It was a mountaintop idyll; a luxuriant bath in the affirming glow of acclaim; a sunset valediction.

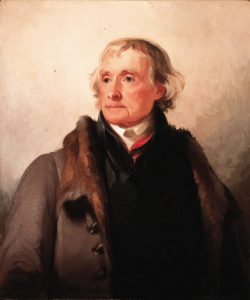

Or so it was to Saul K. Padover, who described the retired Thomas Jefferson as “that most rare of human species, a balanced and harmonious man capable of viewing the world with detached compassion and serene wisdom.” Cushioned upon the laurels thrown his way by a grateful nation, “few men in history ever achieved such philosophical balance and spiritual harmony as did Jefferson in his later – his postpolitical – years.”[1]

This was certainly the picture Jefferson painted for the outside world. Having run his race, he would spend his retirement years loathe to descend from his Monticellan paradise. Content in the bosom of his farm, family, books, and wine, “and having gained the harbor” safe from the public affairs of his country, the days remaining would be spent looking upon his “friends still buffeting the storm … with anxiety indeed, but not with envy.” Intended by nature for “the tranquil pursuits of science,” he was at long last living the life he had always desired, but that the “enormities of the times” had prevented: as a hermit atop his mountain.[2]

An intensely private man, his intensely public life – “twenty years of labor and solicitude” – had worn the statesman down. Safe finally in his study, Jefferson lamented that the “hand of time presses heavily on me. I am become feeble in body, inert in mind, and much retired from the society of the world to that of my own fire-side.”[3] His daughter Martha had been there at Monticello to meet him on his final return from Washington, and it was she who assumed the domestic leadership of her father’s household through the rest of his life. With her were over a dozen of the sage’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and amongst this miniature polity Jefferson lived “like a patriarch of old.”[4]

His daily routine began with a few hours of horseback riding throughout his plantations; the rest were mostly spent secluded in his study with the library and scientific instruments he had spent a lifetime accumulating. From this he would descend for the evening meal, take coffee, visit with family and perhaps visitors, and then retire strictly at nine o’clock.[5] Within this sheltered milieu, the “summum bonum” of his sunset years was, in his telling, an “Epicurean ease of body and tranquility of mind.”[6]

The only acknowledged blemish on this arcadia was the constant stream of correspondence invading his private study – the “affliction of my life.”[7] An old wrist injury sustained chasing (literally) a paramour during his time as minister in France made writing all the more taxing, yet however determined he was to leave the public, the public was equally determined not to leave him.[8]Up to eight hours of each day were spent with his correspondence, and “no office I ever was in has been so laborious as my supposed state of retirement at Monticello.”[9]

Much of this incoming epistolary wave solicited his opinion or involvement on various public issues. Except in rare instances, he refused, attesting to a “general aversion from the presumption of intruding on the public an opinion on works offered to their notice.”[10]

Situated, often literally, atop the clouds at Monticello, Jefferson insisted that his time amongst the world and the affairs of men should and had passed – that his last role was to watch with unruffled serenity the next generation continue the inevitable progress his had begun in the revolutions of 1776 and 1800.[11] Having famously declared to his friend and favored lieutenant James Madison that “the earth belongs in usufruct to the living,” he believed that, for all intents and purposes, he was no longer amongst the living, and must not meddle in a world that no longer belonged to him.[12] “I withdraw from all contest of opinion, and resign everything cheerfully to the generation now in place. They are wiser than we were, and their successor will be wiser than they, from the progressive advance of science.”[13]

To ensure that wisdom and progress, he took a leading role in creating the University of Virginia – an institution he had begun to envision in his years as president and that would become the “Hobby” of his final years.[14] Such a university would be based on the “illimitable freedom of the human mind,” and would be designed to “improving the virtue and science of their country,” thus insuring that succeeding generations had the manners and modes of thinking necessary for the perpetuation of republican government.[15]Jefferson would eventually gaze upon the university near his home with paternal pride; so much so that “Father of the University of Virginia” would be one of three accomplishments he requested etched into his epitaph.[16]

Aside from this, the founding father emeritus would be seen only by the family and slaves living with him at Monticello and those who visited him there – and even then only if they were fortunate. (Such was his determined isolation that Chief Justice John Marshall quipped he was “the great Lama of the mountains.”[17])

