Samuel MacKay

The American invasion of Canada of 1775 failed during the following winter when the siege of Quebec City was raised by the arrival of British reinforcements from overseas. The rebels were pushed out of the province and driven south on Lake Champlain to take refuge in the fortress of Ticonderoga. For the 1777 campaign, the British planned to mount a major counteroffensive, and in preparation, scouting missions were dispatched to collect intelligence about rebel preparations.

Although no British or German regular troops went on the scout, three of the Revolutionary War’s participating groups were involved in the reconnaissance. The party’s leader was a Quebec loyalist, a former British regular officer who was accompanied by a handful of his Anglo associates. His deputy was a veteran Canadian officer of high reputation with several of his fellows and, as an essential element, Canada Indians from Akwesasne (St. Regis) and Lakes Nations’ Ottawas were involved.

The primary actor in the mission was a former lieutenant of the 60th Royal American regiment who had settled in Quebec after the British “conquest” named Samuel MacKay. He had been born in Transylvania during one of his Scottish father’s foreign military postings. Following his pater’s career choice, in 1755 Samuel purchased an ensigncy in the British 62nd Regiment, called the Royal Americans. Soon after the regiment was renumbered to the 60th, and by 1756 Samuel and his brother Francis were lieutenants in the Royal Americans. The brothers went to America and served with distinction at the disastrous battle of Ticonderoga in 1758, but the pair lacked the funds to advance in rank. When they went on half-pay in 1768, they chose to make their fortune in the newly-established British province of Quebec.

A sure way to make an entry into Canadian society was to marry a lady from a prominent family, many of whom were said to be all too eager to teach the newcomers the French language and make a match. Samuel won the favor of Marguerite-Louise Herbin, whose father, Louis Herbin, was a knight of St. Louis and had been the final commandant of Fort Saint-Frédéric at Crown Point.[1] While Marguerite’s dowry was modest, her family’s reputation led to Samuel’s appointment as a Montreal district magistrate, which admitted him into Quebec’s noblesse, that is, to the gentry.[2] This was followed by Samuel obtaining the lucrative sinecure as the deputy surveyor of the King’s Woods for the Royal Navy,[3] although this rather protected role failed to save him from being sued for the wrongful clearance of 200 trees from a woodlot in 1767.[4] Brother Francis also married a Canadienne and had a government career, but when his wife died unexpectedly, he returned to Britain in 1770 leaving his children with Marguerite-Louise and Samuel.[5]

In 1775, rebellion erupted in Massachusetts, and Samuel MacKay immediately volunteered his services. That May, the rebels raided Quebec’s Fort St. John’s, looted military stores, seized a King’s sloop, and carried off the small garrison. Montreal’s commandant sent a detachment including Samuel MacKay to chastise the upstarts, but the raiders had left, and the troops returned to Montreal. MacKay realized the fort was vulnerable to a rebel reappearance, and received permission to raise volunteers to re-occupy the abandoned works. In late May, his volunteers captured a party of rebel-allied Stockbridge Indians that was attempting to persuade the Canada Indians to support the rebellion.

MacKay’s men held the fort until Governor Carleton arrived in Montreal and sent a detachment of regulars as a garrison whereupon MacKay returned to Montreal and received the governor’s permission to raise a new party, which he did to the number of eighty; however, Carleton optimistically had them dismissed shortly thereafter, thinking there would be no need for them. When the rebels invaded the province, MacKay raised a new party of fifty Franco- and Anglo-Seigneurs to bolster Fort St. John’s defences, and they arrived there in late May. MacKay and his men were extremely active in patrolling the rebels’ siege lines, improving the fort’s works, bringing in deserters, and taking rebel prisoners.[6] When the garrison was forced to surrender on November 3, MacKay and seventy-nine Franco- and eight Anglo-volunteers surrendered along with the garrison’s regulars and McLean’s Highland Emigrants. The captives were sent south to Albany.[7]

Rebel general Richard Montgomery, who had commanded the fort’s siege, wrote to General Philip Schuyler, his superior in Albany, to warn that MacKay was “so inveterate a fellow” that he should not be allowed to return to Quebec.[8] Being a prisoner did little to curb MacKay’s impetuous nature, nor his belief in the Crown. When the Regulars and Emigrants were sent to Philadelphia as prisoners of war, the Anglo- and Franco-Canadians were retained in Albany and permitted to go at large whereupon MacKay quickly made a nuisance of himself by publically proclaiming loyalty to the Crown. On December 7, he was brought before the city’s Committee of Correspondence and accused of “several Instances of misbehaviour,” to which he readily confessed. He was temporarily removed from public exposure while the committee debated how to act. When he was permitted a review, the Committee gave him their instructions, but he was intransigent, noting that he was “the King’s servant,” and need not follow their commands, which resulted in his confinement. The Committee requested that General Schuyler remove MacKay from the city and county, whereupon he was discharged from his parole and sent to Lebanon, Connecticut. He and several other prisoners were soon forwarded to Hartford, where they were harshly treated by the citizenry. They made requests to the authorities for redress, including a memorial from MacKay to General Washington, but nothing was done. On May 19, MacKay escaped in the guise of a clergyman, but the attempt was unsuccessful, and he was captured by alert countrymen with his servant McFarland and their guide, John Graves of Pittsfield. The captors bound and severely beat MacKay before throwing the party into jail. The Hartford newspaper characterized MacKay as “infamous,” noting he was “lost to every principle of honor as to violate his parole,” despite the fact that Schuyler had discharged that obligation when sending him to Connecticut. When he recovered from his wounds, he and Graves made a second attempt on September 10. This was so secretive and well-executed that their fellow prisoners were as astonished as their guards. The following day, the Connecticut Courant reported the escape and described the pair:

