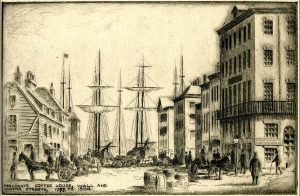

In 1779, three years into the British occupation of New York during the American Revolution, a man returned to the city to “attend the usual hours of business at [Merchants’] Coffee House.”[1] He must have been destined to pursue his particular trade, for his name was “William Tongue, Licensed Auctioneer.”[2] The institution to which the rather aptly named Mr. Tongue returned was already well established as the economic center of Revolutionary New York, but despite its fame as a mercantile hub, the coffee-house was far more than a mere auction block. In 1775, nine months before the Declaration of Independence, when British naval superiority was severely weakening American trade in Patriot-held New York, a citizen signing only as “A Friend to the City” made a public call for customers by espousing the societal value of a place like the coffee-house.[3] When the auction business exploded following British occupation and a resurgence of trade, but public meetings had declined due to the association of such assemblies with fomenting rebellion, the Loyalist proprietor of Merchants’ published a promise to once again make the establishment a place of social gathering.[4] Whether the merchants themselves were profiting or not, Merchants’ thrived because it was also regarded as the city’s preeminent social node, a reputation the proprietors of the coffee-house worked keenly to establish and maintain.

The coffee-house culture of Europe has been researched in detail,[5] but its American counterpart has received less attention.[6] The colonial American coffee-houses, the focus here being those in New York in the years surrounding British occupation between 1776 and 1783, were more like their European predecessors than the historiography often recognizes. Colonial coffee-houses like Merchants’ descended from the coffee-houses of Europe, which were unquestionably social places at their core. Joseph Monteyne surmised of the London coffee-houses: “Gentry, tradesmen, and others are all welcome here.”[7] The space Menteyne described is one that served a multiplicity of functions. Referencing The Character of a Coffee-House from 1673, he concluded: “Indeed, in this pamphlet [the coffee house] shifts rapidly from looking like a church with its low whispering and candlelight, to a music room, to a gaming house because of its long tables, and then ‘on a sudden it turns Exchange, or a Warehouse for all sorts of Commodities.’”[8] The colonial New York coffee house served the same variety of purposes. As Monteyne asserted, “coffee-houses are now routinely cited as the place in which to locate the beginnings of polite society and the origins of a public sphere.”[9] The coffee-house of New York was this space in the late eighteenth century. The wide range of people that it drew in through its auctions created a public sphere that was largely classless, just like the coffee-houses of London which it so fervently mimicked.[10]

Throughout the Revolutionary era, Merchants’ Coffee-House, the most influential and usually the only coffee-house in colonial New York, was the city’s established mercantile center, but its reputation as a social centre was less secure. In 1788, Jean Pierre Brissot de Warville wrote: “There is no coffee-house at Boston, New York, or Philadelphia. One house in each town, that they call by that name, serves as an exchange.”[11] Despite de Warville’s opinion that colonial coffee-houses didn’t serve the same social purpose as proper coffee-houses, the owners of Merchants’, both Loyalist and Patriot, worked tirelessly to establish and maintain it as the social center of the city.

The 1775 editorial in the New York Journal by “A Friend to the City” lamented the waning patronage of the coffee-house and hotly proposed making it great again. It read in part: “It gives me concern, in this time of public difficulty and danger, to find we have in this city, no place of daily general meeting, where we might hear and communicate intelligence from every quarter and freely confer with one another, on every matter that concerns us.”[12] The author confirmed bluntly, “Coffee Houses have been universally deemed the most convenient places of resort, because at a small expence of time or money, persons wanted may be found and spoke with, appointments may be made, the current news heard, and whatever it most concerns us to know.”[13] While the anonymous author made a strong case for the usefulness of coffee-houses, their main concern seems to have been with that small expense they so casually dismissed. The author continued in the same editorial, “I have observed with surprise, that but a small part of those who do frequent [the coffee-house], contribute any thing at all to the expence of it, but come in and go out without calling for, or paying any thing to the house.”[14] Though the coffee-house was recognized as the city’s mercantile center, its lifeblood was its paying customers.

