On June 28, 1777 elements of the 9th Connecticut Regiment that had been fighting with General Washington’s army in New Jersey departed Lincoln Gap in the Watchung Mountains for the return to Morristown and Peekskill. In his journal, Sgt. Simon Giffin of Capt. Caleb Bull’s Company recorded the events of their march[1] “June 28, 1777 marched to Morristown and lodged in tents.” The men were exhausted from the long march deep into New Jersey, long days of maneuvering in cold rain and mud, and tense nights in tents waiting for the battle to envelope them. Now they had another hundred-mile hike to the Hudson. Giffin reported crossing to the east bank of the Hudson River on July 2, and then camping on the plain outside Fort Independence, one of the three forts built near the King’s Ferry river crossing.

The regiment’s commander, Col. Samuel Blachley Webb, noted in his journal that his adjutant, Major Huntington, had arrived at Peekskill with the balance of the new recruits from Wethersfield. The Regiment was temporarily “barracked” in private homes rather than tents because of the miserable weather. Webb noted receiving troubling news from the north that American forces had withdrawn from Fort Ticonderoga without a fight.[2]

Peekskill Friday July 11, 1777 Sir: Major Huntington arrived with the detachment [balance of the regiment] and we barracked them on the inhabitants, the weather being such as was impossible for them to encamp. Confirmation on this day received of our people evacuating Ticonderoga, and that they are retreating towards Fort Edward (on the upper Hudson River).

British forces from Canada had brushed aside the Continentals guarding Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain and were pushing south towards Fort Edward on the Hudson River.

At Peekskill Webb’s Regiment was assigned to General Varnum’s Brigade with the job of guarding the King’s Ferry crossing and the nearby defensive fortifications, Forts Independence, Montgomery, and Clinton. Was the enemy going to attack downriver from the north, or upriver from New York, or both?

Washington began moving his army from Morristown, New Jersey towards the Hudson River. On July 12 they arrived at the Clove, a craggy gorge in the highlands on the west side of the Hudson River. From there they could reach the Hudson quickly, or if necessary turn south and return to the defense of Philadelphia. Two days later Colonel Webb wrote of further confirmation of enemy activities in New York:

July 14, 1777 at Peekskill … By a man just from New York we have information that most of the [enemy] Army have embarked, together with their baggage, artillery, wagons, etc.; he says they are going on some expedition … About 3,500 are to be left to garrison New York and the islands adjacent.

The enemy in New York were loading warships and transports and preparing to depart; but where would they go? Would they sail out into the Atlantic to attack Boston, Philadelphia, or Savannah? Or, would they navigate up the Hudson River towards Albany to join with two British invasion armies moving south from Canada? The situation at Peekskill was perilous. Two British Armies were converging on the Hudson from the north, and a third army was suddenly probing upriver from New York towards the American defenses at Peekskill. Sergeant Giffin wrote in his journal,

July 16, 1777 at Peekskill one ship, a schooner, and two row galleys came up the North River as far as King’s Ferry which occasioned the whole camp to be alarmed and all the troops laid on their arms.

Two days later the enemy flotilla sailed back down the Hudson again, leaving everyone at Peekskill with a bad case of nerves.

Following lengthy preparations, the British armada of some 260 warships and transports carrying some 18,000 troops and supplies sailed into the Atlantic on July 23, 1777. Where were they headed? At Peekskill on the Hudson, the Continental Army watched and waited. Colonel Webb noted in his journal:[3]

Wednesday July 23, 1777 … A number of men are taken down with the measles, this together with the itch makes a number of men unfit for duty.

July 24, 1777 … by a spy from New York we have intelligence the enemy sailed from Sandy Hook yesterday, their destination unknown.

July 25, 1777 this day we intercepted a letter from [British] General Howe [in New York] to General Burgoyne [on the Hudson north of Albany] which says …’we shall sail with the first wind to Boston.’