Said McKay has a wife in Canada, is of light complexion, light coloured hair and eyes, considerably pitted with the small pox, has a long nose, is tall in stature, has a droll fawning way in speech and behaviour, uncertain what clothes he wore away; had with him a blue coat with white cuffs and lapels, a gray mixt colour’d coat, and a red coat white waistcoats, a brown camblet cloak lined with green baize, and a pair of brown corduroy breeches. Graves is short in stature, has long black hair, brown complexion, dark eyes, one leg shorter than t’other, appears rather simple in talk and behaviour; had a snuff colour’d surtout and coat, green waistcoat, and white flannel ditto, leather breeches and white trousers. Whoever shall take up and return to the goal in Hartford, the aforesaid McKay and Greaves, shall be entitled to 50 dollars reward for said McKay, and 20 dollars for said Graves, by Ezekiel Williams, Sheriff[9]

MacKay and Graves made their way to Canada, where the former was given a warrant to raise a company of Canadians for the upcoming campaign. As well, he received other assignments, including the leadership of a reconnaissance mission to Lakes Champlain and George.

Claude-Nicolas-Guillaume de Lorimier

The patrol’s second most prominent agent was a member of a renowned Canadian family which possessed a remarkable military background. His great grandfather had been a naval captain; his grandfather commanded a fort near Lachine; his father, whom he was named after, was a Chevalier de St. Louis, a captain and the commandant of Fort de la Présentation on the St. Lawrence. Young Guillaume was born in 1744 at Lachine and by the age of sixteen had already held two officers’ commissions. He served at Carillon (Ticonderoga) under Montcalm and had been on Ile Ste. Hélène off Montreal in 1760 when the French regulars burned their colors to prevent them falling into British hands.[10] At some point, Guillaume appropriated his father’s title of Chevalier, a common practice during the French regime.[11]

Guillaume and his brothers had served with the Seven Nations of Canada and mastered the two primary language groups ̶ Iroquoian and Algonkian ̶ and several dialects of both. Although the Chevalier had earlier earned Carleton’s displeasure when he made unauthorized purchases of Indian stores in the King’s name, the governor recognized the need to expand the Quebec Indian Department, and appointed de Lorimier a lieutenant[12] and interpreter at Kahnawake ̶ the most fractious of the Seven Nations’ communities.

De Lorimier’s attempt to recruit Kahnawakes for the defence of Fort St. John’s was disappointing, but he managed to arrive at the fort with a small contingent and joined a handful of Six Nations’ Indian Department rangers and parties of Six Nations’ and Mississauga warriors.

Proving his linguistic and leadership skills, the Chevalier led a scout of four Lake of Two Mountains’ Algonquins south on the Richelieu River to Missisquoi Bay on August 22 where they discovered a bateau hidden under some branches. When they launched the craft to return to the fort, they were challenged from the shore and shots were exchanged. The next day, an investigation revealed they had killed Remember Baker, a notorious Green Mountain Boys captain from the New Hampshire Grants.[13] Lorimier had participated in one of the first combats of the rebellion in the north.

On September 6, the Chevalier and his brother Verneuil joined some one-hundred Six and Seven Nations’ warriors in a hot action that repelled the rebels’ first landing attempt at the fort. By Native reckoning, their losses were severe, and they noted that the regulars had failed to support them during the fighting, which prompted the Canada Indians to go home. The fort’s commandant was fully aware of the Natives’ importance, and asked the Chevalier to persuade them to return. When de Lorimier caught up with them, a council was assembled, during which a Huron warrior from Lorette asserted that the rebels had the fort so thoroughly blockaded that no one could get through. De Lorimier took his leave and disproved this claim by cleverly infiltrating in and out of the fort, then returned to the council. His feat and persuasive oratory convinced the Kahnawakes and they returned a party to the fort.

In late October, de Lorimier went to Montreal to persuade Carleton to relieve the siege of Fort St. John’s. The governor accepted the challenge and assigned Chevalier to command some 400 Canadian militiamen for an attack across the St. Lawrence on rebel-occupied Longueuil, but the attempt was a disaster, and several days later, the fort succumbed. De Lorimier declined to accompany Carleton to Quebec City, and instead obtained permission to retire upriver to assemble a war party to make a strike at a suitable opportunity; however, he remained in Montreal for a considerable time, and so upset the rebel occupiers by agitating the citizenry that he was forced to flee to the upper country.

After collecting a supply of powder and ball from the British post at Oswegatchie, he and a Native companion recruited over 200 Mississauga, Akwesasne, Six and Lakes Nations’ warriors. These Natives and a company of regulars laid siege to the rebel post at The Cedars. De Lorimier was prominent in forcing the surrender of the garrison and gaining a victory over a rebel reinforcement at Quinze Chiens. He was also a signatory to the cartel whereby the prisoners taken in the two actions were to be exchanged for British and Canadian captives. As a punishment for his bold activities, the retreating rebels slaughtered his mother’s poultry and cut down her orchard, but their attempt to fire her house failed.

The siege of Quebec City was raised by the arrival of a strong reinforcement from Britain, and the rebels pushed upriver to the Richelieu. When de Lorimier crossed the St. Lawrence, he joined Carleton and his senior officers, including Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne, the army’s commander, and was given command of all the assembled Natives with orders to cut off the rebels’ retreat. Despite moving at speed, his detachment was outpaced; however, this assignment confirmed that he was among the most important of the loyal Canadians. After the rebels were finally expelled from the province, he was chosen by the governor to deliver an official pardon to the Kahnawakes for their community’s frequent disloyalties.

