Brig. Gen. William “Scotch Willie” Maxwell usually receives scant attention in books covering the American Revolution. If the author mentions Maxwell at all, the cursory biographical sketch usually focuses on his nickname, his heavy drinking, and his Irish origin. This colorful portrayal does not give credit to Maxwell’s many contributions during the war, most significantly at the Battle of Connecticut Farms in June 1780. Maxwell also commanded men in New Jersey during the winter of 1777 and at the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth Courthouse. He participated in the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, leading his men through Iroquoia, burning towns and fields of crops. An examination of the wartime correspondence between Brigadier General Maxwell and the commander-in-chief, Gen. George Washington, shows a close, productive working relationship until Maxwell’s sudden resignation from service in the summer of 1780.

William Maxwell was born and raised in County Tyrone, Ireland. He immigrated to America and settled in Sussex County, in northwestern Jersey, around 1747. He never lost his thick Ulster accent, which prompted his men to call him “Scotch Willie.” He enlisted in the militia following the outbreak of hostilities over the Ohio country, and served in the disastrous Braddock Expedition in 1755. He later served as a lieutenant in the regiment called the Jersey Blues and likely was on the 1758 Abercrombie campaign that also ended disastrously at the Battle of Carillon (Fort Ticonderoga). After the French and Indian War ended, Maxwell served as a British army commissary on the frontier at various posts including Fort Michilimackinac. In 1775 Maxwell received a commission as a colonel of the 2nd New Jersey Regiment in the Continental Army, eventually rising to the rank of brigadier general.

He marched to the relief of the survivors of Montgomery and Arnold’s failed Quebec expedition in early 1776 and fought at the Battle of Three Rivers before the Continental Army retreated to Fort Ticonderoga. Lt. Col. Israel Shreve, second in command of Maxwell’s regiment, spoke highly of Maxwell’s leadership during the retreat from Three Rivers “by Leading our people through the woods, Round the enemy that had marched a strong party up the Road, ahead Laid in wait for our people, and consequently saved the Remains of our party, and if there was any merit Due to any, it ought to be to him who conducted the Retreat, although we see the honor given to others, who do not Deserve it.”[1]

Colonel Maxwell wrote to Congress following the campaign that “he finds himself much aggrieved by having a younger officer, viz: Colonel St. Clair, promoted over him.”[2] Maxwell concluded by assuring Congress “he would have quitted the service immediately, but that the present alarming state of this country requires his presence in the field; therefore he takes this method to inform you wherein he finds himself aggrieved, that your honorable House may redress it if you find his complaint well founded.”[3] Rank would be a point of concern for men under Maxwell later in the war.

After leaving Fort Ticonderoga, Maxwell joined the Continental Army in New Jersey. Washington gave him orders: “As it is a Matter of the utmost Importance to prevent the Enemy from crossing the Delaware, and to effect it, that all the Boats and Water Craft should be secured or destroyed.”[4] Securing the boats prevented the British from pursuing the Continental Army into Pennsylvania and also provided Washington and the army with the vessels they used to cross the Delaware on Christmas night 1776. This is the first of many examples of Washington entrusting an important task to Maxwell. Two days after capturing the Hessian garrison at Trenton, Washington wrote a letter to Maxwell informing him of the success “of an enterprise which took effect the 26th Instant, at Trenton.”[5]

In the same letter, Washington apprised Maxwell of his plans to cross the river again with his army “for the purpose of attempting a recovery of that Country from the Enemy, and as a diversion on your quarter may greatly facilitate this event by distracting and dividing their troops, I must request you will collect all the force in your power together, and annoy and distress them, by every means which Prudence can suggest.”[6] This foreshadowed the actions at the Second Battle of Trenton and Battle of Princeton. Taken as a whole, this ten day campaign reversed the repeated defeats of 1776 and boosted morale within the Army and the nascent nation.

Maxwell took over command of the militia in Morristown in late December 1776, and was directed “therewith to give all the protection you can to the Country, and distress to the Enemy by harassing of them in their Quarters & cutting off their Convoys.”[7] Washington also encouraged Maxwell to recruit soldiers for the New Jersey Continental regiments because one-year enlistments were expiring. Maxwell’s mobilization of New Jersey militia and work in Morristown preceded the Continental Army’s encampment in Morristown in January 1777 and prepared them for a series of small scale battles between British foraging parties and New Jersey militia coordinating with Continentals.

