What do an American Revolution prisoner of war accused of being a spy, a first born scion of an established wealthy New England family, and Machias Seal Island, a lonely, wind-swept chunk of rock in the Gulf of Maine all have in common?

The American Revolution in Maine has been described as a quasi-civil war with conflicting loyalties, harsh realities of survival and vengeful retributions of justice and payback.[1] For two colonial down east Maine men and their families, the war brought opportunities but also major challenges to their established ways of life. It forever altered the social, economic and cultural fabric of the area as well as their own personal interactions. The two men, born within a year of each other, came from different backgrounds but shared many similarities.

Jonathan Lowder came from a middle class Boston family. His father was a peruke maker for Gov. Francis Bernard and a messenger rider on the Boston to Connecticut post road. Lowder’s grandfather had been a tailor and ran a tavern, and his great-grandfather had been a ship captain. Jonathan was veteran of the French and Indian War and saw action as one of two trusted couriers for Bernard’s official correspondence back and forth from Boston to Crown Point, New York. That was where he met up with Thomas Goldthwait, paymaster for Gen. Jeffrey Amherst’s forces in New York. When Goldthwait became commander at Fort Pownal in the mid-1760s, he recruited Lowder and many others to come to down east Maine. Lowder became gunnery officer at the fort. When the fort was destroyed in 1775, he moved upriver and worked with the Indian trade until he was named official Massachusetts Truckmaster to the Penobscot Indians in either late 1776 or early 1777.

Jedidiah Preble Jr. was the first-born son of Gen. Jedidiah Preble of Falmouth, present-day Portland. He was born in York, Maine in 1734, a year after Lowder. He married Miss Avis Phillips of Boston in 1761. He was a poet with the gift of an exceptional memory.[2] The Prebles had long been established in New England and the general was a veteran of the successful siege at Fortress Louisburg in the 1740s. By the end of the French and Indian War, General Preble was commander of newly built Fort Pownal on the Penobscot River. His sons, Jedidiah Jr. and John, were linked to the region as well, having moved their families to the fort and involved themselves with the Penobscot Indian truck-trade. This is where Jonathan Lowder and Jedidiah Preble Jr. met.

By 1779, however, things had dramatically changed for both men. Jonathan Lowder celebrated the birth of his daughter Avis in June at the crude structure at the head of tide on the Penobscot River just below Mt. Hope that he used as his official government-run Truck-house to supply Penobscot Indians with food, gunpowder and lead shot. But by that fall, he was force-marched to Quebec as prisoner of war under suspicion of being a spy.[3]

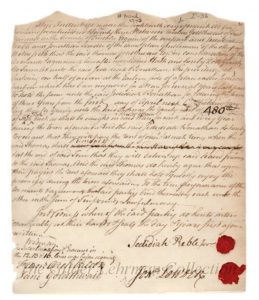

Which brings us to Jedidiah Preble Jr. He had worked at Fort Pownal under both his father and Colonel Goldthwait, as did his brother John. At times, each Preble son was the official Massachusetts Truckmaster to the Penobscot Indians. Amidst political intrigue, General Preble was replaced in the mid-1760s at Fort Pownal by Goldthwait, who then recruited Lowder and others from Boston and brought them down east. This is where and when Lowder and Jedidiah Jr. met. Both men, interested in economic opportunities available in the area, co-leased a fish weir from Goldthwait. This joint venture was not one of two young men just starting out; both men were nearly forty years old and Preble Jr. was the father of four children. The agreement, signed March 18, 1773, was witnessed by Francis Archibald and Goldthwait’s daughter Jane. It gave them privilege of building and operating one half of a fish weir at the eastern side of Cape Jellison harbor for three years. There was a yearly rent of 480 pounds of fresh fish to be paid to Goldthwait. If needed, they could build on the land. To bind themselves to the agreement, they had to produce £10. The weir was likely the half-tide type that extended from shore to shore to catch alewives and shad. It is not clear if this venture proved profitable, although credits for Lowder at the Fort Pownal store resulted from barter of several pounds of fish.[4]

