ravages, acquire new alliances, or preserve to any beneficial purpose, that which is already formed … Our Title to the Empire is indisputable, and will be asserted either by ourselves, or successors whenever occasion presents. We may stop a while in our pursuit to recover breath, but shall assuredly resume our career again.[10][emphasis mine]

The denial of independence ended any serious consideration Franklin may have had of the proposal, if he even lasted that far. We shall later see his vitriolic response.

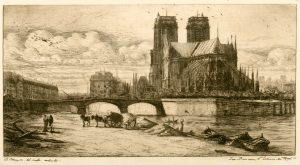

Where the plot thickened was in the conditions for response outlined in the letter. Franklin was asked to bring his reply to the Cathedral of Notre Dame between 12:00 and 1:00 p.m. on July 6 or July 9 and drop it off where a courier for de Weissenstein would be by the altar, “having a Paper in his hand as if drawing or taking notes.”[11] Franklin was to drop the response there and then leave immediately. If unable to access this part of the cathedral (which was gated off in places), Franklin was to locate a person in one of the aisles “who will have a Rose, either in his Hat, which he will hold in his hand up to his face, or else in the buttonhole of his waistcoat.”[12]

The courier would have no awareness of what he was carrying, and de Weissenstein wished to keep his identity masked:

It matters very little for you in this state of busyness to indulge your curiosity in knowing who I am. I can serve you more effectually while invisible. If I succeed, perhaps I may never reveal myself; If I fail, surely my intentions merit some consideration from Men professing Patriotism.”[13]

Franklin and Adams immediately broke the privacy request and brought the letter to their new ally, in the person of the French Foreign Minister, the Comte de Vergennes. Together they hatched a plan to bring in Paris police to stake out the pickup spot and attempt to apprehend the person picking up the documents, with hopes of using him to find out the identity of de Weissenstein. The police report, in French, still exists and with help of a neighbor who translated the document for me, I can report what happened next.[14] But first let’s discuss the rest of de Weissenstein’s proposal.

The Proposals

The attachments to the letter detailed two aspects of a reconciliation plan: how the transition would take place and how the new government would be structured. Project for allaying the present ferments in North America dealt with the first topic. Totaling eighteen articles, it detailed logistics such as the secrecy around the agreement (the first six articles were never to be released, the rest could be published once the agreement was consummated), safe passage to England for American negotiators while a state of war still existed, and how the suspension of arms would take place. By far the most interesting articles were numbers four and eight. Article four discussed how American leaders of the rebellion would be indemnified and kept safe from reprisals. In a component that was anathema to American notions of equality, it proposed the creation of an American hereditary peerage, going as far as to list four names of people who would become peers and receive permanent pensions. They were Adams, John Hancock, George Washington, and Franklin. The agreement also made provisions for the designation of others to be added to that list.[15] Article eight, brief but important, discussed how America’s newly minted ally would be cast off, stating simply:

The crown shall take upon itself to adjust the treaty between America and France which shall be laid before his Majesty in entire for his full information with respect thereto. A mode of notifying it to the court of France shall be settled.[16]

Great outline of the future governments in North America laid out in thirteen articles “A great and solemn compact … to be registered in the archives of every state of America” that would be “perpetual and irrevocable but by the free and mutual consent of both countries.” The agreement would leave the governments of the existing colonies (states) in place but stipulated that the legislatures swear allegiance to the King. Further, it cancelled all existing laws promulgated by Parliament with respect to America, thus removing the major causes of the rebellion. It proposed to establish a Supreme Continental Court which would have jurisdiction over all the colonies and whose decisions could be appealed only to the House of Lords. It provided for an upper house Congress, a body that would be called into session every seven years or sooner, all at the King’s discretion. All military operations would be placed under the Crown, with America to pay its share of the cost on a population-based pro rata allocation to the individual states, with stiff penalties for non-payment. The balance dealt with trade and tariff issues.[17]Interestingly, unlike many of the other proposals for a new continental government, there was no provision for any American-based executive function, no American president.

