George Washington wrote “no event was ever received with a more heart felt joy” after hearing about the official alliance between the fledgling United States and the world power France.[1] It’s well established that foreign aid both before and after 1778 was crucial to America’s struggle for independence: not only did the French and other European powers supply arms and ammunition to the American cause, but they also expanded the theaters of war against the British Empire. In these theaters, the conflict was complicated and amplified to the point that the British ultimately had to concede defeat in North America. Nowhere was Britain’s struggle more obvious and more significant than in India.

In this theater, in which the British East Company faced off against the Kingdom of Mysore in South India, the British Empire faced challenges that might sound familiar to anyone in the modern West: an opponent under an Islamic regime, a corporation ‘too big to fail,’ a question of grand strategy. The British of course had a large stake in America, but it was these challenges that made British officials rethink what they wanted their empire to look like—and whether it was worth fighting for the American colonies.

The War was Global

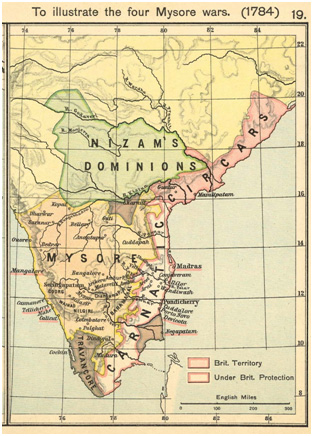

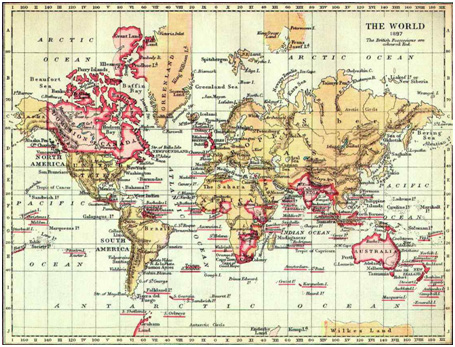

When France joined the war, the war took on international dimensions with significant consequences. Though France by and large contributed the most aid to the rebellious colonists, Spain and the Netherlands also entered the war against Britain. In addition, the League of Armed Neutrality, which included the Russian and Ottoman Empires, took a stand against Britain’s hindrance of shipping. But there were even greater problems than Europe for King George to consider. There was fighting in the Caribbean and the Gulf Coast. And finally, there was India, which was not yet under the direct control of the British crown. The East India Company’s forces had had some successes against various kingdoms in India and held some territory on the subcontinent. But in 1780, they ran into trouble.

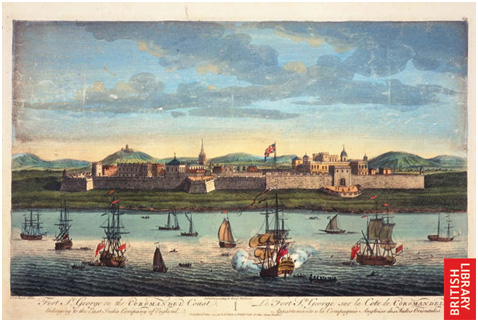

That year, the ruler of Mysore, Hyder Ali, decided to intervene against his rival in the region. The British had captured a French port that Hyder claimed to be under his protection. He marched thousands of troops across the Western Ghats, bound for the important British base of Fort St. George, near the port town of Madras (modern-day Chennai). From the outset the British knew to take the threat of Hyder seriously; this was actually their second war. Hyder had beaten the East India Company badly in the 1760s, and the Company had sued for peace when Madras, their only holding in South India, was threatened.[2] And now, it was threatened again.

Who was America’s “Ally”?

The city of Mysore (also known as Mysuru) lies about 150 km west of the modern-day tech hub of Bangalore (Bengaluru). By the time of Hyder’s wars with the British, it had existed as a distinct kingdom for centuries. However, Hyder was a different kind of leader for Mysore. In the words of Eliza Fay, an English traveler whom he imprisoned, “having acquired by his genius and intrepidity everything that he enjoys, he makes his name both feared and respected; so that nobody chooses to quarrel with him … a man who can neither write nor read.”[3] Though he was illiterate, Hyder earned his reputation as a military strategist. His forces pioneered the use of rockets during his first war against the British, which terrified their soldiers. Anyone generally familiar with the orderly, close formations typical of the era can see why rocket attacks would be particularly devastating. In response, the British eventually developed the Congreve rocket, which is famously referenced in the United States National Anthem (“and the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air”).

