Ten years in the planning and construction, the new fifty million dollar state of the art American Revolution Museum at Yorktown was officially dedicated in a thirteen day series of events celebrating each of the thirteen original states in the order in which they ratified our Constitution. From March 23 through April 4, 2017, daily programs celebrated each state with ceremonies, visits by state officials, re-enactors portraying appropriate state units, displays, demonstrations, and lectures that provided visitors with a rare opportunity to learn about the contributions of our ancestors to the winning of our independence.

As stirring and exciting as the celebratory programs were, the main attraction was and is the new museum itself. The American Revolution Museum at Yorktown replaces the Yorktown Victory Center, which opened in 1976 as a Virginia visitor center for the Bicentenial. It tells anew the story of the nation’s founding, from the twilight of the colonial period in the 1750s through the Revolutionary War to the dawn of the Constitution and beyond. Comprehensive indoor exhibits and outdoor living history areas capture the transformational nature and epic scale of the Revolution and its relevance to today.

INTRODUCTORY FILM

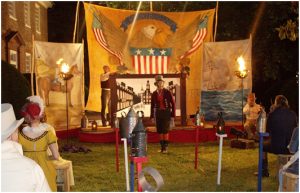

A visit to the museum starts with an introductory film ― “Liberty Fever” ― in the 170-seat museum theater. An early nineteenth century itinerant storyteller shares accounts of the Revolution, using a moving panorama or “crankie,” a form of mass media presentation popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in which dramatic backlit silhouettes scrolled on a long roll of paper in front of the audience.

Stationary silhouettes and moving shadow puppets scrolling by on the “crankie” are interwoven with live-action film segments telling the stories of five people who lived during the American Revolution. The film is intended to evoke emotional connections with the story and characters and encourage modern-day viewers to reflect on what the American Revolution means to their lives today, as well as to focus the visitor’s attention on the museum exhibits which they are about to see.

MUSEUM GALLERIES

The museums 22,000-square foot permanent exhibition gallery presents immersive environments featuring dioramas, interactive exhibits, short films and close to 500 period artifacts in five galleries designed to engage visitors in the story of the American Revolution, from its origins in the mid-1700s to the early years of the new United States.

The first gallery, The British Empire and America, examines the geography, demography, culture and economy of America prior to the Revolution and the impact of the Seven Years’ War, which ended in 1763 and resulted in expansion of Britain’s territory in North America. British Colonial America in 1763, an interactive map that displays colonial demographics, is the first of seven computer interactives located within the galleries. A coronation portrait of King George III from the studio of Allan Ramsay symbolizes British rule. A portrait of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, one of the two earliest known portraits done from life of an African who had been enslaved in the thirteen British colonies that became the United States, and a New York-made gorget with a silver bear symbol, probably used in diplomacy or trade with the Iroquois, show the complexity and diversity of colonial American society.

The next gallery, The Changing Relationship – Britain and North America, describes rising tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain as the British Parliament attempted to compel its North American colonies to help pay the costs of the French and Indian War and restrict colonial expansion onto the western lands that had been won from the French. Exhibits chronicle the causes of the growing rift, from the Stamp Act of 1765 to the First Continental Congress in 1774. Within a full-scale wharf setting – including a Red Lion Tavern that serves up a short film – issues of British economic control, taxation and representation are brought into focus. Among artifacts on exhibit are examples of American exports such as tobacco and pig iron, and English-made imports including scientific instruments, glassware, a set of silver teaspoons inscribed with symbols of liberty and a document box embossed with the gilded text “Stamp Act Rep ͩ/March 18, 1766.”

The largest gallery, Revolution, traces the war from both the military and the civilian perspective from the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775 to the American victory at Yorktown in 1781 and its aftermath. A rare July 1776 broadside of the Declaration of Independence, adopted more than a year after fighting began, is on display near a June 1776 Philadelphia printing of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, one of the inspirations for the U.S. Declaration.

Two early American victories – the 1775 Battle of Great Bridge, the first battle of the war pitting colonials against professional British soldiers to be fought in Virginia, and the 1777 Battle of Saratoga in New York, a turning point that led to a formal alliance with France – are highlighted in a diorama and a short film. A section devoted to the French Alliance of 1778 features a portrait of Benjamin Franklin painted in 1777 while Franklin was serving as an American representative in France, a portrait of Louis XVI painted during the king’s reign and a pair of Lafayette’s pistols.

As Britain scrambled to meet the worldwide threats posed by the entry of France into the war, the focus of military operations moved to the southern states. Here the visitor encounters a life-sized holographic display in which Daniel Morgan and Banastre Tarleton recount the Battle of Cowpens, each from his own perspective. Nearby is Battles of the Revolutionary War, an interactive panel on which visitors can look up and get summary information on more than 150 battles and skirmishes of the American Revolution. A little further along is the Battle Game which allows visitors, using a touch table, to command troops (and possibly change the outcome) of the battles of Cowpens, Camden and Kings Mountain.