When the governor launched his counter attack on Lake Champlain, de Lorimier served under his friend, the governor’s nephew Capt. Christopher Carleton, who had lived at Kahnawake for several years and become acculturated to the Native way of life. Prior to the expedition’s launch, de Lorimier was instructed to collect warriors from Akwesasne and the Lake of Two Mountains, and during the advance he and his party effectively sniped at General Benedict Arnold’s row galley in the Valcour Island action.[14]

After Carleton’s expedition completed the destruction of Arnold’s fleet of gunboats, his force took post at Crown Point and conducted a few reconnaissances, but the governor decided that the season was too advanced to attack Ticonderoga, and he withdrew his army to Quebec.

Guillaume de Lorimier had proven to be one of the most significant junior officers in the Quebec Indian Department ̶ indeed, in the army in Canada. He was brave, resourceful and talented. If any of his characteristics deserved criticism, it may have been his brashness and tendency to gasconade.

Samuel MacKay and Guillaume de Lorimier undoubtedly knew each other, as Quebec society was small and both were of the gentry. As well, they had military careers in their past, and immediately volunteered for service when the province was threatened. They had served together during the defense of Fort St. John’s, although apparently did not share missions. Both men had large reputations for their adventurous spirits and accomplishments, and the egos to match. To judge from their reports of the scouting mission, they may have viewed each other as competitors.

The Mission

When Burgoyne received Carleton’s permission to return to England to visit his ailing wife and attend his seat in Parliament, Gen. William Philips became the army’s acting commander and Carleton’s Chief of Staff.[15] That winter, the governor instructed Philips to send a scout south on Lake Champlain to gather intelligence about the rebels’ various posts. MacKay’s memoire states that Philips selected him to lead the mission, which he “accepted with pleasure.”[16] Historian Paul Stevens advises that Carleton had stipulated that the scouts “should not shoot or otherwise harm anyone they encountered, rebel or not.”

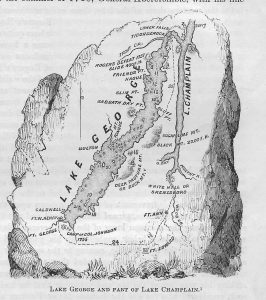

De Lorimier recalled, “Early in 1777, General Philips said to me in the presence of Mr. MacLine and Mr. McKay that he would like to know what was going on at Crown Point and Fort George. He said that between the two lakes [Lake George and Lake Champlain] there lived a Loyalist named Adams, and that one could obtain true information from him. I said that I knew the man and that I could undertake the journey. Mr. McKay said that he would come along with me as well, and that he would bring a party of whites. We decided to slip out of Montreal quietly and go to St. Regis [Akwesasne], find Indians to accompany us, not wanting to trust the Caughnawagas [Kahnawakes].”[17] Thus, the Chevalier presented MacKay as his deputy, not the other way around.

De Lorimier recalled, “Early in 1777, General Philips said to me in the presence of Mr. MacLine and Mr. McKay that he would like to know what was going on at Crown Point and Fort George. He said that between the two lakes [Lake George and Lake Champlain] there lived a Loyalist named Adams, and that one could obtain true information from him. I said that I knew the man and that I could undertake the journey. Mr. McKay said that he would come along with me as well, and that he would bring a party of whites. We decided to slip out of Montreal quietly and go to St. Regis [Akwesasne], find Indians to accompany us, not wanting to trust the Caughnawagas [Kahnawakes].”[17] Thus, the Chevalier presented MacKay as his deputy, not the other way around.

MacKay reported leaving Montreal on February 20 and arriving at Akwesasne, where he and Capt. Alexander Fraser, the deputy commander of the Quebec Indian Department, held a council with the Natives. Fourteen warriors were persuaded to follow him. Four days later, he set out with “Messrs. Lorime [Chevalier de Lorimier], St. Amande, La Ronde [Louis Thibaudiere de Denys de la Ronde], Graves and fourteen Indians.”[18]

De Lorimier recalled, “We decided to slip out of Montreal quietly and go to St. Regis, find Indians to accompany us, not wanting to trust the Caughnawagas. So I ended up with lieutenants Soumandre [probably Jean-Pascal Soumande Delorme] and La Ronde, both from the Indian Department, twelve Indians from St. Regis and ten ‘palefaces.’”[19]

MacKay’s note for February 26 states, “I Persued my Route and now the Party was increased to Thirty being joined by some Indians.” Stevens advises that these new additions were eight or ten Ottawa warriors, but where they had come from is a mystery. Perhaps they were a Lakes Nations’ delegation visiting Akewsasne and eager for some adventure. Stevens also reports that Lorimier’s “palefaces” were three Anglo- and three Franco-volunteers.[20] MacKay’s report continued:

I opened my orders the same day and thought it would be more prudent to mention the places only we were going to as I was apprehensive the Indians might have communicated the General’s Intentions to some of their People who followed us for some time and then returned back which the Indians were accustomed to do.

The next entry in his report was dated March 7:

Imagining I was near to Ticonderoga I explained by orders in full to the party and the General’s intentions and desired they would assist me to execute the orders of the General. The Indians refused to go in a body to examine the different posts, alledging they would certainly be cut off.

MacKay reported six days later,

Finding the Indians averse to going in a Body I proposed to divide in four different parties; one to go to Ticonderoga, One to Crown Point, one to Skenesborough, and one to Fort George. They agreed to go to three of the Places but objected going to Skenesborough.

