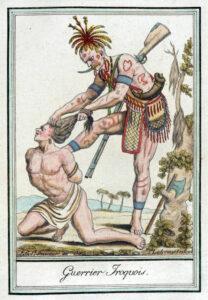

Scalping, the removal of the scalp from the head often for use as a trophy, is usually regarded as a uniquely sanguineous Indian practice confined to America’s distant colonial past. However, little remembered today is the important role the practice played during the Revolutionary War. While traditionally seen by colonials as a symbol of Indian barbarity, the role of scalping was reimagined during the Revolution as “Englishmen scalped Englishmen in the name of liberty.”[1] Throughout the war Patriots and Tories scalped to terrorize their foes while also claiming that their enemy’s willingness to scalp proved that their cause embodied Indian savagery.

Accusations of scalping emerged as early as the first engagement of the war at Lexington and Concord. Ensign Jeremy Lister of the 10th Regiment of Foot, serving under Capt. Parsons, reported finding “4 men of the 4th company killd who [were] afterwards scap’d their Eyes goug’d their Noses and Ears cut of, such barbarity … could scarcely be paralelld by the most uncivilised Savages.”[2] Gen. Thomas Gage, the royal governor of Massachusetts and commander in chief of British forces in North America, sought to capitalize on the rumors of atrocities committed by the minutemen at Concord in an attempt to swiftly turn public opinion against the Patriot cause. He reported his own version of the events in a broadside published by Loyalist printer John Howe, claiming that the three companies commanded by Parsons “observed three Soldiers on the Ground one of them scalped, his Head much mangled, and his Ears cut off, tho’ not quite dead; a Sight which struck the Soldiers with horror.”[3]

While it remains unclear if the minutemen did in fact scalp British troops at Concord this mattered little in the ensuing controversy and press war that followed the battle. The British press lambasted American colonials for embracing the cruel tactics of Indian war, claiming that they used “savageness unknown to Europeans” and even declared sardonically “their humanity is written in the indelible characters with the blood of the soldiers scalped and googed [sic] at Lexington.”[4] The Massachusetts Provincial Congress responded to the allegations of Indian savagery by claiming that Gage’s account was fraudulent and meant only to “dishonor the Massachusetts people, and to make them appear to be savage and barbarous.”[5] While the scalping incident at the North Bridge, whether real or not, would soon fade into obscurity, the British and Loyalist press’s likening of Patriots to Indian savages due to their willingness to scalp set an important precedent which would persist until the end of the war.

