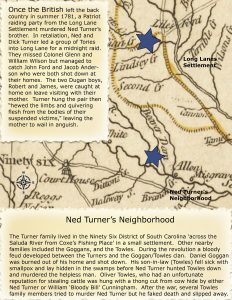

Deep in South Carolina’s back country the Loyalist world came apart in the fall of 1781. British occupation ended with their retreat into the Charleston area and proclamations concerning safety of the loyalist families had been largely ignored by local Patriots. Vengeance and plunder were the priorities for far too many. The time of oppression had come to an end and the Tories no longer held the upper hand. However, that situation changed briefly in early November as several bands of Loyalist raiders rode into the old Ninety Six District seeking to stop the violence against their friends and families. Most modern historians lump these raids into a single group known as the “Bloody Scout” which was led by William “Bloody Bill” Cunningham. In truth, Cunningham did not act alone. Once in the back country, his Loyalists spread out into small groups intent on murder and private violence. Among the more notorious members of the Scout was a Loyalist from the Ninety Six District named Ned Turner.[1] Folks from that part of South Carolina still maintain stories from his terrible time in a sourcebook known as The Annals of Newberry.

The Turner family emigrated to the back country in 1751 with the founding of Turner’s Settlement close to the conjunction of the Saluda and Little Rivers. William Turner built a small fort (known locally as a “station”) that consisted of blockhouse and stockade. When the Cherokee War broke out ten years later he managed to save his family and many of the neighbors by closing up the gates and holding out while the Indians fired helplessly from outside the walls. William’s wife, Mary Turner, had relatives living nearby in the settlement. They were well known and respected in the area and raised at least five children including the subject here, Ned Turner.

Ned Turner vs. the Dugans

While British control was falling apart, a group of Patriots raided the Turner home and killed Ned’s brother. These Patriots had been led by Col. David Glenn[2] of the Long Lane Settlement which was along the south side of the Enoree River.[3] Naturally this did not set well with Ned and his other brother, Dick Turner. After the battle of Eutaw Springs, many of the back country militia remained with Gen. Nathanael Greene in his camp near the Santee. This meant their homes were vulnerable, defended by only a few men left behind on leave, many of whom were hampered by illness or injury. Ned Turner joined with Bloody Bill Cunningham’s raiders with a plan to take advantage of the situation.

At some point during Cunningham’s Scout,[4] Turner broke off from the main group and formed his own band. His first stop was the home of the Dugan family in the Ninety Six District. Capt. Robert Dugan and his brother, James Dugan, were believed to have ridden with Colonel Glenn on the prior raid to Turner’s home.

The Loyalists arrived a little after 2 AM. They sent a few men to guard the rear before the main group approached the front door. Awake and aware of the visitors, poor old Mrs. Dugan listened to the men signaling to each other that all were in place just before she heard a pounding knock on the door. A loud demand for entrance immediately followed but her first thoughts went to Robert and James who were upstairs sleeping, having come home on leave for a quick visit with their mother.

Instead of opening the door right away, Mrs. Dugan ran upstairs to warn her sons. Robert tried to run. He crawled out the upstairs window and jumped from the rooftop “hoping to elude his pursuers by rapid flight under cover of darkness.” Unfortunately for the young captain, his leg broke from the fall and he was captured immediately. James Dugan tried to slide up the chimney but Ned Turner soon broke in and discovered his hiding place. Turner had the two young men held prisoner while he rode off in search of their cohorts in the killing of his brother.

Turner made his designated rounds. He found John Ford and Jacob Anderson at home. Much to their misfortune, Turner shot both men dead on the spot. He then tried the homes of Colonel Glenn and William Wilson but they were off with the army watching the British at Charleston. Feeling less than satisfied, Turner and the Loyalists returned to the Dugan residence where the two young soldiers remained in custody.

As Turner prepared ropes to hang Robert and James Dugan, their mother desperately pleaded with their captors. She looked into the faces of Turner’s men. Many of them were neighbor boys whom she had fed and helped take care of as they grew up. She found no pity in their faces. Instead, they made threats and taunted their captives, setting fire to a small storage shed in the front yard. The Tories strung up the two captives on a nearby tree and raised the rope until they began to struggle and choke. At that point, Turner lost his patience and began hacking at them with his sword. The Loyalists then “hewed the limbs and quivering flesh from the bodies of their suspended victims” until both were dead, leaving the mother to wail in anguish. She later buried them nearby in an unmarked grave where “no doubt good angels” keep vigil over their dust.[5]

The Annals provided a second graphic description of the mother’s grief: “The next morning their poor mother, accompanied by Robert Mars, found their bodies; one had his hand chopped off, the other a thumb and finger cut-off; one of their heads was literally split open! The weeping mother, and sympathetic friend, gathered their mangled remains, wrapped them up in sheets, and buried them without coffins! Horrible! Horrible! Is the exclamation of humanity; yet to such sad scenes must humanity come in Civil War!” [6]

There was a tradition in the back country that Bloody Bill Cunningham led the attack on the Dugans but the Annals author indicated that “I am sure it is a mistake. One who lived in those times, and who knew most of those who acted and suffered on that occasion, assured me that it was the sudden outbreak of two ferocious spirits, Ned and Dick Turner, raging like tigers to be slaked with blood!”

