Denouncing the reputation of Benedict Arnold began immediately after he fled West Point and returned his allegiance to the British empire on September 25, 1780. Without hesitation, contemporaries denounced him as a nefarious human being, a devious villain suddenly well-known to everyone for his “barbarity,” “avarice,” “ingratitude,” and “hypocrisy,” in sum nothing more than “a mean toad eater.” Stated General Nathanael Greene a week after Arnold’s apostasy: “Never since the fall of Lucifer has a fall equaled his.”

Since 1780, why Arnold committed treason has remained the focal point of interest about this general officer whom Washington once held high as his best fighting general. Was it insatiable greed, his beguiling second wife Peggy, or Satan himself that provoked Arnold’s apostasy? Forgotten in these explorations and denunciations about his allegedly corrupt character is the reason why Arnold’s contemporaries were so upset about his apparent treachery: Arnold’s natural military genius in support of the Revolution.

Born in January 1741, Benedict Arnold grew up in Norwich, Connecticut, before establishing himself as an apothecary and sea going trading merchant in New Haven. His biggest childhood challenge involved a family crisis that started when a diphtheria epidemic struck his community. His father nearly died, and he lost two of his younger sisters. His father, also named Benedict, once a respected carrying merchant, began to lose his way after seeing his family devastated. He took to drink, became an alcoholic, and eventually succumbed to acute alcoholism.

As the sole surviving son, young Arnold had to step forward as a surrogate head of household, which fits with his only description of himself as a teenager. He portrayed himself as “a coward until he was fifteen years of age” and noted that his adult reputation for “courage” was an “acquired” trait. He was not the little hellion of fictional old wives’ tales about his presumed dissolute youth, rather a lad who had to grow up quickly to help take care of his mother and surviving sister Hannah.

His mother, also named Hannah, secured an apprenticeship for him with her cousins, Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, who taught him the apothecary’s trade. During these apprenticed years, the French and Indian War was engulfing the colonies. One set of misleading stories had young Benedict repeatedly enlisting in New York regiments, only to grab bounty money and desert, thereby demonstrating his self-serving, avaricious nature. Apparently, the Lathrop brothers never missed him, even when he was gone for weeks at a time.

In actuality, Arnold’s lone military experience before 1775 was about two to three weeks of militia duty in 1757 when French and Indian forces captured and destroyed Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George. The Norwich militia unit he joined returned home when the French force withdrew north rather than invading New England.

Benedict Arnold, in sum, entered adulthood with no meaningful military training or experience, unless one counts parading around as a lowly private on militia muster days. At the outset of the Revolutionary War in April 1775, he was at best a military novice, a true amateur in arms. Yet within two years, Arnold had emerged as one of George Washington’s most invaluable generals. Nathanael Greene found no hint of Lucifer in Arnold when he described him in late 1776 as “a fine spirited fellow, and active general.” Nor did Washington foresee problems when he wrote in 1777 that “surely a more active, a more spirited, and sensible officer, fills no department” of the Continental army.

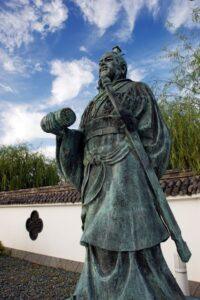

What was it about Arnold, then, that made him so useful a leader in the pre-treason eyes of Greene and Washington, among many others? Whether in his business dealings or in military operations, Arnold repeatedly demonstrated the inborn capacity to think in broad strategic terms while drawing upon tactical options that would ultimately yield positive results. At times, Arnold seemed to be channeling the precepts of the ancient Chinese military thinker Sun Tzu, sometimes rendered Sun Wu, in his classic volume entitled The Art of War. In other situations, the ideas of Sun Tzu would have been too constraining for the martial challenges Arnold faced. Regardless, his capacity to act decisively with well-reasoned boldness, with a fiery temperament thrown in, was Arnold’s bountiful gift to the cause of American liberty during the initial phases of Revolutionary War.