Maxwell proved to be adept at this “hit-and-run open style of warfare the militia was successfully practicing against the British.”[8] He defeated Col. Charles Mawhood at Rahway on February 23 who had under his command the Third Brigade, a battalion of grenadiers and another of light infantry, showing superior command of the battlefield. A repeat performance pitted Maxwell and his men against two thousand British troops at Bonhamtown on March 8 where they “incautiously attacked the Americans, and ran into what a British officer called a ‘nest of American hornets’ and were defeated.”[9] These battles resulted in increased experience and confidence in American arms.

In preparation for the coming campaign season, Washington created a light infantry unit to “observe and report on enemy activities and movements, and engage in limited combat when appropriate.”[10] Washington selected Maxwell to command the newly formed elite force. This is perhaps the greatest example of Washington’s confidence in Maxwell’s ability. Washington recognized Maxwell’s leadership during the February and March fighting and his seniority among brigadier generals in conferring upon him this prestigious post.

Maxwell commanded the light infantry at the Battle of Brandywine. His men screened the road from Elkton, the approach to the center of Washington’s army, the direction Washington expected the British under General Howe to attack. Maxwell and the light infantry encountered General von Knyphausen’s force, whose mission it was to distract Washington’s center from Howe’s flanking force. His men fought a fighting retreat, delaying von Knyphausen’s advance, at the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge. After a seven hour fighting retreat, Maxwell’s men broke and fled in the face of a British bayonet charge. Howe famously attacked the flank where Maj. Gen John Sullivan commanded, the same tactic used to great success at the Battle of Long Island in 1776. The Battle of Brandywine, a British victory, did not end as Howe had hoped: the majority of Washington’s Continental Army was intact and able to fight another day.

At the Battle of Germantown, Washington attempted to strike a devastating blow against the British. While three thousand British soldiers occupied Philadelphia, the bulk of the army took quarters in the vicinity of Germantown, just northwest of Philadelphia. Washington’s plan called for a coordinated attack of four columns converging on British positions in the early morning. Even the best trained army would have had difficulty executing such an ambitious plan. Lord Stirling commanded the reserve, which included Maxwell’s brigade.

The savage fighting around Cliveden, also known as the Chew house, marked a shift in the battle. Initial American successes against surprised British forces were lost as part of the 40th Regiment of Foot occupied an imposing stone house. Rather than leave a castle in his rear, Washington listened to the advice of his artillery chief, Henry Knox, and decided to halt the advance and take Cliveden. Maxwell’s brigade was called upon to assault the house while Knox’s artillery attempted to pummel it into submission. Repeated attacks created a hellish, charnel scene as Americans fell trying to take the well defended position. Seeing that surprise had been lost and that his forces met with increasing resistance and losses, Washington ordered a withdrawal. With the British firmly lodged in Philadelphia, the Continental Army selected Valley Forge as their winter encampment site.

Winter encampments like Valley Forge and Morristown are remembered best for the hardships soldiers faced in terms of weather, disease, and lack of food. Winter encampments were also the time for court martial cases, a way to resolve problems that arose during the preceding campaign season. Maxwell found himself facing a charge in the aftermath of the Philadelphia campaign “That he was once, during the time he commanded the light troops, disguised with liquor in such a manner as to disqualify him in some measure, but not fully, from doing his duty; & that once or twice besides, his spirits were a little elevated with liquor.”[11] Maxwell’s accuser, Lt. Col. William Heth of the 3rd Virginia regiment, wrote to Daniel Morgan of his actions, hoping that Maxwell would

be recalld, and have this day delivered his Excellency, such charges for Misconduct, and unofficer-like behavior, as must undoubtedly reduce him – He has some-how or another acquird a Character, which by no means fits him – The bravery of the Corps on the 11th would have added something more to his reputation, had the officers under him been such, as were afraid to speak their sentiments – You know my disposition – & need not be told the style in which I have mentioned him.[12]

The court martial found that “Brigadier General William Maxwell, while he commanded the light troops, was not at any time disguised with liquor, so as to disqualify him in any measure from doing his duty – They do therefore acquit him of the charge against him.”[13] Generals Wayne, Sullivan, and Stephens all faced court martial trials during this winter. Wayne and Sullivan were similarly acquitted of the charges while Stephens was cashiered from the service for his intoxication and poor command of his troops at Brandywine where they fired upon friendly soldiers.

