After the fall of New York in 1776 Long Island became occupied territory for combined British and Loyalist forces during the remaining years of the Revolutionary War. The island became an important supply resource for the British army in New York City and a defensive front line to the American forces in New England. The New York region including Long Island endured the longest continuous British occupation period of the entire war. Long Island became a much needed territory for wintering and quartering troops. Although activities at the headquarters in New York City are well recorded in orderly books, correspondence and other manuscripts, the activities of troops and their housing situations on Long Island are not well documented. One of the better-known units stationed on the island in 1778-79 was the famed British Legion.

The British Legion was a combined Provincial cavalry and infantry unit that was commissioned by Lord Cathcart in 1778. Shortly after its organization its leadership passed to Col. Banastre Tarleton who commanded the cavalry and Maj. Charles Cochrane who commanded the infantry. The Legion early in the war had four infantry companies and three cavalry troops with a combined strength of 333 men.[1] During the winter season of 1778-79 the Legion’s activities on Long Island give insight into the unit’s characteristics early in the war and its initiatives for supply requisition. The records also hint at the types of discipline issues that occurred among British and Loyalist troops in winter quarters.

After the capture of New York City in 1776 the British army needed adequate housing for its troops. Naturally, this need coincided with the best opportunities for supply and Long Island provided ample resources for this requirement. Sir William Howe early in the war received a letter from a local informant that summed up the advantages of the Long Island area to him in his considerations for troop housing.

it is 130 miles long, it is very fertile, abounding in wheat and every other kind of corn, innumerable black cattle, sheep, hogs, &c. is very populous, and Suffolk county in particular, as well as the other parts of it all good and loyal subjects, of which they have lately given proof, and only wait to be affiliated by the King’s troops. The island has a plain on it at least 24 miles long which has a fertile country about it[2]

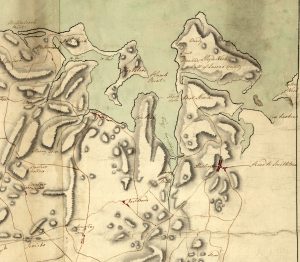

The plain noted was the Hempstead Plain and the fertile country mentioned would have been its adjacent areas within western Long Island. The 17th Regiment of Light Dragoons was quartered in Hempstead and the British Legion in Jericho in the township of Oyster Bay.[3] Jericho was an ancient Quaker community established at the crossroads of several early roadways. The roads through the village allowed access to the village of Hempstead to the south and to Jamaica and New York City in the west. The crossroads also allowed passage to points further east out on Long Island. The plain afforded ample room for pasturing cavalry horses, and important consideration in keeping them fit for the summer campaign season. Seth Norton, a forage master for the British Army, recorded orders for the establishment of a post at Jericho in 1778.[4] Among Norton’s papers is a note written by Banastre Tarleton dated November 11, 1778 from Jericho, stating, “I am to request that you furnish the Bearer with a Barrel of Oatmeal for the Foxhounds.”[5] This note confirms that Tarleton’s concerns in the Jericho area included more than just military essentials.

At roughly the same time several high ranking officers of the British army present at Jericho. Correspondence to General Washington from an informant working for the American cause on Long Island states that Brig. Gen. William Erskine, who commanded the British troops on eastern Long Island, was at Jericho and was building “works” around Doctor Townsend’s house where he himself was quartered.[6] A report from General Parsons in Connecticut records that there were 700 troops stationed in Jericho at this time in 1778.[7] In December of that year Norton wrote, “Col. Simcoe is to be at Jericho and you must be getting a magazine for him,”[8] and that hay and oats were needed there. Apparently Simcoe’s regiment, the Queen’s Rangers, were also housed at the post.

Correspondence to Seth Norton confirms that the British Legion constructed the post at Jericho. A newspaper says that the British troops were building barracks or huts there.[9] Henry Onderdonk, a nineteenth century historian, added a footnote about the British Legion in Jericho in his Revolutionary War writings: “The Legion built a fort called Fort Nonsense on a hill around Dr. Townsend’s barn.”[10] Taken together, these records indicate that the Legion set up an encampment and defensive work here for their infantry and cavalry components. The property was historically that of Dr. James Townsend who had moved his medicine practice to the Jericho homestead in 1757. The speculation is that the property may have been selected for British army use as a form of punishment because Townsend had been a member of the provincial congress prior to the enemy occupation of the island.[11]

Accounts of a raid at Smithtown on November 21 to 24 give details about the Legion’s activities in Suffolk County. Colonel Tarleton and Major Cochrane were present at the Inn of Epinetus Smith on November 21, 1778 and acquired a significant bill of services and acquisitions from the innkeeper. A major collection of supplies was made ranging from animals to building materials, liquor and silk fineries. Colonel Tarleton himself seems to have acquired his own gracious helping of these, including four sheets and one new Petticoat and one silk handkerchief.[12] A November 12, 1778 inventory of hay at Jericho reports that one ton of hay was confiscated from James Townsend’s in Jericho and fifteen tons were also acquired from Benjamin Townsend’s property in the same area.[13]