This business and personal relationship continued into the contentious pre-war years. Preble Jr. as official Truckmaster received numerous complaints against him. This tested Lowder and Preble Jr.’s friendship and business relationship especially when the Penobscots made known their preference for Lowder to be their Truckmaster. By 1775, the situation deteriorated enough that people were hard pressed to name who actually ran Truckhouse operations. Preble Jr. was accused of lying in bed until ten o’clock most mornings, treating the Penobscots with great indifference, and leaving for days or weeks at a time as they waited for their supplies. He was dismissed by the end of 1775 and Lowder was appointed in his place at some point the following year, certainly by early 1777, which must have further strained their relationship. Jedidiah Jr. may have considered Lowder and Goldthwait as allies plotting against him, thus strategically against his father and their earlier intrigue. Political differences may also have created a wedge between them, although little record of either man’s position is evident. Later sources refer to Preble Jr. as a British sympathizer, even an outright Tory, and this may have led to his dismissal or it may stem from post-war historical revisionism. In November 1775, the Penobscots demanded that the Massachusetts General Court confirm their choice of Lowder as Truckmaster. On November 22, Lowder himself penned a letter for them addressed to Capt. John Lane where they reiterated their numerous complaints. The court replied that it had been a mistake to name Preble Jr. and that an Indian interpreter named Andrew Gilman would thenceforth be available at the Penobscot Falls Truckhouse to deal with them. It also said when the court once again went into session, they would name a suitable Truckmaster to fit their needs. There was no mention of Lowder, who likely had been operating as unofficial Truckmaster at this time.[5]

Preble Jr. later filed depositions against Lowder as Truckmaster, although this may have been at his father’s insistence or have stemmed from his own misfortune with the position. Yet even throughout this conflict, Jedidiah Preble Jr. and Jonathan Lowder appeared to remain connected with each other, perhaps even on somewhat friendly terms. Lowder may have provided assistance when Preble Jr. learned that one of his daughters and her maid had arranged to elope with two local native Penobscot men. The rendezvous was prevented and the daughter quietly sent westward from Penobscot.[6]

No longer Truckmaster after November 1775, Jedidiah Preble Jr. used the opportunity to temporarily leave the area. There is a record of a Jedidiah Preble from Portland, Maine as a private aboard the galley Congress, part of Benedict Arnold’s American fleet on Lake Champlain. It was likely forty-two- year-old Jedidiah Preble Jr. rather than his son Jedidiah Preble III, who was just eleven at the time. Congress, under command of Capt. James Arnold (no relation to Benedict) fought valiantly at the Battle of Valcour Island in October and helped successfully delay the British invasion attempt down through New York during 1776. The vessel was Arnold’s flagship for the fleet and saw heavy action; Benedict Arnold himself personally aimed many of her cannon during the fight. Vastly outgunned, Arnold had to eventually run the vessel aground and burn her to keep it from the British. After the battle, Preble returned to Maine that winter or the following spring, likely to his father’s home in Falmouth. He had smallpox, which had been widely present among Arnold’s men at Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Arnold’s later treachery may have been why Preble’s service with him at Lake Champlain was not more widely known or why some questioned Preble Jr’s own political stance later in the war. Regardless, by spring 1777, Preble Jr. was back in Maine recovering from smallpox. As he recuperated at his father’s residence in Falmouth, he signed depositions critical of Lowder’s actions as Truckmaster. This may have been instigated by his father General Preble in the older man’s quest to have his son John Preble reinstated as Truckmaster.[7]

In his deposition, Preble Jr. stated that in 1775 he had been used by Jeremiah Coburn to convince his father to establish a guard force for Penobscot and that Coburn implied Preble Jr. would command it. The force was established, but command was given to someone else. Preble Jr. was mad when only one or two were sent to guard stores and the remainder did nothing except build Lowder’s Truckhouse structure below Mt. Hope. When Josiah Brewer’s general alarm about an impending invasion was sounded that year, it frightened everyone and plunged the countryside into chaos. Preble Jr. stated that Lowder claimed that if Brewer’s alarm had not answered any other good purpose, it had at least been the means of stopping more criticisms of Lowder Truckhouse operations, including one “damned” petition from resident Benjamin Wheeler.[8]