The (Unsent) Reply

The failure to recognize America’s independence probably doomed de Weissenstein’s proposal from the start. Further, Franklin was no friend of the British ministry (or they of him), still smarting four years after his famous dressing down by Alexander Wedderburn in front of the Privy Council. Hence Franklin’s reply, which addressed only three of the articles in the attachments, dripped with venom and anger that overshadowed his point-by-point refutation of de Weissenstein’s proposals. As the plan was to share the draft reply first with Vergennes, Franklin may have been laying it on even thicker to demonstrate to his French partner America’s devotion to their newly formed alliance.

The opening salvos laid into the British ministry:

As to my future Fame, I am content to rest it on my past and present Conduct, without seeking an Addition to it in the crooked dark Paths you propose to me, where I should most certainly lose it. This your solemn Address would therefore have been more properly made to your Sovereign and his venal Parliament. He and they who wickedly began and madly continue a War for the Desolation of America, are alone accountable for the Consequences.

But I thank you for letting me know a little of your Mind, that even if the Parliament should acknowledge our Independency, the Act would not be binding to Posterity, and that your Nation would resume, and prosecute the Claim as soon as they found it convenient. We suspected before, that from the Influence of your Passions, and your present Malice against us, you would not be actually bound by your conciliatory Acts longer than till they had serv’d their purpose of inducing us to disband our Forces[18]

The de Weissenstein proposal for the establishment of an American peerage was another major target of Franklin’s wrath; he may have seen it as one indication of the King’s involvement:

… you offer us Hope, the Hope of Places, Pensions and Peerages. These (judging from yourselves) you think are Motives irresistable. This Offer, Sir, to corrupt us is with me your Credential; it convinces me that you are not a private Volunteer in this Negociation. It bears the Stamp of British-Court-Character. It is even the Signature of your King …We must then pay the Salaries in order to bribe ourselves with these Places. But you will give us Pensions! probably to be paid too out of your expected American Revenue … Peerages! — Alas, Sir, our long Observation of the vast and servile Majority of your Peers, voting constantly for every Measure propos’d by a Minister, however weak or wicked, leave us small Respect for that Title.[19]

This letter was first given to Vergennes. He apparently elected to let the matter lie; the letter was never delivered at the Notre Dame rendezvous. As far as can be determined, no formal notification about this proposal was relayed to Congress or anyone else in America. Adams did refer to it in passing in a letter to Congressman Elbridge Gerry, talking in general about British peace overtures and adding, “we had an Example, here last Week … A long Letter, containing a Project for an Agreement with America, was thrown into one of our Grates … There are Reasons to believe, that it came with the Privity of the King.” Like Franklin, Adams zeroed in on the peerage issue, stating that while the letter was “Full of Flattery,” it was also full of bribery,

proposing that a Number not exceeding two hundred American Peers should be made, and that such as had stood foremost, and suffered most, and made most Enemies in this Contest, as Adams, Handcock, Washington and Franklin by Name, should be of the Number … Ask our Friend [who Adams is referring to is not clear], if he should like to be a Peer?[20]

He also referred to Franklin’s caustic response, saying, “Dr. Franklin .. sent an Answer, in which they have received a Dose that will make them sick.”[21] In this he was wrong, as Franklin’s response never got past Vergennes, but he was right about how the British would have reacted. Later, as part of a characteristically long, rambling screed about the letter in his diaries (“An aristocracy of American peers!”), Adams called the letter “very weak and absurd and betrayed a gross Ignorance of the Genius of American People”.[22]

The Stakeout

The Paris police did indeed stake out the drop-off point, the Cathedral of Notre Dame, as requested by Vergennes. There was no intent to hand over any reply. A copy of the police report documenting the incident, dated July 7, 1778 was relayed to Franklin soon thereafter. The officer in charge “went to the church of Notre Dame yesterday at 11am with three bodyguards whom I posted inside and outside to observe the stranger of interest and those who would come and accost him.”[23] The stranger showed up at “12:00 sharp” and found his movement restricted by the “iron gates” referred to in the de Weissenstein letter.[24] These gates locked off various shrines within the cathedral which contained exhibits of value (statues, vases, etc.). According to the report “a man sweeping the floor came up to offer to let the stranger inside” some of these areas, and the stranger “had the sweeper open seven or eight of these.”[25] As advertised, the stranger then wandered around the area “examining the chapels [exhibits] and scribbled or wrote in short bursts” on some paper he carried. At 1:15, “seeing no one, the stranger left.” The police proceeded to tail him past several streets (covering roughly one to one and a half miles), the subject “looking as though he were dreaming [preoccupied or deep in thought].” The pursuit ended at the Luxembourg Hotel.[26]

