In the fall of 1777, the Continental Congress had reached one of its most desperate points of the American Revolution. In September of that year George Washington had been defeated by the forces of Sir William Howe at Brandywine, the Battle of the Clouds, Paoli, and Germantown. Because of this failure the British captured the American capital of Philadelphia, and began an occupation of the city that would last nine months. In the days before Howe’s arrival, Congressmen became fugitives and scattered to the Pennsylvania countryside to avoid capture. Though they abandoned the city, there was no intention amongst the delegation of abandoning the young republican government. After a brief stint in the city of Lancaster (which served as the American capital for precisely one day) the Continental Congress took up residency across the Susquehanna River in York, Pennsylvania. They would spend the next nine months in exile from Philadelphia.

Although the Patriot cause was stunned by the loss of its capital city, the congressional delegates in York continued their struggle to solve some of the nation’s most dire problems. From the halls of York’s rough-hewn courthouse would emerge a first draft of the Articles of Confederation, and critical treaties of alliance with the empire of France. But their successes were not without failures, and nowhere was this more visible than among the ranks of the Continental Army. For much of their time in York, General Washington had struggled to place his army between the vulnerable Congress and Howe’s army in Philadelphia. He would ultimately settle on Valley Forge, and once in place an intensive correspondence between the general and his civilian overseers commenced. They spoke of many issues, but the one underlying theme was Washington’s constant need for provisions.

Since the beginning of the conflict the Patriot army had been undersupplied. While a lack of footwear and clothing, and expiring enlistments often overshadow its other needs, one of the most urgent deficiencies remained munitions. Of their most pressing concerns was a want of lead, sorely needed for the creation of musket balls. Since 1775 the Continentals had relied on imported lead, but a combination of a British blockade and frequent combat had dwindled its supply. By October of 1777, in the wake of the disasters of the previous month, the disparity had become critical. In August Congress requested that all of Philadelphia’s lead-based downspouts be removed and turned over to the army.[1]

On October 30, Congress “Resolved … That a letter be written by the Board of War to the government of the state of New York, representing, in the strongest terms, the great want of lead, the absolute necessity there is for providing seasonable resources of that article.” The resolution continued by demanding that New York should “forthwith … take measure for having lead mines in that State worked …” and offered that if labor was scarce, “a competent number of prisoners of war” should be supplied to fill the need. It was a dramatic step taken by a Congress on its proverbial heels. With no further reliable importation of lead expected and most domestic sources exhausted, the delegates asked one of its member legislatures to fund a highly speculative mining operation. Although the need was undeniable, the request fell on deaf ears in New York. The delegates of the Continental Congress were hungry for a new source of the essential mineral, and their attentions would soon turn to the Pennsylvania frontier.[2]

The Sinking Spring Valley

On February 28, 1778 Maj. Gen. John Armstrong penned a note to Thomas Wharton, Jr, President of Pennsylvania, stating, “there appears to be a Scarcity of the important article of Lead …” He continued by stating that he knew of a region famous for its lead deposits in the wilds of Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains. The area was a lightly populated expanse known as the Sinking Spring Valley, and in it was a “Lead Mine, situate in a certain Tract of Land … formerly surveyed for the use of the Proprietary Family.” In a follow-up letter Armstrong added that “the mine is comprehended by lines run for the Proprietaries … if I remember right, as the year -61.” By 1778 Armstrong had been well acquainted with the region, and his intimate familiarity was a testament to the twisting political loyalties of a Colonial America in revolt.[3]

In the 1750’s John Armstrong was a trusted agent of the Penn Family. As the colony of Pennsylvania was a proprietary colony, the Penns held near total control over the land and its titles. While the colony was famous for its diverse demographic makeup, squatters and settlers from across the European continent flooded its backcountry and claimed large swathes of land for themselves. In this fluid world, the Penns most potent weapon in a potential land dispute was a highly skilled surveyor – enter John Armstrong.