Still, both prior to and during occupation, the coffee-house remained largely the haunt of merchants and the place of auctions. The New York Journal records of Merchants’ in 1772, that it “is now fitted up in a most neat and commodious manner for the reception of Merchants and other Gentlemen.”[15] These were not the only types the proprietors of Merchants’ hoped to attract, however, and thanks to the nearly constant auctions, the coffee-house was often awash with spendthrifts of all stripes. The public nature of the coffee house forced interaction between classes, for on the same day such a wide range of goods might be auctioned off as “Broad Cloths, Coatings, Flannels… 100 Tierces of New Rice … [and] The Brigantine La Susanne.”[16] Chief among the merchandise being sold was property, such as the five houses and lots sold in Ann’s-street in 1770,[17] but many other things changed hands at the coffee-house as well. In 1772, for instance, were auctioned: “The 6 carriage guns, 4 pounders (that were advertized last week) now lying at the blacksmiths shop on Cruger’s wharf.”[18] Two weeks later were auctioned: “Five or six hogsheads of excellent Muscovado sugars.”[19] Being the center of a variety of mercantile enterprises, however, did not always translate into profit for the proprietor. Larger goods were often sold just outside of the coffee-house itself[20] and the owner might not see a single person present for the auction buy a cup of coffee. To profit with consistency, the institution had to be more than simply an auction house.

And Merchants’ Coffee-House was certainly much more than just an auction house. Run by Mary Ferrari until 1776, when it was taken over by the staunch patriot Cornelius Bradford, by the American Revolution the coffee-house had made significant inroads toward becoming the social center of the city.[21] In the years preceding the Revolution, the space was a hotbed of Patriot sentiment. In 1774, a notice was printed which read: “The Public are hereby requested to attend at the Coffee-House, on Tuesday next at XII o’Clock to signify their Sense of the Resolves entered into by the Committee of Correspondence.”[22] Merchants’ association with the revolution is further evidenced by the situation of Thomas C. Williams, who was rumoured to have been “the shipper and part owner of the tea lately destroyed at Annapolis.”[23] Williams denied any involvement with the tea, and was “advised that if such was really the case, a narrative of it drawn up, sworn to, and put up at the Coffee-House, would effectually remove the people’s resentment against him.”[24] The coffee-house was both the place where rebellion was discussed and the place from which Patriot sentiment emanated. These kinds of gatherings were perfect for Ferrari and Bradford as they both served a social function, and packed the place at a time when trade was faltering before British superiority at sea. Bradford’s success, however, would be short lived. In 1776, about eight months before the British took control of the city, a notice was printed which read, “The Freemen, Freeholders, and Inhabitants of the City of New-York, are desired to meet at the Coffee-House, on Saturday the 3d instant, at 12 o’Clock in the Forenoon, to choose a Committee to act for them.”[25] Before the year was out, many of these inhabitants, Bradford among them, would be forced to flee the city before the troops of Gen. Sir William Howe.

Unlike its proprietor, it seems that Merchants’ Coffee-House as an institution welcomed the British with open arms. The owner at this time is hard to ascertain. According to John Austin Stevens, the Chamber of Commerce, suspended since 1775, resumed in the coffee-house’s upper room in 1779, paying rent to the landlady, one Mrs. Smith.[26] In 1781, James Strachan, the proprietor of the popular Queen’s Head Tavern, took over Merchants’ at a time when the coffee-house was firmly solidified as the mercantile center of the city, but when its position as a social center was on the wane. The sudden economic explosion that accompanied British occupation and trade left little room for the place to be used as a meeting hall. The coffee-house had always been best known as an auction house, and during occupation it was a vibrant one, often to the detriment of its other social functions.

Even when times were economically good, as they were during the British occupation, the proprietor still relied on his customers for his profit and took pains to depict his establishment as a social necessity. James Strachan wrote of his move to the famous coffee-house, “he intends to pay attention not only as a Coffee House, but as a Tavern in the truest sense; and to distinguish the same as the City Tavern and Coffee House. With constant and best attendance.”[27] This reference to the City Tavern in Philadelphia was a promise. Francois Furstenberg wrote of that tavern, “If Philadelphia’s elite community had a hub by which travelers, goods, information, and capital circulated, this was it.”[28] The pledge was that Merchants’ would soon be unrivaled as the social center of the city, just as the City Tavern was in the new nation’s capital. Strachan too was careful to portray his coffee-house as a place open to all. Even at a time when Merchants’ Coffee-House was a mercantile powerhouse, the proprietor of the establishment needed it to be a recognized social center, as his hopeful reference to “constant and best attendance”[29] attests.

