There was no turning back after the morning of April nineteenth.[1] When the militiamen under Captain John Parker defended themselves against the British regulars at Lexington, they signaled a transition in the imperial crisis. What was still primarily a war of words before the sun broke the horizon that morning in 1775 had intensified into an armed conflict by the falling of that evening’s shadows. Meeting in Philadelphia shortly after this bellwether moment, the ruling body of the Presbyterian church, the Synod of New York and Philadelphia, wrestled alongside their fellow colonists with the repercussions. In the course of their annual meeting the synod decided to write a pastoral letter to the congregations under their care and throughout the colonies.[2]

This letter set out four things very clearly. First, God was still sovereign in all things, and that “affliction springeth not out of the dust,” meaning, in other words, it was time to examine themselves and repent. Second, the synod insisted that they were still, and should be, loyal British subjects who hoped for reconciliation and peace. “Let it appear,” they wrote, “that you only desire the preservation and security of those rights which belong to you as freemen and Britons, and that reconciliation upon these terms is your most ardent desire.” Third, they affirmed that the elusive theory of justifiable rebellion was well within reach. If “the British ministry shall continue to enforce their claims by violence,” then Presbyterians should fight, alongside the rest of the colonists.[3] Fourth, the synod noted that while the conflict lasted its members needed to maintain colonial unity by both supporting the Continental Congress and promoting “a spirit of candour, charity, and mutual esteem … towards those of different religious denominations.”[4] Wearing their orthodoxy and loyalty on their sleeves, the Presbyterians demonstrated that they saw no separation of the spiritual and the secular and that they would strive in this time of crisis to build and preserve unions within and for these blended realms.

It would be a mistake, however, to see these union efforts by the Presbyterians in May 1775 as occurring in a vacuum. Seventeen years earlier the Presbyterians had embarked on a mission that made union building a priority for the church. This effort of 1758 was prompted by the schism that had rent the church since 1741. The reunion of 1758 was not intended to be a private affair. The Presbyterians had very publicly split and so they decided to very publicly reunite. In this spirit, they published an account that combined their reunion efforts as well as four promises for the colonial reading world. They first promised to “study the Things that make for Peace;” second, to lead exemplary lives, both in word and deed; third, to ensure that their doctrines were orthodox and evangelical; and fourth, to commend “ourselves to every Man’s Conscience in the Sight of God.” There is no doubt that these efforts were first intended to heal the divisions within the church but this should not obscure the Presbyterians’ intentions towards their fellow colonists in other churches. The synod made this point clearly when it wrote that the ultimate “Design of our Union is the Advancement of the Mediator’s Kingdom.”[5]

Thus, 1758 was the year the Presbyterians formally began an effort to heal the various divisions within the Body of Christ. This was no small undertaking, even if the initial scope was limited to colonial North America. Still, the church did find some success, as can be seen in their coordinated mission work with the Congregationalists among the Native Americans—including the ordination of the first Native American minister, Samson Occom—and their cooperative efforts with the Anglicans in Virginia to create an orderly and peaceful co-existence among the growing number of Protestant churches in the colony. Yet, for all of their notable success in the years that followed, the Presbyterians were still a long way from achieving their goal when British Prime Minister George Grenville introduced the Stamp Act resolutions, which helped spark the American Revolution. As the British Constitutional Crisis developed over the real and perceived challenges to colonial religious and civil liberties, some Presbyterians saw unions with other Christians as an ideal way not only to protect their liberties but also to strengthen the kingdom of Christ. As is evident in the synod’s pastoral letter in the wake of Lexington and Concord, this blending of spiritual and temporal objectives would continue throughout the crisis, all the while altering their original cooperative vision established in 1758.