Officers in the New Jersey Brigade echoed Heth’s low opinion of Maxwell. In a letter to the Continental Congress dated March 8, they wrote that

without partiality or the least personal pique, we are obliged to represent the character of Brigadier‑General Maxwell, in the following manner; That, from a natural incapacity of genius, he is and ever will be unable to discharge the duties of his exalted Station with advantage to his country, and reputation to its arms. That (from) this want of industry and application of his slender abilities, he remains totally ignorant of military discipline, and unacquainted not only with his own duty, but that of the officers, whom he is appointed to command. He is destitute of address, and without fortitude: so that the officers of his Corps, let their abilities be what they may, can never promise either honour to themselves, or service to their country.[14]

The letter’s signers included Col. Israel Shreve, Col. Matthias Ogden, and Lt. Col. Francis Barber. Their letter can be seen as a first attempt to oust Maxwell from command.

Not content with just an acquittal, Generals Wayne, Sullivan, and Maxwell together wrote a letter to Washington expressing their displeasure about “our malignant Accusers remaining in Office, without Reprimand, or Censure, triumphing at the trouble they have unjustly occasion’d us, with impunity to themselves.”[15] They feared the consequences of scheming subordinate officers presenting charges against them to pave their own way for career advancement and therefore desired “that when the Accusers not only fail, but appear to have made a false and malicious Attack, some Punishment should be pointed out against them.”[16]

Maxwell’s brigade secured Valley Forge against the enemy, consistent with his orders to interrupt “the communication with Philadelphia – obtain intelligence of the motion, and designs of the enemy – and, aided by the Militia, prevent small parties from patrolling, to cover the market people.”[17] Similarly, Washington later entrusted Maxwell with the task of preparing his brigade to coordinate with New Jersey militia under Gen. Philemon Dickinson to harass the expected British march across New Jersey to their base in New York. Maxwell and Dickinson had previously collaborated to great effect in early 1777.

Washington ordered Maxwell to “keep your Brigade when assembled, in such a situation as will be most consistent with its security, and best calculated to cover the country and annoy the enemy, should they attempt to pass through the Jerseys, which there are many powerful reasons to suspect they intend.”[18] Washington desired that Dickinson and Maxwell together slow the march of the British by “hanging on their flanks and rear, breaking down the Bridges over the Creeks in their route, bloking up the roads by falling trees and by every other method, that can be devised.”[19] The previous year, General Burgoyne and his army’s march south through upstate New York had been similarly harried by militia and Continentals with trees blocking their route and bridges destroyed.

Maxwell marched his men to Mount Holly and later followed through on Washington’s orders. On June 22, Washington sent Col. Daniel Morgan’s riflemen to bolster Maxwell’s force as they shadowed the British. Given Maxwell’s position on the British flank, Washington ordered him “to keep up a constant correspondence as the movements of this Army must be governed wholy by the intelligence I receive from Genl Dickinson and yourself, & as an half hour may make much difference, I must intreat you to date accordingly.”[20] Washington also notified of Morgan’s presence on the British right flank and urged him to “give them all the annoyance you can on their left also.”[21] The Battle of Monmouth, thanks to Washington’s battlefield leadership, resulted in a draw in which the British army left the ground to the Continental Army. On the day after the battle, Morgan, Maxwell, and the New Jersey militia “were assigned to harass the enemy rear and pick up stragglers and deserters.”[22]

After harassing the British march to Sandy Hook, Maxwell moved his force to Elizabethtown, where he monitored British fleet and troop movements for Washington. Washington ordered Maxwell to winter in Elizabethtown with the New Jersey Brigade in order “to prevent the Enemy stationed upon Staten Island from making incursions upon the main and also to prevent any traffic between them and the inhabitants.”[23] During the winter of 1778-79, Maxwell kept Washington informed on many topics: prisoner exchanges, desertion, and British recruitment of Loyalists.

Officers who were dedicated to the cause sought to redress their grievances through letters to the New Jersey legislature, warning that the state of their pay threatened the army with dissolution. Maxwell informed Washington that the 1st New Jersey Regiment threatened to disband if their demands for better pay were not met. Washington received these letters with “infinite concern. There is nothing, which has happened in the course of the war that has given me so much pain as the remonstrance you mention from the officers of the 1st Jersey Regiment.”[24] This would have pained Washington at any time, but in light of preparations for the Sullivan Expedition the conduct of the officers “has an air of dictating terms to their country, by taking advantage of the necessity of the moment.”[25]