When the elevated placement of Monticello and the carefully-constructed architecture within were not enough to insure Jefferson’s privacy, he would retreat further still to his Poplar Forest property in nearby Bedford County – a property in some ways preferable to Monticello as being “more proportioned to the faculties of a private person.”[18]

Yes, to all outward appearances, Jefferson was indeed in a self-proclaimed apotheosis of sorts. Surrounded by all that he cherished, he had already begun the ascent from a leader in the Revolutionary generation to historical immortality, all the while committing himself “cheerfully to the watch and care of those for whom, in my turn, I have watched and cared.”[19]

The final climb atop his little mountain after the presidency was but the first step in this ultimate journey; a time to enjoy the comforts of a beloved patriarch while looking down upon the inevitable course of progress he and others had sacrificed so much to begin. “I have much confidence that we shall proceed successfully for ages to come.” As the new nation grew westward, so too would the rights and freedoms of man, for “it will be seen that the larger the extent of the country, the more firm its republican structure, if founded … in principles of compact and equality.” Others, but especially elder statesmen like himself, had nothing to gain from fear for the future anyway, for “the flatteries of hope are as cheap, and pleasanter than the gloom of despair.”[20]

Yet as Jefferson entered the final decade of his life, this putative hope and serenity began to sink under the weight of a darkening melancholy. The trait that had most separated him from the other most famous Founding Fathers was the idealistic lens through which he viewed the world he and they inhabited. In his personal life, he had interpreted his existence as a utopia of domestic felicity, illustrated most in the descriptive images he painted of his own retirement atop Monticello: as a contented father and grandfather living out his days in familial bliss, as a student of the Enlightenment ensconced in his library, as a dinner-host promoting the natural harmony between people over bottles of the world’s best wines.[21] This romantic optimism extended to his conception of human nature and the age in which he lived:

I am among those who think well of the human character generally. I consider man as formed for society, and endowed by nature with those dispositions which fit him for society. I believe also … that his mind is perfectible to a degree of which we cannot as yet form any conception.[22]

To him, mankind had only just entered an epoch of the sublime – a harmonious age of human interaction, scientific progress, and illimitable progress, freed at long last from a Plato’s cave of chained oppression and shadowy ignorance. Human history was now a symphony only in its first sonata.

But for Jefferson to preserve these dogmas intact inside himself required a lifetime of either ignoring or explaining away any nagging cacophonies that could have contradicted them. Many of these beliefs were castles constructed in the sky, built and maintained by borrowing against reality – or in ignoring it altogether. In the final ten years of his life, these debts would at long last come due, and it was in finally being forced to reckon with them that the illusion of his personal euphony would give way to an increasing, acute despair.[23]

Paramount among these metaphorical personal debts was his very real, very crushing financial debt. Living a life conformed to his ideals – of meticulously constructed and reconstructed estates, of libraries lined with books, of cellars stocked with fine wines – had required him to spend far beyond his means. His insolvency had always been a specter looming just within his periphery, but he had managed to keep it at bay by convincing himself that liquidating a select few of his properties, or selling “one or two full crops,” would relieve all of his burdens.[24]

It was but one of the sweet little lies he would comfort himself with throughout his life – one to which the progression of time slowly, but surely, contradicted. As his own time began to run out, it was a lie he could no longer maintain.

Having long insisted that not only did the earth “belong to the living,” and that debts contracted by one generation must be settled by that generation, he was rendered despondent at the idea of bequeathing a ruined estate to his children and grandchildren. “My own debts had become considerable,” he would complain to Madison. But instead of taking personal responsibility, he would place the blame on the need to bail out friends, on the “maintenance of my family,” and the “abject depression” of the agricultural market. To make matters worse, his saving grace – property – had “lost its character of being a resource for debts.”

In the end, he faced the prospect of selling Monticello and everything on it, and to “move thither with my family, where I have not even a log hut to put my head into, and whether ground for burial, will depend on the depredations which, under the form of sales, shall have been committed my property.”[25]

Rivalling in tone the lamentations of Job, these lachrymose sentiments came not only five months before his death, but at the end of multiple, previously unthinkable, and ultimately unsuccessful attempts to save his estate. Selling bits and pieces of his property, including slaves, had barely made a dent, and to add insult to injury, his fiscal woes were becoming increasingly public. Confronted with unavoidable failure, he was eventually left no other option than to take the humiliating step of petitioning the Virginia legislature to open a subscription lottery for his estate.[26] This not only entailed discussing the history of lotteries in Virginia, but the base need to recount his list of services on behalf of state and country.[27]