Ned Turner vs. the Towles Family

During his time in the back country, Ned Turner also carried on a well-known feud with the Towles family. Their problems may have started with the death of an in-law named Daniel Goggan, or perhaps political arguments eventually turned overly bitter since the Towles family were such staunch Whigs. In any event, one night while Daniel was home on leave from his duties under Gen. Francis Marion, Daniel found himself “surrounded by a body of Tories led by the celebrated and notorious Ned Turner. He [Daniel] knew that his life would be taken in any case, unless he could make his escape, which was impossible.” Goggan held out inside his house as long as possible but soon Turner’s men managed to set the place on fire. At that point, Goggan came out with his hands up but “was instantly shot down. After he was killed the flames were extinguished, and the house stood there for many years with its scorched and blackened timbers, a monument to the horrors of that night.”[7]

Ned Turner also murdered Daniel Gogan’s son-in-law, a fellow named Stokley Towles[8] who was also home on leave from the army. Unfortunately, while visiting, Towles fell sick with smallpox and had to be isolated. Knowing he would be killed if discovered by the Tories, the family stashed Towles in the thick swamps near the conjunction of the Saluda and Little Rivers.

Within a few days, Ned Turner showed up at the Towles home looking for him. His men “took two of Towles’s little boys up behind them on their horses and compelled them to go with them and show them where their father was hiding.” Once Turner succeeded in finding the sick man, he “killed him at once.”[9] In another of the annals, the murder of Towles is described thusly:

“I remember to have heard it said that one of the Towleses, being sick with smallpox, was concealed by his friends somewhere in the swamps of Saluda or Little River. The Turners, however, hunted him down with the perseverance of a sleuth hound, and that, helpless as he was when found, he was shot by Ned Turner.”[10]

Word of the murders and chaos in the back country spread quickly and Patriot militia under Andrew Pickens returned to the back country. Bloody Bill Cunningham retreated to Charleston and the safety of the British lines. It is likely that Ned Turner went with Cunningham since both men chose an escape to East Florida after the evacuation of Charleston in 1782. However, at least in the case of Ned Turner, he could not resist a final visit to family back home in the district during his later years.

Sometime around 1807 Turner tried to make his visit home. Knowing that many of the neighbors, including the Towles family, would be out to get him, Turner “was very cautious and used all the means in his power to keep clear” of his enemies. Unfortunately for him, word got out anyway and the Towleses quickly “set about hunting him up. They found him at the home of his aunt on a Sunday night and shot him. It seems that he was sitting in the door at the time and had no warning of the danger until they were within a few feet of him, when they fired and he fell forward on his face in the yard. Not doubting for a moment that their purposes was accomplished they then rode away. Turner, however, was entirely unharmed and as soon as the party was out of sight he arose, and, getting the ball out of his cravat, declared that he could have made a better shot with so good a ball. He left the country that night and never visited it again.”[11]

Once Turner left the area and headed back south to East Florida, his in-laws realized they needed to cover his escape. So, in “order to conceal the fact that he was alive and facilitate his escape, procured a coffin the next day, dug a grave and went through the form of burial. The Towleses never learned of his escape until after it was too late to pursue him.”[12]

After the revolution, Ned Turner joined Cunningham and the refugee Loyalists in East Florida. They linked up with Daniel McGirth and continued their plundering ways. Unfortunately for the Loyalists, they soon found themselves unwelcome in Florida as the British turned control over to the Spanish. Though his crimes are not enumerated, the Annals of Newberry tell us that Turner was “captured and imprisoned in the castle of St. Augustine, where he remained for more than 7 years and was only released after the purchase of Florida by the United States.”[13] But that must not have been the end for Ned Turner. Not much was written about his later life but the Annals author made this note: “I have lately heard with astonishment, that Ned Turner is still alive in Florida. If so, he must be verging on to 100. Wonderful indeed will it be, after his many hair breadth escapes in and since the Revolution, if God should spare him to be a centenarian.”

Conclusion

Ned Turner’s story goes to understanding what went on with the people of the South Carolina back country during the final phases of the American Revolution. Often thought of as a very messy time when neighbor turned on neighbor, the specific events are generally passed over by modern historians, consigning men like Ned Turner to the lost details of history. Perhaps that is where Turner should remain. After all, we only know Ned through his most dastardly acts. However, I believe there are still lessons to be learned by reviewing these events. Reminders of the danger presented in letting political passions spread beyond the political arena and spill into everyday life, and death. One last quote from the Annals seems to sum up the impact the war had in the Ninety Six District: “Heavy, however, were the calamities with which the Forks was visited – plantations were wasted, families were in poverty and want, and last but not least, nine heads of families in the six miles square, had been forever removed, Five were killed, two died in Ninety Six gaol, one on a prison ship at Charleston, and one” who died of smallpox before he could get home from the fighting.