When Presbyterians throughout the colonies responded to the synod’s four-fold charge in May 1775, most embraced rather than rejected the ruling body’s petition. They joined with their fellow Americans and served as soldiers, chaplains, congressmen, and home support. One example is found in the minister and congregation of Philadelphia’s Third Presbyterian Church, often simply referred to as the “Pine Street” church.[6] Third Presbyterian’s reputation as the “Church of the Patriots” was well earned and a March 1776 worship service led by Rev. George Duffield—future chaplain to the Continental Congress—illustrates this point well. While Duffield supported the synod’s four points in his sermon he also touched on a new idea that was becoming increasingly popular—God had chosen America for a special purpose; it was to be a safe haven for liberty. Duffield reassured his congregation that although through their violent measures the British leadership was actively opposing this plan, God would not be thwarted.[7] “Can it be supposed,” he asked, “that God who made man free … should forbid freedom, already exiled from Asia and Africa, and under sentence of banishment from Europe—that he should FORBID her to erect her banners HERE, and constrain her to abandon the earth?”[8] No, he said, America was to be the new standard-bearer for liberty and would continue as such “until herself shall play the tyrant, forget her destiny, disgrace her freedom, and provoke her God.” Giving their approval of the minister and the message, as one church historian has noted, the congregation let fly with shouts of “To arms! to arms!”[9]

The number of Presbyterians like Duffield borrowing the Puritan’s elect nation ideology increased following the Declaration of Independence. In their various capacities as ministers and laymen, Jacob Green, William McKay Tennent, John Murray, and Abraham Keteltas, to name but a few, drew on the idea.[10] Yes, Great Britain had once been the defender of civil and religious liberty in the world, but they had let that mantle slip. Were Americans worthy, then God would bless them with that honor and “this land of liberty will be glorious on many accounts: Population will abundantly increase, agriculture will be promoted, trade will flourish, religion unrestrained by human laws, will have free course to run and prevail, and America [will] be an asylum for all noble spirits and sons of liberty from all parts of the world.”[11] In this view America had tremendous potential, but as the Presbyterians warned, this glorious future was dependent on Americans humbling themselves through repentance before a holy God. To be sure there were some notable Presbyterian loyalists who resisted the break with the empire, such as William Smith, Jr and William Allen, but on the whole, the Presbyterians were remarkable for rallying around the cause of an independent America that God had set apart for a special purpose.[12]

While the American colonists were not strangers to war, the scope and scale of the Revolutionary War was unprecedented in the history of the British North American colonies. The realities of war’s death and devastation raised difficulties for Presbyterians looking forward to the glorious state they believed God meant for them. The American cause, they still believed, was holy, yes, but something had to be wrong for them to suffer as they had. While many Americans endured devastating losses, a number of Presbyterians believed that the British were singling them out for special punishment as both their institutions and ministers frequently found themselves targeted. For example, following the battle of Long Island at the end of August 1776, the minister of the Presbyterian Church there, Ebenezer Prime, fled for safety. Although Prime escaped capture, his church did not. The British destroyed the minister’s library and they repurposed the sanctuary as a depot and barracks. The redcoats leveled the church cemetery to create a common and the gravestones were used to construct the troops’ ovens.[13] Following the Battle of Princeton in January 1777, Benjamin Rush described to Richard Henry Lee the destruction of one of the most important Presbyterian assets and a bastion of revolutionary sentiment, the College of New Jersey. Rush wrote, “Princeton is indeed a deserted village. You would think it had been desolated with the plague and an earthquake as well as with the calamities of war. The College and church are heaps of ruin. All the inhabitants have been plundered.”[14] A similar fate befell George Duffield’s Pine Street congregation when the British took possession of Philadelphia in September 1777. The church was stripped for firewood and the graveyard excavated and repurposed for dead Hessian soldiers.[15] In August 1779 the New Hampshire Gazette only confirmed what many Presbyterians feared when it noted that the British “manifest peculiar malice against the Presbyterian churches, having, during this month, burnt three in New York State, and two in Connecticut. What, Britons! Because we won’t worship your idol King, will you prevent us from worshipping the ‘King of kings’ Heaven forbid![16]