As the advertisements show, Merchants’ was unquestionably the primary auction block of occupied New York.[30] The coffee-house also began to auction an even greater variety of goods than it had before. The most striking addition is the wildly increased number of ships up for sale. Merchants’ became the principle place where vessels taken as prizes around the area were sold.[31] The sloops Pennsylvania Farmer and Ranger, and the brigantine La Susanne are just some of the many ships advertised as being sold at the coffee-house.[32] Unlike these large investments, however, much of the merchandise being hocked was small and affordable. The same advertisement that offered the Pennsylvania Farmer, also offered “100 Hogsheads TOBACCO, A considerable Part of which, is of the bright yellow kind called Kytefoot.”[33] Another advertised “A quantity of Household Furniture consisting of Tables, Chairs, Beds, Bedding … [and] the cargo of the prize sloop Nonsuch, consisting of Indian Corn, and Bar Iron.”[34] Yet another advertisement offered for sale “a likely negro Woman, about 23 Years old, with her female Child about 3 Years old, capable of all sorts of House Work, sold for no Fault, but the Owner going to Europe with the first Opportunity.”[35] Again, these auctions brought in citizens from across the classes, but as before, many were held just outside the coffee-house, leaving the proprietor with little or no profit. To make matters worse, this time there were no political gatherings to fall back on.

The fact that it had been the principle meeting place of the New Yorkers who most fervently fomented rebellion could hardly have been missed by the British and Loyalists. This seems to have affected patronage in the years of occupation. Between 1776 and 1783, the only gatherings advertised in the papers as being held at the coffee-house are small meetings between individual creditors and debtors.[36] As they were before the revolution, many assemblies were advertised as being held at the city’s many taverns, but these meetings were rarely political. For example, the Queen’s Head Tavern of James Strachan (prior to his move to Merchants’) saw “A Meeting of the Refugees from the Colony of Virginia,”[37] and “the Quarterly Meeting of the Scots Friendly Society.”[38] One of the few gatherings with something of a political, if also piratical, character was advertised in the Royal Gazette: “A Meeting of the Gentlemen interested in fitting out private ships of war from this port, is desired at Loosely and Elms’s Tavern.”[39] Though auctions undoubtedly brought in some business for Strachan, his establishment was not being used to its social potential. The laymen were meeting in taverns and increasingly the gentlemen were flocking to a different coffeepot.

In its more than fifty year history, Merchants’ rarely had much competition, but during the occupation a rival appeared on its doorstep. James Rivington, the Loyalist printer of the Royal Gazette, opened a private coffee-house next to his print shop only a few blocks from Merchants’ and it soon began to attract many of the old coffee-house’s most important customers. Alexander Rose quoted Henry Wansey’s account: “During the time the British kept possession of New York, [Rivington] printed a newspaper for them, and opened a kind of coffee-house for the officers; his house was a place of great resort; he made a great deal of money during that period.”[40] This was essentially money taken out of Strachan’s pocket. Perhaps that is why he took pains to alert the public that “he intends to pay attention not only as a Coffee House, but as a Tavern in the truest sense.”[41] With the elite customer base apparently eroding, Strachan needed patrons. Like Bradford before him, he turned to the institution’s reputation as a social center, open to all.

As it was, Strachan’s time at the helm of Merchants’ was also short-lived. Following the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British left New York and Cornelius Bradford returned to take back proprietorship of the coffee-house.[42] He wasted little time in returning the establishment to its former social glory, and surprisingly he did so without losing much ground on the mercantile side of affairs. In many ways, it was at this time that Merchants’ peaked. It was a trade powerhouse and a social powerhouse; a coffee-house in every sense of the word.

The advertisements for auctions following the British evacuation are marked by both the pre-occupation and occupation eras. As before the Revolution, land was once again a prime commodity, like the “Lease of Seven Lots of Land”[43] sold by James Hughes in 1786. Occupation left its mark as well, however. Prize and other ships appeared much more frequently than they had pre-revolution, like “The Ketch Sea Dog, now laying opposite Mr. William Remsen’s store,”[44] sold in 1785. Luxury items also varied much more than they had prior to the rebellion. For example, in 1784 were sold “Thirteen hogsheads Claret, A few cases of Anchovies, Two hogsheads Taunton Ale in bottles, One hundred Portmantau.”[45] As it had been throughout occupation, the coffee-house was the primary auction block, attracting everyone out for a deal, regardless of affluence or social standing. Unlike during occupation, however, auctions were not the only gatherings that drew people through its doors.