At the hotel, they at last confronted the man, and “learned that he was Monsieur Jennings, Captain of the Guards of the King of England about four or five years ago.” They further learned “his father had been a minister in the court of some other land.” They described Jennings as “between the ages of 36 and 40, about 5’2” in height, with extremely blond hair … a very thin face and a swarthy or tanned complexion.” In his stay at the hotel (he arrived June 20) he had reportedly seen no one.[27] The suspect was not arrested, there being nothing to charge him with, and the police followed up no further. He left the country shortly thereafter.

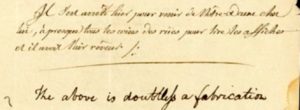

One added twist to add to the mystery: At the bottom of the police report is written, in a comment apparently added later in different handwriting and in English “The above is doubtless a fabrication.”[28]

Who Was Charles de Weissenstein?

Franklin, Adams and Vergennes all thought that the man the police tailed was “Charles de Weissenstein” himself. The German name “Weissenstein” means literally “white stone” in English. Applied to a person, it means a person with white hair, beard, or skin.[29] This meshes with the “blond hair” cited in the police report, though not so much with the “swarthy or tanned complexion.” Also, “Charles” may have come from the name of Jennings’ son.[30]

Building on what the police discovered, speculation was that the deliverer, but not the writer, was Sir Philip Jennings (1722–1788), a former major in the horse guards (1741-1770) and a current member of Parliament.[31] He was also known as Philip Jennings-Clerke and served in Parliament under that name from 1768 to 1788. Parliament was not in session during his time in France. He was granted a baronetcy by the King in 1774,, 1stBaronet of Duddlestone Hall, that after his death passed briefly to son Charles, who died four months later, ending the line.[32] He was remembered by one colleague as “a man of unquestionable integrity, but not endowed with superior parts,”[33]and by another commentator as “one of the most persevering men in any business he chose to undertake.”[34] His support in Parliament for conciliatory measures toward America (including recognition of the Continental Congress) lends credence to his involvement in this affair.[35]I could find no records of what Jennings-Clerke looked like or how tall he was, so was unable to corroborate the description in the police report. He would have been fifty-five or fifty-six years old at the time, significantly older than the police estimate of thirty-six to forty. His father was also an MP and though he had no service in a foreign land his father-in-law, Charles Thompson, was a member of His Majesty’s Council in Jamaica until 1711.[36]

Jennings-Clerke opposed the war, stating in Parliament in late 1777:

Having constantly opposed the American war from the commencement of it as thinking it might and ought to have been avoided, and for other reasons which I have frequently offered in this House … it will not be wondered at that I should now refuse to give my assent to those parts of the Address which are to convey assurances to the Throne of our intentions to furnish means of prolonging and continuing the war.[37]

Closing Thoughts

The first question must be: Did this event occur? Despite the notation on the police report, the correspondence of Franklin and Adams and the diaries of the latter indicate that it did. Yet they never reported it to Congress, meaning that if it was real, Adams and Franklin didn’t take it very seriously. The letter writer’s arrogant comments regarding both the recognition of American independence and the alliance with France rendered it unworthy of serious consideration and rendered moot both the questions of who wrote the proposal and whether any serious action should be taken. Jennings-Clerke, assuming he was “de Weissenstein,” was a ten-year MP and member of the King’s guard and thus a person of some standing. Was he acting on his own or in an official capacity and, if the latter, at whose behest? Franklin professed to have thought the letter had the King’s fingerprints on it; perhaps the Carlisle Commission was the public channel to the Franklin back-channel? Being in France, Franklin would offer much quicker return communication, but given his poor relationship with the crown, would the King even try to negotiate with him? The instructions to the Carlisle Commission authorized them to make concessions like some of those in the de Weissenstein proposals, though, significantly, two of the major items, establishment of an American peerage and disposing of the French treaty, were not mentioned[38](the latter perhaps it was agreed to just before the Commission’s departure to America).