Born in Ireland, Armstrong was a master land specialist who had laid out the boundaries for the new Cumberland County and its seat of Carlisle in 1750. In 1755 Armstrong oversaw the construction of a military road in support of Gen. Edward Braddock’s march on Fort Duquesne, and in 1756 he earned his first military accolades by leading a raid deep into the wilderness against the Ohioan village of Kittanning. Armstrong’s travels and experiences had given him a deep knowledge of the Pennsylvania frontier, and he was unlikely to have overlooked a massive mineral deposit which he identified as being “not far from Frankstown.” The Frankstown Path was a veritable Indian superhighway of the eighteenth century which was well travelled by natives and speculators alike; Armstrong himself passed the 9,000 acre Sinking Spring Valley en route to and from Kittanning in 1756.[4]

Mining in the Sinking Spring Valley, a triangular valley made up of the sharply converging ridges of Brush Mountain and covered in dense forest, would not be easy. His prior experience in the west had shown Armstrong just how stubborn a migrant squatter could be; as the general himself was of Scots-Irish descent, he expected a fight from those that had illegally cleared and farmed the land. He stated this plainly in his letter to Wharton. He wrote “the Mine ought … be seized by, and belong to, the State, and the Private persons who without right may have sat down on that reserved Tract, shou’d neither prevent the present use of the Lead, nor be admitted to make a monopoly of the Mine.”[5]

Roberdeau’s Mission

Following Armstrong’s recommendation, on March 18, 1778 Pennsylvania congressional delegate Daniel Roberdeau officially petitioned the state assembly for the undisputed title to the lands in the Sinking Spring Valley. With the loyalties of the Penn family attached to the Crown, Roberdeau sensed an opportunity to both enrich himself and the fortunes of the Continental Army. While the matter of land title remained in question, the Pennsylvania Assembly punted on the issue, but went so far as to agree to compensate the Congressman for any losses that he might sustain should his mining operations fail. Resolving “that the utmost encouragement should be given to opening the said mine and smelting the ore therein for public benefit, will indemnify the said Daniel Roberdeau … for any loss they have already sustained or may sustain … if they shall immediately proceed upon the said work.” As a matter of business this guarantee was not ideal, but given the vulnerable status of the revolutionary movement it was likely the best that he could have hoped for.[6]

Roberdeau was a familiar face to many of the Pennsylvanians, and was recognized as one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest merchants before the war began. At fifty years old, Roberdeau was a colonial success story, amassing most of his fortune in the lumber trade. He served in the Colonial Assembly from 1756 to 1760, and joined the Continental Congress in 1777. In November of that year Roberdeau found himself on a congressional committee engaged in accruing sorely needed supplies for Washington’s army. By the spring of 1778 it appeared that Roberdeau’s previous business experience combined with the specific details of the government’s deficiencies put him in a unique position to personally confront the nation’s lead scarcity. By April 11 Roberdeau had been given a leave of absence from his Congressional duties, and began accruing supplies and manpower for the trek into the wilderness.[7]

As the unofficial capital of the Pennsylvania frontier, the town of Carlisle was the obvious launching point for Roberdeau’s expedition. In a letter to Wharton dated April 17, Roberdeau opined on his future endeavors and outlined many of the challenges that he would face. “My views have been greatly enlarged since I left York … for the public works here are not furnished with an ounce of lead by what is in fixed ammunition.” He further explained that he expected to meet resistance from local bands of Loyalists and their Indian allies. He understood that skilled labor would be in short supply, and planned the “erection of a Stockade Fort, in the neighborhood of the Mine I am about to work; if I could stir up the Inhabitants to give their labour in furnishing an Asylum for the Familiar in case of imminent danger …” Although he was an outsider to the region, he hoped that his efforts would be well-received and that he would “not be suspected of any sinister design.”

