Over the years, historians have written countless works on the military and political aspects of the Siege of Boston. Unfortunately, little attention has been given to the impact of the siege upon the residents of the city. As British military and political authorities attempted to recover from the disaster of April 19, 1775, the residents of Boston found themselves trapped inside a town that was on the verge of social and economic collapse.

On the evening of April 18, many of the residents knew a military operation was in motion and thus got little sleep. “I did not git to bed this night till after 12 o’clock, nor to sleep till long after that, & then my sleep was much broken, as it had been for many nights before.”[1] Many Bostonians were oblivious of plans to seize and destroy supplies located in Concord, Massachusetts. Instead, most believed the British objective was the arrest of Samuel Adams and John Hancock. As Sarah Winslow Deming recalled “the main was to take possession of the bodies of Mesrs Adams & Handock, whom they & we knew where were lodg’d. We had no doubt of the truth of all this.”[2]

Shortly after dawn, word of the fighting at Lexington reached Boston residents. Predictably, fear set into the populace. “Early on Wednesday the fatal 19th April, before I had quited my chamber, one after another came runing up to tell me that the kings troops had fired upon & killed 8 of our neighbors at Lexington in their way to Concord. All the intelligence of this day was dreadfull. Almost every countenance expressing anxiety & distress.”[3] As the day progressed, Boston broke into a state of panic. Many residents wandered about aimlessly, unsure of what the future held. In a letter to his son, the Rev. Andrew Elliot stated “I know not what to do, not where to go … poor Boston, May God sanctify our distresses which are greater than you can conceive – Such a Sabbath of melancholy and darkness I never knew … every face gathering paleness – all hurry & confusion – one going this way & another that – others not knowing where to go – What to do with our poor maid I cannot tell – in short after the melancholy exercises of the day – I am unable to write anything with propriety or connection … Everything distressing.”[4]

Over the next few days, as the American army surrounded the town and settled into a siege, scores of Bostonians discovered they were prohibited from fleeing the town. Gen. Thomas Gage was fearful that if the residents were permitted to leave, they would provide material assistance to the American army. As a result, he issued orders barring residents from leaving Boston. Boston resident Sarah Winslow Deming despaired “I was Genl Gage’s prisoner — all egress, & regress being cut off between the town & country. Here again description fails. No words can paint my distress.”[5]

According to merchant John Rowe, Boston’s economy immediately collapsed. Businesses stopped operating and fresh provisions for market stopped coming into town. “Boston is in the most distressed condition.”[6]

Residents gathered at a town meeting on April 22, 1775 to address their declining situation. A resolution was drafted to General Gage and highlighted the level of desperation they felt with the town being shut off to the outside world. “Inhabitants cannot be Supplied with provisions, fewell & other Necessarys of Life by which means the Sick & all Invalids must Suffer greatly, & Imediatly & the Inhabitants in general be distressed espesically Such which is by much the greatest party as have not had the means of laying in a Stock of provisions, but depend for daily Supplies from the Country for their daily Support & may be in danger of perishing unless the Communication be opened.”[7]

Representatives from the town also voted to approach General Gage to secure his permission for Americans to evacuate Boston. After a tense meeting, the general ultimately agreed to let the residents vacate to the countryside on the condition they surrender their weapons. Reluctantly the Bostonians agreed. A minister recalled the state of the civilian populace on the eve of the evacuation. “I not impelled by the unhappy Situation of this Town … all communication with the Country is cut off, & we wholly deprived of the necessaries of Life, & this principal mart of America is become a poor garrison Town … almost all are leaving their pleasant habitations & going they know not whither- The most are obliged to leave their furniture & effects of every kind … now I am by a cruel Necessity turned out of my House must leave my Books & all I possess, perhaps to be destroyed by a licentious Soldiery; my beloved Congregation dispersed, my dear Wife retreating to a distant part of the Country, my Children wandering not knowing whither to go, perhaps left to perish for Want, myself soon to leave this devoted Capital, happy if I can find some obscure Corner wch will afford me a bare Subsistence. I wish to God the authors of our Misery could be Witnesses of it. They must have Hearts harder than an adamant if they did not relent & pity us.”[8]