When Arnold first opened his apothecary’s store in New Haven in the 1760s, he offered a variety of books for sale, including some military tracts. Even if he perused such volumes, his military acumen could not have radiated back to the Sun Tzu’s teachings. The first modern translation of The Art of War appeared in the French language during the early 1770s. Apparently no English translation existed until the early twentieth century. Arnold, by his own temperament and instincts, as well as determination and vision, was actually his own teacher. In his seagoing trading ventures to the West Indies and Canada, he often served as the captain of his own vessels. He learned how to handle crews of mariners to get the best efforts from them in daily challenges. No evidence exists that he treated them harshly, rather that he was able to gain their respect by his even-handed leadership.

By 1774, Arnold could smell a civil war brewing within the British empire. An enthusiastic advocate of defending American rights, he organized some sixty-five New Havenites, including a few Yale College students, into what the Connecticut government recognized as the Governor’s 2nd Company of Footguards in March 1775. Serving as the elected captain, Arnold prepared to lead the Footguards to the Boston area after learning about the battles of Lexington and Concord. The Footguards had uniforms, paid for by their captain, but they lacked muskets, power, and ball. These martial necessities were available in New Haven’s powder magazine. The cautious town fathers, fearing the spread of a shooting rebellion, refused them entrance. Arnold gave them a few minutes to rethink matters, then informed them that his company would force its way into the magazine unless the keys were forthcoming. Thoroughly intimidated by Arnold’s threat, they finally handed over the keys, thereby avoiding a nastier confrontation.

Within a few days, the well-armed Footguards arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where thousands of New Englanders were gathering to pin down Gen. Thomas Gage and his redcoats in Boston. Arnold, for his part, met with such local rebel leaders as Dr. Joseph Warren and spoke of the need to capture the valuable cache of artillery pieces at Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point on Lake Champlain. In desperate need of such weaponry to help contend with possible British breakouts of Boston, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety gave Arnold a colonel’s commission. His orders were to hasten west, recruit a regiment, and seize lightly defended Fort Ti, which he described as in “ruinous condition,” so bad that it “could not hold out an hour against a vigorous onset.”

Taking the fort was not a problem, but contending with Vermont’s Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys proved a vexing challenge. Allen and the Boys, operating under apparent authority from Connecticut, were already in position to take Fort Ti when Arnold caught up with them on the east bank of Lake Champlain. Arnold displayed his commission, but the Boys, a roughhewn lot, laughed at him. Allen was their leader, and they would follow no other, especially since Arnold had no troops with him. Finally, after some shrewd negotiating on Arnold’s part, Allen agreed to a joint command. Under cover of darkness, the two of them led a party of Green Mountain Boys across the lake and easily captured the fort with nary a lost life on May 10, 1775.

Too often, through the prism of treason, Arnold has been portrayed as an impulsive, needlessly confrontational military leader. In reality, he was often a master of patience and restraint, concentrating on the goals he wanted to achieve. Such was the case with Allen and the Boys. To him, they were not exactly enthusiastic patriots determined to secure valuable ordnance pieces for the cause of liberty. Rather, he viewed them as frontier ruffians mostly interested in plundering whatever goods they could find in the fort.

Once inside, the Boys rejoiced when they discovered ninety gallons of rum. Getting roaring drunk, they repeatedly belittled Arnold; and two of them apparently took pot shots at him. Still, these “wild people,” as he called them, did not intimidate Arnold. Showing impressive forbearance, as he so often did during his military career, he kept his fiery temperament in check and waited out the Boys until they drifted back across the lake to Vermont territory with various forms of plunder in hand.

Arnold had shown wisdom in his dealings with Allen and the Boys, a key characteristic for successful commanders according to Sun Tzu. He had not let personal differences and insults divert him from the mission of gaining access to the much needed military ordnance. Once in charge, Arnold focused on pulling together his own regiment at Fort Ti. Tearing off his cautionary mask, he did something else that Sun Tzu would have commended. He went on the offensive and attacked when the enemy was not expecting a quick-hitting strike.