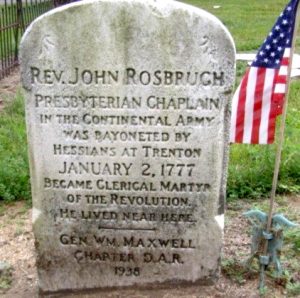

Although the destruction of property incensed the Presbyterians, reports of attacks on Presbyterian ministers and their families upset Presbyterians even more. At the meeting of the 1777 synod, the New Brunswick Presbytery told how “the Rev. Mr. John Rosborough was barbarously murdered by the enemy at Trenton on January second.”[17] According to the story, Rosborough was captured by Hessians while he was looking for his horse. Once it was discovered that he was a Presbyterian minister, he was stabbed repeatedly and left to die.[18] There was also the fate of the “Fighting Parson” James Caldwell, who, as the stories circulating within the Patriot ranks claimed, was also singled out for particular punishment by the British. Accordingly, the British continuously persecuted him through a series of events that ultimately culminated in his death: In January 1780 his church in Elizabethtown, New Jersey was burned; six months later while the Reverend Caldwell was away from home, his wife and children were shot dead while they prayed and his house subsequently burned; in November 1781, a distraught but loyal James Caldwell was assassinated while he was under a flag of truce.[19] While what the Presbyterians suffered, both real and perceived, by hands of the British army only confirmed their need to separate from and resist the empire, they saw something else in their troubles as well. As the minister Jacob Green put it: “Though our contention with Great Britain is so glorious, yet we have reason to be humbled and abased before God … for the many sins, the many vices that prevail among us.”[20]

Despite the efforts of Presbyterians to unite for the preservation of America’s future as the bastion for spiritual and civil liberties, they suffered. Church members persuaded themselves that these hardships, like those of their revolutionary brethren, were the result of unrepented sin. In this spirit, the 1777 synod pleaded with their “congregations, to spend the last Thursday of every month … in fervent prayer to God, that he would be pleased to pour out his Spirit on the inhabitants of our land, and prepare us for deliverance from the chastenings he hath righteously inflicted upon us for our sins.”[21] Repentance and devotion to the law of God were the only safeguards for the proposed nation that the Presbyterians had helped imagine. The synod would repeat the call for repentance throughout the war. There were many sins to choose from—slacking church attendance, discipline and youth education were perennial standbys—but during the war two sins stood out: slavery and the divided Christian Church. Together, the prominent role of these very public sins indicated how the Presbyterian’s new view of America was influencing their faith. Leaders in the church were not prioritizing sins that were confined, in many ways, to individual churches, but rather preference was given to American sins. The Presbyterian embrace of America as God’s chosen land meant they had to engage the national sins that threatened the very potential of the country.

Slavery was seen as a threat not just because it was sinful, but also because it encouraged a great host of sins that crept throughout the land. As the intermittent Presbyterian Benjamin Rush put it, slavery was a “Hydra sin, and includes in it every violation of the precepts of the Law and the Gospel.” These sins corrupted both masters and slaves, and all Americans who came into contact with slavery’s spread. For Rush they were nothing less than “National crimes,” and those, he reminded his readers, “require national punishments.”[22] Echoing these ideas in 1778 Jacob Green told his congregation, “Can it be believed that a people contending for liberty should, at the same time, be promoting and supporting slavery? … I cannot but think, and must declare my sentiments, that the encouraging and supporting of negro slavery is a crying sin in our land.” All Americans needed to repent this sin, Green argued, or they would continue to “groan under the afflicting hand of God, till we reform in this matter.” [23] According to New Jersey chaplain James Francis Armstrong, American slavery was far “worse than Egyptian bondage” and it had left on the hands of the colonists the “tortured blood of the sons and daughters of Adam.” Like many of his fellow Presbyterians, he was not surprised God had visited them with war; rather he was surprised by God’s mercy. “Good heaven!” he cried, “Where sleepeth the lightning and the thunderbolt?” “National calamites,” he concluded alongside Rush, Green and numerous others, could only be remedied by popular repentance and “the exercise of virtue and religion.”[24] The Presbyterians who targeted the institution of slavery saw it in national terms, because if God had set America apart, then that meant the sins it committed as a nation would demand all Americans to repent or suffer divine retribution.[25]