The petition was rejected.[28]

Jefferson’s debt troubles further aggravated tensions inside his own family, within which tragedy had always been close at hand. Of his six children, four had died before reaching the age of seven and a fifth, Maria (or “Polly”), had died only months after giving birth to her third child. His wife, Martha, enfeebled by a lifetime of poor health, had died shortly after the birth of their last child, Elizabeth, who herself would die three years later. These losses sent the strongest tremors through Jefferson’s carefully-maintained, idealistic world – the shocks of which often manifested themselves through extended, debilitating migraines.[29]

It was a few short years after his wife’s death that Jefferson had left his sorrows behind and sailed to France as U.S. minister. For nearly the next twenty years of public service he would mostly be an absentee paterfamilias – briefly at home, occasionally visited by daughter and grandchildren, always willing to provide written paternal counsel, but usually absent.

Upon his return to Monticello, he was confronted with a family shaken not only by the previous deaths of Martha and the children, but abuse, depression, mental illness, alcoholism, and debt. His relationship with his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph, had long been complicated. A vivid contrast in personalities (Jefferson was serene and reserved; Randolph loquacious and demonstrative), Randolph was known to grow enraged in the presence of his wife and suffered from bouts of mental illness throughout their marriage.[30] Every bit in debt as Jefferson, father- and son-in-law were able to commiserate over poor harvests and the malevolence of banks, but shared little else in common.[31] Randolph chafed under the pressure of living in the shadow of his illustrious father-in-law, while Jefferson likely resented, albeit privately, Randolph’s quarrelsomeness, alcoholism, and behavior towards Martha and the children. So poor were relations between husband and wife that Martha and their eleven children would live with Jefferson at Monticello for the remainder of his life.[32]

Always on the brink, Randolph’s life came crashing in around him after assuming the governorship of Virginia. By 1825, Jefferson’s penultimate year on earth, Randolph was not only completely gripped by alcoholism, but both personally and financially ruined.

Jefferson endeavored to bring his prodigal son-in-law back within the family fold. “I hope that to your other pains has not been added that of a moment’s doubt that you can ever want a necessary or comfort of life while I possess any thing,” he wrote. “All I have is devoted to the comfortable maintenance of yourself and the family, and to a future provision for them.”[33] Randolph could yet turn back from the path he had gone down and find happiness “by returning to the bosom of those who love and respect you, rather than to continue in solitude, brooding over your misfortunes, & encouraging their ravages on your mind.”[34]

These pleas would go unanswered, and Randolph would remain estranged from his wife and family for the rest of Jefferson’s life.

Seemingly possessed of all the qualities his father lacked, Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, would grow to become his grandfather’s favorite. Both hard-working and devoted, “Jeff” would eventually offer to personally take over the elder Jefferson’s increasingly-insolvent estate.

It came as some shock then in 1819 when Jefferson received word that Jeff had been stabbed in the streets by his grandson-in-law, Charles Lewis-Bankhead – who, like his father-in-law, Thomas Randolph, was known to abuse both alcohol and his family. Virtually estranged from the family himself, and having already been involved in a drunken altercation with Thomas Randolph at Monticello sometime before, tensions had been high between him and Jeff for some time.

No longer speaking to each other, Bankhead had nevertheless written to Jeff’s wife – an insult in the gentlemen’s code of early-nineteenth century society. When the two met in the streets of Charlottesville, Jeff’s demand for an explanation quickly resulted in a physical altercation. By the time the two were separated, Jeff was copiously bleeding and had to be carried to nearby rooms.

When Jefferson received word of Jeff’s condition that same evening, he disregarded the pleas of Martha and the grandchildren and raced via horseback to the bedside of his grandson. Once there, and seeing his feverish condition, Jefferson broke down and wept. His family, like his grandson in the bed before him, lay riven and bleeding in ways that would never fully heal. Jeff would ultimately recover; Bankhead would skip bail and abscond with his wife to a neighboring county.[35]

While dysfunction continued to shred the veneer of Jefferson’s family paradise, so too were national developments jolting the vision of America he had spent his public life maintaining – to others and to himself. In his mind, his and the Democratic-Republicans’ victory in the election of 1800 had insured that America would be an “empire of liberty,” so long as there was ample western land in which to expand. If provided this, men would be “disposed to live honestly,” provided “the means of doing so are open to them.”[36]