In the wake of Bradford’s return, the coffee-house resurged as a social and political center, thanks largely to his own efforts. In 1783 he published a notice to inform “All Masters of Vessels … that the Subscriber who keeps the New-York Coffee-House, has prepared a book in which he will insert the names of such as may please to call on him … in order that the Gentlemen of this city, or travelers may obtain the earliest intelligence thereof.”[46] Ukers surmised that Bradford made “the first attempt at a city directory”[47] around this time as well. Merchants’ also saw the return of its meetings. The Whig Society met there in 1784 with “The Vice President, And forty-three Members.”[48] Many other groups made use of the establishment as well. An advertisement appeared in 1785 that read: “The New-York Society for promoting useful knowledge, will meet this evening, at six o’clock at the Coffee-house, according to the constitution.”[49] An anonymous author had complained in 1775 that New York had “no place of daily general meeting.”[50] By his death in 1786, Bradford had shown the city that, in fact, it had a very good one.

The coffee-house to which William Tongue returned in 1779 was very different from the one he likely worked at before the Revolution. It had become an even mightier mercantile powerhouse, but it had lost some of its social standing. If Mr. Tongue stayed on following the British abandonment of the city in 1783, he witnessed the famous old institution return to its place of prominence at the centre of the city’s social life. Because of the wide variety of people drawn to the auctions at the coffee-house, the location was perfect for a social node. The proprietors of Merchants’ understood the potential the coffee-house represented, and by keenly publicizing the social importance of their establishment, they created exactly the kind of place that Jean Pierre Brissot de Warville believed New York was lacking. Though de Warville never understood the social value of Merchants’ Coffee-House, its proprietors did, and thanks to their efforts, editorials, and advertisements, so too did the citizens of colonial New York.

[1] Royal Gazette, September 27, 1779.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “To the Inhabitants of New York,” New York Journal, October 19, 1775.

[4] New York Gazette, April 30, 1781.

[5] Brian William Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffee-House (New Jersey: Yale University Press, 2005); Markman Ellis, Eighteenth-Century Coffee-House Culture: The Eighteenth-Century Satire (Pickering & Chatto, 2006); Mary R. M. Goodwin, The Coffeehouse of the 17th and 18th Centuries (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1990).

[6] John Austin Stevens, “Old New York Coffee-Houses,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 64 (1882), 481-499; William H. Ukers, All About Coffee (New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, 1922).

[7] Joseph Monteyne, The Printed Image in Early Modern London: Urban Space, Visual Representation, and Social Exchange (New York, Ashgate, 2007), 34.

[8] Ibid., 37.

[9] Ibid., 38.

[10] New York Gazette, April 30, 1781. The Loyalist proprietor of Merchants’ at the time, James Strachan, offered “Tea, Coffee, &c., in the afternoons as in England.” He also offered the other “Soups and Relishes” customary of British coffee-houses.

[11] Albert Bushnell Hart, ed., American History Told by Contemporaries: National Expansion, 1783-1845 (Honolulu, University Press of the Pacific, 2002), 33.

[12] “To the Inhabitants of New York,” New York Journal, October 19, 1775. At this time, Mrs. Mary Ferrari was serving as the landlady and proprietor of Merchants’ and it is possible that she signed this editorial “A Friend to the City” so as to obscure the fact that it was written by a woman. It is also possible, of course, that it was written by someone with no direct connection to Merchants’. The obvious goal of reviving the coffee-house, however, makes it seem likely that this editorial was written by someone who was at least associated with the institution.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] New York Journal, May 7, 1772.

[16] “Public Auction,” Royal Gazette, September 29, 1779.

[17] “To be sold, at public Vendue,” New York Journal, November 10, 1770; “To be sold at Publick Vendue,” New York Journal, February 27, 1773.

[18] “Public Auction,” New York Gazette, March 2, 1772.

[19] New York Gazette, March 16, 1772.

[20] New York Journal, May 2, 1771.

[21] Stevens, “Old New York Coffee-Houses,” 481-499.

[22] Isaac Low, Committee chamber, July 13, 1774 (New York, John Holt, 1774).

[23] New York Journal, November 2, 1774.

[24] Ibid. Williams never posted the notice, and is described in the same editorial as having fled town.

[25] The Freemen, freeholders, and inhabitants of the City of New-York, are desired to meet at the Coffee-House (New York, 1776).

[26] Stevens, “Old New York Coffee-Houses,” 496. The proprietor of the coffee-house between late 1776 and 1779 still does not seem to be known.