Concerned about a possible British counter stroke coming out of Canada to retake the fort, Arnold seized the initiative. In mid-May he led a small force north down Lake Champlain and twenty-five miles into Canada. They struck the British stronghold of St. Johns, completely surprising a handful of defenders there. He and his raiders seized small weapons and two 6-pounder cannons, destroyed any small craft they could find, and sailed away in a British sloop later named the Enterprise.

By this one aggressive stroke, Arnold had taken command of the lake. Nearly a year and a half would go by before the British attempted an invasion of their own out of Canada. As for Arnold, after many more adventures, he would be waiting to greet them, this time as the commodore of the hastily assembled rebel fleet on Lake Champlain.

In mid-June 1775, Arnold sent a letter to the Continental Congress in which he advocated the movement of a large patriot force into Canada to seize and secure Quebec Province as the fourteenth colony in rebellion. Why? Having sailed his own trading vessels into such Canadian ports as Quebec and Montreal, he understood the terrain. He could envision what would become British strategy in 1776: to surround New England and cut off the head of the rebellion. The British, as they would do, deployed masses of troops to New York City and Quebec Province in an effort to take control of the Lake Champlain/Hudson River corridor. Having cut off New England from the rest of the colonies, these forces were to sweep eastward while Royal Naval warships put pressure on such key port towns as Boston on the Atlantic Ocean side.

In his letter, Arnold stressed the need to “frustrate” a major portion of Britain’s “cruel and unjust plan of operation” to squeeze life out of the rebellion in New England by sending one invading force south through Canada. Seizing Quebec Province would disrupt that move while also assuring “a free government” there fully dedicated to liberty. Furthermore, Canada could serve as “an inexhaustible granary in case we are reduced to want,” should a long-term war eventuate. Arnold closed by laying out an operational plan to invade Quebec Province “without loss of time.” He offered to take command of his proposed expeditionary force, confident that “the smiles of heaven” would soon be blessing the patriot cause.

Arnold instinctively appreciated the strategic maxim of Sun Tzu: “Thus the highest form of generalship is to balk the enemy’s plans.” Attack yes, Congress soon concluded, but not with the likes of Arnold in command, not initially. Congress was an unabashed political body, and Arnold had few insider connections. Further, the Massachusetts rebels, complaining of the costs they were mostly bearing in standing up to the British around Boston, got Connecticut to agree to pick up the expense tab in the Champlain region. Despite his highly meritorious effort there, Arnold found himself dumped from command after Connecticut agreed to send troops to garrison Fort Ti and Crown Point under well-connected but uninspiring Col. Benjamin Hinman.

As events played themselves out, overall command of the invasion through Lake Champlain would go to Congress’s designated Northern Department commander, wealthy Philip Schuyler of New York. He rated Arnold’s performance at Fort Ti and Crown Point as fully meritorious. In August 1775 Schuyler and others brought Arnold to George Washington’s attention. His Excellency had recently taken command of rebel forces encircling Boston. Meeting with Arnold, he too saw merit in the energetic patriot and the ideas he was sharing.

Arnold accepted Washington’s offer of a Continental colonel’s commission with the assignment to lead one of two patriot forces into Canada. Thus began a martial adventure that would culminate with the defeat and surrender of Gen. John Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga in October 1777. One detachment under Schuyler, who fell ill and turned the command over to Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery, headed north down Lake Champlain and captured Montreal in mid-November. Arnold’s column, meanwhile, struggled through the backwoods of Maine and, after much suffering, reached the Plains of Abraham outside the injudicious city of Quebec, also in mid-November. Arnold’s personal stamina and boundless energy during this death-defying trek through the wilderness earned him the epithet “America’s Hannibal” and a brigadier generalship awarded him by Congress.

The two detachments rallied together as one before Quebec City in December but failed to gain a victory in a desperate attempt to breach the city’s gates under cover of a driving blizzard on the last day of 1775. The plan of attack, Arnold knew, was impetuous and born of desperation, not the kind Sun Tzu would have approved for a military force much weaker than Quebec’s defenders. Reality, however, dictated ill-advised action, since the enlistment periods of patriot soldiers were over at the end of that day. Arnold and Montgomery felt they had no choice but to attack before some portion of their force disappeared into the woods and returned to New England.