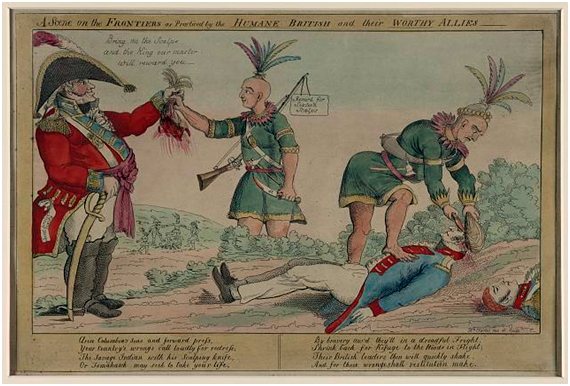

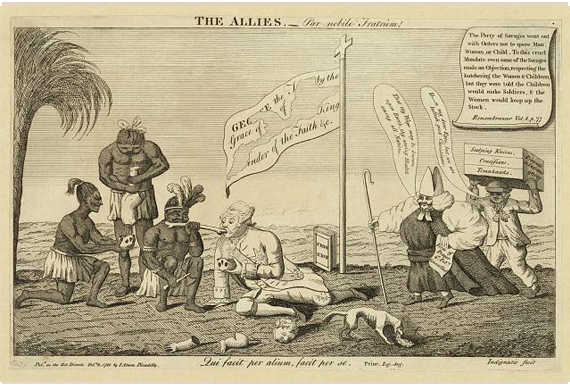

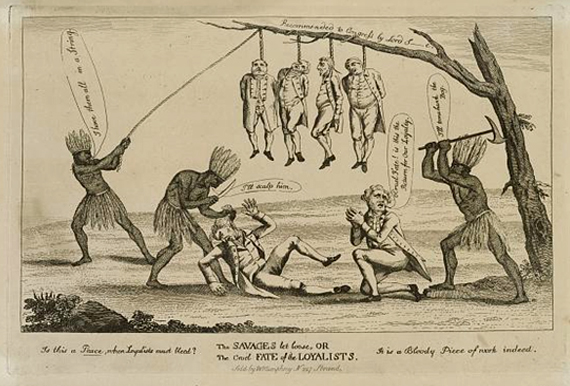

Ironically, despite the incident at Concord, the most infamous reports of scalping from the Revolutionary period come from the Patriot press in accusations leveled against British and Loyalist forces. These accusations emerged as effective weapons to garner support for the Patriot cause by stimulating deep-seated racial fears as when “speaking of scalping, founding American citizens spoke meaningfully, making sense of their world, joining Indian barbarity to imperial cruelty.”[6] Consequently, as the war progressed, British and Loyalist troops were often charged with encouraging their Indian allies to scalp Continentals and even civilians. Based mostly on hearsay, the Lieutenant Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs Henry Hamilton became a hated figure along the American frontier and was derisively named the “Hair-buyer General” following accusations that he incited “the Indians to perpetuate their accustomed cruelties” including “the indiscriminate murther [sic] of men, Women and children with the usual circumstances of barbarity practised [sic] by the Indian savages” by providing “standing rewards for [white] scalps, but [offering] none for prisoners.”[7] While most reports of scalping perpetrated against Patriots involved allied Indian groups, these accusations often extended to British and Loyalist troops themselves. The Georgian Loyalist, and commander of the King’s Rangers militia, Thomas Brown was vilified across the South for embracing the tactics of Indian war to instill terror in his Patriot enemies, particularly scalping the sick and wounded, an accusation he long denied.[8]

The best-known case of scalping during the Revolution is the tale of Jane McCrea, a women who was engaged to a Loyalist lieutenant when she was abducted, scalped, and shot by Indians under the command of British Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne. Continental commanders immediately realized that the incident could be used to garner greater popular support and military recruits for their cause. To this effect, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates wrote a scathing letter to Burgoyne in September 1777, with copies sent to Congress and many Philadelphia newspaper presses, primarily blaming the British for the incident:[9]

That the savages of America should in their warfare mangle and scalp the unhappy prisoners, who fall into their hands, is neither new nor extraordinary; but that the famous Lieut General. Burgoyne, in whom the fine gentleman is united with the soldier and the scholar should hire the Savages of America to scalp Europeans and the descendants of Europeans; nay more, that he should pay a price for each scalp so barbarously taken, is more than will be believed in England until authenticated facts shall in every Gazette, convince mankind of the truth of the horrid tale – Miss McCrea, a young lady lovely to the sight, of virtuous character and amiable disposition, engaged to be married to an officer in your army; [she] was … carried into the woods, and there scalped and mangled in the most shocking manner … [by] murderers employed by you.[10]

Once distributed throughout the colonies the tale of Jane McCrea led to an explosion of anti-British and anti-Loyalist literature, much of which contained rhetoric directly conflating the Tory cause with Indian cruelty.

This rhetoric of British and Indian convergence took many forms following the scalping of McCrea. A popular 1778 poem by Wheeler Case memorialized McCrea by blaming the British directly for supporting the atrocity and likened them to savages:

Oh cruel savages! what hearts of steel!

O cruel Britons! who no pity feel!

Where did they get the knife, the cruel blade?

From Britain it was sent, where it was made.