‘Tis suspected this letter was designed to fall in our hands, so much so that General Washington has ordered some units to cross the [Hudson] river and return to the Jerseys.

July 28, 1777 Orders from General Washington that the whole army at this post is to hold themselves in readiness to march without their baggage on the shortest notice

A week after the British fleet sailed from New York, a flotilla of some seventy vessels from that fleet was seen sailing into the mouth of the Delaware River. Colonel Webb wrote in his journal:

July 30, 1777 General Washington [reported] intelligence that seventy sails of the enemy have arrived in Delaware Bay, in consequence of which the army is moving for Philadelphia.

Washington turned his Army south again, marching it some 150 miles across New Jersey and back towards Philadelphia. Two days later the British squadron turned and sailed out to sea again. What were they doing? Was this some elaborate scheme to draw Washington’s Army down towards Philadelphia while the fleet doubled back to New York and blasted their way up the Hudson to Albany? Or, would they land an invasion force near Philadelphia, seize the capital of the rebellion, and end the war in one masterful stroke?

Despite the continued danger to the Hudson, Washington believed that the enemy’s most likely target was Philadelphia. He pushed his Army south to Wilmington on the Delaware River, a short march from Philadelphia. Again, the enemy kept him waiting. Meanwhile, he again sent out orders to of his generals to urgently send all available reinforcements to him in Philadelphia.

On the Hudson General Putnam was not ready to comply with Washington’s orders as he had already weakened his force by dispatching a Brigade under General Varnum for the twenty-five-mile march into Westchester County. Sergeant Giffin’s regiment was among those assigned to Varnum’s Brigade. Giffin noted, “July 30, 1777 this morning orders came to draw 3 days provisions and all the outposts were ordered to join the regiment.” The departure, however, was delayed by the weather and rumors of an enemy attack. Giffin continued:

July 31 large orders this day, too numerous to mention. Nothing strange.

August 1, 1777 about noon it clouded up and rained and blew as hard as ever it did in the world all night.

August 2- 3 nothing remarkable.

August 4 this day we heard that the King’s ships had come into North River and we expected them up here every moment

August 5 rainy and cold wind from the Northeast.

Fighting spies, Tories, and the weather on the Hudson – August 1777

Webb’s Regiment remained in camp above Peekskill for several more days. On August 8 Giffin noted that the regiment was called into formation to witness an execution. He wrote,

August 8, 1777 This day orders came to be prepared to muster but we was not, and afterwards was ordered to attend the execution of Edmund Palmer that was hanged about 11 o’clock and hung until about sun down and then he was cut down. His friends carried him away on a horse cart. He was a smart looking man and had a family.

In a letter to General Washington, General Putnam described Palmer’s crimes,[4]

July 18, 1777 at Peekskill … Palmer has been lurking around here plundering and driving off cattle to the enemy… breaking up and robbing houses … With a pistol he entered the house of a Mr. Willis… stripped the rings from [Mrs. Willis’s] fingers… and fell upon her aged father, beat him, and left him to all appearances dead … He has been recruiting for the enemy and spying on our Army … A speedy execution … is necessary to the preservation of the Army.

As usual, Sergeant Giffin wrote nothing about Palmer’s guilt or innocence, or any personal feelings about the hanging. This was the business journal of a senior noncommissioned officer, a regimental record and not an ethical or moral essay on the ongoing events of the Revolution. While Giffin was writing about the weather, Colonel Webb was concerned with the successes of the British armies moving south from Canada towards the Hudson River.[5]

Continental Village [Peekskill] Sunday August 10, 1777 … We have intelligence that our Northern Army are retreating, and that the enemy are within twenty miles of Albany.

As yet we hear no further intelligence of the [enemy] fleet and army which was off the Capes of Delaware.

