Sgt. Benjamin Gilbert of the 5th Massachusetts Regiment awoke near Verplanck Point on May 31, 1779 with cause to celebrate: it was his birthday, and he was now “four and Twenty Years of Age.” He didn’t celebrate too long, for British “Shipping appeard in sight this Morning and came & [played] upon” Fort Lafayette, the primary Continental defensive work on Verplanck Point. It was clear that the British were in force – not only was their shipping swarming the area between Verplanck and the rocky peninsula across the Hudson River, Stony Point, but Major General Vaughan was leading a few thousand redcoats to Verplanck by land. Outnumbered, the Continentals “Marched to the [Continental] Village and staid all Night,” leaving a detachment of North Carolinians under Capt. Thomas Armstrong at Fort Lafayette to hold out for another day.

By late in the day on June 1, the Crown forces had full possession of Stony and Verplanck Points, and the vital crossing they comprised, King’s Ferry. Little did Benjamin Gilbert, the now twenty-four year old soldier, know that he had witnessed the catalyst that would put King’s Ferry and the entrance to the Hudson Highlands into a flurry of activity that would last nearly five months, activity to which he himself would be called to respond.[1]

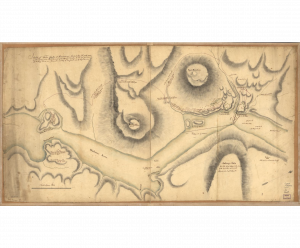

The events that followed, namely the storming of Stony Point on July 16, 1779, the attempt on Verplanck (unsuccessful), and months more of Crown possession of King’s Ferry are well known. What is less known are the number of incidents in which both American and British forces tested each other’s will to maintain (or break) the overall stalemate in the third quarter of 1779 through the use of one particular medium: guard boats. When the British occupied the ferry, they had been accompanied by Royal Navy vessels: HMS Vulture, HMS Rainbow, and others, and moderately-armed row galleys such as the Philadelphia and Cornwallis. There were also many nameless guard boats, on both sides, that engaged with each other or with land troops within a range of four miles of King’s Ferry.

Guard boat activities began as early as the last week of June. Maj. Gen. William Heath ordered Col. Rufus Putnam, an officer skilled in reconnaissance and engineering, to scope out British positions at King’s Ferry. On June 30 Putnam reconnoitered the “Enemy, with due pre caution … [taking his own] Light Company, as a Guard … and proceed[ed] Down the river in Boats [for] the best view can be had from the Dunder berg you will land at or near Fort Montgomery.” To ensure the cooperation of any Americans in the area, Heath mentioned the mission in orders, stating that not only was Putnam proceeding “down the River as far as may be thought Convenient in Boats,” but that “any of the Light Troops of the Right wing [who] should be posted at or near the Dunderberg the Commanding Officer is desired to afford Colo. Putnam any Assistance he may need.” The Light Troops being referred to were in Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne’s Corps of Light Infantry, whose encampment stretched from the ruins of Fort Montgomery northerly to Sandy Beach.[2]

Heath, an active officer, wanted more information on the British situation below him (he was near today’s Garrison, New York, opposite West Point), and he grew impatient for the latest news. To acquire this, he needed boats; Heath pressed Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall (commanding at West Point) for them but was denied. Heath wrote to Washington on July 10 for answers: “ I wish to obtain the earliest notice of the movements of the Enemy … to facilitate this I would request that Two of the four Guard Boats, at present employed, and which are manned by Crews from the Division I have the honor to Command [that is, New Englanders], may be kept … under my direction.” Barring the Commander-in-Chief’s disapproval, Heath requested that McDougall’s boats at least report to him or, failing that, that Washington not be opposed to Heath’s procuring his own boats. A compromise was made; three days later on July 13, Captain Buchanan, in charge of West Point’s boats, wrote to Heath saying that “after so long time I have sent your honor a boat.”[3]

The following day, July 14, found a boat crewed by members of the 5th Massachusetts Regiment (in which Benjamin Gilbert served) heading past Fort Montgomery. They had not quite gotten into Peekskill Bay before their luck ran out; British vessels had caught up to them. One of the man, Pvt. Seth Kellogg, recalled that the crew was “taken prisoner … while on board of a guard boat in the North [Hudson] River … by a party of British from on Board the British fleet that then lay at Kings Ferry.” Kellogg and five others were taken aboard HMS Vulture. Days later, they were transferred to HMS Raisonable, en route to New York and Wallabout Bay, where until September 1779 Kellogg at least, would be confined to the Good-Hope hulk.[4]