In addition to the sin of slavery, the Presbyterians also turned their attention to the divided Christian Church. From the beginning of the Revolutionary War the Presbyterians had been determined to maintain colonial unity as the synod had implored, by both supporting the Continental Congress and by promoting “a spirit of candour, charity, and mutual esteem . . . towards those of different religious denominations.”[26] Success depended on cooperation, and as is evident, Presbyterians were cooperative. It was an ironic twist then as the war waned, that leaders in the Church, upon re-examining the nature of their unions, found those unions troubling.

The primary problem was that while Presbyterians were working with other Christians on these cooperative ventures, they had become too preoccupied with political liberties at the expense of Christ’s kingdom. What would happen when the main threat to temporal civil and religious liberties was removed? Would the unions among Christians fracture and the old colonial hostilities resume? Samuel Stanhope Smith believed this to be a strong possibility, and in his home of Virginia he foresaw a terrible struggle between Protestants over education. The denomination that “enjoys the preeminence in these will insensibly gain upon the others, and soon acquire the government of the state” he wrote to an equally concerned Thomas Jefferson.[27] “It is time to heal these divisions,” he continued, for “if they were united under one denomination their efforts, instead of being divided and opposed, would concentrate on one object, and concur in advancing the same important enterprise.”[28] Ministers such as John Ewing raised another concern regarding the unions. He pointed out that a “well regulated Zeal for civil Liberty is a noble & generous Passion” and that “endeavours to promote & establish civil and religious Liberty are very commendable.” However, Ewing cautiously added, “amidst all ye vigorous Efforts for Liberty in ye World … how negligent and careless are Men in securing spiritual Liberty.”[29] Spiritual liberty—the most important liberty, the minister commented—was in danger of being supplanted by concerns over civil liberty. The work of Christians, whether individually or in concert across denominational lines, was to primarily emphasize “spiritual Liberty” available through Christ. While the Presbyterians maintained support for the securing of civil and religious freedom, leaders like John Ewing and Samuel Stanhope Smith began calling for a renewed emphasis on strengthening the body of Christ.

Heeding the calls for repentance and renewal within the church, the synod met in May 1783 to address the situation. With peace finally within reach, the ruling body took the opportunity to publicly reclaim their cooperative goals of 1758. Included in this published statement was a formal Presbyterian position on religious freedom, which was intended to dispel rumors that the denomination planned, as the American Anglican Church lay in shambles, to make an Old World power play for a privileged position within the new governments. What many in the Presbyterian Church had begun to fear—that temporal concerns had overwhelmed the eternal goals—was a growing perception outside of the church as well. Their efforts during the war to help shape and lead the American cause were now being portrayed as the first stages of a master plan. Whether the fears were justified did not matter to the synod because the simple fact that they existed indicated a failure of the church. After all, among the promises the Presbyterians made in 1758 were those to “study the Things that make for Peace,” and to commend “ourselves to every Man’s Conscience in the Sight of God.”[30] With their intentions in question, the 1783 synod wrote, “That they ever have, and still do renounce and abhor the principles of intolerance; and … believe that every peaceable member of civil society ought to be protected in the full and free exercise of their religion.”[31] In other words, they hoped to counteract this problem by publicly supporting religious freedom in the new American states.