This being agreed on, consented by the Indians we seperated, one party, Messrs. La Ronde and King with five Outawaugh [Ottawa] Indians with orders to go to Fort George.

On March 18 he detached two Canadians, “Messrs. Brancoinet and la Bonte[21] with three Indians with orders to go to Crown Point.” He did not say if these Natives were Ottawas. MacKay’s later account to Allan Maclean further defined the situation. “Three days march short of Ticonderoga, I divided in four different parties, which I separately detached, one to Crown Point another to Skeensburgh, another to Fort George, and the other which consisted of sixteen men commanded by myself I intended for Ticonderogo.” Note that in this description, Skeenesborough became a target again; however, he chose not to mention that the Natives refusal to operate in a single, large party had prompted his decision to divide into four separate scouts. In de Lorimier’s account, the Natives’ recalcitrance and the divisions of the party are simply ignored. The Chevalier was far more inured to such problems than MacKay. His account reads,

We crossed all the mountains in order to reach the mouth of Lake George where we arrived on the twentieth of March. Within an hour of our arrival who should come by but Adams along with two American soldiers who were driving some young horses toward Grande Pointe to pick up their food. We seized all three men and I had some difficulty in keeping the Indians from harming them; one Indian called me faint-hearted and said I was afraid of the enemy.

One of the men they took was Samuel Adams, the Loyalist they had been told to seek out for information. Adams gave this account to a friend several days later: “he with 2 others were going to Sabath day point with 13 Horses on ye west side the Lake & were Taken by Capt. McKoy with about 18 Cocknewago Indians, about 3 o clock afternoon five miles North of Sabath day point.”[22] Adams cites MacKay, not Lorimier who had claimed to know him personally.

MacKay’s report for the 19th sheds more light on this event:

My Party arrived at Lake George about nine miles from Ticonderoga at twelve o’clock in the day, we intended to wait until night in order to cross over Lake George to take a view of Ticonderoga, about three o’clock the Indians discovered some men coming towards us with horses – I did every thing that lay in my power to prevent the Indians from taking of them, as it would frustrate us from executing our Father’s [Carleton’s] will, but in spite of every thing I could do or say they would not comply with my orders. I then told them when I perceived that they would not listen to what I wished them to do, that if they promised to go with me to Ticonderoga, I would overlook their taking these men though they had forced me to act in this manner contrary to our Father’s instructions. When the Indians went after them I desired Mr. Lorime to see that they did not (use) any cruelties towards them. So soon as the Indians had taken those men they wanted to return home without executing any thing further.

MacKay had bowed to de Lorimier’s familiarity with Native ways. The Chevalier’s account continued,

Just then, I spotted seven men on the ice, but quite far out on the lake. So I put my hand on the Indian’s shoulder and said to him, “Here is the very chance you need to prove that I am a coward,” indicating the seven men out on the ice. I went on, “Choose five braves, and you and I will lead them to the attack.” At this, the Indian asked my pardon, but nevertheless he made up the party of seven men including ourselves and we went through the woods toward a place where the enemy would have to come near the shore. Once there, however, we saw that instead of being seven they were seventeen, all riflemen. I saw the obvious danger and said to the Indians, “Who is willing to act as leader of the party so that you will have nothing to reproach me with? Remember though, if one of you is willing to lead, I will be the first to follow.” One replied, “I will take the lead; I know this region, and the enemy whom we see is going to camp at Sand Point where we can surprise them tonight.[23]

MacKay’s report continued,

we discovered a Party coming down Lake George – Being frustrated in accomplishing the General’s intentions by the perverseness of the Indians we followed this party to Sabbath Day Point and took the Captain with seventeen men – The Lieutenant and four others being killed by the Indians notwithstanding their solemn promise to me before the attack that they would not hurt any of them, and one other made his escape supposed to be badly wounded. The Indians plundered the prisoners of their cloathing which I purchased of them again in part to cover the Prisoners from the cold.

Samuel Adams added.

soon after he [ Adams] was taken Capt. [Alexander] Baldwin came along with about 25 Men from Ticonderoga going to Fort George on the Ice. [T]he Indians concealed themselves in ye Woods until about 3 o clock at night. Capt. Baldwin with his men passed by to Sabath Day point where they made a fire[,] Ley down & went to sleep, when the Indians attacked them Killed 4 & took 20 which they carried off[,] but Mr. Adams being well acquainted with Capt. McKoy, he pleading that he was only an inhabitant did not belong to the Army obtained Leave to return after marching 30.[24]

Not mentioned in MacKay’s reports was a fortunate occurrence. In May 1776, seventeen-year-old Thomas Man, a member of a prominent Stillwater family and a pre-war militia lieutenant, had been brought before the Albany Committee of Correspondence as a suspected Tory. After his interrogation, he was dismissed as a person “incapable of doing any material damage to this Country.” His subsequent activities must have proven otherwise, as he was sent under guard to the State Convention in Kingston in November.[25] Man was returned to Albany, but by March 1778, his father worried for his safety and encouraged him to flee to Canada. During his trudge northward, he was intercepted at Sabbath Day Point by a detachment of rangers commanded by Captain Baldwin. Thomas’s father later reported, “The same night a party of loyalists and Indians under the command of Capt. Sam MacKay, from Canada, surprised & took the party, with whom my son repaired to Montreal.”[26]

Rebel ranger James Rankins deposed in his pension application,

[At] a place called Sabada Point on Lake George about midway between Fort George & Tyconderoga, they were surprised & attacked by a band of Indians and Canadians commanded by one Captain McCoy and [an] engagement ensued and Rankins with about 25 or 30 others were taken prisoners and four others killed, the remainder of the company escaped – Rankins & the other prisoners were taken to Montreal.[27]