Daniel Roberdeau was not the only one with high hopes for the mission. In his April 26 general orders, Commander-in-Chief George Washington requested “Two good smelters, two ditto Miners, four Ax men, One dresser … to burn ore and a good smith …” to aid in the lead mining operation in the Sinking Spring Valley. Likewise Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates also expressed an interest in the project. “We have given every Encouragement to the Opening & working a valuable Mine on the Juniata in this State which from present Appearances is sufficient to supply all America.” Again harkening back to the titles and rights to the land, Gates admitted “there are some Disputes about the Property which we fear will embarrass Matters much.”[8]

Initial Woes

At the outset of his arrival in the Sinking Spring Valley, Roberdeau faced many great obstacles. Because of the nature of the war on the frontier, the valley’s residents lived under near-constant fear of being raided by Loyalists and their native allies. Like most of the Ohio Country and western New York, these bands struck quickly with partisan fervor and left many settlements in a state of ruin. For the congressman from Philadelphia, this was a drastic change from his wartime experience in the east. He wrote, “The insurgents from this neighborhood I am informed are about thirty … it appears that this banditti are expected to be joined by 300 men from the other side of the Allegheny; reports more vague mention 100 whites and savages …” To combat this Tory threat, he accrued a company of approximately forty rangers from Bedford County as well as ten Continental regulars. Like his men, the full horrors of a revolution in the west were apparent to Roberdeau almost immediately. On the way they witnessed “a most distressing sight, of men, women, and children, flying through fear of a cruel enemy.”[9]

Roberdeau’s expedition was not an easy one, and it was complicated by the logistics of mining in a war zone. Along with locating an actual source of lead, he also needed to find a location that would allow for the construction of a fortification. Both goals were achieved very soon after his arrival in the valley, but acting on them proved to be a terrible challenge. On April 27 Roberdeau wrote to President Wharton that the rumors of a massive lead deposit were in fact true. “I am happy to inform you,” he began, “that a very late discovery from a new vein promises the most ample supply … to the army.” In many ways Roberdeau’s mission reveals the geological history of Central Pennsylvania. The region of the Sinking Spring Valley was rich in lead, but also zinc and other valuable minerals. Locating these deposits was quite easy; mining them, however, would prove to be far more difficult. Offsetting the good news of his discovery, the congressman delivered the bad news to his patron. “I am very deficient in workmen,” he wrote. Of the forty rangers that Roberdeau could recruit in the east, he estimated that “at most 7” had remained. While it was a terrible blow to his morale, these sorts of desertions were not uncommon among frontier militias. Many volunteers had obligations at home, and by late April the planting season was well under way on many settlements. Although they may have signed up with enthusiasm, the rangers had far more pressing matters waiting for them on the on the home front.[10]

A great deal of mystery remains regarding the laborers of the Sinking Spring Valley. While the congressman was shorthanded at the outset, successful mining operations would be maintained throughout 1778 and 1779. His initial situation was so precarious that Roberdeau even petitioned George Washington for assistance. “I am ever loath to intrude on your Excellency,” he began meekly,

therefore permit me to inform your Excellency that the want of Smelters of lead is the only remora now in the way of supplying your Army in the most speedy & ample manner with that necessary Article, now transported from distant parts of the Continent, from a vein of Ore in this State, within nine miles of the navigation of a branch of Juniata. A large quantity of Ore is at the pits mouth, a mill for stamping constructed, & a Furnace will be finished, I expect within ten days from this time, but Artificers of the above Class are so scarce in this young Country, that having tryed to obtain them by advertising and from Deserters from the Brittish Army, I am at length constrained reluctantly to trouble you on the Subject.”[11]

The general replied “The number of applications for manufacturers and artificers of different kinds could they all be complied with, would be a considerable loss to the army …” Washington noted that “as the establishing the smelting of lead is of very great importance, I have directed Serjeant Harris to repair to you at York Town; and this day given general orders for an inquiry to discover if two others, who understand this business can be found in camp.” In Roberdeau’s April 17 letter to Joseph Wharton, Jr, seeking a solution to his labor deficiencies, he again asked for “smelters and Miners from Deserters from the British Army.” It is uncertain whether these requests panned out into the actual assignment of workers to the Sinking Spring Valley, but later accounts in The Columbian Magazine from 1788 verify that “the miners were all oldcountrymen, utterly unused to this mode of life …”[12]

This could be an indication of British or German prisoners of war being enlisted into Roberdeau’s mining service following requests to both Washington and Wharton. Given Pennsylvania’s long history of ethnic diversity and steady flow of immigrants throughout the eighteenth century, it is also possible that these “oldcountrymen” were recent arrivals seeking gainful employment in the west. Whether they were German or Scots-Irish, such workers would have been in ready supply. Wherever these unnamed laborers originated, previous historical analysis by Darwin Stapleton of the University of Delaware speculates that Roberdeau’s mining operations maintained between thirty and forty workers during its operation from 1778 to 1780.[13]