What is clear from Giffin’s journal was that the weather in August 1777 was unusually miserable; during the month a series of cold, wet Nor’easter storms blew down the Hudson River knocking down tents, soaking the men, their campfires, and gear and generally making life difficult for all. He wrote,

August 11 this morning a storm of thunder and rain rose from the North about 4 or 5 o’clock. It burnt one stack of wheat at Crompond and blew almost all our tents down and did a great deal of damage.

Amid this meteorological misery, Giffin noted, “August 13, 1777 … [Private] Adrian Cramer of Captain Bull’s Company was sent to the Hospital.” Company records indicate that Cramer died six days later; the cause of death was not noted.[6] On August 16, another storm lashed the Peekskill area. Giffin wrote:

August 16 hard thunder and lightning struck the mast of a 30-gun ship that lay in the river belonging to the states.

August 17 this day Benjamin McInbur was tied up to a tree naked but not whipped … for losing his cartridges.

August 18 this day drew 917 cartridges for the use of the Regiment.

August 19 this day marched to North Castle and lodged there.

August 20 this day marched to White Plains and from there to Landon Woods place General Howe’s Headquarters last year and lodged in a barn.

The following day they continued their march, but this time a clash with the enemy occurred:

August 21, 1777 marched to East Chester and sent out some scouts which brought in 9 of the enemy prisoners and 2 commissioned officers … [We] had a smart fire [a firefight] a little while but not many were killed or wounded. Benjamin McInbur was wounded in the foot. We marched from Eastchester leaving 1 captain, 1 corporal, and 1 private missing. They had not got in [and] I am afraid they are prisoners.

Capt. Judah Alden and Pvt. David Chapin of Webb’s Regiment died during the fighting.[7] The next day the Brigade withdrew some eleven miles north to King’s Street (today’s Armonk, New York) where they set up camp and Sergeant Giffin distributed provisions.

August 23 was quiet and Giffin wrote “nothing happened this day.” Then, something happened; he promptly crossed out his brief note and replaced it:

August 23, 1777 … Nothing happened his day About nine or ten o’clock we were alarmed this evening by sum guns that were fired at sum Tories that came to steal horses, but they got off with 3 or 4 horses before they were stopped by us …[That night we] lay in a fort that was built by our people last year after the retreat from White Plains called Fort Nonsense.

Their march north continued uneventfully for the next two days passing through North Castle, Crompond and back into their previous camp at Number 2 Barracks outside Peekskill. It was good to be back in substantial wooden barracks again, as Giffin noted, “August 26 rained all day and a cold wind blew in from the north.” Except for those on guard duties, the men would spend the next four days inside, sheltered from the storm.

Finally, the weather cleared, and General Putnam put his men to work on training exercises. Giffin wrote,

August 30, 1777… this day all the Brigade drew twelve rounds of cartridges without balls and marched down to the Grand Parade with the artillery and then had a sham fight with field pieces and light horse.

For the first time in Sergeant Giffin’s record, General Putnam was practicing battlefield tactics involving all his infantry, artillery, and light horse (cavalry). Practicing standardized movements was essential to success on an eighteenth century battlefield where the inevitable confusion, noise, and chaos made it extremely difficult to properly position and maneuver units in response to developments.[8] Putnam was training his men to think, and to move together, and to fire their weapons in a controlled and coordinated manner. Later that week the exercises continued:

September 4 this day had a sham fight the whole brigade divided into two parts. General Varnum headed one party and Col. Livingston the other party. Nothing strange [happened].

Throughout this time, Giffin’s notes reveal that Putnam’s army at Peekskill was experiencing serious disciplinary problems. On September 5, Giffin noted that Pvt. John Burns of Captain Hart’s Company was tried and convicted for disobeying an officer and threatening to kill a man. He was sentenced to a minimal punishment of fifteen lashes. Under normal circumstances disobeying an officer might result in one hundred lashes or a firing squad. There must have been extenuating circumstances; but Giffin chose not to record them.