Montgomery, heading one column, was killed instantly from a cannon blast; Arnold, heading a second, sustained a nasty wound to his left leg that knocked him out of the assault. Before the fighting was over, dozens of patriots lay dead or wounded with over 400 taken prisoner by the defending British forces under the command of Gov. Guy Carleton.

What was amazing was that Arnold refused to quit. As his badly wounded leg began to heal, he drew on his boundless energy to maintain a paper siege of sorts around Quebec City with the few troops he had left. He spent the winter season, as he wrote, laboring “under almost as many difficulties as the Israelites of old, obliged to make brick without straw.” Arnold drew up plans to break into the walled city but lacked the necessary resources to do so. In the end, despite an ennobling effort by Congress to send more troops to Canada, Quebec Province could not be held. As British strategy dictated, British and Hessian reinforcements began arriving at Quebec City during May 1776. By late June, they had driven the whole of patriot forces, now riddled with smallpox and other diseases, all the way back to Fort Ticonderoga.

Typical of his fighting character, Arnold was among the last rebels to leave Canadian soil. He was among the first to think through operational plans to block the British military invasion that was sure to come out of Quebec Province. By June 1776 a massive British land and sea invasion of the rebellious colonies was under way. Given the limited size of most eighteenth-century military forces, British numbers, including Hessians, were impressive. By early August some 45,000 soldiers and sailors were getting into position to capture and establish New York City as their main base of operations; another 8,000 were preparing to move out of Canada and crush patriot resisters in the northern theater. By mid-summer, Governor Carleton, with John Burgoyne serving as his second in command, was assembling a flotilla of vessels to move south with his army in tow across Lake Champlain.

From Arnold’s perspective, the key step was to block or, better yet, drive Carleton’s advancing force back into Canada. In doing so, he worked closely with Northern Department commander Philip Schuyler and former British field grade officer Horatio Gates, now a major general in the Continental army. Schuyler would operate as the key supply officer, and Gates would take charge of strengthening the rebel defensive line at Fort Ti. As for Arnold, he would demonstrate a kind of versatility never imagined by Sun Tzu. At the request of Schuyler, Arnold agreed to serve as commodore of the rebel fleet being assembled on Lake Champlain, a daunting assignment that involved constructing enough vessels to put on a show of defiance that might frighten off the expected British onslaught.

Readying the fleet was a major undertaking, but by mid-September enough vessels were in the water for Arnold to sail north toward the Canadian border. Nine of the craft were gundalows, really overgrown bateaux. They were flat-bottomed boats, each having a fixed sail and the capacity to carry a crew of up to forty-five men as well as a few ordnance pieces. They could sail with the wind but could not maneuver to the windward, so crew members had to be prepared to pull at oars when needed.

Arnold, for his part, pushed for the construction of row galleys, larger craft featuring two masts rigged with lateen sails that could swivel with the wind. Such rigging gave the row galleys much more maneuverability than the gundalows, regardless of the wind’s direction. In addition, the fleet had a few other craft, including the sloop Enterprise that Arnold had captured when he and his raiders launched their surprise attack on St. John’s back in 1775. Three schooners were also available, including the Royal Savage, captured from the British during Montgomery’s advance into Canada. This vessel served as Arnold’s flagship until three row galleys – the Congress, Trumbull, and Washington – joined the flotilla. Arnold moved over to the Congress and designated this craft his flagship.

Assembling the fleet was one challenge being conquered, given the shortage of skilled ships’ carpenters plus the lack of such essential supplies as cordage, sailcloth, and various kinds of cannon shot. A second was preparing orders to guide Arnold’s actions on the lake. This assignment, wrote Gates, was “momentous” in the critical objective to secure “the northern entrance into this side of the continent.” Arnold was to operate by conducting “defensive war.” He was to take “no wanton risk” with the fleet, yet he was to display his “courage and abilities” in “preventing the enemy’s invasion of our country.” In other words, he was not to conduct such offensive operations as sailing into Canada and attacking the British fleet then being assembled at St. Johns. Rather, he was “to act with such cool, determined valor, as will give them [the enemy] reason to repent their temerity” in their movement up the lake toward the patriot defenders then gathering at Fort Ti.