Jonathan Forman, a captain in the 1st New Jersey, responded to Washington on behalf of his regiment, relating that it “has made us very unhappy that any act of ours should give your Excellency pain.”[26] The welfare of the officers’ families and the horrible state of their finances compelled them to submit their ultimatum. Forman reminded Washington that “we love the Service, and we Love our Country; but when that Country gets so lost to virtue and justice as to forget to support its servants, it then becomes their duty to retire from the service.”[27] Fortunately, Lord Stirling intervened and, with the cooperation of the legislature, secured “£200 … paid to each Commissioned Officer & 40 dollars to each Soldier to enable them to pay their debts & to fit them for the Campaign.”[28]

While Stirling wrote to Washington of this compromise, Washington wrote to Maxwell of his opinions regarding the officers’ grievances, specifically the issue of pay. Washington felt “all that the common Soldiery of any Country can expect is food and cloathing – The pay given in other armies is little more than nominal – very low in the first instance and subject to a variety of deductions that reduce it to nothing.”[29] Washington went further and claimed that the “troops have been uniformly better fed than any others – they are at this time very well clad and probably will continue to be so – While this is the case they will have no just cause of complaint.”[30] Washington wrote this during the stress of organizing the Sullivan expedition, a priority of the 1779 campaign and one in which Maxwell’s men were slated to participate,[31] and can be excused for the hyperbole in the letter.

Washington’s correspondence to Sullivan reflects this disparity between his claim of well clad soldiers and the reality. In a March 24 letter from his headquarters at Middle Brook, Washington described efforts to procure thousands of pairs of shoes and overalls as well as thousands of hunting shirts.[32] On the 31st, Washington reiterated the purpose of the expedition: “the total destruction and devastation of their settlements (Six Nations tribes allied with the British) and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”[33] Washington insisted upon the total destruction of Iroquoian towns because “future security will be in their inability to injure us the distance to which they are driven and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire (them).”[34] Sullivan strictly followed Washington’s orders, wreaking devastation and forcing homeless Iroquois refugees to seek shelter at British forts like Niagara. Maxwell was present at the campaign’s sole battle, the battle of Newtown, in which his brigade acted as a reserve.[35]

Maxwell and his brigade, after their service in the Sullivan expedition, marched south to New Jersey for the winter encampment of 1779-1780, which proved to be the coldest winter ever recorded. The army survived the long, freezing winter, and Maxwell, along with his men, made a significant, if largely forgotten, contribution to the war effort. On June 6, 1780, Lt. Gen. Baron von Knyphausen, the Hessian commander of New York in Sir Henry Clinton’s absence, invaded New Jersey with six thousand soldiers. The British and Hessians knew of the recent mutiny of the Connecticut Line and saw this as their opportunity to end the war with a quick strike against Morristown.

Knyphausen and his army outnumbered the Continentals two-to-one, but the New Jersey militia responded to the alarm guns and blazing beacons, mobilizing against the threat. Maxwell fought back the British and Hessians at Connecticut Farms with his brigade, members of Washington’s Life Guard under Maj. Caleb Gibbs, and New Jersey militia, forcing the enemy to withdraw. The American defense impressed Capt. Johann Ewald, who commanded Hessian jaegers in the British advance. Ewald wrote that “General Maxwell, who was no mediocre general … stationed himself in a good position … where his front was covered by a marshy brook which cut through a range of hills and by marshy woodlands. Moreover, one could not get near his position at all, because of the narrow approaches at the flanks which the Americans had strongly occupied.”[36] Knyphausen then received word that Clinton’s fleet, fresh from victory in Charleston, approached New York, convincing Knyphausen to withdraw and await his commander’s orders and additional men.

In the general orders of June 22, 1780 Washington singled out the New Jersey Brigade for their role at Connecticut Farms, expressing “the high sense he entertains of the Conduct and Bravery of the officers and Men of Maxwell’s brigade in annoying the Enemy in their incursion of the 7th instant – Colonel Dayton merits particular thanks.”[37] Washington, in a letter to the President of Congress, commended the militia who “have turned out with remarkable spirit, and have hitherto done themselves great honor.”[38]

On June 23, 1780 a second British advance under Knyphausen met resistance as Quartermaster General Nathanael Greene, Washington’s trusted subordinate, commanded an outnumbered force of Continentals and New Jersey militia. Washington left Greene in command of the troops in and around Morristown, “consisting of Maxwell’s and Stark’s brigades, Lee’s corps, and the militia.”[39] This attack similarly failed to reach Hobart Gap, the approach to Morristown, and ended in British defeat. Washington, again writing to Congress, hailed the efforts of the militia, writing “The militia deserve every thing that can be said on both occasions. They flew to arms universally, and acted with a spirit equal to any thing I have seen in the course of the war.”[40] The Battle of Springfield marked the last major battle in the North and the end of significant British efforts in New Jersey.