In my opinion, the King would not attempt to treat with Franklin at this point (although a subsequent ministry under him would do so under different circumstances in 1783),[39] so Jennings-Clerke was either acting on his own or on the orders of a lower level authority. Does all this make the whole affair irrelevant? In some ways perhaps, but it is one of the more colorful demonstrations of the British regime’s continued resistance when it came to American independence, even in light of military defeats and the Franco-American alliance. Additionally, the proposal of an American peerage demonstrates a serious misunderstanding of the American mind. This blindness as it pertained to American motives, and the hard line taken by the British throughout the revolution, provides good insight into the causes of the British loss of the American colonies.

[1]Massachusetts History Online. Adams Papers, Diary of John Adams, 4: 150, www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/DJA04d106, accessed March 9, 2018.

[2]Leland G. Stauber, The American Revolution, A Grand Mistake(Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2010), 187.

[3]Samuel E. Morison, Henry S. Commager, and William E. Leuchtenburg, The Growth of the American Republic – Volume 1(New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), via Google Books, 194.

[4]Nathan R. Einhorn, “The Reception of the British Peace Offer of 1778,” Pennsylvania HistoryVol. 16, No. 3, July 1949, 202, journals.psu.edu/phj/article/viewFile/21936/21705, accessed March 24, 2018.

[5]Samuel Eliot Morrison, ed., Sources and Documents Illustrating the American Revolution and the Formation of the Federal Constitution, 1764-1788(New York: Oxford University Press, 1965). Pages 176-203 provide a complete text of the instructions issued to the Carlisle Commission.

[6]Neil L. York, “Benjamin Franklin, the Mysterious ‘Charles de Weissenstein,’ and Britain’s Failure to Coax Revolutionary Americans back into the Empire,” in Paul E. Kerry and Matthew S. Holland, eds., Benjamin Franklin’s Intellectual World(Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2012), 45. I attempted to correspond with York to clarify his opinions on this and see if he had further information about it but was unsuccessful.

[7]“Charles de Weissenstein” to Benjamin Franklin, June 16, 1778, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-26-02-0574, accessed March 9, 2018.

[14]Harvard University Library Online. pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/422649875?n=1&imagesize=1200&jp2Res=0.5&printThumbnails=no&oldpds, accessed March 9, 2018. This is the digitized scan of the original police report, handwritten and in French. It somehow ended up in the papers of Arthur Lee, another member of the American diplomatic team in France. I am indebted to my multilingual neighbor, Karen Motz, for graciously agreeing to decipher the handwriting and provide the English translation, as well as some clarifications and interpretations.

[15]Benjamin Franklin Stevens, Facsimiles of manuscripts in European archives relating to America, 1773-1783, Volume XXVI (London: Malby & Sons,1889). I accessed this book at the Hatcher Graduate Library, University of Michigan. The letter, the “Plan of Reconciliation,” and “Outline of Future Government” were exhibits 835, 836, and 837 respectively. Based on the sequence of exhibits in the Stevens’ collection, 835, 836, and 837 should have appeared in Volume VIII, but a notation in that volume indicates they are included in Volume XXVI. The reason for this move in unclear. The letter itself (Exhibit 835), and Franklin’s unsent response are also transcribed and annotated in The Founders Online, but I could not find digitized versions of the attachments. I transcribed these myself from the handwritten versions.

[18]Franklin to “Charles de Weissenstein,” July 1, 1778, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-27-02-0002,accessed March 9, 2018.

[20]Massachusetts History Online. Adams Papers, Diary of John Adams, Volume 4, www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/DJA04d106, 149, accessed March 9, 2018.

[23]Police report translation, see note 14.

[29]Museum of the Jewish People – Beit Hadfutsot website, dbs.bh.org.il/familyname/weissenstein, accessed April 18, 2017.