By any reasonable measure, Arnold had accepted an impossible military assignment, once again not the kind that Sun Tzu would have endorsed. The ancient Chinese strategist had warned about the danger of a smaller force attempting “an obstinate fight” with a larger one, which in the end would result in its being “captured by the larger force.” Arnold knew he was commanding the inferior fleet, made worse by crews of soldiers with no sailing experience. Sun Tzu had declared that “if slightly inferior in numbers, . . . avoid the enemy,” and “if quite unequal in every way, . . . flee from him.” Even on the defensive, Arnold could not flee. His only hope for retarding the British was to innovate, and innovate this natural military genius did.

Sun Tzu had declared that “all warfare is based on deception,” a principle that Arnold instinctively understood. Even before the row galleys were available, he led his less than impressive fleet of about twelve vessels toward Canada, arriving near the border in mid-September. Once there he acted as if he might sail north down the Richelieu River to St. Johns where the British fleet was assembling. In reality, Arnold was just putting on a show with no intention of engaging in offensive operations. Rather, his purpose was to intimidate, if possible, Governor Carleton, who received scouting reports about the fleet’s presence and seemingly readiness for combat.

The ruse worked. Even though the British governor already had Arnold’s fleet outnumbered and outgunned, he hesitated. To assure complete superiority, Carleton refused to let his flotilla proceed south until the final assembly of a sloop of war, the Inflexible, a craft that mounted eighteen 12-pounder cannons and was superior in firepower to any vessel available to Arnold. On October 4, Carleton finally ordered his flotilla to move out. Having noted the presence of the “considerable naval force” waiting to defend Lake Champlain, his objective was to sweep aside that fleet and retake Crown Point and Fort Ticonderoga before early winter weather in this northern clime would halt further operations pointing toward New England.

Sun Tzu had advised to “learn the principle” of an opponent’s capacity for “activity or inactivity.” During the months when Arnold maintained a paper siege of Quebec City, he sized up his chief opponent Carleton as a cautiously calculating leader. The governor would not take unnecessary risks, even when he held the military advantage, unless he was sure he had totally superior military strength. As such, Arnold’s brassy appearance near the Canadian border had caused Carleton to delay three critical weeks, which gave the patriots more time to strengthen defenses at Fort Ti. Pretending he would take aggressive action when committed to defensive maneuvers secured Arnold as a winner of the first round in the game of martial wits.

The Champlain commodore knew something else of critical importance. Despite the pleadings of General Schuyler, Fort Ticonderoga was short on supplies of powder and ball and could not stand up to a sustained British onslaught. As such, the patriot fleet could not just stand by and let Carleton and his minions move easily up the lake without significant resistance. Only a dramatic – and very real – show of force might convince the governor to return to Canada, despite his superior strength. Arnold could count on sixteen vessels, but Carleton had thirty-six, including twenty-eight gunboats, smaller craft that carried one sizable cannon (12 to 24 pounders) each. The British, with 417 artillery pieces, held a more than four-to-one advantage in firepower, since Arnold’s fleet mounted only 91 cannons, including small swivel guns. Just as bad, Arnold’s crews contained few sailors, whereas the British crews were full of experienced mariners.

What Arnold did have was the creative vision and energy to fight Carleton’s fleet to a draw of sorts. Like Sun Tzu, the American commodore realized that understanding “the natural formation of the country is the soldier’s best ally.” Terrain mattered, especially if Arnold could find a location on Lake Champlain that would both surprise the enemy and neutralize Carleton’s crew and firepower advantages. While cruising down lake toward Canada, Arnold had spotted that location, a bay close to the New York shoreline hidden to any fleet moving south. Blocking the view from the lake’s main channel was Valcour Island, which rose to 180 feet in height. The bay itself was a half-mile wide, and by late September Arnold had his fleet nestled together in a half-moon formation, getting ready for combat.