The tom’hawk and the murdering knife were sent

To barb’rous savages for this intent.[11]

The strongest proponents of the Revolution used this new rhetoric of likening the British to Indian savages to great effect. Thomas Paine wrote to British military official Sir Guy Carlton claiming that the British and Loyalists did not differ from Indians in either their conduct or character. Paine even added that while the “history of the most savage Indians does not produce instances [of cruelty] exactly of this kind,” as Indians at least had “formality in their punishment,” there was not a more “detestable character, nor a meaner or more barbarous enemy, than the present British one.”[12] These attacks on the British and Loyalists for supporting and enabling Indian cruelty eventually took on an explicitly racial tone. To this effect, an anonymous writer for the Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal declared in 1781 that the British, despite all their achievements in the last centuries, were “the same brutes and savages they were when Julius Caesar invaded … for it is certain their mixture with the Saxons and other foreigners, has done very little toward their civilization,” explaining why they were willing to scalp and become “so bloody, so barbarous a nation … whose hands have been, and will yet be dyed in [Americans’] blood.”[13] As a result of this rhetoric, even some English writers began to question Britain’s alliances with Indians. In his 1778 book English Humanity No Paradox, or An Attempt to Prove that the English Are Not a Nation of Savages, Edward Long harshly criticized British policy in the New World, writing that they had become “patrons and abettors of Wanton Homicide,” by inciting “Cannibal Indians to scalp, tomahawk, and torture, with undistinguishing fury … [leading to] killings in cool blood, rapes, torturing, rapines, and devastations.”[14] Evidently, British cruelty and eagerness to scalp Americans was now understood by many as a natural product of their immutable racial and national character. Through their denouncements of scalping, Patriots now argued that Englishness, which they had celebrated just years prior, was a natural condition no better than that of savage Indians.

The great irony of this rhetoric is that at the very same time Patriots were also scalping for their own purposes, often using this racial rhetoric of British and Loyalist savagery to justify violence against these groups. This new readiness to scalp was a significant transformation, as in earlier American history colonials only approved when done through bounties so that the actual act of scalping remained out of sight and was carried out by allied Indians rather than whites.[15] However, this attitude began to change during the French and Indian War as colonial authorities began to offer scalping bounties advocating that whites should scalp as symmetrical retribution against the tactics of Indian warfare. The New English colonies issued scalping bounties by 1755, most famously the Phips Proclamation in Massachusetts which offered fifty pounds for the scalps of Penobscot Indians, while the Deputy Governor of Pennsylvania Robert Morris proclaimed a general bounty for Indian scalps in 1756.[16] The purpose for these bounties was explicitly racial and genocidal with Pennsylvania government official James Hamilton justifying the bounties as “the only way to clear our Frontiers of … Savages, & … infinitely cheapest in the end.”[17]

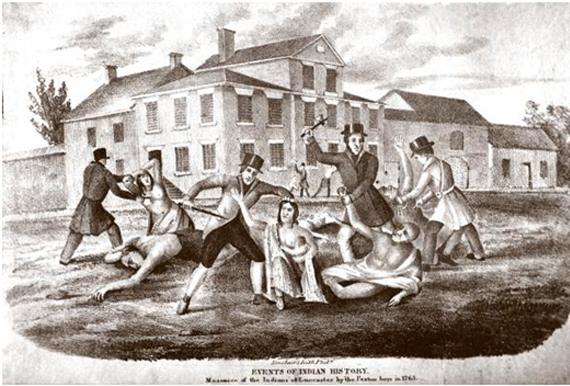

Once regarded as a uniquely violent form of Indian cruelty, the practice was thus increasingly normalized among colonial whites. David Owens, a British deserter who had taken refuge with Indians and married a Delaware women, gained fame during Pontiac’s Rebellion after he murdered his companions, shooting two, killing a third with a hatchet, and tomahawking to death the women and children. He then scalped the adults in an attempt to collect a scalping bounty and make peace with British authorities as he returned to Philadelphia.[18] Following the war the Paxton Boys, a vigilante group composed of Scottish and Irish frontiersmen from central Pennsylvania, were often accused of emulating Indian savagery in their attempts at retribution against Native Americans. These accusations included taking an “enemy Indian … examining him … [and as] the Indian begged for his life and promised to tell all what he know … they shott him in the midst of them, scalped him and threw his Body into the River.”[19] Other colonial scalpers were primarily motivated by the potential profits from state sponsored bounties. During the French and Indian War freelance soldier James Cargill of Newcastle, Maine, led a scouting party which killed and scalped twelve peaceful Penobscot Indians to receive bounty payments, which he received after being arrested, put on trial, and found not guilty of murder.[20] While the actual effectiveness and profitability of these bounties is much debated it undoubtedly got numerous whites to scalp on an unprecedented scale. [21]