The synod’s recommitment in 1783 to the goals of 1758 saw the Presbyterians begin their most productive era of Christian cooperation to that point. The Presbyterians began negotiating terms of union with like-minded denominations, such as the Dutch Reformed Church, the Associate Reformed Church, and the New England Congregationalists. This spirit would continue well into the nineteenth century creating many of the voluntary societies that formed the backbone of the Second Great Awakening. But it would be a mistake to see the 1783 recommitment to the cooperative goals of 1758 as just an ecclesiastical affair. The Presbyterian Church had transformed as a result of its experiences during the war. This was perhaps most evident in the way they had embraced the whole of America as their vehicle for uniting and strengthening the “Redeemer’s Kingdom.” Presbyterians had become American nationalists, and while this did not necessarily mean they were wholly or even initially in favor of a strong central government—both adamant Federalist and Anti-Federalist were found within the pews—when the new Constitution was ratified the church’s ruling body fully welcomed and supported the new government.[32] Presbyterians had come to see America’s success as vital to the success of their mission to strengthen the kingdom of Christ. In this way, the Presbyterian Church helped form the vanguard of the nationalist movement while continuing its cooperative efforts with other Christians.

The War for American Independence was a significant turning point for the Presbyterian Church. As the church re-imagined America’s role in God’s plan, they came to wrestle with national sins that threatened that future, specifically slavery and the continued division in Christ’s kingdom. Repenting these sins, they knew, was the only real safeguard for both American independence and the country’s new transformative role in the world. Although slavery would, by the war’s end, take a back seat to spiritual schism, it was not forgotten and would be addressed specifically in 1787. Independence meant that the process of rebuilding lay ahead and the Presbyterian leadership was primarily concerned with uniting Christians for this purpose. However, when the Presbyterians restored Christian unity to its place of priority, it was not as it had been before the war. A nationalist spirit had been joined to their cooperative hopes and it was expected that this interdenominational nationalism would help to transform the newly independent states into an idyllic Christian republic that would benefit and expand the kingdom of Christ. This future, as they told themselves countless times during the war, depended on whether Americans held true to their Christian calling. If they could, as George Duffield told his Pine Street congregation in 1783, America would remain the land where: “God erected a banner of civil and religious liberty: And prepared an asylum for the poor and oppressed from every part of the earth … Here shall the religion of Jesus; not that, falsely so called, which consists in empty modes and forms; and spends its unhallowed zeal in party names and distinctions, and traducting and reviling each other; but the pure and undefiled religion of our blessed Redeemer: here shall it reign in triumph, over all opposition.”[33]

[1] This article is adapted from William Harrison Taylor, Unity in Christ and Country: American Presbyterians in the Revolutionary Era, 1758–1801, Copyright 2017 University of Alabama Press.

[2] John Witherspoon is given credit for penning this letter by Dr. John Rodgers in The works of the Rev. John Witherspoon, D.D. L.L.D. late president of the college, at Princeton New-Jersey. To which is prefixed an account of the author’s life, in a sermon occasioned by his death, by the Rev. Dr. John Rodgers, of New York. In three volumes. (Philadelphia: Woodward, 1800): 3:599–605.

[3] General Assembly, Records of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, 1706–1788 (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1904), 466, 467.

[4] General Assembly, Records of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, 1706–1788, 468.

[5] Synod of New York and Philadelphia, The plan of union between the Synods of New-York and Philadelphia. Agreed upon May 29th, 1758 (Philadelphia: W. Dunlap, 1758), 13.

[6] The Third Presbyterian Church, or Pine Street, still stands today but it goes by the name “Old Pine.”

[7] Quoted in Hughes Oliphant Gibbons, A History of Old Pine Street: Being the record of an hundred and forty years in the life of a Colonial Church (Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Company, 1905), 64.

[8] Gibbons, A History of Old Pine Street, 64-65.

[9] Ibid., 65; Third Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia alone, it is currently estimated, sent six hundred and seventy-two men into battle, with at least thirty-five serving as commissioned officers. This tally is the work of Old Pine Presbyterian’s church historian, Ron Shaffer.