After the key victories at Connecticut Farms and Springfield, Maxwell considered his future in the Continental Army. He worried about decreasing enlistments, the possibility of further mutinies in the army, and his own personal finances. The New Jersey Brigade in the spring of 1780 consisted of fewer than 900 men, far short of its quota of 1,556. The officers rightly feared a downsizing and anticipated the existing three regiments would go down to two, leaving one officer without a command. Washington explained the situation: “Dayton is the Senr. Colonel … and does not want to leave the Service. Shreve is the next oldest Colo. in Jersey and will not go out … Ogden is the youngest, and extremely desirous of staying, but cannot continue if Colo. Dayton remains in Service, in his present rank;” the situation therefore came down “to this Issue, that Dayton or Ogden is to go out, unless the former can be promoted; which would remove every difficulty.”[41] For one of these colonels to be promoted, Maxwell would have to go.

The exact cause of the worsening relations between Maxwell and his officers is unknown. The following excerpts from correspondence written between officers shed light on the difficult position Maxwell faced. Lt. Col. Francis Barber wrote to Col. Elias Dayton, his brother-in-law,[42] “Matters with Gen. M.ll are come to a crisis; what will be the consequence I know not; we have persuaded him to resign & assured him at the same time that if he declines the measure, we must submit his conduct to the Judgement of a Court Martial.”[43] The conduct Barber references could be Maxwell’s drinking, which had already resulted in his earlier court martial.

In a letter of July 15, Maxwell wrote to Washington that “my command is disagreeable to the Corps with which I am serving and therefore must beg a removal or permission to retire from the service.” He followed this letter with one on the 20th, in which he stated “I would much rather chuse to withdraw from a service I am fond of, than to remain, where my services could not be made agreeable to my wishes. I therefore request that my Resignation may be accepted.”[44]

While Maxwell awaited a reply from Washington regarding his resignation, his officers quickly shared the news within their close-knit circle. Lt. Col. Barber again wrote to Col. Elias Dayton

The matter between G Maxwell and his officers has at length after much Treaty and Conference come to this conclusion. The Genl. has sent in his Resignation officially, and the officers have agreed not only to be tender of his character, but to endeavor to check any disadvantageous reports that may circulate respecting him. I think upon the whole the affair well settled. The General yesterday morning delivered his excellency his request in writing to resign, which is now on its way to Congress. Last evening he made a formal surrender of his Command in the Brigade to Col. Shrieve in presence of all the field officers.[45]

Col. Matthias Ogden wrote to Dayton, his father-in-law, that “A little contrary to my expectation General Maxwell has made a lawful tender of his commission which we all believe will be readily accepted.”[46]

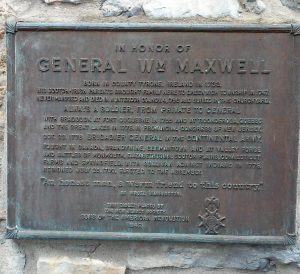

General William Maxwell (Photo by author)

On July 23, Maxwell backtracked after further consideration and described his resignation as “premature as by it I eventually subscribe to the Justice of the allegations of my accusers – I therefore entreat that if your Excellency has not forwarded my request to Congress that You would be pleased to permit me to withdraw it.”[47] Maxwell likely feared it would be dishonorable to resign without facing a court martial to clear his name.

Washington replied that he had in fact transmitted a copy of Maxwell’s resignation letter to Congress, “This being the case I can have no objection to your going to Philada as you request.”[48] In his letter to Congress relating Maxwell’s request to resign, Washington describes Maxwell as “an honest man, a warm friend to his country, and firmly attached to her interests.”[49] Washington added, “In this view and from the length of time he has been in service, the decided part he took at the commencement of the controversy, I would take the liberty to observe I think his claim to such compensation, as may be made to Other Officers of his standing to the present time, only equitable; and hope that it will be considered in this light by Congress.”[50] Congress, unfortunately, accepted Maxwell’s resignation on July 25 and thus, suddenly, ended his military career.