The next day Sergeant Giffin witnessed several more punishments. Three unnamed men from General Varnum’s Brigade were marched up gallows hill to be hung. One man was left on display with the noose around his neck for thirty minutes and then whipped fifty lashes; two others were similarly displayed and then given a whipping of one hundred lashes each. Again, Giffin did not describe their offenses, although they must have been serious as the three men were then sent off to prison ships for the remainder of the war.

On September 9, 1777 the regiment was assembled to witness more corporal punishments Pvt. Amos Rose had been convicted by a court martial for firing his musket at Ens. Elisha Brewster.[9] Also, Lemuel Ackerly, a “Tory from Westchester County,” was convicted of robbery and spying for the enemy. Giffin reported that the two men were marched up gallows hill to be shot. However, at the last moment their death sentences were reduced to confinement on a prison ship for the remainder of the war.

It was the 12th of September 1777 before Giffin recorded any good news: “this day orders came for us to join General Parsons Brigade, which was good news for us, and to march immediately.” The “good news” for Sergeant Giffin was the order to move again. The inactivity at Peekskill had resulted in too many disciplinary problems. Almost any sergeant in any army would agree that inactivity and boredom are the principal causes of problems in the ranks; and the best way to reduce such problems is to keep everyone busy.

General Parson’s Brigade, which included Webb’s Regiment, was ordered to return deep into Westchester to again monitor enemy activities and to find and eliminate a particularly active band of Tory militia called “Delancey’s Cowboys.”[10] Col. James Delancey came from a well-known New York Loyalist family. During the war he remained loyal to the crown, forming the Westchester County Militia and enlisting prominent citizens of the region including New York island (Manhattan) and Connecticut. These Loyalist citizen-soldiers patrolled the no-man’s land between British and American lines that encompassed much of Westchester County. They earned their nickname from their penchant for stealing cattle and horses.

Parsons’ Brigade had lost men and horses to raiders on their previous visit to Westchester County and the General was determined to seek revenge. Now, on September 13 the brigade departed Peekskill again, marching some eighteen miles south to North Castle. Sergeant Giffin reported sleeping in a barn that night, and upon awakening the next day he noted:

September 14, 1777 … there was a white frost on the ground this morning … we marched from North Castle to King’s Street and lodged there.

September 15, 1777… saw a large number of enemy ships a going up [Long Island] Sound, about thirty or forty in number

Were these warships or transports moving troops? It would be several days before he would know.

Parsons’ Brigade arrived at White Plains in the afternoon of the 16th where Giffin issued rations, a pound of uncooked beef and a pound of flour for each man, advising them to cook everything immediately and be ready to depart at a moment’s notice. But again, a storm of cold wind and rain swept through the area; and the regiment remained in place for several days (September 16-19). Throughout this time the men were huddled about under dripping shelters, stoking smoldering fires with wet wood while some two dozen men were rotated out into the storm as pickets around the camp to prevent surprise attacks by the enemy. Inevitably, more and more men were sent off to the hospital to recover from colds, flu, stomach cramps, and dysentery.

At this time while his regiment was camped at White Plains, Colonel Webb was ordered to take a raiding party out to Long Island. From a camp at New Windsor, New York, he would later write in his journal,[11]

October 8, 1777. On the 16th of September 1777 I marched from Peekskill at the head of 500 men; three nights following we made a descent from Fairfield on to Long Island, arrived at the fort in Setauket about day break. The enemy had previous notice of our coming and were prepared to receive us. Our design was a surprise, [we were] disappointed in this. We fired on the fort near three hours, and then by a council called by General Parsons concluded to retire, the enemy shipping then drawing near to destroy our boats. We landed safe on the main without the loss of a man … after laying 3 days at Fairfield we marched for Norwalk and from there to Horseneck where we continued for about a week.