An anonymous letter from Stillwater reported,

Wednesday last, at Sabbath day point, on Lake George, Captain Baldwin and sundry of his men, with Mr Cobbin, Thomas Maim [Man?], &c. were taken prisoners by a party of the Indians, Tories, and Canadians, to the number of 25, and ̶ carried we know not where ̶ John Lee of this place, and three strangers were killed and scalped: I expect trouble here this summer, for the Indians up the Mohawk river grow very fancy.[28]

MacKay noted that his party and the prisoners left the lake on March 20 to go to the appointed rendezvous to meet the other scouts. The next day, he reported,

Finding Samuel Adams, a Royalist who lives on the Landing place at Lake George not in condition to follow us, after getting from him every information I suffered him to return being afraid that by his not being able to march the Indians might kill him.

I told Adams that the only thing that could justify me in releasing him was that he should promise to be very particular in his attention to observe the Motions of the (Rebels) and to obtain all the information in his power relating to their numbers, &c, and that he was to embrace the first opportunity to convey it to the Generals in Canada.

We arrived at the place of rendezvous where we met Mr. La Ronde and his party with two prisoners they had taken between Fort George and Fort Anne. – Mr. La Ronde examined the situation of Fort George and the works about it and give pretty nearly the same account as Samuel Adams. I have examined none of the Prisoners that we brought nor has any of the Party.

A rebel militiaman’s journal entry for March 22 noted,

Rode out to ye Mills & to Mr Adams. at Evening he came in after being four Days with the Enemy, he with 2 others were going to Sabath day point with 13 Horses on ye west side the Lake & were Taken by Capt. McKoy with about 18 Cocknewago Indians, about 3 o clock afternoon five miles North of Sabath day point.[29]

MacKay’s report closed on March 30.

We arrived at Montreal with a Captain and twenty-one men Prisoners. I must observe that the Indians in prosecuting our route to Tyconderoga very much retarded us by idling away their time and in not following my orders of march, as a convincing proof of it I must take notice that we performed the same journey in ten days in returning which had taken us Twenty three days in going.

I was informed by Messrs. Lorime and St. Armande that it was firmly the intention of the young men among the Indians to strike a blow upon the Rebels as soon as I had reconnoitered the Post but falling in with these parties first they could not be restrained from executing /it/ before any thing could be done in relation to the object for which the expedition set out other than from Intelligence.

These events greatly alarmed the rebel garrison of Ticonderoga. Colonel Anthony Wayne wrote to the governor and council of Massachusetts on March 25,

Gentlemen:—A party of Cochnawago Indians, under the command of a Captain McCoy, of the British forces, have killed several of our people, and taken Captain Baldwin, with twenty-one men, prisoners, at a place called Sabbath-day Point, on the 20th instant, by which means the enemy, who are now all collected at Montreal, Chambly, St. John’s, and their vicinity, will be but too soon informed of the debilitated state of this garrison, which at present does not consist of more than twelve hundred men, sick and well, officers included, four hundred of which are militia from Berkshire and Hampshire, in your State, whose times expire in ten days—but this in confidence.[30]

Wayne wrote to Schuyler with some additional details:

It is the opinion of those who are best acquainted with Lake Champlain, that it will be navigable in the course of two or three weeks at farthest. It is, therefore, my duty to inform you that we have not more than twelve hundred men, sick and well, officers included, on the ground; four hundred of which are militia, whose times expire in ten days; nor from what I can learn, by the best authority, is there any probability of a sufficient number of troops arriving from the eastward, for a very considerable time, as few, if any of their regiments are near full, and great part of those who were enlisted have deserted or are straggling through the country. Add to this, that their officers seem seized with a general torpor (which can not be accounted for), especially at a time when every effort is absolutely necessary to push on the troops, and to give them some idea of duty and discipline previous to their entering into action.

I must beg, sir, that you would once more endeavor to rouse the public officers in those States from their shameful lethargy before it be too late. I do assure you that there is not one moment to spare in bringing in troops and the necessary supplies. The few men I have on the ground are put to hard, very hard duty; but they go through all with a ready cheerfulness, conscious of the pressing necessity.

Whilst I am writing, Mr. Adams, who lives at Lake George landing, has arrived almost spent. He, with Captain Baldwin of the Rangers, belonging to Stillwater, and twenty-one men, were made prisoners at Sabbath-day Point by a party of Cochnawago Indians and Canadians, amounting to about twenty, under the command of Captain McCoy, of the Regulars. Lieutenant Henry, with five others belonging to Colonel Van Schaick’s regiment, are killed. Adams and two of the soldiers were taken last Wednesday afternoon. Captain Baldwin and the other prisoners were surprised and taken asleep, at the Point, about three o’clock the next morning. Lieutenant Henry defended himself with great bravery for a considerable time, dangerously wounding two of the Indians with his navy [dirk?]. He at last fell, worthy of a better fate. Adams says he informed him of another party hovering round this post; but, if that was true, I believe they would not have mentioned it. He further says that the Indians came by the way of Omergotchy, and that he was set at liberty on account of being weakly and a former acquaintance of Captain McCoy, who also informed him that the enemy are collected at St. John’s, Chambly, and Montreal, and their vicinity. I have sent Captain Whitcomb, with a party of Rangers, to bury the dead, and hope soon to retaliate on the British butchers.[31]

*****

Both MacKay and de Lorimier went on to serve prominently during Burgoyne’s expedition. After abandoning command of his company of Canadians, which went on to serve under St. Leger at Fort Stanwix, MacKay joined Burgoyne as a volunteer. This decision roused Carleton’s anger and resentment. MacKay served in an unknown capacity at the Hubbardton battle, and again as a volunteer in the Bennington battle.