Preble Jr. made another deposition that fall where he testified that he accompanied Lowder upriver in the Truckhouse boat, the same vessel Preble Jr. had been forced to give up to Lowder for Trucktrade use. Some of the local ranger force accompanied them to guard Patrick Bow, prisoner accused of stealing beaver skins and other items from Lowder’s Truckhouse. Lowder delivered Bow for trial to Justice of the Peace Josiah Brewer. According to Preble Jr., Brewer said if he proceeded with Bow to trial, Brewer and Lowder would lose a considerable sum of money. He then offered the prisoner the option to enlist in Continental service, to which Bow quickly agreed. The case was thus settled, Bow returned any stolen goods and paid a fine and restitution to Lowder, which he did out of his Continental Army enlistment bounty just received. Preble Jr. was unhappy with this especially when, according to Preble, Brewer then stated this arrangement was of considerable advantage to himself (Brewer) and Lowder. Preble Jr. assumed they split any proceeds, since they were in partnership in many other ways including the Trucktrade. Except for Brewer’s statements regarding potential collusion (alleged by an openly disgruntled Preble Jr.) Bow’s resolution was legal and appropriate even if Preble Jr. felt otherwise.[9]

While Lowder ran his Truckhouse in 1777 and 1778, Jedidiah Preble Jr. and his wife Avis Phillips and their family lived in Castine. They had relocated there some time before the war. The Prebles were devastated when their young son John drowned within a stone’s throw of his father’s house in Castine in July 1777. The crushing loss was part of Jedidiah Jr.’s numerous woes that summer battling small-pox and involving himself with his father’s machinations against Truckhouse operations on the Penobscot.[10] In June 1779, the relationship between Lowder and Preble Jr. might have softened somewhat when Lowder named his new-born daughter Avis, most likely after Jedidiah Jr.’s wife.

The British capture of Castine (then known as Majabagaduce) and construction of Fort George in 1779 dramatically altered the region politically, economically and socially for the remainder of the war. Massachusetts responded with a large naval fleet designed to regain control of the area. After a series of missteps and incompetence, Massachusetts forces were trapped and routed in upper Penobscot Bay by timely arrival of a British relief force. All its vessels save two were destroyed by their own crews in a desperate flight upriver as far as present-day Bangor. The remaining two were captured. It was the worst American naval disaster until Pearl Harbor in 1941. It is not clear what became of Jedidiah Preble Jr. and his family during this period. Some sources refer to his Tory or Loyalist leanings, although the published family history disputes that. It is known that his daughter Nancy remained in Castine during British control as well as after the war. She married Francis Adams and had her eight children in the town.[11] Jonathan Lowder’s whereabouts are equally murky after the Penobscot Expedition. It is known he remained in the area for a time but by September 1779 his options for American Truckhouse operations with Penobscot Indians had been severely curtailed.

On October 12, 1779, Jonathan Lowder and a Captain DeBadie, possibly an Acadian, were in the midst of a 130-mile trek in two birch canoes from Machias by way of Eastern Maine’s lakes and streams. They had just reached Sunkhaze, a few hours from the Old Town Indian settlement, when a party of twenty-six Canadian Indians led by British agent Monsieur Lunier surrounded and captured them. Also taken captive were four native Americans and all of John Allan’s important correspondence; Allan was Superintendent of Eastern Indians and operated out of Machias. Lowder and DeBadie were carried first to Moosehead, then Quebec and then on to Halifax where he was kept prisoner on suspicion of being a spy. His granddaughter said Allan’s secret papers, carried in a fake sole in his boot, escaped discovery, yet other sources indicate at least some were confiscated. Lowder’s wife, Deliverance, still lived at the Truckhouse and feared her husband was dead upon learning of his capture. She received no news concerning him except that he had been carried off by native Americans. His granddaughter said that during Lowder’s imprisonment, the privilege of writing home was denied him. Massachusetts authorities learned of Lowder’s status in a letter from John Allan on October 20. He wrote that he had learned of Lunier’s capture of Lowder and DeBadie the previous week.[12]