Meanwhile, Sergeant Giffin reported from White Plains that it was windy and cold all week (September 14-20) and the men were ordered to prepare to depart on short notice. Finally, the weather cleared and Giffin reported, “September 21, 1777 Sabbath a fine, pleasant day. Orders came to wash all the blankets … and to keep out large scouts all the time.” That Monday Sergeant Giffin reported encountering the enemy at the Stone Church in Eastchester (today’s St. Paul’s in Mt. Vernon, New York). He wrote:

September 22, 1777 this day I went out in a scout of 400 men commanded by Col. Charles Webb marched about a mile below the stone church at East Chester and discovered 12 Light Horse belonging to the King’s Troops, but they saw us and made their escape. Returned home to our encampment the same night.

The grey stone and brick church at Eastchester was Anglican Catholic. [12] Being Church of England, the congregation was largely Tory, and the Church building stood empty most days. Throughout the Revolution this heavy stone bastion was repeatedly fortified, fought over, and used as an assembly point, refuge and hospital by both sides; and Webb’s regiment would make several return trips to the church. Being Presbyterian, Sergeant Giffin would frequently refer to it as the “Meeting House,” rather than a church.

On September 23, 1777 Giffin noted, “the band of musicians came in this day.” This was Colonel Webb’s regimental band, organized and equipped by Webb and other officers of the regiment. The regimental rolls for 1777–1780 list some sixteen men as being “musicians,” among them Drum Major Thomas Quigley, and Fife Majors William Patterson and John Kirkuk.[13] According to one authoritative source, by 1777 band members were expected to carry weapons and their combat functions were to be considered more important than their musical skills.[14] The band that accompanied the regiment was presumably carrying muskets as well as musical instruments as Westchester County was full of Tory Cowboys and the British Army encampments along the Bronx River were not far away. On September 25 Giffin reported,

September 25, 1777 this day cannon were heard all day towards New York. We had 2 men come in that deserted from the enemy this day that informed us that there was 5,000 men landed at New York who had word that they was coming out upon us this night. But it rained very hard that prevented it. Lay on our arms all night to be ready for them. sent all our baggage away to Kings Street.

The regiment remained in place on the 26th and then departed late the next afternoon “with colors [flags] flying and the band of musicians playing.” At King’s Street the men “lodged in good houses”; Sergeant Giffin “kept the lower guard with 20 men.” Another witness to that cold September day was a Connecticut teamster named Joseph Joslin. He wrote in his journal,[15] “September 27 at White Plains clear and cold, frost as thick as window glass … I unloaded markee [marquee] clothing for the band of Col. Samuel B. Webb’s Regiment.”

On September 28 the regiment turned north again, marching to the lower end of North Castle (Armonk, New York) where Giffin distributed rations (fish, bread, and beef) and they spent the night. The next morning, they returned to Peekskill where they camped on the hill above General Putnam’s headquarters. Back at Peekskill, the men lay quietly for several days (September 30 – October 3, 1777).

Meanwhile the generals were busy writing letters. General Putnam and New York Governor George Clinton were both frantically writing General Washington and John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress, pleading for urgent reinforcements on the Hudson. Putnam was convinced that an enemy assault force of 5,000 men was preparing to ascend the Hudson River, shatter his undermanned fortresses at Peekskill, and proceed upriver to Albany. Putnam and Clinton emphasized that they “did not want to be held responsible for the impending disaster”.[16]

Washington, meanwhile, was struggling with a vastly more powerful enemy pushing from the Chesapeake towards Philadelphia. He again ordered that all available reinforcements on the Hudson to be urgently dispatched to him. Putnam reluctantly sent off half of his force, leaving him with only 1,000 Continentals at Peekskill; and, he resumed his letter-writing campaign.

On October 2, Putnam again warned Hancock and Washington that an enemy assault up the Hudson was imminent. He did not have sufficient forces to counter such an attack; and he refused be held responsible for the inevitable disaster. Washington must have been furious with a subordinate who continued to ignore his orders and to send reports “over his head” to the President of the Congress. Unfortunately, there was little Washington could do to control Putnam as the man was wildly popular in New England and among a great many representatives in Congress. A commander less patient than George Washington might have precipitated a crisis by removing his critic, but Washington wisely did nothing, as both men were soon occupied with more pressing matters.