This transformation in colonial attitudes reemerged during the Revolutionary period as the war allowed Americans to find new justifications to scalp their foes. Indians still remained the most common targets. During the Sullivan Expedition in 1779, an offensive against frontier Loyalists and the British allied nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, Lt. William Barton reported that near the town of Canesaah, New York, Continentals captured, killed, and scalped fleeing Indians.[22] During the same expedition, celebrated Patriot sharpshooter Timothy Murphy reportedly scalped an “unsuspecting elder … [and] two innocents,” and “bragged of killing and scalping every Native he happened across.”[23] It is important to note that while independent soldiers preformed many if not most incidents of scalping by Continentals, high-ranking officers occasionally encouraged it. Following the siege of Fort Sackville in Indiana the American commander George Rogers Clark ordered that four Indian prisoners be executed with tomahawks and scalped before their bodies were thrown in the river and their scalped hair displayed on the fort’s main gate.[24] While the claim is likely embellishment meant to sully his reputation, Clark’s British enemies also asserted that he had performed the scalping himself. Henry Hamilton’s aide Lt. Jacob Schieffelin reported that Clark led the ritualized execution, as he “took a tomahawk, and in cold blood knocked their brains out, dipping his hands in blood, rubbing it several times on his cheeks, yelping as a Savage.” Hamilton added that following the scalping Clark “spoke with rapture of his late achievement, while he washed of the blood from his hand’s stain’d in this inhuman sacrifice.”[25] Ironically, Clark had merely a few weeks prior denounced the savagery of British and Indian conduct on the frontier in a letter to then Virginia Governor Patrick Henry and singled out Hamilton, who was among the captured at Fort Sackville, as “The Famous Hair Buyer General.”[26] Nevertheless, Patriots widely approved and often celebrated such atrocities openly when committed against Indians, like the Providence newspaper American journal and general advertiser, which in 1779 praised Continental Brig. Gen. Edward Hand for destroying the Iroquois capital of Onondaga and collecting a “great number of scalps” in the process.[27]

Evidently, like in the French and Indian War before it, the scalping of Indians by white Americans was an important, but largely uncontroversial, reality of fighting in the Revolutionary War, especially along the frontier. However, far more contentious was Patriots’ newfound willingness to scalp other Englishmen, something that would have been unthinkable in earlier colonial history. A particularly interesting case is that of the aforementioned Loyalist militia leader Thomas Brown, who, in August 1775, was abducted from his home, tarred and feathered, and scalped by a Patriot mob. Brown later recounted the incident in a letter sent to British commander Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis:

I was ordered to appear before a committee then sitting in Augusta, and on my refusal to attend, a party consisting of 130 armed men headed by the committee surrounded my house in South Carolina and ordered me to surrender myself a prisoner and subscribe a traitorous association. I told them my determination to defend myself if any person presumed to molest me. On their attempting to disarm me, I shot one of the ringleaders … Being o’erpowered, stabbed in many places, my skull fractured by a blow from a rifle, I was dragged in a state of insensibility to Augusta. My hair was then chiefly torn up by the roots; what remained, stripped off by knives; my head scalped in 3 or 4 different places; my legs tarred and burnt by lighted torches, from which I lost the use of two of my toes and rendered incapable of setting my feet to the ground for 6 months. In this condition, after their laying waste a very considerable property, I was relieved by my friends and conveyed to the interior parts of South Carolina.[28]