An account book kept by the Society of Smithtown includes a claim by the Society for 127 pounds 18 shillings 4 pence for 6396 feet of boards at 20 pounds 8 shillings per thousand taken from out of the Presbyterian Church in November 1778. The notation says that, “The above boards were of the best pine and taken for the use of the Government by Colonel Tarleton and Major Cochran.”[14] So where was all this material going? Were these the supplies used to build the winter encampment at Jericho? It is unclear if this large acquisition of material was for the Legion’s use or if it was acquired for shipment to New York.

Seth Norton made frequent complaints about the Legion’s conduct. He stated, “if the Quartermaster’s of the Legion are not restrained by the particular Order from Headquarters (for they will pay no attention to any Commissary’s Order) from taking the Forage, engaged for this Magazine I shall not be able to get even a sufficiency for this Corps.” He elaborated on the Legion’s mischief: “two or three days ago they were at Wolver Hollow about four miles from this, taking all kinds of Forage without granting receipts, the Inhabitants make frequent complaints and Col. Simcoe has once sent out a Party with Mr. Dix & drove them off.” He continued, “they returned the next day and they have at Jericho, including the Plain Hay more Forage than the number of horses now they ought to consume this season.”[15]

Little is know of the location of the British Legion’s post at Jericho. The position known as Fort Nonsense was one of many Revolutionary War forts of a similar name, including several American works in Connecticut and New Jersey. The term was used in these instances to denote positions of apparent folly in their establishment. There is a chance that Fort Nonsense at Jericho was a product of a similar misjudgment. John Graves Simcoe recorded in his journal that

Sir William Erskine came to Oyster Bay, intentionally to remove the corps to Jericho, a quarter of the Legion was to quit in order to accompany him to the east end of the island. Lt. Col. Simcoe represented to him, that in case of the enemy’s passing the sound, both Oyster bay and Jericho were at too great a distance from any post to expect succor, but that the latter was equally liable to surprize as Oyster bay , that its being farther from the coast was no advantage, as the enemy acquainted with the country, and in league with the disaffected inhabitants of it, could have full full time to penetrate, undiscovered , through the woods.”

He continued, “Sir William Erskine was pleased to agree with Lt. Col. Simcoe; and expressed himself highly satisfied with the means had been taken to ensure the post.”[16] The fort at Jericho may have been known as mere nonsense within the ranks and as such its existence could have been passed down as a fictitious reality. The truth of the fort’s existence is yet to be uncovered.

The extent of British Legion’s post at Jericho is still unknown but what is certain is that the force was present and active in that area of Long Island during the winters of 1778-1779. As a new unit ripe with passion for their duty they were wholeheartedly enthralled with the needs of their command and anxious to exhibit their effectiveness in the British cause.

[1] “State of particular Companies of the Provincial Corps for a General Muster &ca Feby. 1779,” Dreer Collection, Misc. Mss No. 11, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[2] The North British Intelligencer or Constitutional Miscellany, Volume I (Edinburgh, 1776), 221.

[3] Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1957), 229, 319.

[4] Seth Norton, 1775, Revolutionary War papers, Hofstra University’s Long Island Studies Institute, Nassau County Museum Reference Collection.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Charles Scott to George Washington, November 10, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives.

[7] Lewis J. Costigin to Washington, December 13, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives.

[8] Seth Norton incoming correspondence, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford.

[9] The New-York Journal and the General Advertiser (Poughkeepsie, NY), December 2, 1778.

[10] Henry Jr. Onderdonk, Documents and Letters Intended to Illustrate the Revolutionary Incidents of Queens County: With Connecting Narratives, Explanatory Notes, and Additions (New York: Leavitt, Trow and Company, 1846), 209-210.

[11] Richard A. Winsche, “The Jericho Historic Preserve,” The Nassau County Historical Society Journal, Volume 39, 1984.

[12] Blydenburgh manuscript: inhabitants of Smithtown v. King George III, transcribed from the original document residing at the Smithtown Historical Society, Smithtown, NY, 1783.

[13] Norton collection of papers of Reuben Smith Norton and Seth Norton, Connecticut State Library.

[14] Blydenburgh manuscript.

[15] Seth Norton,1775, Revolutionary War papers.

[16] John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s military journal: a history of the operations of a partisan corps, called the Queen’s Rangers, commanded by Lieut. Col. J.G. Simcoe, during the war of the American Revolution (New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844), 94.

One thought on “Oatmeal for the Foxhounds: Tarleton in Jericho”

Nicely done, Mr. Griffin!