After Bennington, he was given command of the “Loyal Volunteers,” which had been raised in eastern New York by Francis Pfister, another Royal American’s half pay officer. Pfister was killed in the Bennington battle and none of his officers were sufficiently confident to take command, so Burgoyne appointed MacKay the captain-commandant. This small battalion was very active during the remainder of the campaign, but when MacKay and most of his men were cut off from the main army and went to Ticonderoga, Burgoyne was enraged. When MacKay arrived in Quebec, he discovered that Burgoyne’s account of his “desertion” had preceded him and was entirely accepted by Carleton who refused to recognize his extensive services, and removed him from command of his small battalion. MacKay protested to the home government, but tragically died before he was exonerated and promoted to major.

De Lorimier also served at Bennington with the Native contingent and was grievously wounded in the leg. He was out of action until July 1780 when he led a raid against Fort Stanwix that yielded thirty-eight prisoners and ten scalps; however, the rigorous activity had been too much for him and he collapsed from exhaustion while delivering his report to Gov. Frederick Haldimand in Quebec City. Subsequent medical treatment almost killed him, but his robust constitution won out, although his war was over. Nonetheless, he continued to lead a fulfilling life, marrying a succession of three women and siring twelve children. As well as his role as the Indian Department agent at Kahnawake, he served for four years as a member in the Lower Canadian House of Assembly. When war against the United States broke out in 1812, he was appointed resident captain to the Kahnawakes and other Iroquois Indians. At age sixty-nine, he fought in the battle of Châteauguay, and when the government established four companies of Embodied Indian Warriors, de Lorimier was appointed deputy superintendent and ranked as a major. He died in 1825 at Kahnawake, a man of great accomplishment.[32]

[1] Pierre-Georges Roy, Hommes et choses du Fort Saint-Frédéric (Montreal: Editions des Dix, 1946) 179. http://www.ourroots.ca/toc.aspx?id=3315&qryID=7ac8f738-76b1-4e16-9048-f9607fe113ef (accessed December 31, 2016).

[2] “Nobility of New France,” https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noblesse_de_Nouvelle-France (accessed December 31, 2016).

[3] Alexander V. Campbell, The Royal American Regiment, An Atlantic Microcosm, 1755-1772 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 203-04.

[4] Hilda Neatby, “Benjamin Price,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography (hereafter DCB), III.

[5] Francis (Frans) MacKay, https://www.genealogieonline.nl/en/west-europese-adel/I1074001852.php (accessed April 18, 2017).

[6] Gavin K. Watt, Poisoned by Lies and Hypocrisy – America’s First Attempt to Bring Liberty to Canada, 1775-1776 (Toronto: Dundurn, 2014), 51-52.

[7] Samuel Mackay to Allan Maclean, Montreal July 20, 1778. McCord Museum, McGill University, Montreal; Horst Dresler and Deb Goodman, Hold Fast – The Siege of Fort St. John’s, 1775 (Woodstock, VT: Anything Printed, 2016), 22, 31, 32, 62, 66, 87, 104, 117, 124. Dresler includes a list of the Franco- and Anglo-volunteers taken prisoner at St. John’s, ibid, 121 transcribed from Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), CO, Series Q, Vol. II, 284.

[8] James M. Hadden, A Journal Kept in Canada and Upon Burgoyne’s Campaign in 1776 and 1777, Horatio Rogers, ed. (Albany: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1884), Rogers’ footnote, 40.

[9] For the 1777 campaign, MacKay recommended a “Jean Grave” as his company’s surgeon. “List of Persons Recommd for Commissions – in the Canadian Corps, n.d.” LAC, Haldimand Papers (hereafter HP), MG21, WO28/10, Pt.1; Hadden, A Journal Kept in Canada, Rogers’ footnote, 40-43, which includes transcripts from The Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer of May 27 and September 23, 1776.

[10] Claude-Nicholas-Guillaume de Lorimier, At War with the Americans, Peter Aichinger, ed & tr. (Victoria, BC: Press Porcepic, n.d.), 11; Douglas Leighton, “Claude-Nicholas-Guillaume de Lorimier,” DCB, VI.

[11] C-N-G de Lorimier’s biography, DCB, VI. Leighton states that Guillaume’s appropriation of the title “Chevalier” occurred “since at least 1783.” His advice that this was a common practice for younger sons of the nobility during the French regime made me suspect Guillaume did so earlier. I have an unattributed letter written at Montreal on December 1, 1777 that is signed, “Chev. Lorrimier,” and mentions in passing “une Campagne avec monsieur Mckay d’une Fatigues pres que ausoy Considérable.” Consequently, I have employed the title “Chevalier” frequently.

[12] Quebec Indian Department records do not refer to the Canadian officers by a rank, but rather by the designation, “Monsieur.” Nor did they receive formal commissions from the governor. Paul Stevens theorizes that this was not an oversight, but a deliberate decision, as during this time period, Roman Catholics were not allowed to hold commissions in the British Service. However, these appointees were regarded as officers and received “a respectable five shillings a day.” Paul L. Stevens, “His Majesty’s ‘Savage’ Allies: British Policy and the Northern Indians During the Revolutionary War – The Carleton Years, 1774-1778,” a doctoral dissertation for the Department of History, State University of New York at Buffalo. XIII, 826; A 1778 return of the Quebec Indian Department listed several of the Canadiens as “Canadian Officers Messieurs, Interpreters Messieurs, Commissarys Messieurs.” Ontario Archives (hereafter OA), HP, AddMss21770, 134. Similar designations appear in Haldimand’s General Orders of 1783. OA, HP, AddMss21744, f.41.