The next day, July 15, grew windier and windier, as some of the King’s Ferry vessels, like the Vulture and her associated gunboat, dropped down to the top of Haverstraw Bay to have more room to ride out the weather. This proved an unfortunate move for the Crown, as hours later, Wayne’s Light Infantry captured Stony Point; the captured guns were put to use against Verplanck and the shipping. The combination of the weather and surprise of the attack (the Vulture had severed one of her cables) gave no chance for the vessels to successfully contest Wayne’s victory. By evening on July 19, the Corps of Light Infantry had returned to their former location at Fort Montgomery, the British under General Sterling (not to be confused with the American General Lord Stirling) had repossessed Stony Point; and King’s Ferry was still in British hands.[5] Earlier that day, Washington had issued the army’s General Orders and gave special instructions for boat use: “The Light Infantry are to take post at any convenient place near Fort Montgomery … The Guard-Boats are to be under the direction of the officer commanding the Light Infantry from which corps they are to be manned.” After the minor debate between Generals McDougall and Heath regarding who would look after the guard boats, General Wayne won out. Washington’s decision made military sense: Light Infantry were to act as a screen for the main army (at the time encamped in a large arc centered on West Point), and their forward position at Fort Montgomery, right on the Hudson and a mere six miles from British positions, necessitated Wayne probing the enemy and providing a first line of defense for the Highlands.

A return from July 1779 gives us a hint as to exactly what boats the Light Infantry were in charge of: three whaleboats and three bateaux. A whaleboat is a long boat, “sharp at both ends, and steered with a rudder or an oar, used in” whaling; typically rowed. A bateaux was generally “flat-bottomed, double ended” and rowed, but could have a single sail, should the weather prove it useful.[6] Washington reaffirmed his intentions (to Wayne) regarding the boats: “The look out boats I have desired Genl McDougal to order down to be under yr command that you may officer & man them, with such persons as you can confide in – this will enable you to obtain the earliest notice of the enemys movements, & should any take place, or any thing important occur – you will take care to have it communicated … in the vicinity of West Point.”[7]

Within a few days of Washington’s letter, the British boats would become bold, not towards their American counterparts just yet, but against the largest target in the area: Peekskill. Another compatriot of Benjamin Gilbert’s, Pvt. Zebulon Vaughan, noted in his diary that on July 26, in the “for noon th[e] Brigad was [alarmed] by Some bots that Come ae Shore att pickills [Peekskill] but Soon returned Bord the galey.” Though a flash in the pan, the galley Vaughan mentioned would become resident in Peekskill Bay for the next few months, and prove to be a thorn in the American side. A sailor (unnamed) from the HMS Raisonable who had fallen into American hands (unclear as to how) reported that a galley, probably the same mentioned by Vaughan, was “stationed at Piggs-kill to protect a bridge over a morass,” and that it was “relieved every week.”[8] The next two weeks were mostly quiet on the water. The Light Infantry continued to scout and watch the British movement at King’s Ferry; the British were rebuilding Stony Point with a new design (courtesy of Capt. Patrick Ferguson) and repairing any damage at Verplanck from the Continental bombardment (minimal). They didn’t sally out of either point, but by August 7, Crown boats were getting bold again.

Col. Rufus Putnam (commanding officer of the 5th Massachusetts) had been assigned to command the 4th Light Infantry Regiment and ordered to join Wayne at Fort Montgomery. Putnam, a distant cousin of Gen. Israel Putnam, and noted above as one skilled in engineering, was used frequently by Washington and Wayne for his abilities in that field as well as reconnaissance. At Fort Montgomery, he put his skills to use. As it was evident Wayne’s Corps was staying put for the time being, they would need some defensive works. Writing to Washington on August 8, he informed the commander-in-chief that he had “Nearly Compleeted a Circular Flash [fleche] … which Rake[s] the River from Anthonys Nose to Fort Clinton,” with one of the three embrasures pointing “up the River,” just in case a British vessel got past them. His timing was fortunate: he informed Washington that “the Enimy have a Roe Boat up as far as Salisbury Island,” which was only a mile and a half away. Despite the likely presence of the Light Infantry guard boats, we have no evidence of any further activity that week, though the tension of each side sizing the other up can be imagined.[9]

Putnam, ever busy, brought some of his regiment to gather food – a decent amount, too – at Peekskill on August 19 where twenty-three “wagon-loads of forage were brought off from the vicinity.” Such activity did not go unnoticed by the British, whose “galley,” stationed in the bay, “and one of the … gun-boats fired a number of cannon-shot at the party, but did them no harm.” Perhaps annoyed at their inability to halt the foragers, just two days later after dark on the 21st, the “enemy’s guard-boats came as far up the river as Anthonys Nose, and fired several shot at the camp of our light infantry.” If the battery at Fort Montgomery or Wayne’s guard boats returned fire, it was never recorded.[10] Once again, Benjamin Gilbert found himself alarmed due to a sighting of the enemy, this time on the 5th of September: “A party of men was sent to Peeks Kill to Drive off some men that weir landed their but they [were] gone before they got there.” What the British accomplished in this brief landing, if anything, is unknown.[11]