Ironically, it was this public humiliation that inspired Brown to escape to Florida and form a Loyalist militia group, the King’s Rangers, which would be plagued by accusations of scalping from Patriots throughout the war.[29] While the dramatic nature of Brown’s scalping is unique, it was not an isolated incident. In fact, George Clark’s men captured and scalped British subject Francis Maisonville. Hamilton once again claimed that Clark was directly responsible, testifying that he “orderd one of his people to take off [Maisonville’s] scalp, the man hesitating he was threatened with violent imprecation, and had proceeded so far as to take off a small part when the Colonel thought proper to stop him.”[30] While Hamilton’s account should be read skeptically, it is important to note that Clark vigorously denied these allegations, blaming the scalping of the white Maisonville on two of his subordinates, while he had no such apprehension in admitting to directly ordering the scalping of Indians at Fort Sackville.[31]

During the American Revolution, scalping, while still ostensibly regarded as a savage Indian practice, emerged as a valuable tool for combatants. However, rather than solely expecting Indians to scalp, as had been the practice in most previous colonial wars, both Patriots and Loyalists were now willing to directly encourage allied Indians and even use scalping themselves as a means to terrorize their enemies, whether that enemy be an Indian or Englishman. At the same time, each side claimed that their enemy’s use of scalping proved that the opposed cause embodied Indian savagery. This new understanding of scalping would remain a central tension in Anglo-American warfare until the end of the War of 1812 and would fundamentally shape American policy and conduct in Indian Wars throughout the nineteenth century.

[1] James Axtell, “Scalping: The Ethnohistory of a Moral Question,” in The European and the Indian: Essays in the Ethnohistory of Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 241.

[2] Jeremy Lister, The Concord Fight: Being So Much of the Narrative of Ensign Jeremy Lister of the 10th Regiment of Foot as Pertains to His Services on the 19th of April, 1775, and to His Experiences in Boston During the Early Months of the Siege (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931), 27.

[3] Thomas Gage, A Circumstantial Account of an Attack that Happened on the 19th of April 1775, on his Majesty’s Troops (Boston: Broadside Printed by John Howe, 1775).

[4] John Moir, Obedience the best charter, or, Law the only sanction of liberty: in a letter to the Rev. Dr. Price (London: Published for Richardson and Urquhart, 1776), 55. “An Answer to the Declaration of Independence,” in The Scots Magazine, 39 (1777), 237.

[5] A Narrative of the Excursion and Ravages of the King’s Troops Under the Command of General Gage, On the nineteenth of April, 1775 (Worcester: Printed by Isaiah Thomas, by order of the Provincial Congress, 1775).

[6] Gregory E. Dowd, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2015), 170.

[7] “Order of Virginia Council of State Placing Henry Hamilton and Others in Irons, 16 June 1779,” in The Papers of James Madison, vol. 1, 16 March 1751 – 16 December 1779, ed. William T. Hutchinson and William M. E. Rachal (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962), 288. “From Thomas Jefferson to Theodorick Bland, 8 June 1779,” in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 2, 1777 – 18 June 1779, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 286.

[8] Maya Jasanoff, Liberties Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary War (New York: Vintage, 2012), 45.

[9] Peter R. Silver, Our Savage Neighbors: How Indian War Transformed Early America (New York: WW Norton, 2009), 246.

[10] William Digby, The British invasion from the north: the campaigns of Generals Carleton and Burgoyne, from Canada, 1776-1777, with the journal of Lieut. William Digby, of the 53d, or Shropshire regiment of foot, ed. James P. Baxter (Albany: J. Munsell’s Sons, 1887), 262.

[11] Rev. Wheeler Case, Revolutionary memorials (New York: M.W. Dodd, 1852), 39.

[12] Thomas Paine, “A Supernumerary Crisis. To Sir Guy Carleton,” in Crisis Papers (Philadelphia, 1782).

[13] The Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal, September 19, 1781.

[14] Edward Long, English humanity no paradox: or, an attempt to prove, that the English are not a nation of savages (London: Printed for T. Lowndes, 1778), 81-82, 90.