[13] For Baker, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remember_Baker (accessed January 7, 2017).

[14] Lorimier, At War with the Americans, 27-61; Watt, Poisoned, 52, 66, 72, 73, 77, 86, 95, 99, 127-30, 141-51, 153, 154, 162-65, 173, 184.

[15] Robert P. Davis, Where a Man Can Go – Major General William Phillips, British Royal Artillery, 1731-1781 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), 48-49.

[16] Samuel Mackay to Allan Maclean, Montreal, July 20, 1778, McCord Museum, McGill University, Montreal.

[17] Lorimier, At War with the Americans, 61; MacLine is possibly Lt. Col. Allan Maclean of the Royal Highland Emigrants.

[18] Mackay to Carleton, March 31, 1777. transcribed in A History of the Organization, Development and Services of the Military and Naval Forces of Canada, etc…, with Illustrative Documents, Historical Section of the General Staff (3 vols, Ottawa: n.p., n.d.), 2:207-08.

[19] Lorimier, At War with the Americans, 61; Stevens’ exhaustive research suggests that St. Amande is St. Amande Soumande, one of many variant names for Jean Soumande Delorme. Stevens, Allies, endnote 11, XV, 2178. By process of elimination, this may well be the case; a Soumande de L’Orme was recommended to General Phillips as a lieutenant in his company of Canadians. “List of Persons Recommd for Commissions – in the Canadian Corps, n.d.” LAC, HP, MG21, WO28/10, Pt.1.

[20] It is noteworthy that Lorimier did not trust the warriors of his own community; Stevens, Allies, XV, 934. De Lorimier reported ten “palefaces,” but Stevens described six only. Assuming MacKay and Lorimier were an additional two, who/what were the remaining two?

[21] La Bonte is perhaps Jacques Benjamin Labonte born at Pointe aux Trembles, Montreal, 1747. http://www.ancestry.ca/genealogy/records/jacques-benjamin-labonte_39054224 (accessed January 7, 2017).

[22] Entry of March 22, 1777. The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin 1775-1778 (Bangor, Maine: The DeBurians, 1906); Alexander Baldwin was the captain in command of a company of Albany County rangers. Oddly enough, on March 27, his company and nine other ranger companies had been discharged. Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Vol XV, State Archives Vol. 1 (Albany: Weed Parsons, 1887) 148.

[23] Lorimier, At War with the Americans, 62. Sadly, his account of the action abruptly ends here.

[24] The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin, entry for March 22, 1777.

[25] Minutes of the Albany Committee of Correspondence, 1775-1778, James Sullivan & Alexander C. Flick, eds. (2 vols, Albany: State University of New York, 1923&25).

[26] “An authentic narrative of the sufferings of Isaac Man Esq. and his family,” LAC, AO1/27, [MG14], 99; Thomas was commissioned an ensign in Jessup’s King’s Loyal Americans in 1777. During Burgoyne’s expedition, he was a Secret Service operative who recruited a number of men. He was caught and jailed, but returned to Canada and continued in Jessup’s again in the Secret Service. On disbandment in 1783, he ranked as the fifth senior ensign of Jessup’s Loyal Rangers. Gavin K. Watt, The British Campaign of 1777 – Volume 2: The Burgoyne Expedition – Burgoyne’s Native and Loyalist Auxiliaries (Milton, ON: Global Heritage Press, 2013), 91, 102n20.

[27] Pension deposition of James Rankins of Getman’s Company of Tryon County rangers, S14255. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1800–1900, Record Group 15; National Archives Building, Washington, DC Prior to his capture, Rankins had a complex service history. He was drafted from Marks Demuth’s Tryon Ranging Company into Getman’s and sent to Ticonderoga to assist in the building of a floating bridge, which appears to be rather odd employment for a ranger. The company was dismissed in the Spring of 1777 and permitted to return home. He was in the process of doing so when captured; Neither Captain Baldwin or Rankins are found in Chris McHenry’s study Rebel Prisoners at Quebec 1778-1783 (self-published, 1981) indicating that they were exchanged before his records began; Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York. This source notes that Serjeant Joseph Graves, Baldwin’s Albany County Rangers who was captured Sabbath Day Point March 20, 1777 was paroled in the fall of 1778.

[28] Anonymous letter from Stillwater, March 22, 1777. North British Intelligencer; or, Constitutional Miscellany (Vol. V, Edinburgh: 1777), 370; one of the captured men was an Englishman named Joseph Clarke who had been in America for a year before being jailed in Albany from where he was forced to enlist. He then deserted, but had been taken up and was being escorted to jail in Albany. “List of Rebel Prisoners with a Letter of Cap. McKay,” May 13, 1777. HP, AddMss21841, f54. Thirteen captives were from the 1st New York Regiment, only four from Baldwin’s ranging company and two were Massachusetts soldiers. See also Judy Longley, “Account of a British Intelligence Expedition in 1777, and of its Prisoners,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol.122, No.1 (January 1991).

[29] The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin, entry for March 22, 1777.