Hyder, as well as his son Tipu Sultan, was also problematic for his people. He favored scorched earth policy on the land between his kingdom and the British; when the civilians living there refused to leave, he ordered them mutilated. Eliza Fay was short on kind words for him: “[Hyder] even advised his General, who is Governor of this Province, to massacre all the natives by way of quelling a rebellion which had arisen … In short a volume would not contain half the enormities perpetrated by this disgrace to human nature.” (It’s worth noting that Eliza Fay was a well-traveled woman, and had likely seen her fair share of violent rulers.)[4] Hyder was not even the legitimate ruler of Mysore; that title belonged to the Wodeyar dynasty, whose heirs were now just puppets of the regime. Hyder served prominently in the Wodeyar king’s army before usurping the throne.

It’s important not to ignore the religious tension underlying opposition to Hyder Ali, a Muslim. Historically, India has been home to conflict between Hindus and Muslims, and Mysore was little different, where many Hindus were appalled and angry to be ruled by Muslims. That opposition only grew after Tipu took over as ruler, when the typical punishment for rebelling Hindus was forced conversion to Islam.[5]

Like in the American theater, a quick conclusion proved elusive. In 1780, Hyder defeated the British again and again; in 1781, he was more often on the retreat. Meanwhile, the French aided Hyder at sea, with a fleet led by the Admiral Pierre Andre de Suffren, and on land, with mercenaries in the Mysore army. Hyder was very much aware of the global context of his struggle; in a memo to his son, he said “the English are today all powerful in India. It is necessary to weaken them by war … Put the nations of Europe one against the other. It is by the aid of the French that you could conquer the British armies which are better trained than the Indian.”[6]

There was awareness of a common struggle in America. The flagship of the Continental fleet that defeated a stronger British force at Delaware Bay in 1782 was named the Hyder Ally.[7] On top of that, there’s evidence Mysore reached out to America. According to records of his correspondence, Tipu Sultan sent a letter to the Continental Congress after the Declaration of Independence, proclaiming that “every blow that is struck in the cause of American liberty throughout the world, in France, India, and elsewhere and so long as a single insolent savage tyrant remains the struggle shall continue.”[8]

The Megacorporation

The same East India Company primarily responsible for the Tea Act controversial in America was now locked in a war with this Hyder Ali. The British government did not directly control the Company, but it had a great stake in its success (as evidenced, for one, by Parliament’s passage of the Tea Act). Trade was of course a big motivation for the expansion and defense of European empires—twenty percent of Britain’s imports in 1784 were from India.[9]

But the importance of the Company goes much deeper. In the early 1770s, the bubble in the Company’s stock burst, and at the same time it had 1.5 million pounds in debt and 1 million pounds in unpaid taxes[10]—roughly a tenth of annual government revenues.[11] The Company needed a bailout; in 1773, the British crown agreed to loan it a whopping 1 million pounds. In addition, the government tried to sell off its ‘liquid’ assets: unsold tea, which was shipped to the American colonies. In some part, the Boston Tea Party was a response to the East India Company’s bailout package.

And though Edmund Burke said the Company would “drag [the government] down into an unfathomable abyss,”[12] the government had little choice: the Company, which whose profits alone contributed nearly one percent of the nation’s GDP,[13] was too big to fail. The British hadn’t forgotten that the spectacular collapse of the South Seas Company in the 1720s, another financial bubble, ravaged their country’s economy.

So though the American colonies were important to the empire (and especially the king), the British had a lot to lose if the East India Company failed. Parliament established a board in 1773 to oversee the Company’s activities in India, but it failed to keep the business from falling into even more financial trouble. From 1769 to 1784, when the second war with Mysore ended, the Company’s share price tumbled 55 percent.[14] The Company’s struggle to stay afloat financially and to stop Hyder Ali left the British in doubt of their future in India.

Britain’s “Pivot to Asia”

Just as America today assesses its role in the world, the British had to consider grand strategy. Since de Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope, Europeans had raced to find the fastest, most efficient ways to exploit the goods of India—and there was no easier way than directly controlling the territory. So India, as well as China, drifted closer and closer to the center of Britain’s colonial vision.