Nearly three weeks later, on September 24, General Wayne cancelled his meeting with Washington. His foot was bothering him; whatever he did to it prevented his comfortably riding a mount. Yet there was another reason the general stayed at Fort Montgomery: “the appearance of the Sixteen Gun Sloop of War [HMS Vulture], with a Galley & a few boats round the Dunderberg point.” Determined to “remain in quarters” until a clear picture of Crown intentions developed, Wayne had the Light Corps put on alert:

As a ship and one or two Galleys with some boats has appeared in View on th[is] side of Dunderbarge Point the Gen’l Wishes Every Officer & Soldier to be attentive to hold them Selves in Readiness for action in Case any attempt should be made by the Enemy which is Rather more wished than Expected.

This was the largest enemy movement towards American lines since the Storming of Stony Point. Wayne, always itching for a fight, was undoubtedly pleased by the prospect of another chance at the enemy, but alas, once more, no shots on either side are recorded as having been fired, and the threat of the small but armed fleet appears to have dissipated.[12]

The situation on land began to change. Occasional bouts of activity at King’s Ferry throughout September, namely the destruction of some of both Stony and Verplanck’s outworks, convinced Washington that the enemy was planning some movement, or was at least making the appearance of such. The Light Infantry began to break camp and become a more mobile force, ready to screen, strike, or do whatever circumstances required. The next two months would see them marching and countermarching along the Hudson, first in Haverstraw, then as low as Teaneck, New Jersey. Someone else would have to patrol the Hudson, and so while assenting to Wayne’s request for “the addition of two more light field pieces,” Washington asked Wayne to hand over his boats to “Genl [Israel] Putnam, who will keep them employed in the same service.” Those boats Wayne had that were not guard-boats, such as the “Whale-Boats & others,” he was to “have delivered to the Quartr Mastr Genl [Nathanael Greene].” At the same time, the commander-in-chief wrote to General Putnam to inform him that “Genl Wayne is about to move his Camp – I have desired him to mention to you the affair of the guard Boats – you will be pleased to take the direction of them and employ ‘em in the same service as they have been heretofore.”[13]

On October 7, about a week after Putnam received his boats, a British guard boat fell down from King’s Ferry to Grassy Point, a mile and a half below on the western shore (still a hamlet of the same name in Stony Point). Her presence excited the Americans: “There was a cannonade between our infantry at Grassy Point and one of the enemy’s guard-ships, when the latter was driven from her moorings.” Whether it was Col. Ann Hawke Hays’ 2nd Regiment Orange County Militia or members of the Corps of Light Infantry who fired on the boat is unknown; only General Heath recorded this skirmish, a very small, but definite, American victory (Haverstraw Village was a frequent target and that may have been the boat’s intent). Four days later, he reported another skirmish: “There was a cannonade in the river between the American and British gun boats; but no damage was done.” Regrettably, we don’t know where exactly this action of October 11 took place, but Putnam’s boats were seeing a lot more recorded action in one week than Wayne’s seem to have in two months. Five days later, on the 16th, there was another action. Once more, Heath provides the details: “Just before sun-set a galley and several of the enemy’s gun-boats came up the river as far as Fort Montgomery [the farthest any British vessel is recorded as having advanced up the Hudson for the remainder of the war], and fired a number of shot at some of our boats, and at the troops on the west side of the river; the Americans discharged some muskets from the banks at the boats, and the latter returned down river.”[14]

The war on the Hudson seemed to be heating up once again, but suddenly on October 21, the British evacuated their posts at King’s Ferry. The war was shifting to other quarters, namely the South, and after months of stalemate peppered with the occasional burst of activity, the boat standoff was at an end. The British withdrew to New York, bringing their guard boats, who would never again see so much activity in the Lower Hudson Highlands-Upper Haverstraw Bay region. The Continental Army, however, maintained theirs; West Point was growing in importance, and a stable presence on the water was essential for American security of both that post and the newly reoccupied King’s Ferry, both of which were maintained until the cessation of hostilities in April 1783.

[1] Rebecca D. Symmes, ed., A Citizen-Soldier in the American Revolution: The Diary of Benjamin Gilbert in Massachusetts and New York (Albany: New York State Historical Association, 1980), 51-52.