Fighting for the Peekskill forts

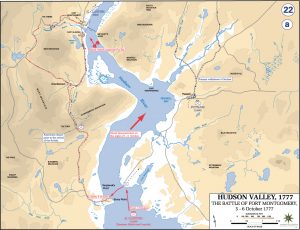

On the same day as the Battle at Germantown, October 4, 1777, a powerful enemy flotilla surged up the Hudson River from New York towards King’s Ferry. Sergeant Giffin reported in his journal.

October 4, 1777 this morning news came that the enemy was a coming up the North River. The alarm gun was fired. They came up and landed at Kings Ferry.

October 5 marched up to No. 2 barracks and took possession of the hill. Lay on our arms all night.

October 6 Monday this day the enemy came up on the back of Fort Montgomery and attacked it. Our people were obliged to leave the fort by reason of the enemy being too numerous for them and forced the lines. Our regiment went to re-enforce them but as we came to the river they got possession of the fort so we had to return to our camp.

October 7 this day marched to Fishkill and lodged there

General Putnam sent a more complete description of the events in his report to John Hancock of October 6, 1777.[17]

October 6, 1777 at Peekskill.

Sir … On the morning of the 4th the enemy came up this river … a fleet of between thirty and forty flat-bottom boats, in convoy with of some ships of war, some galley’s and tenders … foggy weather prevented them from being discovered until they reached Tarrytown, about 20 miles below Peekskill.

they landed about 2,000 men and marched about 5 miles into the countryside. Finding that our people had driven off the cattle and harassed by militia … the enemy again boarded their fleet and moved upriver to Kings Ferry, where they immediately took possession of Fort Independence without opposition

The militia garrison was too small to resist a large invasion force supported by powerful naval cannons … I have less than 1,000 Continental Troops … I cannot warrant that I will be able to prevent them from taking the Peekskill forts… neither do I feel myself answerable for it

After destroying Fort Independence on the east bank of the Hudson, British Gen. Henry Clinton waited a day and then on the morning of October 6, obscured by a dense fog, he shifted his army over the river to Stony Point on the west bank. Marching his men inland around the back side of Bear Mountain, he scattered a small guard post of some thirty Americans at Doodle town, and then descended upon the backsides of Forts Clinton and Montgomery. As the British expected, the American cannons were mostly facing the river, giving the attackers a distinct advantage in the battle that ensued. The forts fell, with losses on both sides, leaving the path up the Hudson open to British forces.

How far upriver would the British push? General Putnam ordered his remaining forces to move north up the Hudson towards the next major river crossing. On the day following the fight below Peekskill, Sergeant Giffin wrote, “October 7, 1777 this day we marched to Fishkill and lodged there.” As was his usual custom our diarist spent no ink reflecting on the loss of the three forts above the King’s Ferry crossing, the wounded and dead, or the miseries of those taken prisoner during the fight. For Sergeant Giffin the war continued without critical analysis; his Regiment had orders to move up the Hudson to the next crossing and to blunt further British advances.

[1] Simon Giffin, The Diary of Quartermaster Sergeant Simon Giffin of Col. Samuel B. Webb’s Regiment 1777-1779. See Also: Record Book of Quartermaster Sergeant Simon Giffin 1779-1783. Photocopies and microfilm of the originals are at the Connecticut State Library and Archives in Hartford. Special thanks to cousin Robert E. Mosier, jr. for providing the author with an original photocopy for transcription.

[2] Samuel B. Webb, Correspondence and Journals of Samuel Blachley Webb, Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed. (Wickersham, NY: Wickersham, 1893). Webb. Correspondence, 1: 219, 220.

[3] Ibid., 1: 222-24.

[4] Ibid., 1: 247, 254.

[5] Ibid., 1: 227.