Jefferson had envisioned this expansion happening in a structured, patriarchal manner. One of the major ideological pet projects of his retirement years had been a “ward republic” system, whereby counties and townships in the growing republic would be divided into hundreds. In each would be a central school for the children, a justice of the peace, a constable, and a militia captain – who in their corporate whole would be charged with managing “all its concerns.” He was convinced that it was a measure of organization “without which no republic can maintain itself in strength.” Each ward would essentially be a republic-in-miniature – “a small republic within itself, and every man in the state would thus become an acting member of the common government, transacting in person a great portion of its rights and duties.”[37]

It was also an extension of the family structure practiced at Monticello (in theory, at least): a patriarchal figure at the head benevolently caring for the affairs of children, children-in-law, and grandchildren below him.[38]

Yet as with his family, socio-political realities in the United States disappointed Jefferson’s expectations. Instead of a republic of mini-republics governed by enlightened patriarchs akin to himself, American democracy in the first decades of the nineteenth century was becoming a rough-and-tumble, coarsened expression of the ordinary man. Less and less was it a Jeffersonian “empire of liberty” governed by genteel, wine-sipping, enlightened patriarchs; but more the bristly, whiskey-swilling common-man that would come to represent Jacksonian democracy – or rapacious northern, urban, speculators, bankers, and money-men akin to his old foe Hamilton.[39]

By his final decade, the man who had entered retirement expressing a serene assurance about the next generation could hardly contain his disdain for it. Not only was the federal government encroaching upon the states, but America’s young men, “who, having nothing in them of the feelings or principles of ’76, now look to a single and splendid government of an aristocracy, founded on banking institutions, and moneyed incorporations under the guise and cloak of their favored branches of manufactures, commerce and navigation.”[40] Aiding and abetting this was an anti-republican judiciary, “a subtle corps of sappers and miners constantly working under ground to undermine the foundations of our confederated fabric.”[41]

Of greatest alarm to Jefferson was the increasingly toxic nexus between one of his most cherished articles and his life’s most obvious contradiction – between western expansion and slavery. Shattering the veneer of national comity and the “Era of Good Feeling,” Missouri’s petition to enter the Union as a slave state at long last brought to the forefront the issue the founding generation had worked tirelessly to delay.

This had suited no one more than Jefferson, who never missed an opportunity to lament slavery’s existence and hope for its abolition – but who also was personally dependent on the labor and value that “species of property” provided him.[42] For his entire life, no one had wished “more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of [slaves’] body & mind to what it ought to be.”[43] But though emancipation would always be his most “fervent prayer,” he had always foresworn any personal efforts to see its fulfillment.[44] Reassured that “the hour of emancipation is advancing, in the march of time,” he avowed a gradualist approach – emancipating slaves born after a certain day – which would “lessen the severity of the shock which an operation so fundamental cannot fail to produce.”[45] This path would also have the singular advantage of taking place long after he was gone.

The “Missouri Question” eviscerated this idea, and was received “like a fire bell in the night.” So alarmed was Jefferson that he “considered it at once as the knell of the Union.” Despite his long-held belief that allowing slavery to spread into the incoming western territories and states would gradually diffuse it, it brought to the surface all the gaping cleavages between north and south swept under the rug for the previous four decades. As it stood now, he complained that “we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” The generation he had long placed such assured faith in was now responsible for the impending demise of the union he had helped create. “I regret now that I am to die in the belief, that the useless sacrifice of themselves of the generation of 1776 … is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons.”[46]

The last cornerstone in Jefferson’s castle in the sky had begun to crumble, and with it came the very structure itself. No longer able to hear only the harmonies of domestic utopias, an enlightened posterity, and an expanding empire of liberty, America’s aging apostle of liberty was being mugged by harsh realities and impatient contradictions. He could no longer pay these illusions forward any more than he could his own debts, and the sorrow therein began to come out through his correspondence as much as the traditional Jeffersonian themes.

As the Missouri crisis passed and America once again managed to push the issue of slavery further into the future, Jefferson slowly walked back from his apocalyptic bodings.[47] But the bloom had fallen, and a naïve innocence he had maintained for most of his life had been lost forever. In those final years of his life, he had had to confront the bitter reality that the world – his world – did not exist as he would have had it exist in the spaces between his own mind and his voluminous writings. In this personal, painful reckoning, Jefferson’s last years were much less a fulfillment of the Jeffersonian vision he left us on paper, and had convinced himself of through the course of his eight decades, than an intensely painful, private funeral for the death of his own grand illusions.