The culmination of the war in the South was, of course, the siege of Yorktown. This momentous victory, which assured American independence, is recounted in a nine-minute film in an experiential “siege theater,” complete with rumbling seats, wind, smoke, and the smells of gunpowder, seawater and coffee which, in the words of one visitor, “will blow you away!” The action occurs on a 180-degree surround screen and includes the Battle of Capes, the attacks on British redoubts nine and ten, and the British surrender on October 19, 1781. Actors portray allied Generals Washington and Rochambeau and British General Cornwallis as well as Joseph Plumb Martin of the Continental Army’s Corps of Sappers and Miners, and Sarah Osborn, who followed the Continental Army with her husband and served food and coffee to the troops in the trenches. Artifacts from the Betsy, a British supply ship scuttled during the siege, on long-term loan from Virginia Department of Historic Resources, are displayed next to the theater.

The home front and the effect of the war on ordinary people is portrayed in three-dimensional settings that provide a backdrop for the stories of diverse Americans – Patriots and Loyalists, women and men, and enslaved and free African Americans. This section explores how the Revolution affected the lives of people like Mary Katherine Goddard, a printer whose January 1777 copy of the Declaration of Independence was the first to contain the typeset names of all the signatories, and Benjamin Banneker, a free African American who became famous in the 1790s as a scientist and writer. In Personal Stories of the Revolution, a life-size interactive exhibit featuring actors in period attire, visitors can hear the stories of twenty different people of the Revolution, and view images of artifacts connected to their lives.

Exiting the Siege Theater, visitors enter The New Nation gallery which takes the story of America forward from the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The difficult and often contentious evolution of the national government from the Articles of Confederation to the Constitution and the formation in 1789 of the national government that continues to today is recounted in exhibits and a short film. Nearby is a nineteenth century life-size statue of George Washington formerly exhibited at the U.S. Capitol, along with an assemblage of artifacts associated with the nation’s first president. A Wedgwood antislavery medallion and other artifacts speak to growing public opposition to slavery. An interactive display, U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, presents question-and-answer scenarios and a document explorer in which visitors can explore how the legacy of the Constitution and Bill of Rights applies to Americans today. The Liberty Tree invites contributions from both museum and online visitors of their thoughts on liberty which are displayed on lanterns hanging from its branches.

The final gallery, The American People, explores the emergence of a distinctive national identity following the Revolution, influenced by immigration, internal migration, and demographic, political and social changes. Emblematic of the new nation are an American-made sword whose silver pommel is in the form of an eagle and an early nineteenth century sandstone marker – carved with an eagle, stars and the word “Liberty” – from a ferry house that once stood along the Cumberland Road. An interactive map, The United States of America in 1791, which mirrors the interactive map British Colonial America in 1763, shows migration patterns and enables visitors to compare demographic and economic data between the thirteen American colonies of 1763 and thirteen United States of 1791. The exhibition concludes with a look at how the example of America has influenced the world.

OUTDOOR LIVING HISTORY INTERPRETIVE AREAS

As if the new permanent gallery exhibits were not enough, the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown features extensive outdoor living-history areas in which interpreters in period attire interact with visitors to add a personal dimension to their visit and to answer any questions they may have.

Located just outside the museum building is the Continental Army encampment. Representing two companies of American soldiers, the encampment includes rows of soldiers’ tents, an office tent for an adjutant, two captains’ quarters, and quarters for the regimental commander and major, laid out according to specifications in Baron von Steuben’s 1779 “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States.” Additional features of the camp include an earthen camp kitchen, a surgeon’s tent, and a quartermaster area, as well as makeshift dwellings representing shelter for female relatives of soldiers who followed the army and earned wages for performing domestic chores. Visitors can explore the camp tents, witness demonstrations of musket-firing and surgical and medical techniques, delve into the art of espionage and interact with interpreters to learn about the life of the soldier during the Revolutionary War.

The encampment also features a large drill field where visitors can participate in drill and tactical demonstrations, and a 250 seat amphitheater ― appearing as a redoubt on the outside and an artillery emplacement on the inside ― with an array of artillery pieces representing the types of guns in use at the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. Cannon firing demonstrations are scheduled several times a day during which visitors have an opportunity to learn hands-on how to operate an artillery piece.

Just beyond the encampment, the Revolution-era farm evokes the world of the eighteenth century family of Edward Moss (c.1757-c. 1786), whose life is well-documented in York County, Virginia, records. The story of Edward Moss and his family provides historical interpreters a frame of reference for talking about farm and domestic life during the American Revolution period.