[6] Henry P. Johnston, The Record of Connecticut men in the Military and Naval service during the War of the American Revolution 1775-1783. (Hartford: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Co., 1889), 218.

[7] Johnston, Connecticut men, 246, 248.

[8] Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1983), 5, 113, 119.

[9] Webb, Correspondence, 1: 250, 259, 288.

[10] R. M. Hatch, Major John Andre: a gallant in spy’s clothing (Boston: Mifflin, 1986) 1-2, 110.

[11] Webb, Correspondence, 1: 229-230.

[12] National Park Service, “Historic St. Paul’s Anglican Church Eastchester, NY,” www.nps.gov/sapa/historyculture/st-pauls-church-history.htm

[13] Johnston, Connecticut men, 247.

[14] Wright, Continental Army, 38.

[15] Joseph Joslin, “The Journal of Joseph Joslin 1775-1778,” in Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society Vol. VII (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1899), 327 – 28.

[16] Webb, Correspondence, 1: 319, 328, 331.

[17] Ibid., 1: 322-24.

5 Comments

Although Sgt. Giffin’s journal entries are matter-of-fact and unadorned, their cumulative effect is highly impressive. Indeed, the series of articles on which they are based illustrate a crucial factor in the eventual victory of his side in the war. Through his day-to-day account of the struggle, we see that he not only endured but also continued to carry out the essential duties of an NCO in maintaining a disciplined army in the field. It was the determination and ability of NCOs like Giffin to persist that doomed the British to ultimate failure.

Dear Dr. Kernek: Thank you for your comments, high praise from a Cambridge man. I try not to be unfair to the British while being thoroughly impressed with the commitment of the ordinary American soldier (then and now), and particularly the senior NCOs. We were such rank amateurs in 1775-76. Only perseverance, adaptability, and a lot of help from the French allowed us to fight on. Thanks again for high tea in the English countryside. Phil

Phillip: Your progressive, almost novelistic narrative of our dear Sergeant Giffin, continues to elucidate more historical and personal matters. I feel like I’m getting closer and closer to his “character” as the “story” of his “revolutionary” activities advances. Although we don’t have verbose, philosophical statements from him regarding the “cause” he is fighting for, we are rewarded with details of his grit and determination and actions as a good soldier and provider, and they speak so much to the value of him as a person of belief in doing the right things for the sake and health of the colonies. And for his men.

More and more, your wonderful contextual commentary adds so much to the narrative, as to make your overall history of Giffin’s movements very colorful and engaging. Once again, I must repeat to you and your audience my feelings about your overall contributions to this Journal which I stated about your January 11 piece: “The fruits of your sacrifice, Phil, are giving historical novices like me, and other more serious historians, a lot to consider as the microhistory of our intrepid Sgt. Giffin grows and infiltrates our consciousness– about the Revolutionary activities of the common man in the 1770’s and 80’s in the Continental Army. ”

Mr. Giffin, I commend you for this latest installment, and look forward to the continuing history of Sgt. Giffin. Keep up the good work. Your audience, I’m sure, is growing!

Leonard: Thank you for your kind comments. I believe it was you who introduced me to the idea of micro vs. macro history… I love the personal stories that make the macro (overall) picture so much more interesting. Sgt. Giffin was a taciturn fellow but his daily journal provides a real feel for the privations, difficulties, & dangers of the war and the commitment, perseverance, and hard work to accomplish the job. Your comments are appreciated. Phil

Hi Phil,

I enjoyed reading each of your features, including on Sgt. Simon Giffin, your ancestor. Small world: Like you, I am also a regular JAR contributor (see my JAR page for my five features), and I live here in Wethersfield, only a half-mile from Giffin’s grave, but I also own the General Huntington House in Norwich. I’d love to know if your ancestor kept recording after October of 1777. Did he serve the typical three years through 1780? Did he serve at the Battle of Monmouth? Thank you and look forward to hearing from you, Damien