Arnold explained that this defensive battle line would mean that only a “few vessels can attack us at the same time, and those will be exposed to the fire of the whole fleet.” He was correct. On the morning of October 11, 1776, Carleton’s fleet, riding a crisp northerly wind, cruised around the eastern side of Valcour Island intent on reaching Fort Ticonderoga some seventy miles away. About two miles south of the island the British finally spied the waiting Americans, but hauling into the wind broke up the fleet’s formation. What ensued was a battle that fit Arnold’s prediction. The whole of the British flotilla, trying to maneuver against the wind, could not get into an organized battle line. As a result, even though the patriot craft suffered serious damages with many casualties, the Champlain fleet was still functional when nightfall ended the battle.

For his part, Carleton was satisfied with the day’s results. As soon as the wind started blowing from the south, his flotilla could move in and finish off the patriot fleet. Arnold realized the same. Now for all practical purposes trapped in the bay, his vessels were sitting ducks waiting for total obliteration. Up to this point, “the clever combatant” Arnold, in the words of Sun Tzu, had succeeded in imposing “his will on the enemy.” Now the question was whether Arnold possessed the genius to “not allow the enemy’s will to be imposed on him.” What he and his captains observed as night approached was that the British had left a small opening for escape close to the New York shoreline; and escape they did. Taking advantage of a heavy fog, the patriot vessels formed into a single line and used muffled oars to row through that gap. When the fog lifted the next morning, an astonished Carleton could not believe what he beheld. Valcour Bay was empty of American craft.

Now the race up the lake was on. By October 13, the British were starting to overrun the damaged, slow moving American vessels near a land form called Split Rock. Arnold, conscious of munitions shortages at Fort Ti, had to act decisively to slow the enemy advance. He did so in one of the most unheralded fighting moments of the whole Revolutionary War. Aboard the Congress, he issued orders to have his craft turn northward to take on swarming enemy vessels. For something like two hours, he and his crew engaged in close quarter combat with three of Carleton’s vessels having a five-fold advantage in firepower. Soon four more enemy craft joined in the pounding. It was like a fight to death in which one opponent kept landing knockout punches but with no referee calling the ten count. All but completely battered with “the sails, rigging, and hull of the Congress . . . shattered and torn to pieces,” Arnold somehow maneuvered his foundering vessel, along with the four torn up gundalows that he was protecting, into a small bay in Vermont territory where the British could not reach them. Leaving nothing for the enemy, he ordered all five vessels set on fire before he and his crew made their way overland, reaching Fort Ti the next day.

Arnold’s courageously aggressive performance in defending Lake Champlain had significant consequences, both for the Revolution and for himself. Governor Carleton, amazed by the death-defying spirit of Arnold and the patriot fleet, moved his forces up to Crown Point but then hesitated. Burgoyne was ready to take on Fort Ti, but Carleton started to fret about supply lines back to Canada, especially with the winter season looming. In early November, the governor decided to withdraw his whole force back to Canada to wait out the winter before launching another invasion in 1777. Affecting the pullback decision was Arnold’s bravado at the northern end of the lake that delayed the British flotilla from launching its invasion for three critical weeks. Also, the death-defying heroics of Arnold and his patriot fleet had intimidated Carleton. With such fighting prowess displayed by the rebels, certainly a reversal of what the governor had observed earlier that year when patriot forces pulled out of Canada, he was no longer sure he could capture Fort Ticonderoga without grave results, possibly even defeat.

Benedict Arnold’s natural born military brilliance had helped save the patriot cause in the northern theater, at least for another year. Members of the Continental Congress called Arnold a true hero, but demeaning voices were also in play. Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, a former British field-grade officer devoid of martial accomplishments who was then at Ticonderoga, labeled Arnold “our evil genius to the north.” According to Maxwell, Arnold’s “pretty piece of admiralship” had wasted the Champlain fleet. He claimed nothing more than personal aggrandizement had motivated Arnold, just another self-serving showoff who in reality had actually outwitted and disrupted a major part of British military operations in 1776.