Those who chose to flee made their way to Boston Neck, the sole land route out of the town. At least four checkpoints along the neck were set up by the British army. Residents were searched for weapons and carriages and chaises were prohibited from leaving the city. Some residents pleaded with family and friends not to leave the “safety” of Boston.[9] Most pleas were rebuffed as many believed once British reinforcements arrived, the town would become a killing field.[10] This belief was only strengthened as rumors of atrocities being committed by soldiers inside Boston quickly spread.[11] Once again panic set in and residents pressed harder to get “out of ye city of destruction.”[12] At the height of confusion, British officials closed Boston Neck and the inhabitants were ordered back into the town.

On April 27, 1775, General Gage again reversed himself and gave permission for the remaining American residents to leave Boston.[13] Surprisingly however, British authorities undermined Gage and made it difficult, if not impossible, for Bostonians to leave. Passes were now required to cross over Boston Neck and their number was limited. “Near half the inhabitants have left the town already, & another quarter, at least, have been waiting for a week past with earnest expectation of geting Passes, which have been dealt out very Sparingly of late, not above two or three procur’d of a day, & those with the greatest difficulty. its a fortnight yesterday Since the communication between the town & country was Stop’d, of concequence our eyes have not been bless’d with either vegetables or fresh provisions, how long we Shall continue in this wretched State.”[14] On May 5, a large number of passes were issued and many residents quickly left via Boston Neck. “You’ll see parents that are lucky enough to procure papers, with bundles in one hand and a string of children in the other wandering out of the town (with only a sufferance of one day’s permission) not knowing whither they’ll go.”[15] The following day General Gage inexplicably revoked all outstanding passes again, declared no more were to be issued and those who wished to leave were prohibited from doing so.[16]

By the end of May, Boston more closely resembled a post-apocalyptic world than a bustling seaport community. While many had abandoned the town, others barricaded themselves inside their homes and had private guards watching over their property. The Reverend Eliot accurately described the state of Boston on the eve of the Battle of Bunker Hill: “I have remained in this Town much ag: my inclination … Most of the Ministers being gone I have been prevailed with to officiate to those who are still left to tarry … Much the greater parts of the inhabitants gone out of the town … Grass growing in the public walks & streets of this once populous & flourishing place – Shops & warehouses shut up – business at an end every one in anxiety & distress.”[17] Fresh provisions were increasingly scarce and trapped occupants were often forced to survive on food of questionable quality. “Its hard to Stay coop’d up here & feed upon Salt provissions … We have now & then a carcase offerd for Sale in the market, which formerly we would no thave pickd up in the Street, but bad as it is, it readily Sells.”[18]

The combination of British troops, Loyalist refugees and Boston residents all occupying a small amount of space only exacerbated a very dangerous situation. Press gangs roamed the town looking for civilian men to force into manual labor.[19] Inhabitants were arrested for merely being suspected of espionage or providing aid to the enemy.[20] Many of the soldiers and camp followers abused the inhabitants, stole from them and plundered their property, particularly that of residents who had left the city. John Andrews complained that the “Soldiery think they have a license to plunder evry ones house & Store who leaves the town, of which they have given convincing proofs already.”[21] According to John Leach, Boston had devolved into a complicated “scene of oaths, curses, debauchery, and the most horrid plasphemy committed by the provost martial, his deputy and Soldiers who were our guard, Soldier prisoners, and Sundry Soldier women.”[22]