The British in Quebec reported on November 1, 1779 that a scouting party to Penobscot returned with Colonel Lowder and Captain DeBadie (referred to as a French officer) who carried letters from Colonel Allan to Congress and others. Captured letters were sent to Lieutenant Governor Hughes of Nova Scotia for his and General McLean’s information, especially Allan’s note stating that the recent defeat at Penobscot had caused murmuring among native populations against America and their refusal to obey him. They also learned that anti-British native Americans were marching from St. John to join Allan. The four Penobscots seized alongside Lowder and DeBadie returned to their villages after promising their fidelity. The prisoners were sent to Halifax to relieve pressure, especially with regards to DeBadie; it was feared the French Acadian might be mischievous in Quebec. Lowder was accused of tampering with native populations; his granddaughter said the British considered him a spy.[13]

For Jedidiah Preble Jr. and his wife Avis and family, times were difficult in British-controlled Castine. For Jonathan Lowder, his capture and prisoner status put his own family at risk. Lowder’s wife Deliverance Cook and their baby daughter Avis were no longer safe at the Truckhouse structure on the Penobscot River below Mt. Hope. Lowder’s granddaughter reported that the Indians wanted their items back that they had pawned for supplies (pawning items in exchange for food or powder or shot was one of many services Truckhouses provided). With Lowder gone, Indians soon appeared and demanded back their items. With the help of next door neighbor Mrs. McPheters, baby Avis was safely handed out the back of the Truckhouse cabin through a small window and carried to safety while Indians ransacked the structure’s front room. According to Lowder’s granddaughter, Deliverance and Avis soon after relocated to Castine.[14] They most likely took shelter with Jedidiah Preble Jr., his wife Avis and their family.

Which brings us to 1782 or 1783, the date Jedidiah Preble Jr. died; the Preble family history is inconclusive on the exact year. Regardless, at this time the British controlled Castine and Deliverance and Avis Lowder resided there most likely with Preble Jr.’s family. It was late in the war and they had had no word regarding Lowder other than that he had been captured in the fall of 1779. Perhaps they learned at some point that he was at St. John, in present-day New Brunswick. It is possible Jedidiah Preble Jr. booked passage to Passamaquoddy Bay to reach St. John and work towards Lowder’s release. This voyage eastward for Preble Jr. is interesting in that he was thirty-nine years old, he lived in British controlled eastern Maine and he would have been limited in what he could do for movement or for business. Regardless, he booked passage on a sailing vessel bound for Passamaquoddy. The ship wrecked on Machias Seal Island, a small barren crop of rock less than ten miles southeast of Cutler, Maine and less than twelve miles southwest of Southeast Head on Grand Manan Island, Canada. Today the sixty-five acre island is a nature preserve and reportedly the only land territory still disputed between United States and Canada.[15]

After the ship struck, survivors scrambled ashore before Preble. When he attempted to land, the ship lurched in the rough surf and pinned his leg between open planks which slammed shut and shattered his leg. He was able to free himself and got ashore, where he lingered in great pain for nine days subsisting on birds. The family history says he died of exposure, possibly shock and/or gangrene. The remaining survivors managed to get to the mainland shortly after Preble’s death. It is not clear if his body was ever recovered.[16]