[30]York, “Benjamin Franklin, the Mysterious ‘Charles de Weissenstein,’” 67n11. In this note, York also mentions the observation of historian Richard Reeves from the New Forest Visitors Center (Foxlease) that perhaps the “white” in Weissenstein is a reference to “the white paint used on the stucco façade of the Georgian mansion at Cox lease (now Fox lease).” Fox lease, or Foxlease, was the mansion owned by Jennings. This seems to me a stretch, but it’s possible.

[31]Franklin to “Charles de Weissenstein,” July 1, 1778, Founders Online, Footnote 4. Interestingly, Adams, writing years later, recalled that the man was named “was Col. (Mc) Fitz something, an Irish name,” demonstrating how poor historical memory can sometimes be!

[32]Sylvanus Urban, The Gentlemen’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Volume 58, Part 1 (London: John Nichols, 1788), Google Books, 372.

[33]York, “Benjamin Franklin, the Mysterious ‘Charles de Weissenstein,’” 66n10.

[34]Urban, The Gentlemen’s Magazine, 176.

[35]York, “Benjamin Franklin, the Mysterious ‘Charles de Weissenstein,’”, 67-68n20.

[36]Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, British and the West Indies: Volume 25, 1710-1711, 351-361, Originally published by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1924, British History Online, www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol25/pp351-361, accessed March 25, 2018.

[37]The History of Parliament website, www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/jennings-philip-1722-88#footnote6_pqo9q64, accessed March 25, 2018. Original source is John Almon, a bookseller and pamphleteer in this period who published registers of parliamentary sessions.

[38]Morrison., Sources and Documents Illustrating, based on my review of Commission instructions on pages 176-203.

4 Comments

Richard, thank you for a very interesting analysis of a little known incident involving the Paris Commission. Your research was excellent. May I suggest another possible objective for the note, which is purely speculative based on some understanding of British political-intelligence activities of the time: creation of conflict, and therefore some disorder within the Commission, between Adams and Franklin, and perhaps even suspicion between the Commission and the Congress had the note been taken more seriously? Not unlike the Russians today, the various British intelligence organizations were aware that creating political friction and suspicion harmed the American cause to some degree – how much is always debatable.

Ken:

That’s a good point and one angle I hadn’t thought about. Creating disorder and conflict between Franklin would not have been very difficult to do considering the highly strained relationship that already existed between the two (!), so I would say that creating some conflict between the Commission and Congress would have been a more likely target. As I mentioned, Adams had mentioned the incident to Elbridge Gerry, but not in any official capacity. I did some checking around to see if Gerry had mentioned it to others or Congress had been informed in any other way but could find nothing. This was far from a conclusive finding that no communication took place – it is hard to prove a negative – but an exhaustive review of that correspondence was a little outside the scope of the story. Another place they could have been seeking to sow distrust was in the relationship between the French and the Commission, as the letter had pretty succinct instructions on how the alliance with the French would be dissolved if the Americans accepted the British terms. Franklin defused this potential bomb by immediately coming clean with the French and essentially giving them full editorial control over how or if the letter would be responded to (the answer it turned out was not to respond).

The use of disinformation and misdirection in war is probably a topic that could be a story if not a book in itself. Washington was a master of it. As you observe, it continues in what I would term a new cold war perspective currently with the Russians. Without getting into the politics of that too much, I would only say that it, in my opinion, seems to have succeeded in disrupting domestic U.S. politics far beyond what the Russians could have hoped for in their wildest dreams (although, as between Franklin and Adams, disrupting our politics was probably not a hard task!)

Thanks for reading my article and I appreciate the feedback.

I enjoyed this intriguing piece. As to the friction between Adams and Franklin (and in this case, Washington, too), I like this exchange: Adams, “Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang Gen. Washington. Franklin electrified him with his rod, and thence forward these two conducted all the policy, negotiations, legislatures and war.” Franklin, “Adams means well for his country, is always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes and in some things, is absolutely out of his senses.”

Richard, thank you for an intriguing piece of American history. I’ve found throughout my course of study that some of the least-known events regarding the American founding are the most interesting, and perhaps might have changed history had they actually occurred.