Consider the economics of Britain’s calculus. The raw goods to manufactured goods trade with the American colonies was profitable (North America accounted for thirty percent of English exports[15]), but it didn’t compare with the potential for gains in the East. Defending America had gotten expensive, as the Seven Years’ War showed, and the colonists were evidently unhappy to pay for that defense. In contrast, the colonial government in India made substantial revenue from taxes on Indians, and the goods traded, including but hardly limited to spices, were valuable. England was undergoing the agricultural and then the industrial revolutions; a growing market to sell goods was not overseas but right at home. This de-emphasized the market for exports, America, in favor of the source of imports, Asia.

Then there were the challenges on the battlefield. Initially, the British were overconfident in their position; in 1780, the Governor of Madras, Thomas Rumbold, left for England, assured that peace would last at least through the year. The Company was thrown off balance when Hyder started war. French involvement was a problem, too—though the French had been thrown out of North America with the 1763 Treaty of Paris, they were still a threat in South Asia. The British were well aware it was French policy to maintain relations with and support any local powers opposed to the Company.[16] Whether the threat was realistic or not, surely more than one British official lost sleep over being pushed out of India by the French.

So Britain dedicated the appropriate resources. Around twenty percent of Britain’s ships of the line,[17] the workhorses of its renowned navy, fought in the South Asian theater against Admiral de Suffren, a campaign the British could not even win. Importantly, the Royal Navy was also unable to prevent the French from blockading and bombarding Yorktown, which signaled the end of the American theater and ultimately ended the war. Diversion of resources to India prevented the British from making a stronger response to the French-American campaign.

But it was India that demanded Britain’s attention. When word of war with Hyder reached London in 1781, it was inconvenient for the East India Company, which was in the middle of negotiations for renewing its charter with the government. For its part, the government was under public pressure over the war in America that was not going well, and the Mysore war was a reminder of the Company’s incompetence. As a result, Lord North demanded a large annual payment from the Company.[18] In other words, the British government was beginning to see the need for a more direct approach to administration in India—steps toward establishing a new colony.

And that colony was especially important to the British. In the midst of the conflict with Hyder, the Fort William Council, which oversaw all British holdings in India, asserted that “the object that is at stake is the preservation of India to Great Britain and those consequent advantages which the Asiatic dominions of the State may hereafter be capacitated to refund for the relief of the whole Empire.”[19] If Britain were to push its empire to new heights in Asia, it had to prevail against Mysore. For that to happen, Britain had to end its war with France, and thus America, and abandon its control of the Thirteen Colonies.

Conclusion

The war in America came to a resolution of independence, but the conflict with Mysore was far from settled. When word reached Tipu Sultan that France had made peace with Britain, he decided to turn the stalemate on the battlefield into an end to hostilities in 1784. The British were humiliated but not finished—they fought two more wars with Mysore. Though he wanted to join Napoleon’s French Empire, Tipu Sultan was killed by a force led by the Duke of Wellington in 1799, which effectively ended resistance to British rule in South India.

The throne was returned to the Wodeyars, who had petitioned the British for help, and they ruled (under the Raj) until Indian independence in 1947.[20] Tipu, and to a lesser extent Hyder, remains a divisive figure in modern Indian society, seen as both an early, forward-looking Indian freedom fighter and an atrocity-committing Islamic fanatic.

Regardless, he was consequential in America’s struggle for independence, and though the British ultimately defeated him, by then the damage was done. America was a new, separate country.

All this is not to take away from the victory that the American colonists (and their French friends) won for themselves. The siege at Yorktown and French victories in the valuable West Indies colonies were likely at least as influential in bringing the British to the negotiating table. But if anything can be taken away from this, it’s the overwhelming connectedness of the world, even over two centuries before the Internet. A rebellion that began in America led to a renewed conflict for regional hegemony in South India and shaped the future of British colonialism.

And that Second British Empire, in turn, shaped the world. G.J. Bryant notes in The Emergence of British Power in India that once the British established solid footing for possessions like Madras, the Empire had a strategic base to dominate trade in the East and establish new settlements in Australasia. In the nineteenth century, the British controlled all of India, the Raj, and to protect the “Crown Jewel” it would try to create buffer states in Afghanistan and Persia against Russia, and in Siam (modern Thailand) against French Indochina (Vietnam).[21]

One legacy of British conquest and protection of India was the Empire’s meddling in the affairs of these neighboring countries. It would not be a stretch to say that in the British turning their attention in the late 1700s to India we can find some roots of the Iranian Revolution and the modern war in Afghanistan. When we understand the global nature of the American Revolution and the transformation of the British Empire, we don’t just paint a more complete picture of America’s origins, but of America’s challenges abroad, too.