Visitors first arrive at the farmhouse, a 34- by 16-foot structure with weatherboard siding, white oak roof shakes and a brick chimney on each end. The house has two first-floor rooms, a hall and parlor, each with paned-glass windows, and a second floor for storage and sleeping. Front and back doors open into the hall. Close by, a separate 20- by 16-foot kitchen has log walls with sliding shutter windows, a brick chimney, and wood clapboard eaves and roof. Dozens of varieties of vegetables and herbs are cultivated year-round in a nearby kitchen garden.

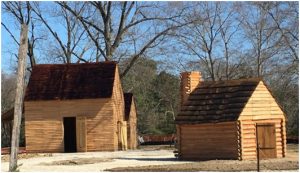

“Out buildings” include a 12- by 10-foot building representing quarters for enslaved people and a utility shed where historical interpreters demonstrate tools used for woodworking and processing raw flax and cotton into fiber for thread, and display examples of eighteenth century fabric dye. In a 20- by 16-foot tobacco barn, visitors can learn about the process of growing tobacco, from planting seeds to realizing a profit.

A fruit tree orchard and fields for growing wheat, corn, tobacco, flax and cotton – crops Edward Moss would have sold for cash and used for food, animal fodder and cloth production – complete the farm.

EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES

An important part of the museum is an educational center with five classrooms furnished with state of the art audio visual capabilities where trained museum educators share themed programs with school and other groups. For the general visitor, the museum offers daily presentations on various aspects of the history of the American Revolution.

The new American Revolution Museum at Yorktown, in this reviewer’s opinion, offers a not-to-be-missed opportunity for anyone with even a passing interest in the origins of our country to have both an enjoyable and an educational experience. There is something here for everyone from young families out to have a fun day to scholars with in-depth knowledge of the Revolution. Anyone planning a trip to the Historic Triangle area around Williamsburg, Virginia should make the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown a priority stop on their itinerary.

For more information, go to the Jamestown Yorktown Foundation’s web site at www.historyisfun.org.

2 Comments

This is an excellent review, Norman. As residents of Williamsburg, my family and I have spent many hours here, and I can assure you we will spend many more. To any visitor, your trip to the Historic Triangle will be grossly incomplete if you do not stop by the museum. Take a day (no, take two days) and explore this incredible treasure.

I just visited the “American Revolution Museum at Yorktown” last week, a little over a month past the grand opening celebration of March 23 – April 4, 2017. The above review by Norman Fuss is right on the money and accurate, so I’ll just give some other personal feelings I had from attending the museum.

I haven’t been to the Philadelphia “Museum of the American Revolution” (MoAR) which also opened to huge fanfare last month, so I have no means of comparison. But I think that worked to my advantage in my expectations.

I was immediately shocked and thrilled by the size and impact that the Yorktown museum had for me, sitting nearly on the banks of the James River with the flags of the thirteen colonies/states flying outside. Its entrance is open and very inviting.

Like Norman wrote, the layout of the museum is very well planned out with the well-produced film “Liberty Fever” initially introducing museum goers to the revolutionary era. The five distinct areas mentioned flow into one another seamlessly in subtle, spot-lit and attractive displays of artifacts of all types; with enough interactive components to also engage kids at every bend. One particular display that caught my strong attention was an exploded view of a working flint lock musket – showing the entire striking mechanism (very magnified) physically moving with each button pushed – at each step of the firing. For someone who had never fired a musket before, and had only seen (in movies) the pan flash before the ball fired, it was an interactive lesson even for an “older” guy like myself. I remember I hogged the display for a while.

The “Battle of the Capes” naval battle film took me by surprise of its 180 degree immersion of the viewer! I felt like ducking as cannonballs roared over my head as the battle raged all around me. Then it switched to the Yorktown siege… with the same total flinching involvement.

I’m skipping most of the exhibit halls because there’s just more in there than a simple review can cover. I might just add that the sensitive subject of slavery is addressed at various stages of the entire experience with candid, forthright statements.

Just outside the last display hall, the guests will find themselves within a Continental Army encampment complete with military drills and artillery firing watched from tiered seating that initially looks like a redoubt.

For the more mundane (and quiet-seeking) museum goers, there’s also a Revolution-era farm where there are “hands-on” opportunities for weeding and watering crops. Probably sounds like work to many young kids, who may also wonder what a “tobacco barn” was?

A 5,000-square-foot special exhibition gallery will open June 10, 2017 with an exhibition called “AfterWARd”, telling “the stories of four veterans of the Siege of Yorktown” and how, following the war, they went on to “shape the America we know today.”

Out of five stars, I have to give five stars to this new “American Revolution Museum at Yorktown” for sure.