Source Note – The story of Ned Turner all comes from a single source. By 1850 John Belton O’Neill had gathered enough tidbits about the family histories around Newberry to make group of records he deemed to be annals. In 1858 Mr. O’Neill consolidated his records into what became the Annals of Newberry. As O’Neill got older, John Chapman added to the Annals until 1892 when he published a two volume set appropriately called The Annals of Newberry: in Two Parts. The book contains family history handed down to generations after the revolutionary generation. As a result, the Annals would probably not be appropriate for second guessing information found in the Papers of General Nathaniel Greene. However, when recounting stories of the common folk and the plundering and murders that took place in the southern back country, family histories often represent the best (and often only) source for measuring the impact the war had on its participants.

[1] John Bolton O’Neil and John Chapman, Annals of Newberry (Newberry, SC: Aulte Houseall, 1892)

[2] Col. David Glenn was among the last emigrants from Ireland before the revolution. He came to the back country in 1774 and settled along the Enoree at a place known as Glenn’s Mills. Glenn was actually a Lieutenant Colonel of the militia regiment between the Broad and Saluda Rivers. He was known as a “Stern, uncompromising Whig” who once sacrificed a prisoner to save himself. Ibid., 194.

[3] The killing of Ned Turner’s brother is documented only by virtue of being given as the motivation for Ned Turner’s actions against the men in the Long Lanes Settlement raid.

[4] There is at least one conflicting account as to the date and motivation of the Dugan boys murder. John Bolton O’Neil may also be the original source of that information from an article called “Random Recollections of Revolutionary Characters and Incidents” published in the 1838 Southern Literary Journal and Magazine of Arts (Vol 4, No.1, Jul 1838). In that article, the Dugans are killed the night following Cowpens because the Tories sought revenge over James having taken a sword from a British officer. The sword itself was used to hack up the three brothers (adding a brother named William). That account doesn’t seem to name Ned Turner, or at least the sources I found the story in do not mention him. In the account chosen, I decided to leave the incident within the Bloody Scout period as indicated by John Bolton O’Neil in the Annals of Newberry. In my opinion, when comparing the conflicting accounts, it seems unlikely that Loyalists were operating the night after Cowpens with Tarleton and the British rushing back to join Cornwallis. Not much motivation for vengeance. On the other hand, the Ned Turner sources indicate the raid occurs while some of the men were home on leave after Eutaw Springs. I find this placement more logical in terms of fitting into the narrative of other events. Also, this is a Ned Turner story and deference was given to sources that identified him. However, given that Mr. Bobby Gilmer Moss who is recognized for incredible contributions to the detailed knowledge available on the southern campaigns placed the events after Cowpens, it would be remiss not to acknowledge the conflict in sources. Bobby Gilmer Moss, The Patriots at Cowpens (Leicester, England: Scotia Press, 1985, revised edition), 84.

[5] O’Neil and Chapman, Annals, 506.

[6] Ibid., 196.

[7] Ibid., 614.

[8] First name of Stokley comes from Ancestry.com: http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/TOWLES/2015-02/1423344157, accessed September 20, 2016.

[9] O’Neil and Chapman, Annals, 614.

[10] Ibid., 523.

[11] Ibid., 523.

[12] Ibid., 536.

[13] Ibid., 523.

3 Comments

Thank you for this encapsulation from the rather laborious Annals of Newberry. Ned is my gggg-grandfather and he (and these accounts) have fostered a more nuanced stance on the Revelutionary War.

Thanks for posting this excellent article about a colorful character from revolutionary SC. I do want to point out one correction however. Ned Turner’s mother was Elizabeth Spraggins. Members of the Spraggins family, as well as Elizabeth’s mother’s family, the Abneys, were close neighbors on the Saluda River and staunch whigs during the revolution. John Bolton O’Neil had some confusion about the Turner family, whom he would have known as a child. However, a review of Elizabeth Turner’s will from December 1812 (weeks before her death in 1813) shows her bequeathing several slaves and money to “Edward” (Ned), as well as the wife and children of his deceased brother Richard (Dick). This story illuminates the distress many families faced during the revolution – a largely untold story of conflicting loyalties during the birth of our nation.

Thanks for this information on the Turner family. I am doing research on the Towles family who were neighbors of the Turners, and the Abneys. I read accounts of the animosities between these families and how it led to murder. Ned is said to have murdered Stockley Towles and his brother, Oliver’s, father-in-law, Daniel Goggins. Bloody Bill Cunningham murdered Oliver Towles and his brother, or father, John Towles. I would love to know if the John Towles murdered by Bloody Bill was the father and if it can be proved. Would you have a clue?