The Lead Mine Fort

From his earliest conceptions of the mission Daniel Roberdeau had envisioned a stockade fort in the Sinking Spring Valley. This was done for two important purposes, both of which could be viewed as self-serving. First, it would provide shelter from Indian raids for the families of the region and act as a show of good faith to curry local favor. Secondly, it would require at least a minimal military commitment in the form of manpower from the state or federal government. Both would give the public some type of stake in the mission, and underwrite any potential losses that Roberdeau could personally incur.

Daniel Roberdeau was a wealthy man and, by nature, a creature of the east. He was a member of the Continental Congress and only granted a finite leave of absence to oversee the beginnings of a lead mining operation in the Sinking Spring Valley. Thus, after less than a month in the wilderness, Roberdeau returned to York. While the precise date of his departure is not known, a letter written by Roberdeau after rejoining the Continental Congress in York dated May 23 is the earliest presently identified. As a prominent capitalist he was accustomed to managing distant affair from afar, and likely saw this mission in the same light. As previously stated he had been corresponding with Washington as late as June regarding his initial labor challenges. Thus, before he departed from the mountains, Roberdeau delegated military authority to Major Robert Cluggage of the Bedford County militia. In his June 4th letter to Washington, the congressman stated, “I left Major Robt Clugage a discreet Officer in Command with about seventy men chiefly Militia, with a few Continental Troops raised to serve until the 1st Decr next.” Under the watch of Cluggage much of the construction of the stockade named “Fort Roberdeau” would be completed, although it was locally referred to as “the Lead Mine Fort.”

Fort Roberdeau was not built from a single design into its final form. Like most frontier outposts, it initially began as series of cabins to protect workers and house its garrison. Over time this would develop into the recognizable stockade fort that has become so synonymous with eighteenth century warfare in North America. As Roberdeau stated in his June 4 letter to Washington, “To prevent the Evacuation of the frontier of Bedford County and, for the general defence against Indian incursions I have built with Logs at the Mine in Sinking Spring Valley at the foot of Fisher Mountain, a Fort, Cabbin fashion, 50 yds square with a Bastion at each Corner. The Fort consists of 48 Cabbins about twelve feet square exclusive of the Bastions.”[14]

When eventually completed the outpost was a four-sided bastioned structure. Fort Roberdeau was unique as it was complete with a large furnace and towering chimney specifically designed for the smelting of lead as well as several outbuildings used later in the process. Placed in a clearing and surrounded by towering mountain peaks and ridges, the fort also contained a design feature rarely seen on the colonial frontier. Instead of its outer rampart consisting of vertical logs driven into the ground, Fort Roberdeau’s instead lay horizontally. Due to the mineral rich nature of the Sinking Spring Valley, the location of the fort sat directly atop a dense bed of limestone. For Daniel Roberdeau’s expedition the valley was both a gift and a curse; there was a plentiful supply of rich mineral wealth present, but the limestone bottom was so unwieldy that it was impossible to build a fort in the conventional way.[15]

Breaking Ground

With the initial successes of locating workmen for his smelting operations, Daniel Roberdeau’s mines were producing lead by the summer of 1778. Using the Juniata River to transport the refined ore, the congressmen’s preliminary assessment that the mineral was readily available appeared to have been accurate. According to the Columbian Magazine, the Roberdeau expedition mined at multiple simultaneous locations with mixed results. While these accounts do provide an order or timeline, they do offer clues regarding the unique characteristics of each mine. One of the earliest places which Roberdeau’s men began to dig was just outside of the walls of the Lead Mine Fort, which leads to the sensible conclusion that this was likely the site of the first mine. “Several regular shafts were sunk to a considerable depth,” it read. “One of which was in the hill, upon which the fort was erected, and from which many large masses of ore were procured; but because it did not form a regular vein, this was discontinued.”