[27] New York Gazette, April 30, 1781.

[28] Francois Furstenberg, When the United States Spoke French: Five Refugees Who Shaped a Nation (New York, Penguin Press, 2014), 90.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Royal Gazette, November 19, 1778. For example, of the seventeen advertisements that appear on one page in this paper, eight are for auctions at Merchants’, three are for auctions at the wharf below the Coffee-House, two are for auctions at competing houses, three are for private sales, and one is for a lost pocketbook.

[31] Ukers, All About Coffee, 120.

[32] Royal Gazette, May 30, 1778; “Public Auction,” Royal Gazette, September 29, 1779.

[33] Ibid.

[34] “Public Auction,” Royal Gazette, February 27, 1782.

[35] “Public Auction,” Royal Gazette, April 13, 1782.

[36] Royal Gazette, October 25, 1783. For example, “The Creditors of William Gerard, of the City of New-York, Grocer, are requested to meet at the Coffee-House on Tuesday next.”

[37] Royal Gazette, December 8, 1779.

[38] Royal Gazette, February 26, 1780.

[39] “Private Ships of War,” Royal Gazette, August 29, 1778.

[40] Alexander Rose, Washington’s Spies (New York: Bantam, 2006), 318.

[41] New York Gazette, April 30, 1781.

[42] Ukers, All About Coffee, 120.

[43] James Hughes, To be sold, on Monday the 19th day of June instant, at public vendue, at the Merchants Coffee-House. New York: Printed by Francis Childs, 1786.

[44] New York Packet, March 7, 1785.

[45] Independent Journal, September 9, 1784

[46] Cornelius Bradford, New-York Coffee-House. New York: publisher not identified, 1783.

[47] Ukers, All About Coffee, 120.

[48] Lewis Morris, At a meeting of the Whig Society. New York: publisher not identified, 1784.

[49] New York Journal, December 14, 1786.

[50] “To the Inhabitants of New York,” New York Journal, October 19, 1775.

7 Comments

Jonathan, thanks for an interesting article on an aspect of cultural history of the period. As I enjoy connecting spying to everyday activities, I wanted to mention that Rivington’s coffee house was a joint venture with Robert Townsend, Culper, Jr., of the American Culper Spy Ring in New York City, and served to provide Townsend with a venue where he could overhear British officials and officers discuss, in a peer setting, information of intelligence interest. Rivington, of course, turned out to be an American spy as well, but details are lacking on exactly when.

See “Spies, Patriots, and Traitors” p. 178.

Thanks for the reply! It certainly seems Rivington and Townsend understood the value of the coffee-house as a social network and the value of tapping into that network, for whatever reason. Also in terms of espionage, the New York coffee-houses were attacked by several Patriot newspapers as being the source of the counterfeit Continental Currency that appeared during the Revolution, and the Loyalist-leaning New York Gazette actually published a propagandized advertisement offering counterfeits for sale at the coffee-house between 11pm and 4am. It was also rumoured that the counterfeits were being printed on Rivington’s press on board the HMS Phoenix in New York Harbour, further complicating that question of Rivington’s loyalties and how and when they shifted.

Do we know the actual location of the Rivington Coffee House in New York City ? Thanks the article was great… Tom

In “The Original American Spies, Seven Covert Agents of the Revolutionary War” Paul R. Misencik created a map (p. 103), which places the coffeehouse on the NW corner of Wall & Queen (modern Pearl) Sts. across from the Rivington Print shop on the NE corner.

David Conroy’s “In Public Houses,” about the taverns of eighteenth-century Massachusetts, surprised me by showing that Boston’s “coffee houses” paid more in alcohol excise taxes than any other establishment. The term “coffee house” in Boston might just have meant “upscale bar,” and the atmosphere might have been much inebriated as caffeinated.

A great article. Helpful for understanding coffee house culture in Loyalist Saint John. interesting also to note that Saint John’s Scots Friendly Society was a carry-over from Loyalist New York city.

I really enjoyed this article…extremely insightful.

I own a Mexican 2 reales coin from the late 18th century that was countermarked (stamped) with ‘Cooper’s Coffee Room – 103 Nassau Street’ in New York. This was a common way for merchants to advertise in the 18th and 19th centuries. They would punch their business information into a circulating coin.

I’ve not been able to find out anything at all about that business in all of my internet searching. Any chance you can help me dig up some information from Cooper’s Coffee Room on Nassau Street, or otherwise give me some tips on how I could learn more about it? thanks again