[30] Col. Anthony Wayne to Governor Bowdoin and Council of Massachusetts Bay, Ticonderoga, March 25, 1777. The Life and Public Services Arthur St. Clair Soldier of the Revolutionary War; President of the Continental Congress; And Governor of the North-Western Territory – Correspondence and Other Papers Arranged and Annotated, William Henry Smith (Vol. 1, Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1882)

[31] Wayne to Schuyler, Ticonderoga March 23, 1777. The Life and Public Services Arthur St. Clair; T.W. Egly, jr., History of the First New York Regiment (Hampton, NH: Peter E. Randall, 1981), 60,121. Egly advises that Lt. Nathaniel Henry was wounded, not killed in this action as Adams’s account implies. This is substantiated by a regimental Return of March, 1779 listing his name. Henry’s widow’s pension deposition, W19761, says he was shot through the body. And, Hadden, A Journal Kept in Canada, 42fn, cites a report in the Continental Journal of April 10, 1777 that the attackers “fired a ball through the upper part of the breast of Capt. Heny, of which he is getting better.” The report also stated that the rebel party was composed of “thirty odd unarmed recruits with two officers”; See also New York in the Revolution as Colony and State, V.1, 17; the identity of the dead lieutenant has not been substantiated.

[32] Douglas Leighton, “Lorimier, Claude-Nicolas-Guillaume de,” DCB, V.6 (accessed January 1, 2017).

7 Comments

Thanks, Gavin, for a nice account of an example of “la petite guerre” that continually transpired in the area around Ticonderoga during the American occupation. Few folks are aware of such happenings. Few are also aware of the frequent French-Canadien involvement in activities on both sides of the conflict. This piece should help enlighten many.

Here’s another view of the incident. It comes from a letter dated Albany, March 29 that appeared in the “Continental Journal” on April 10:

“About a week ago the famous McCay (who broke out of Hartford Goal last September and made his escape) with a party of Indians attack’d thirty odd unarmed recruits with two officers, at Sabbath-day-point, a little before day, as they were asleep round a fire; they were on their way from Ticonderoga to Fort George to join their corps. They tomahawked four of the men on the spot and fired a ball through the upper part of the breast of Capt. Henry, of which he is getting better. Capt. Whitcomb with 40 men was dispatch’d as soon as the account reached Ticonderoga with a design to fall in with the enemy on their way to Canada, and I am just now informed he succeeded in his plan, and has killed several of the Indians and wounded several more: I hope it may be true. Only two of the party, beside the wounded officer, got clear of the Savages, the remainder that were not killed were taken prisoners.”

Note that it says the Americans were “unarmed.” I doubt the claim that nobody in the party carried arms but it’s possible some of them did not have weapons. If they had drawn theirs from the stores at Ti, they might well have had to return them when they received orders to move to Fort George since the garrison at Ti suffered from a shortage of arms.

Having done extensive research on Capt. Whitcomb and his rangers, I have found no reliable evidence that they fell in with McKay’s party.

I noticed the reference to James RankinS of the Tryon County rangers. Would that by Tryon County North Carolina? My maternal grandmother was a Rankin from that area of North Carolina as were other family members Cox, George, Harbison, Moffatt.

I see that there was a Tryon County New York during this period in history.

At the time, Tryon County was the largest county by land-mass in New York. Obviously named after it’s governor, William Tryon. Yup, same guy. When he left North Carolina (in 1771(?)), he moved north and took office there. The coolest thing about Tryon was that when the kerfuffle of revolutionary fervor heated up in NYC and before the British invasion in the summer of 1776, he took refuge in the British sloop-of-war Halifax in the harbor. He was left alone and still technically remained in office. I read somewhere (I think in “Under the Guns” by Bruce Bliven) that waiters would bring his meals to him via row boat.

I’m always pleased to see an article concerned with MacKay’s reconnaissance when one appears, not only because the subject has always been of special interest to me personally, but also because historians have typically paid it but little attention throughout the years though so many of the details regarding the expedition remain unclear or unanswered.

Perfect example, for instance, is the question as to whether the American party was armed or not as mentioned in Mike’s comment above. I found the transcription of a very interesting document online awhile back, attributed to Sergeant Joseph Graves (one of Captain Baldwin’s Rangers), dated March 19, 1777. The pertinent section of the account reads as follows:

“We cept [kept] no guard, neither had we our firearms loaded-only 3 of them, which were discharged at the enemy tho to no purpus, for there was nothing but powder in them.”

Based on Graves’ account, it would appear that Mike’s hunch was correct in that at least some members of the American party that morning were armed. Even more interesting, however, are the revelations that the guns they did possess were not even loaded and that guards which should have been in place around the camp for security had not been set. Anticipating no imminent dangers, the commanding officers neglected to enforce basic military protocol at a time requiring preparation for the unexpected with disastrous consequences for their commands.

On March 25, 1777 at Albany, Col. John Pierce Jr., paymaster general for the Northern Department, wrote to Col. Andrew Adams of Litchfield. Andrew is the brother of Samuel Adams, who Lorimier calls a loyalist living at Lake George:

“About three O’Clock in the Night of the 19th at Sabbath Day Point Instant a Party of one Captain, (Baldwin of the Rangers in this State) one Lieutenant (Henry of Van Schaicks Regt) and twenty three Privates were attacked by a number of Indians, with a white Man at their head, the Lieut.’ receivd. a Ball, which does not prove Mortal, and made his escape with four Men — the Captain and fifteen Privates are taken off by the Enemy, and four Privates are scalped and left Tomahawk’d in the Place — It seems some of these unfortunate Persons were returning from Ty — and some were going there — they met, at this place, designing to carry the night — they were ill provided with Arms & Ammunition — some were without Guns, while others having Guns had no Ammunition — thoughtless of Danger they had taken not the least precaution for their Security, were therefore surprised with the greatest ease —

In your text connected with footnote number 29 you refer to a “rebel militiman’s” journal entry. Jeduthan Baldwin was in fact a civilian engineer and not a militiaman. (And my 6th great uncle.)