[10] See: Jacob Green, Observations, on the reconciliation of Great-Britain and the colonies. By a friend of American liberty (New York: John Holt, 1776); Abraham Keteltas, God arising and pleading his people’s cause; or The American war in favor of liberty, against the measures and arms of Great Britain, shewn to be the cause of God: in a sermon preached October 5th, 1777 at an evening lecture, in the Presbyterian church in Newbury-Port (Newbury, MA: John Mycall, 1777); John Murray, Nehemiah, or The struggle for liberty never in vain, when managed with virtue and perseverance. A discourse delivered at the Presbyterian Church in Newbury-Port, Nov. 4th, 1779. Being the day appointed by government to be observed as a day of solemn fasting and prayer throughout the state of Massachusetts-Bay. Published in compliance with the request of some hearers (Newbury, MA: John Mycall, 1779); the William McKay Tennent sermon is quoted at length in Joel Tyler Headley, The Forgotten Heroes of Liberty: Chaplains and Clergy of the American Revolution (Birmingham, AL: Solid Ground Christian Books, 2005), 376-380.

[11] Green, Observations, 19.

[12] Perhaps equally telling were Loyalist accounts of the colonial-wide support of the Presbyterians. For instance, Charles Inglis, Anglican loyalist and rector of Trinity Church in New York City, commented to a friend, “I do not know one of them, nor have I been able, after strict inquiry, to hear of any, who did not, by preaching and every effort in their power, promote all the measures of the Congress, however extravagant.” For more see: William Warren Sweet, The Story of Religion in America (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1939), 258-259; and Randall Balmer and John R. Fitzmier, The Presbyterians (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994), 37. On Presbyterian Loyalists see: Joseph S. Tiedemann, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution in the Middle Colonies,” Church History, 74 (2005), 339-343.

[13] Headley, Forgotten Heroes of Liberty, 108-109.

[14] Benjamin Rush to Richard Henry Lee, January 1777, in L. H. Butterfield, ed, Letters of Benjamin Rush, Volume I: 1761-1792, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951), 126. For more on the significance of the College of New Jersey and its president John Witherspoon to the Patriot cause see: Gideon Mailer, John Witherspoon’s American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), especially pages 217-284.

[15] Following the British victory at the Battle of Brandywine, the army occupied Philadelphia from September 26, 1777 to June 18, 1778.

[16] James Smylie, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution: A Documentary Account,” Journal of Presbyterian History 52, no. 4 (Winter 1974): 412.

[17] General Assembly, Records of the Presbyterian Church, 1706-1788, 477.

[18] Headley, Forgotten Heroes of Liberty, 158-162.

[19] Headley, Forgotten Heroes of Liberty, 224-230; Smylie, ed, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution,” 408; Maude Glascow, The Scotch-Irish in Northern Ireland and in the American Colonies (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1936), 274; and J. J. Boudinot, ed, The Life, Public Services, Addresses, and Letters of Elias Boudinot, Volume 1 (Capo Press, New York, 1971), 188.

[20] James Smylie, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution,” 451.

[21] General Assembly, Records of the Presbyterian Church, 1706-1788, 478.

[22] Benjamin Rush, An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, upon Slave-Keeping (Philadelphia: Dunlap, 1773), 30. In many ways Benjamin Rush embodied the spirit of Christian unity discussed here. In 1787 he ended his membership with First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, but he would still regularly attend Presbyterian services. He also frequented Episcopal churches even after his brief formal relationship with that church ended in 1789. For a short while, Rush even attended a Universalist Baptist Church. However, that relationship seems to be largely due to his friend and minister Elhanan Winchester, as Rush never joined the church; after the minister died in 1797 his visits ceased. Even if Rush was formally detached from churches, he maintained cordial relationships with Christians across the denominational spectrum. And Rush had an intimate relationship throughout his life with the Presbyterian Church, as he regularly attended its services and saw all of his children baptized by Presbyterian ministers. See Robert Abzug, Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 11–29; and Donald J. D’Elia, “Benjamin Rush: Philosopher of the American Revolution,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 64, no. 5 (Philadelphia, PA, 1974).

[23] James Smylie, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution,” 451 and 453.