And in the late eighteenth century, it was the British Empire surveying the world map and determining what was feasible, based on the challenges of a fearsome opponent on the battlefield, a bloated but systemically important corporation, and a shift in the relative importance of regions. That whittled away support for a war in America, and the fulfillment of the Declaration of Independence is owed in at least some part to the struggle between a couple of Muslim warrior-rulers and one of history’s biggest corporations, halfway around the world.

[1] George Washington, “George Washington to Continental Congress, May 1, 1778,” ed. John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1931), accessed March 1, 2015, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mgw:@field(DOCID+@lit(gw110323)).

[2] G.J. Bryant, The Emergence of British Power in India, 1600-1784: A Grand Strategic Interpretation (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2013), 294.

[3] Eliza Fay, Original Letters from India, ed. E.M. Forster (New York: New York Review of Books, 2010), 137.

[5] Roy Kaushik, War, Culture, and Society in Early Modern South Asia (New York: Routledge, 2011), 73.

[6] Kaushik, War, Culture, and Society, 86.

[7] Charles W. Goldsborough,The United States’ Naval Chronicle (Washington, D.C.: James Wilson, 1824), 30-31, accessed March 15, 2015, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_United_States_Naval_Chronicle.html?id=a7EtAAAAYAAJ.

[8] Kabir Kausir, Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultand (New Delhi: Light and Life Publishers, 1980), 306.

[9] H.V. Bowen, Elizabeth Mancke, and John G. Reid, Britain’s Oceanic Empire: Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds, c. 1550-1850 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 61.

[10] William Dalrymple, “The East India Company: The original corporate raiders,” The Guardian, March 4, 2015, accessed March 1, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders.

[11] B. R. Mitchell, British Historical Statistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 581.

[12] Dalrymple, “The East India Company.”

[13] Nick Robins, The Corporation That Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational (Ann Arbor: Pluto Press, 2006), 136. This calculation is based on a 17 percent annual profit on trade totaling 200 million pounds in the second half of the eighteenth century (Robins); national income for the United Kingdom in 1780, at 140 million pounds, is derived from “Three centuries of macroeconomic data,” Bank of England, accessed March 30, 2016, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Pages/onebank/threecenturies.aspx.

[15] D.N. McCloskey and R.P. Thomas, “Overseas trade and empire 1700-1860,” vol. 1 of The Economic History of Britain, 1700-Present, ed. Roderick Floud and D.N. McCloskey (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 91.

[16] Bryant, Emergence of British Power, 289.

[17] Jonathan Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 110; also Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence (Cambridge: University Press, 1913), 200-209.

[18] Robins, Corporation, 125.

[19] “Mahratta Peace,” letter from Fort William to Select Committee at Bombay, An Authentic Copy of the Correspondence in India: Between the Country Powers and the Honourable the East-India Company’s Servants, vol. 6 (London: J. Debrett, opposite Burlington House, Piccadilly, 1787), 208, accessed March 1, 2015, https://books.google.com/books?id=PnEIAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

3 Comments

Perhaps this question is not completely whimsical: The British obviously wanted to win the war in North America, but did they actually try hard to win?

I think, for starters, the sugar islands always were more important than the mainland colonies.

Great overview of the war in India.

Two observations based on the research for my book “After Yorktown” (Westholme Publishing, 2015), which goes into greater depth about Hyder Ali.

The illustrations of Hyder shown here are fanciful representations. In truth, Hyder was hairless—including shaving or plucking his eyebrows—because, he once said, he didn’t want anyone in his realm to look like him. I’ve posted a more accurate picture (albeit with eyebrows) on my website: http://www.donglickstein.com/portraits/#hyder

Also, for the record, the last battle of the American Revolution wasn’t the naval Battle of Cuddalore fought by Hughes and Suffren on June 20, 1783; it was an unsuccessful sortie by the French against British land lines in the wee hours of June 25.

Thank you Richard for the excellent and informative information on Haider Ali. However, I would like to know whether Haider Ali, as an ally to the US and GW, supported the revolutionary efforts by promising military aid to the US by sending three ships to aid in the Independence Movement?