So was Preble Jr.’s trip to Passamaquoddy to help with Lowder’s release? And since Preble Jr. died when the ship wrecked, when did Lowder end his days of captivity and return to Maine? As early as 1781, Nova Scotia Lieutenant-Governor Sir Andrew Hammond had decided to send captured privateers away from Halifax before winter arrived, in order to reduce crown expenses and inconvenience, especially with the tremendous increase in Loyalist refugees arriving. Lowder, languishing in confinement at Halifax, may have been transferred to St. John around this time. London officials welcomed Hammond’s prudent measures and the practice continued for two more years, which puts all of this in the time frame for Preble Jr.’s assistance. This would fit with what Lowder’s great-grandson William Wilder Taylor Jr. wrote about Lowder for his Sons of American Revolution application in which stated Lowder had been a prisoner of war in Canada for two years. He had learned that as a young boy in the 1850s while sitting at the knee of his grandmother Avis Lowder Banks Taylor, Jonathan’s daughter.[17]

Determining the date for Lowder’s release from prison may be helped with information about his son, Jonathan Lowder Jr. His son’s gravestone located in the Veazie town cemetery indicates that ship captain Jonathan Jr. was lost at sea and declared dead February 28, 1815, aged thirty-four years. His death date indicates a likely birth date sometime in 1781 or possibly late 1780. How did Lowder go from being captured in October 1779 and held prisoner in Halifax in March 1780 to having his son born later that year or in 1781? Deliverance might have been pregnant before Lowder’s capture, which would put Jonathan Jr.’s birth at the earliest some time in June 1780. Being pregnant may have been further incentive for Deliverance to vacate the unsafe Truckhouse at Mt. Hope for the Preble family’s safety at Castine. With Jonathan Jr.’s birth, Jedidiah Preble Jr. would have had three additional souls at his house in British controlled Castine to feed and protect. This may have convinced him it was necessary to travel eastward to seek the freedom of his old business partner.

What makes this likely is what transpired after the death of Preble Jr. At war’s end, it is recorded that Jonathan Lowder resided at Castine with wife Deliverance and two children, daughter Avis and son Jonathan Jr. They would have another son, William, born there in 1785. When did Lowder get to Castine and under what circumstances? Did it have something to do with Preble Jr.’s fatal voyage to Passamaquoddy? Whatever the circumstances, Jonathan Lowder thenceforth looked after Preble’s widow Avis and their children, much like Preble Jr. had previously done for him. The Lowders took care of Avis and her family for at least three years until 1786, when she moved inland to her grown son’s residence. The historical records around all this are spotty and incomplete and sometimes colored by politically motivated agendas and narratives, especially after the war when many participants no longer lived and descendants burnished their ancestors’ war credentials and denigrated the actions of others. Many were declared outright Loyalists or Tories, never to be spoken well of again. The dearth of written records regarding people at this time, possibly by design, is also interesting. Perhaps that was the preferred outcome, in light of the political, social and economic upheaval these people faced. For the actual participants and their regard for each other, like Jonathan Lowder and Jedidiah Preble Jr., their connections of business, friendship and family may have overlapped and prevailed in spite of the turmoil and chaos of war in down east Maine.[18]

[1] See James S. Leamon’s Revolution Downeast: The War for American Independence in Maine (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 135-165.

[2] George Henry Preble, Genealogical Sketch of the First Three Generations of Prebles in America (Boston: David Clapp & Sons, 1868), 130-133.

[3] Mrs. Porter Wiley, “When Bangor was a Log Cabin and a Stockade” Bangor Commercial (September 24, 1912) in the James B. Vickery Papers, Special Collections, Fogler Library, University of Maine.

[4] “Land Indenture Agreement, Jedidiah Preble Jr. and Thomas Goldthwait – 18 March 1773” #GLC02437.00042 Gilder Lehrman Collection; Massachusetts Historical Society, The Papers of Henry Knox v1, 36; “Jedidiah Preble Jr.” Maine Historical Magazine v8 (1893), 90; “Thomas Goldthwaite” in Fred E. Crowell, New Englanders in Nova Scotia (Cambridge, MA: New England Historical and Genealogical Society, 1979), 481; Sandra Gordon Olson, The Archaeology of Fort Pownall: A Military Outpost on the Maine Coast 1759-1775, MA Thesis, University of Maine (1984), 124, 175, 189 note 8; Lee Hanson and Dick P. Hsu, Casements and Cannonballs: Archeological Investigations at Fort Stanwix, Rome, New York (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1975), 159; Alice V. Ellis, The Story of Stockton Springs (Stockton Springs, ME: Historical Committee of Stockton Springs, 1955); and Francis Archibald, Fort Pownall Wast Book 1772-1777: A Day or Waste Book Kept by Sergeant Francis Archibald Jr. (1750-1785), Penobscot Marine Museum, Searsport, ME, 19.