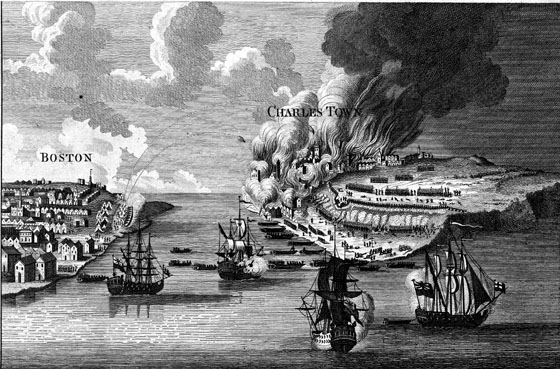

Nor were Loyalist refugees immune from the hardships of the siege. Dorothea Gamsby was ten years old when the war broke out. In a letter written years later to her granddaughter, Gamsby accurately described how tenuous the situation inside Boston had become by the eve of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Residents continued to hide in fear and were under constant stress. Most believed that the town would be invaded by the rebels and its inhabitants slaughtered at any moment. As Gamsby recalled the Battle of Bunker Hill, “then came a night when there was bastle, anxiety, and watching. Aunt and her maid, walked from room to room sometimes weeping. I crept after them trying to understand the cause of their uneasiness, full of curiosity, and unable to sleep when everybody seemed wide awake, and the streets full of people. It was scarcely daylight when the booming of the cannon on board the ships in the harbour shook every house in the city … My aunt fainted. Poor Abby looked on like one distracted. I screamed with all my might.”[23]

As the siege progressed, conditions inside the town continued to decline. Some houses of worship were demolished for fuel or converted into riding stables. Disease and sickness began to spread inside Boston.[24] As Timothy Newell noted, there were “several thousand inhabitants in town who are suffering the want of Bread and every necessary of life.”[25] The end result was a general sense of despair throughout the surviving civilian population. Some of the common emotional descriptions by residents during the siege include such negative words as “anxiety,” “distress,” “forsaken” and “darkness.” Some accounts even expressed what only could only be interpreted as hopelessness or borderline suicidal thoughts. “It is impossible to describe the Distress of this Unfortunate Town … I try to do what Business I can but am Disappointed & nothing but Cruelty and Ingratitude falls to my lot.”[26]

A final humiliating blow to the occupants came on the eve of the British evacuation of Boston. British troops and Loyalist refugees roamed the streets plundering homes, warehouses and businesses of the local populace. According to merchant John Rowe, “They stole many things and plundered my store … I remained all day in the store but could not hinder their Destruction …they are making the utmost speed to get away & carrying … everything they can away, taking all things they meet with, never asking who is Owner or whose property – making havoc in every house & destruction of of all kinds.”[27] By March 17, 1776, British soldiers were suspected of committing acts of arson in the northern part of town. Troops repeatedly threatened, robbed and intimidated the inhabitants. To the horror of many Bostonians, even officers participated in the illegal activities.[28] The army did not turn a totally blind eye to these crimes; during the siege and in the two months following the evacuation, at least twenty-seven military personnel, including two officers and three followers, were tried by general courts martial for crimes against inhabitants, primarily robbery and plunder.[29] Others may have been tried by lesser courts, but in spite of efforts, crimes by the soldiery were widespread.

Following the British and Loyalist evacuation of Boston, American troops entered the town and were joyfully greeted as liberators. “Thus was this unhappy distressed town … relieved from a set of men, whose unparalleled wickedness, profanity, debauchery and cruelty is inexpressible.”[30] For the next several years, Loyalist and “Patriot” inhabitants of Boston petitioned the Continental Congress and the Massachusetts government for compensation for property lost or damaged as result of the siege.[31] Some claims were paid, others were ignored or denied. In the weeks after the conclusion of the siege, American troops moved south to New York City. Never again in Boston’s history were residents subjected to the horrors of a military siege or occupation.

[1] Sarah Winslow Deming Journal, Page 3, Historic Winslow House Association, Marshfield, Massachusetts.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Reverend Andrew Eliot to His Son, April 23, 1775, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[5] Deming Journal, Page 4.

[6] Letters and Journal of John Rowe, Merchant, April 21, 1775, Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

[7] Minutes from the Town of Boston, April 22, 1775, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[8] Andrew Eliot to Thomas B. Hollis, April 25, 1775, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[9] Deming Journal, Page 4.

[10] Ibid. “I had been told that Boston would be an Aceldama as soon as the fresh troops arriv’d, which Mr. Barron had told me were expected every minute.” Ibid.