[2] For ship names, Master’s Log, HMS Vulture, The National Archives, United Kingdom, (hereafter “NA,” ADM 52/2073; William Heath to George Washington, June 30, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0254, note 1. Hereafter, Founders Online will be designated by “FO.” The ruins of Fort Montgomery, lost by the Americans on October 6, 1777, are on the north side of the junction of the Hudson River and Popolopen Creek, a current New York State Historic Site. It was used by Wayne as the Light Infantry’s home from June thru September 1779. Dunderberg Mountain is the highest ridge in present Rockland County: it is three miles south of Fort Montgomery, three miles north of King’s Ferry, and opposite Peekskill Bay. Sandy Beach is adjacent to Fort Montgomery on the river and is in today’s town of Fort Montgomery, roughly half a mile above the fort.

[3] Heath to Washington, July 10, 1779, FO, http://founders.archives.gov/Washington/03-21-02-0342, note 2.

[4] Pension Application of Seth Kellogg, September 18, 1818., National Archives and Records Administration, S. 42776, http://fold3.com/image/24633079; Pay Roll of Seth Kellogg, http://fold3.com/image/17417901; here Kellogg is listed as “pris: 14 July 79;” Muster-Table of HMS Vulture, NA, ADM 36/9053. The details of the capture are unknown; neither is it known whether this guard boat was the one received by Heath the day before. My thanks to historian Todd Braisted for answering my inquiries about this episode and supplying information on the Vulture.

[5] Michael J. F. Sheehan, “The Unsuccessful American Attempt on Verplanck Point, July 16-19, 1779,” Journal of the American Revolution (December 10, 2014), https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/09/the-unsuccessful-american-attempt-on-verplanck-point-july-16-19-1779/. In the days following Stony Point’s capture, the Americans ended up losing one boat, a galley, trying to withdraw the captured supplies into the Highlands, but as the vessel was not a guard-boat, she is outside the scope of this article.

[6] General Orders, July 19, 1779, FO, http://founders.archives.org/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0460; John U. Rees, “’The uses and conveniences of different kinds if Water Craft:’ Continental Army Vessels on Inland Waterways, 1775-1782,” http://scribd.com/doc/208475142/The-uses-and-conveniences-of-different-kinds-of-Water-Craft-Continental-Army-Vessels-on-Inland-Waterways-1775-1782, 22, 52.; “Return of Boats at this post fit for service with Oars,” West Point, July 29, 1779, and Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, reel 192, vol. 3, 113, 151.

[7] George Washington to Anthony Wayne, July 20, 1779, FO, http://founders.archives.org/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0487.

[8] The frequent use of soldiers from the 5th Massachusetts in this article is entirely coincidental, yet proves just how involved that unit was in the Hudson Valley during the period. Vaughan’s writing is atrocious, so the reader will excuse that I have found a middle ground in making him legible while still maintaining the exactness of his account. Virginia Steele Wood, ed. “The Journal of Private Zebulon Vaughan: Revolutionary Soldier 1777-1780,” Daughters of the American Revolution Vol. 113, No. 2 (February 1979), 324, http://services.dar.org/members/magazine_archive/download/?file_DARMAG_1979_02.pdf; Lewis Nicola to Joseph Reed, August 31, 1779, in Samuel Hazard, ed., Pennsylvania Archives, Series I, Volume VII (Harrisburg: Joseph Severns & Co., 1853), 674-5.

[9] Rufus Putnam to Washington, August 8, 1779, FO, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0063. Salisbury Island is today’s Iona Island, renamed in the nineteenth century. So far as we know, the guard boats of the Light Infantry were likely docked in the Popolopen Creek. My thanks to Grant Miller, Site Manager of Fort Montgomery State Historic Site for his help on the guard boats and Putnam’s Battery.

[10] William Heath, Memoirs of Major General Heath by Himself, William Abbatt, ed. (New York: William Abbatt, 1901), 198. As of this writing, precious little is known about Putnam’s Battery. The author’s educated guess is that the battery was manned and filled with the light field pieces attached to the Light Infantry under the command of Capt. James Pendleton. Considering the nature of light infantry, it is unlikely the guns at the battery were heavy garrison pieces. Nor do we know if the battery every fired in anger.

[11] Symmes., A Citizen-Soldier, 57.

[12] Anthony Wayne to Washington, September 24, 1779, FO, http://founders.archives.org/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0416; “Orderly Book of Captain Robert Gamble,” Collections of the Virginia Historical Society, New Series, XI (1892), 248.

[13] For one example regarding the withdrawal of the works at King’s Ferry: Patrick Ferguson to Sir Henry Clinton, September 18, 1779, in “An Officer Out of His Time: Major Patrick Ferguson,” Howard H. Peckham, ed. Sources of American Independence: Selected Manuscripts from the Collections of the William L. Clements Library, Vol II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 328-9; Washington to Wayne, September 30, 1779, FO, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0480 and note 3 of the same.

[14] Heath, Memoirs, 202-3.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...