Thomas Jefferson gave his last breath on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence – surrounded by the books, slaves, and contradictions he had always tried to keep at bay. Those contradictions, most especially that between the America he envisioned in the Declaration and the one that truly existed, would live on for far longer.

[1]Saul K. Padover, Jefferson: A Great American’s Life & Ideas (New York: Mentor, 1952), 159.

[2]“Thomas Jefferson to P.S. Dupont de Nemours, 2 March 1809,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: Writings(New York: The Library of America, 1984), 1203-1204.

[3]“Thomas Jefferson to Madame de Corny, 2 March 1817,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified February 1, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-11-02-0115.

[4]Thomas Jefferson to Maria Hadfield Cosway, December 27, 1820,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1711.

[5]“Daniel Webster, Notes of Conversation with Thomas Jefferson, 1824,” in John P. Kaminski, ed., The Founders on the Founders: Word Portraits from the American Revolutionary Era (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 318.

[6]Jefferson to John Adams, June 27, 1813,” Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6076.

[7]Jefferson to Charles Willson Peale, March 16, 1817,” Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-11-02-0155.

[8]For a brief discussion of the romance between Jefferson and Maria Cosway in France, see Fawn M. Brodie, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974), 29. For the feelings Jefferson had for Mrs. Cosway, see his famous “Dialogue Between My Head and My Heart” epistle in Jefferson to Cosway, October 12, 1786,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-10-02-0309.

[9]Jefferson to William A. Burwell, February 6, 1817,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-11-02-0038.

[10]Jefferson to Joseph Delaplaine, December 25, 1816 (first letter),” Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-10-02-0475.

[11]Jefferson would always insist that his and the Democratic-Republicans’ sweeping victories in the election of 1800 was every bit the victory over monarchists and “Anglomen” the War of Independence had been. To him, the “revolution of 1800” was “as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 1776 was in its form.” See “To Judge Spencer Roane, September 6, 1819,” in Jean M. Yarbrough, ed., The Essential Jefferson(Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2006), 250. See also “Jefferson to Governor John Langdon, March 5, 1810,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1218.

[12]Jefferson to James Madison, September 6, 1789,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-15-02-0375-0003. See also, “Jefferson to Major John Cartwright, June 5, 1824,” in Petersen, ed.,Writings, 1493. Technically, Jefferson attempted one last foray into public affairs in the last year of his life: a response written on behalf of Virginia rejecting President John Quincy Adams’ proposed internal improvements on Constitutional grounds. Submitted to Madison for approval, his former lieutenant and successor advised him not to make it public. See Jefferson to Madison, December 24, 1825,”Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5763.

[13]For comments on earth belonging “to the living”, see Jefferson to Madison, September 6, 1789,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-15-02-0375-0003. For his determination to defer to the “generation now in place,” see “To Roane,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 252.

[14]“Jefferson to John Adams, October 12, 1823,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1479.

[15]Thomas Jefferson to William Roscoe, 27 December 1820,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1712. Jefferson to Cosway, October 24, 1822,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3111.

[16]“Epitaph [1826],” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 706-707.

[17]“John Marshall to Joseph Story, September 18, 1821,” in Kaminski, ed., Founders on the Founders, 316.

[18]Jefferson to John Wayles Eppes, September 18, 1812,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-05-02-0292.

[19]“Jefferson to Benjamin Waterhouse, March 3, 1818,” in Kaminski, ed., Founders on the Founders, 316.

[20]“Jefferson to Francois de Marbois, June 14, 1817,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1410-1411.

[21]Geoff Smock, “Exploring Thomas Jefferson’s Love of Wine.” Journal of the American Revolution. August 28, 2016, accessed April 09, 2018, allthingsliberty.com/2016/08/thomas-jefferson-love-wine/.

[22]“Jefferson to William Green Munford, June 18, 1799,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 194.

[23]For an authoritative interpretation of the dichotomy between the ideals and realities in Jefferson’s life, and how he maintained them, see Joseph J. Ellis,American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson(New York: Vintage Books, 1998).