A second mining operation was began “about one mile from the fort, nearer to Franks-town,” the article continued. This description was far more detailed, and as the author asserted that the “miners continued until they finally relinquished the business,” in all likelihood this was one of the most productive mines encountered.

When they first began they found in the upper surface or vegetable earth, several hundred weight of cubic leadore, clean and unmixed without any substance whatever, which continued as a clue, leading them down through the different strata of earth, marl, &c. until they came to the rock , which is here in general of limestone. The shaft first opened was carried down about 20 feet; from which a level was driven about 20 or 30 yards in length, towards the Bald Eagle Mountains; but as strong signs of ore were observed behind the first shaft, it gave occasion to sink another, which fully answered every expectation; and when they had arrived to the depth of the first level, they began to drive it into the first shaft, intending as soon as they had formed that opening, and cleared it of ore, to begin a shaft lower down; the vein of ore shewing itself strongly upon the bottom of the old level.

A third mine was started on a barren patch of treeless ground described as possessing “a long grass which soon turns yellow and perishes, exhibiting a strange contrast to the other parts surrounding it. The upper earth is composed of a fine mold, and so excessive black as to create a strong suspicion of a large body of ore being under it.” The article described a great deal of problems with this shaft including crumbling limestone and flooding. It was “soon quitted, as being too wet and swampy.” These harsh realities on digging in the depths of the Pennsylvania wilderness continued to plague Roberdeau’s men when a fourth shaft “was continued with much success to the depth of about 12 feet, until the fall of an heavy rain filled the springs so as to prevent any further discovery.”[16]

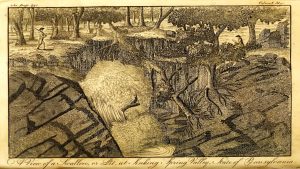

The exact refinement process of the raw mineral into a usable byproduct remains uncertain. In his 1971 article, Stapleton posits that the lead ore was broken into more manageable quantities and washed. It then would be smelted and “run into sand moulds of pigs small enough to be transported by horse or mule” before being floated down the Juniata River. A careful examination of the of the Columbian Magazine engraving from December 1788 reveals several outbuildings and milling equipment that would have served this process well.[17]

Conclusion

For all of his efforts and expenses, Daniel Roberdeau saw no major return on his personal investment. After his initial return from his first foray into the west, Roberdeau petitioned the Pennsylvania Assembly for a near immediate refund for his original start-up costs of his expedition, writing “it would be of great service, as my late engagement in the Lead works has proved a moth to my circulating Cash and oblige me make free with a friend in borrowing; I hope to congratulate you soon on regaining our Capital.” With no luck squeezing any funds from the body, he would later pen a letter to the recently appointed President of Pennsylvania Joseph Reed seeking satisfaction. The amount of lead produced, listed as “ten hundred pounds,” was said to have been delivered “some Months ago.” Roberdeau believed that “six Dollars demanded for lead” was a fair amount, and that his “advances are insupportably great.” He further politicized his plight by claiming that all mining operations had ended, and that it was “entirely thro default of Congress in not furnishing the necessary defenses.” With that pronouncement it could be concluded that lead mining operations in the Sinking Spring Valley had ceased entirely in the fall of 1779.[18]

Whether Daniel Roberdeau was ever paid for his service remains unknown; his lead mines were likely a total financial loss. That said, his impact on the frontier was a positive one. Despite his absence, Fort Roberdeau remained a valuable sanctuary for the families of the region, and his mines validated the richness and future prosperity of the Sinking Spring Valley mineral deposits. Treaties with France remedied the army’s need for supplies and munitions, but the lead mining operations organized by Daniel Roberdeau reveal the industrious spirit of the American Revolution during one of its most challenging periods.

[1] Journals of the Continental Congress, vol. 8 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 677.

[2]Journals of the Continental Congress, vol. 9, 847.

[3] John Armstrong to Joseph Wharton, February 28, 1778, Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, vol. 6, (Philadelphia: Joseph Severns and Co, 1853), 293-294; Armstrong to Wharton, April 13, 1778. Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, vol. 6, 412-414.

[4] For the most detailed study of Armstrong’s life, see William W. Betts, Jr., Rank and Gravity: The Life of General John Armstrong of Carlisle (Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 2011).