Maxwell, like many Continental Army officers, struggled with debts incurred in the service of his country. He sought Washington’s help and hoped “the time is now come, when full restitution can be made.”[51] Maxwell retired to his farm in Sussex County and served one term in the state legislature. He died on November 4, 1796 after a brief illness and is buried in the Old Greenwich Presbyterian Cemetery in Stewartsville, New Jersey.

A plaque at Old Greenwich Presbyterian Church, honoring General Maxwell, reads in part: “Always a Soldier, From Private to General.”

[1] Harry M. Ward, General William Maxwell and the New Jersey Continentals (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997), 34.

[2] Memorial of Colonel William Maxwell to the Continental Congress, American Archives, Northern Illinois University, accessed March 30, 2016, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A78924.

[3] Ibid.

[4] George Washington to Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, December 8, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 6, 2016.

[5] Washington to Maxwell, December 28, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 6, 2016.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Orders to Maxwell, December 21, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 6, 2016.

[8] Joseph G. Bilby and Katherine Bilby Jenkins, Monmouth Court House: The Battle that Made the American Army (Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2010), 16.

[9] David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 357.

[10] Bilby and Jenkins, Monmouth Court House, 26.

[11] General Orders, November 4, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 6, 2016.

[12] Ward, General William Maxwell, 73.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Testimonial of the officers of the four New Jersey regiments, March 8, 1778, The Papers of the Continental Congress 1774‑1789, National Archives Microfilm Publications M247 (Washington, DC, 1958), reel 51, 177-178.

[15] John Sullivan, Maxwell, and Anthony Wayne to Washington, November 23, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 6, 2016.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Washington to Maxwell, May 7, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 18, 2016.

[18] Washington to Maxwell, May 25, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 18, 2016.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Washington to Maxwell, June 24, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 18, 2016.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bilby and Jenkins, Monmouth Court House, 221.

[23] Washington to Maxwell, December 21, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 20, 2016.

[24] Washington to Maxwell, May 7, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 20, 2016.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Jonathan Forman to Washington, May 8, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Lord Stirling to Washington, May 10, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

[29] Washington to Maxwell, May 10, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Washington wrote Sullivan on May 4, stating that a regiment from Maxwell’s brigade would proceed to Easton, Pennsylvania in a few days. See Washington to Sullivan, May 4, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 29, 2016.

[32] See Washington to Sullivan, May 24, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 29, 2016.

[33] Washington to Sullivan, May 31, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 29, 2016.

[34] Ibid.

[35] For an account of the battle and Maxwell’s participation, see: Sullivan to Washington, August 30, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 29, 2016.

[36] Ward, General William Maxwell, 151.

[37] General Orders, June 22, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 24, 2016.

[38] Jared Sparks, The Writings of George Washington, Vol. VII, (Boston: Russell, Odiorne, and Metcalf, and Hilliard, Gray, and Co, 1835), 76.

[39]Ibid, 83.

[40]Ibid, 86.

[41] Ward, General William Maxwell, 163.

[42] Most of Maxwell’s top officers were from Elizabethtown and had kinship ties. Of the four colonels, only Israel Shreve, a farmer from Gloucester County, did not fit this category. Col. Matthias Ogden, one of Robert Ogden’s twenty-two children, married Col. Elias Dayton’s daughter, Hannah, and Dayton and Col. Oliver Spencer each wedded a sister of Matthias Ogden. Lt. Col. Francis Barber also married a sister of Matthias Ogden, Mary, and as his second wife, was her cousin, Anne Ogden. Aaron Ogden, a brother of Matthias Ogden, served as Maxwell’s aide-de-camp and brigade major. Maxwell found himself surrounded by officers of a higher class with kinship ties, further complicating his command. Ward, General William Maxwell, 163.

[43] Ibid, 164-165.

[44] Maxwell to Washington, July 20, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

[45] Henry Dusenberry Maxwell, Historical Papers Read Before the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey July Fourth, 1900 (New York: Collins & Day, 1900), 7.

[46] Matthias Ogden to Elias Dayton, July 21, 1780, Matthias Ogden Papers, New Jersey Historical Society.

[47] Maxwell to Washington, July 23, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

[48] Washington to Maxwell, July 23, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

[49] Sparks, The Writings of George Washington, 115.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Maxwell to Washington, February 28, 1782, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed May 2, 2016.

One thought on “William Maxwell, New Jersey’s Hard Fighting General”

Thank you for a great article. Being from NJ, it is good to see something written about a general that doesn’t get enough attention for his accomplishments. My question is why isn’t Maxwell not more well known?

Thank you

John Resto