[24]Brodie, An Intimate History, 455-457. For his stated assurance that he could solve his debt through his agricultural products at Monticello, see Jefferson to Archibald Robertson, April 25, 1817,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-11-02-0247.

[25]“Jefferson to James Madison, February 17, 1826,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1514-1515.

[26]See “Broadside: A Plea for Financial Assistance by Subscription for Thomas Jefferson, 1825, December 31, 1825,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5787.

[27]“Thomas Jefferson’s Thoughts on Lotteries, ca. January 20, 1826, Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5845.

[28]Thomas Jefferson Randolph to Jefferson, February 3, 1826,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5875.

[30]Brodie, An Intimate History, 280-281.

[31]“There seems to be so general a sickening at the effects of the banks,” Jefferson would write to him, “that I hope the country is ripe for suppressing them by degrees.” Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, August 9, 1819,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-0673.

[32]Brodie, An Intimate History, 457-458.

[33]Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, June 5 1825,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5282.

[34]Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, July 9, 1825,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-5369.

[35]Alan Pell Crawford, Twilight at Monticello: The Final Years of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Random House, Inc., 1998), xxiii-xxvi; 162-169.

[36]For Jefferson’s “empire of liberty” quote, see Jefferson to Benjamin Chambers, December 28, 1805,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-2910. For his Americans being “disposed to live honestly” see “Jefferson to Francois de Marbois, June 14, 1817,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1410-1411.

[37]Jefferson to John Cartwright, June 5, 1824,” Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-4313.

[38]For an exemplary examination of Jefferson’s patriarchal conceptions of both familial and political society, see Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf, “Most Blessed of Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of Imagination (New York: Liveright Publishing Corp., 2016).

[39]Gordon S. Wood, Revolutionary Characters: What Made the Founders Different (New York: The Penguin Press, 2006), 114-115.

[40]“To William Branch Giles, December 26, 1825,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 271.

[41]“To Thomas Ritchie, December 25, 1820,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1446.

[42]The phrase “that species of property” was a common euphemism used by the leading members to refer to the institution of slavery. See Jefferson to Charles Clay, July 1, 1816,”Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-10-02-0112. George Washington would use the phrase in his correspondence several times. See George Washington to John Francis Mercer, December 5, 1786,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-04-02-0380; and Washington to Benjamin Dulany, July 15, 1799,” Founders Online,http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0156.

[43]“To Benjamin Banneker, August 30, 1791,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson, 181.

[44]“To James Heaton, May 20, 1826,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1516.

[45]“To Edward Coles, August 25, 1814,” ibid., 1345.

[46]“To John Holmes, April 20, 1820,” ibid., 1434. See also, Jefferson to William Short, April 13m 1820,” Founders Online,founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1218.

[47]See “To Henry Lee, May 8, 1825,” in Yarbrough, ed., Essential Jefferson¸267-268; and “To Roger C. Weightman, June 24, 1826,” in Peterson, ed., Writings, 1516-1517.

4 Comments

I visit Poplar Forest outside of Bedford, Va. every chance I get. This was Jefferson’s mountain get-away where he escaped Monticello from Cornwallis’s attack on his home. This was where he would spend summer with his grandchildren. The house is a currently being restored and it is a wonderful place to visit set in a beautiful bucolic setting. I encourage anyone interested in Jefferson not to miss it.

That was a beautifully written article, flowed along just perfectly with TJ’s wondrous quotes.

My first thought after the article was my gosh farming is just such hard work, and Charlottesville is not close to a big marketplace or port. Yet it sure is a beautiful spot in the world. I read a book about Commodore Uriah Levy and how he was so dedicated to and instrumental in saving Monticello years after TJ’s passing. It referenced how much of a destination for people to visit Monticello esp after Jefferson left office and that no one was ever turned away. Which means he they had to feed and often house guests. Clearly the man could not get peace and quiet because he was one of the most famous men in the world.

The Uriah Levy book was such an interesting read. He also commissioned in 1834 the amazing bronze statue of TJ that is in the Capital rotunda today. All the great bronzes come from France, his statue is no exception. Also I found this particularly key, all of the other statues in the Capital are tax-payer funded – only the TJ bronze was privately funded – by Commodore Levy. 🙂

Excellent article! Those who are studious students of Jefferson like me, I the book “Jefferson’s secrets: death and desire at Monticello, which is all about his retirement.

Excellent article about a fascinating and enigmatic individual. Jefferson will continue to mesmerize Americans for years to come.