[5] Armstrong to Wharton, February 28, 1778

[6] Roberdeau Buchanan, Genealogy of the Roberdeau Family (Washington: Joseph L. Pearson, 1876), 82.

[7] Buchanan, Genealogy of the Roberdeau Family, 79; Journals of the Continental Congress, vol. 10, 1778.

[8] General Orders, April 26, 1778, and Horatio Gates to George Washington, April 29, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives.

[9][9] Daniel Roberdeau to John Caruthers, April 23, 1778, Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, vol. 6, 436-437.

[10] Roberdeau to Wharton, April 23, 1778, Ibid., 6, 422-423.

[11] Roberdeau to Washington, June 4, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives.

[12] Washington to Roberdeau, June 15, 1778, The Writings of George Washington, vol. 12, (Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, 1839), 65-66; Roberdeau to Wharton, April 17, 1778, The Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, vol. 6, 422-424; The Columbian Magazine, September, 1778, archive.org/stream/columbianmagazin21788phil#page/n719/mode/2up), 489-492.

[13] Darwin H. Stapleton, “General Daniel Roberdeau and the Lead Mine Expedition, 1778-1779,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies Vol. 38, No. 4 (October, 1971), 361-371.

[14] Roberdeau to Washington, June 4, 1778.

[15] Stapleton, “General Daniel Roberdeau,” 366-368. For a detailed engraving of Fort Roberdeau, see The Columbian Magazine, December 1778, 702-703.

[16] The Columbian Magazine, September, 1778. 489-492.

[17] Stapleton, “General Daniel Roberdeau,” 368-369.

[18] Roberdeau to George Bryan, June 6, 1778, Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, vol. 8, 584.

Roberdeau to Joseph Reed, November 10, 1779. Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, vol. 8, 6-7.

2 Comments

Thank you for writing this article.

You stated, “Fort Roberdeau was not built from a single design into its final form. Like most frontier outposts, it initially began as series of cabins to protect workers and house its garrison”

The fort was built as a cabin fort, which means the back wall of the cabins was the outside wall of the fort.

“I have built with Logs at the Mine in Sinking Spring Valley at the foot of Tushes Mountain, a Fort, Cabbin fashion, 50 yds. square with a Bastion at each Corner. The Fort consists of 48 Cabbins about twelve feet square exclusive of the Bastions”

48 cabins at 12 feet square with the back wall being part of the fort means that the initial cabins were literally built into a large planned structure. This is very different from fortified homesteads, often called forts or blockhouses, which often evolve from pre existing cabins.

When the fort was rebuilt for the bicentennial many things were not known, including the size of the fort. The smelter was based on the evidence of a chimney of a free standing structure inside the fort in an etching from 1789. Is it stated anywhere that that chimney was a smelter?

The Chimney/Furnace conclusion does not agree with primary sources. The chimney in the image being a furnace has been a hypothesis by several people in the past. It is only an assumption that a building inside the fort is the smelter. I have not seen any primary documentation verifying it. There is strong primary evidence that points in another direction.

There are several places in documentation that water dependent blast furnaces are mentioned. Two blast furnaces are discussed, one of which stopped working for a time.

Blast Furnace being constructed:

http://fortroberdeau.org/dispatch/timeline/1778-11-09-daniel-roberdeau-to-nathaniel-owings/

A blast furnace is mentioned in William Henry’s letter concerning the failing lead operations. One of the focuses of this letter is the lack of water needed to run the smelting and ore processing.

http://fortroberdeau.org/dispatch/1779-05-10-report-lead-mine/

What was reconstructed at the fort is not a blast furnace, and is based on much earlier technology.

A note on German vs British POWs serving at the fort. While there is documentation of the fort requesting German POWs, there is only evidence of one set of prisoners working at the fort. They were British, as is noted in the letter below.

http://fortroberdeau.org/dispatch/timeline/1778-11-09-daniel-roberdeau-to-nathaniel-owings/

York County’s colonial courthouse was not “rough-hewn,” but rather a substantial brick structure. The York County History Center (www.yorkhistorycenter.org) now offers tours of a replica of that building.