Sun Tzu called any general “a heaven-born captain” who could “modify his tactics in relation to his opponent and thereby succeed in winning.” Through deceptive tactics and strategic vision, Arnold lost the fleet but won the northern campaign in 1776. More than a hundred years later, long after the Revolutionary generation was dead and gone, the famous naval historian Capt. Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote in his classic The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783 (1890): “The little American navy on Champlain was wiped out; but never had any force, big or small, lived to better purpose or died more gloriously, for it saved the Lake for that year.”

During 1777 Arnold stepped forward again and provided invaluable service to the American cause. His vision and courage came through dramatically in the defeat and capture of General Burgoyne’s invading army. That, however, is another story. Even before the momentous Saratoga campaign, Benedict Arnold had established himself as Washington’s fighting general and commodore, an amateur in arms but also a natural military genius who tenaciously outwitted superior enemy forces in 1776. That Arnold turned against the cause of liberty he once so enthusiastically embraced was both a shock and an embarrassment to his contemporaries. To preserve the good name of the Revolution, he had to be stripped of his accomplishments and denounced as “a mean toad eater,” misled by greed, Peggy, and the devil, or some depraved combination thereof. As a result, the natural born military genius Benedict Arnold remains to this day an accursed being, likely forever shunned from the pantheon of American heroes.

For additional information about Arnold’s amazing career as a Continental officer, consult James Kirby Martin, Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered (New York, 1997). Various translations of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War have been published over the past century. I used the widely accepted 1910 translation by the sinologist Lionel Giles, available in various editions including one published in 2014 by Black and White Classics. For key primary documents relating to the naval campaign on Lake Champlain in 1776, see William James Morgan, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Vol. 6 (Washington, D. C., 1972). More details may also be found in James L. Nelson, Benedict Arnold’s Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain but Won the American Revolution (Camden, ME, 2006).

3 Comments

Dr. Martin, thank you for a stimulating article that really has me going this morning. I take no issue with your scholarly research regarding Arnold’s military activities. Although as we both know, the precepts written by Sun Tzu are pretty much common sense to anyone trained in military skills. Another obvious example of strategic activities seeming to mirror them is General Nathanael Greene’s Southern Campaign.

It is your comments seeming to excuse, and perhaps this is not the right word, Arnold’s treason that has me commenting. As someone who has studied “spies”, or in this case a :write-in” defector, for over 40 years and has had first hand experience dealing with some, I always get frustrated with shifting the blame away from individual responsibility. Especially so in the case of Arnold. He is, in my opinion, the classic “ego” traitor. He had no ethical or moral basis in his character – it was all about his self image. He is simply a traitor to his country, his army and his political protector, Washington. His willingness to sellout all three is well documented. His military successes, and indeed there is some debate among Military Historians about his skills verse personality leadership, cannot be used to justify or excuse his subsequent actions.

Perhaps the best compromise I would accept in this regard is the “cut off his leg and bury it with honors” old story.

Again, thanks for starting my day on a stimulating note.

Thank you for an interesting article on an interesting man.

There is no question that Arnold was a tenacious warrior, a driven man. However, he had a character flaw and like many men he, in the end, was an opportunist looking out for his personal interests. The ability to subordinate personal interests to the good of the nation and a cause greater than the individual is what separates heroes from men. There is no question his personal actions during the campaigns of 1775, 1776 and 1777 significantly influenced the course of the Revolution. Had Arnold died at the gates of Quebec, on Lake Champlain or on the Saratoga Battlefield, we would classify him an American Revolutionary War hero. Instead he is just another man with a stellar record in combat, a strategic thinker and a flawed character. We see individuals with character flaws all too often. It is rare we see strategic thinkers with stellar combat records that fall from grace as dramatically as Arnold. This is what makes his fall all the more tragic.

MORE INFORMATION ON BENEDICT ARNOLD THAT I HAVE EVER SEEN / MUCH LESS READ OR

STUDIED… WELL WRITTEN – EXCELLENT STORY. H.T.PAISTE,III 08/30/16