[15] Gregory Evans Dowd, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2015), 183.

[16] Henry J. Young, “A Note on Scalp Bounties in Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania History 24 (1957), 207.

[17] Silver, Our Savage Neighbors, 161.

[18] “From Benjamin Franklin to [Peter Collinson?], 12 April 1764,” The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 11, January 1, through December 31, 1764, ed. Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1967), 180. Stephen Brumwell, Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755-1763 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 175.

[19] “Conrad Weiser to Governor Robert Morris, December 22, 1755,” in Colonial Records: Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania from the organization to the termination of the proprietary government. v. 11-16 Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania from its organization to the termination of the revolution (Philadelphia: J. Severns & Company, 1851), 763.

[20] Robert Francis Seybolt, “Hunting Indians in Massachusetts: A Scouting Journal of 1758,” The New England Quarterly, 3 (1930), 528-531. Michael Dekker, French & Indian Wars in Maine (Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing, 2015), 120.

[21] Silver, Our Savage Neighbors, 161-162.

[22] Frederick Cook ed., Journals of the military expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six nations of Indians in 1779; with records of centennial celebrations; prepared pursuant to chapter 361, laws of the state of New York, of 1885 (Auburn: Knapp, Peck & Thompson, Printers, 1887), 11.

[23] Barbara A. Ann, George Washington’s War on Native America (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2008), 94, 95, 97.

[24] Bernard W. Sheehan, “‘The Famous Hair Buyer General’: Henry Hamilton, George Rogers Clark, and the American Indian,” Indiana Magazine of History, 79 (1983), 20. Theodore Savas, and J. David Dameron, Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution (New York: Savas Beatie, 2010), 202.

[25] Sheehan, “‘The Famous Hair Buyer General’,” 21.

[26] “Clark to Patrick Henry, February 3 1779,” in George Rogers Clark Papers Volume VIII, 1771–1781, ed. Clarence Walworth Alvord (Springfield: Trustees of the Illinois State Historical Library, 1912), 97.

[27]American journal and general advertiser, May 7, 1779. Dowd, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier, 213.

[28] “Brown to Cornwallis, 16 July 1780,” in The Cornwallis Papers Volume 1 The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in The Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, ed. Ian Saberton (East Sussex: Naval and Military Press, 2010), 278.

[29] Wayne Lynch, “The Making of a Loyalist,” Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/01/making-loyalist/, accessed July 3, 2016.

[30] John D. Barnhart, ed., “Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton’s Apologia,” Indiana Magazine of History, 52 (1956), 394.

[31] Dowd, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier, 185.

3 Comments

According to historian Cyrus Eaton, in 1745 on the Eastern frontier (Maine) the Provincial bounty for every Indian captive or scalp turned in was £100 paid to soldiers and £400 paid to unpaid volunteers. The aforementioned James Cargill (later Colonel) was much feared by the Penobscot Indians. It was once reported that when he was challenged for turning in the scalp of a child for the bounty, he replied something like: “From nits, lice do grow.”

May I call attention to the more than a hundred and a quarter accounts of scalping in the Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, mainly transcribed by Will Graves and C. Leon Harris? These records, many of them by eye-witnesses or actual scalpers, might enrich any articles such as Zachary Brown’s. It seems to me that historians have only just begun to avail themselves of this great ongoing archive.

Scalping was a common practice among Pawnees and Otoe. One of the survivors of Pedro de Villasur expedition into Nebraska (1720) was scalped and managed to return to Santa Fe with the help of allied Apaches. Scalping of the fallen soldiers can be seen in the Segesser buffalo hides depicting the last stand of Villasur against a combined force of French and Pawnees. This practice was hateful to Spaniards who instead offered a reward for captive Indians. This practice, known as redención, fostered trade, particularly between Spaniards and Comanches. Many of the Indians redeemed thru trade with Comanches ended up as auxiliary troopers known as genizaros; in any case, they had to serve as servants or soldiers for an average of two years before being released as free citizens—most settled in rancherías or misiones, others were engaged as presidio troopers.