[24] James Francis Armstrong, “Righteousness Exalteth A Nation,” in Light to My Path: Sermons by the Rev. James F. Armstrong Revolutionary Chaplain, ed. Marian B. McLeod (Trenton, NJ: First Presbyterian Church, 1976), 17 and 18.

[25] Other notable Presbyterians, including George Bryan, Elias Boudinot, David Rice, Ebenezer Hazard, William Livingston, John Murray and Daniel Roberdeau, who were influential in both Church and society opposed the “sin” of slavery in addition to men discussed in this article. For more information see Trinterud, The Forming of an American Tradition, 272-74; Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 99–101; Gary B. Nash, Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Viking, 2005), 322–23; and Arthur Zilversmit, First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 128–29.

[26] General Assembly, Records of the Presbyterian Church, 1706-1788, 468.

[27]Samuel Stanhope Smith to Thomas Jefferson, March 1779, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950), 2:247.

[28] Samuel Stanhope Smith to Thomas Jefferson, March 1779 in ibid., 248.

[29] Smylie, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution,” 478.

[30] Synod, The plan of union, 13.

[31] General Assembly, Records of the Presbyterian Church, 1706–1788, 499.

[32] Prominent Federalists included Benjamin Rush, James Wilson, John Witherspoon, Samuel Stanhope Smith, and David Ramsay. Prominent anti-Federalist Presbyterians were George Bryan, Robert Whitehill, and William Findley. For more on religious divisions over the Constitution, see Owen S. Ireland, Religion, Ethnicity, and Politics: Ratifying the Constitution in Pennsylvania (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1995); Stephen A. Marini, “Religion, Politics, and Ratification” in Religion in a Revolutionary Age, 184–217; Miller, The Revolutionary College, 128–38; and Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 255. Marini sees at the heart of this disagreement a persistent Old/New Light contest. Howard Miller contends (and Gordon Wood agrees) that the disagreement was based on the fears of western settlers regarding an eastern centralized aristocracy.

[33] Smylie, “Presbyterians and the American Revolution,” 458–59.

6 Comments

Thanks for a fantastic article!

I am glad you found it useful. Also, thank you for the encouragement.

I really enjoyed your subject matter as it adds significantly to some conversations I recently had regarding Presbyterian history. Thanks for that and, hopefully, to add a bit of regional coverage, I suggest that in the south we know a little something about what happens when the Presbyterians rise up.

Of course they burned the Presbyterian Church. “Sedition Shops”, don’t you know. After all, the old partisan Joseph McJunkin tells us that “A large portion of this district had been settled by Presbyterians and persons of this persuasion were numerous in adjacent parts of North Carolina, particularly in Mecklenburg County. These were generally known as the staunch advocates of independence.”

And so Captain Huck of Tarleton’s British Legion led his dragoons into the “York District, to punish the Presbyterian inhabitants of that place, which he did with a barbarous hand, by killing men, burning churches, & driving off the ministers of the gospel to seek shelter amongst strangers.” Huck later swore that if the rebels were as “numerous as the trees in the forest & if Jesus Christ was to come down & head them, that he could destroy them, which so angered the inhabitants, & God being on their side”, that they hunted Huck down and killed him.

Thanks for the note. I am not sure what sort of market there would be for such a study, but I would like to more thoroughly examine the attacks on Presbyterians and their churches to see whether they were targeted more often. Perhaps one day.

British Major James Wemyss was sent out by Cornwallis into the Pee Dee area of SC to lay waste to whig plantations and homes.. He also burned Presybertian Churchs in the process calling them ” sedition shops”. King George alledged that the war was a “Presbyterian rebellion”..South Carolina Militia General Andrew Pickens was a staunch Presbyterian Elder.

Thanks for the information! You are right that there are certainly stories enough to indicate that Presbyterians were given a higher priority as targets. The trick is to see how closely rhetoric reflects reality. Concerning the complicated use of “Presbyterian” during the period, I would recommend Joseph Moore’s Founding Sins: How a Group of Antislavery Radicals Fought to Put Christ in the Constitution. Thanks again for the feedback!