[5] John E. Godfrey, History of Penobscot County, Maine: The Annals of Bangor, 1769-1882 (Cleveland: William, Chase & Co., 1882), 521, 557; Mrs. Porter Wiley, “When Bangor was a Log Cabin and a Stockade”; “Memoir of Col. Jonathan Lowder of Bangor” Bangor Historical Magazine v6 (1886), 296; Alvan Lamson, The Christian Examiner and Religious Miscellany (New York: Crosby, Nichols & Co., 1857), 48-49; Massachusetts Archives v144, 353; John Howard Ahlin, Maine Rubicon: Downeast Settlers During the American Revolution (Calais, ME: Calais Advertiser Press, 1966), 35; and “The Baxter Manuscripts,” Collections of the Maine Historical Society (Portland, ME: Fred L. Tower Co., 1910) 14:341.

[6] “Jedidiah Preble Jr.” Maine Historical Magazine v8 (1893), 90; Massachusetts Archives 144:336; Centennial Celebration of the Settlement of Bangor – September 30, 1869 (Bangor, ME: Benjamin A. Burr, 1870), 34; “Castine and Penobscot Names, etc” Bangor Historical Magazine v1 (1885), 57; and Godfrey, History of Penobscot County, 521.

[7] Stephen Darley, The Battle of Valcour Island: The Participants and Vessels of Benedict Arnold’s 1776 Defense of Lake Champlain (Published by the author, 2013), 5, 88-89, 176; Patricia M. Hubert, Major Philip M. Ulmer: A Hero of the American Revolution (Mt. Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 40, 41, 42, 430-431; Steve Darley, personal communication with author, July 2016; and Preble, Genealogical Sketch, 141.

[8] Preble, Genealogical Sketch, 69; and “Jedidiah Preble Jr.’s deposition,” “The Baxter Manuscripts,” 15:163-164, 165.

[9] “Jedidiah Preble’s evidence,” “The Baxter Manuscripts,” 15:277-278.

[10] Preble, Genealogical Sketch, 134-136.

[11] Preble, Genealogical Sketch, 136.

[12] Frederick Kidder, Military Operations in Eastern Maine and Nova Scotia During the Revolution Chiefly Compiled from the Journals and Letters of Colonel John Allan (Albany, NY: Joel Munsell, 1867), 268-269; and Wiley, “When Bangor was a Log Cabin and a Stockade.”

[13] “Report Pages 73, 84, 123, 160” Sessional Papers of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada v5 (1888), 131, 132, 177, 543; “Report Pages 34, 36” Documents Relating to the Constitutional History of Canada 1759-1791, 1791-1818 (1889), 583; Godfrey, History of Penobscot County, 528; and Wiley, “When Bangor was a Log Cabin and a Stockade.”

[14] Wiley, “When Bangor was a Log Cabin and a Stockade.”

[15] Machias Seal Island, Atlas Obscura (http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/machias-seal-island)

[16] Preble, Genealogical Sketch, 133.

[17] John D. Faisbiy, “Penobscot 1779: The Eye of the Hurricane,” MHS Quarterly (1979), 108-109; and Official Bulletin of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution v7 No 2, October (1912), 30.

[18] Preble, Genealogical Sketch, 130-131; Godfrey, History of Penobscot County, 521; Centennial, 34; and “Castine and Penobscot Names, Etc.,” Bangor Historical Magazine v1 (1886), 57.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...