[11] Ibid. “I saw, & spoke with several fri[ends] near as unhappy as myself … while we were waiting … there was a constant coming & going; each hinder’d ye other; some new piece of soldiary barbarity, that had been perpetrated the day before, was in quick succession brought in.” Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] At the same time, Loyalist refugees trapped behind American lines were permitted to enter the town.

[14] John Andrews to William Barrell, May 6, 1775, Papers of Andrew Eliot, 1718-1778, Harvard University Archives, Harvard University.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid. “You must know that no person who leaves the town is allow’d to return again & this morng an order from the Govr has put a stop to any more passes at any rate not even to admit those to go, who have procurd ‘em already.” Ibid. In a letter to her husband, Abigail Adams chastised Gage and other British officials for the continuous issuing and revoking of passes and the resulting stress to the Americans trapped inside the town. Abigail Adams to John Adams, May 7, 1775, Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[17] Draft letter from A. Eliot to Unknown Recipient, May 31, 1775, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[18] Andrews to Barrell. “Was it not for a triffle of Salt provissions that we have, twould be impossible for us to live, Pork & beans one day, & beans & pork another & fish when we can catch it, am necessitated to Submit to Such living or risque the little all I have in the world.” Ibid.

[19] “Press-Gangs parading the Streets in quest of Labourers … likewise several Persons taken up and imprisoned upon Suspicion. The usual Consequences of martial Law” William Cheever Diary, June 19, 1775, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[20] “Yesterday Mr. James Lovell and John Leach with others were imprisoned by martial Authority.” Ibid, July 1, 1775. “Martial Law has had a full Swing for this month past. The Provost with his Band entering houses at his pleasure, stoping Gentlemen from enter:g their Warehouses and puting some under Guard: as also pulling down Fences, etc., particularly Mr. Carnes’s Rope Walk and our Pasture.” Ibid, July 21, 1775.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Diary of John Leach, From July 1st to July 17th, 1775,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Vol. XIX (1865), 255-263.

[23] Dorothea Gamsby Manuscript, Chapter 5, private collection.

[24] “Social life is almost at the last gasp. We have passed favorably through the smallpox.” “Letter of Isaac Winslow,” January 15, 1776, The New England Genealogical Register, Vol. LVI (1902), 48-54.

[25] “Journal of Timothy Newell,” October 10, 1775, Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Series 4, Vol. I (1852), 261-276.

[26] Letters and Journal of John Rowe, March 7 and 8, 1776.

[27] Ibid, March 11, 1776. Rowe later noted “There was never such Destruction and Outrage committed any day before this … the inhabitants are greatly terrified & alarmed for Fear of Greater Evils.” Ibid, March 11 and 12, 1776.

[28] Ibid, March 13 – 17, 1776.

[29] Proceedings of these trials are in the Judge Advocate Papers, WO 71, British National Archives.

[30] Journal of Timothy Newell, March 17, 1776.

[31] For an example of a Loyalist petition for compensation, see William Jackson to the Continental Congress, July 6, 1776, Miscellaneous Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

4 Comments

An excellent article. For a fictional account of the siege from a loyalist perspective, it’s hard to beat Kenneth Roberts’ OLIVER WISWELL.

Ditto. Excellent article. “What to do with our poor maid I cannot tell” ( ! )

Lawbreaking by British soldiers was bad enough that some were sentenced to death by winter of 1775-76.

“Robberies, and housebreaking in particular, had got to such a height in this town, that some examples had become necessary to suppress it. Two soldiers, late of the Fifty-Ninth Regiment of Foot, have been tried, convicted, and sentenced to suffer death, for breaking into and robbing the store-house of Nathaniel and William Coffin; one of them has suffered; the other, Thomas Owen, as a young offender, and having other circumstances to plead in his favour, I have thought proper to reprieve.”

(Gen Howe, Jan 22, 1776)

Thank you for one of the most descriptive articles about life in Boston under British control. This is a vivid account of a town under siege. I can almost picture myself among those desperate residents: “There was never such Destruction and Outrage committed any day before this … the inhabitants are greatly terrified & alarmed for Fear of Greater Evils.”