An internet search for Conrad Heyer will reveal that he was a Revolutionary War soldier who crossed the Delaware with George Washington. In fact, you’ll find a variation of this sentence repeated on page after page almost word for word: “He served in the Continental Army under George Washington during the Revolutionary War, crossing the Delaware with him and fighting in other major battles.”[1] Everyone, including some usually authoritative sources, apparently copied what someone else had already written without attempting to verify the information.[2]

The reason that Heyer draws so much attention is that he is one of the hundred or so Revolutionary War veterans to have been photographed.[3] By the 1840s, when photography was becoming widely available, veterans of the war were becoming scarce. Heyer, when his picture was taken in 1852, was among the oldest men ever photographed. The daguerreotype image eventually came into the possession of the Maine Historical Society where it remains today.

I recently wrote a book about six Revolutionary War veterans who’d had their pictures taken. The Revolution’s Last Men: The Soldiers Behind the Photographs[4] was originally intended to be a simple update of the 1864 book Last Men of the Revolution[5] which included photographs and biographies of what were believed to be the last six surviving pensioners of the war. As I researched the wartime service of the book’s six subjects, however, I discovered that the book was filled with errors, dramatically overstating the service of some men while omitting significant wartime events in the lives of others. The biographies written in 1864 bear little resemblance to the men’s actual service, determined from documents written much closer to the events including their own pension depositions. And yet, the flawed 1864 biographies, along with copies of the photographs, continue to be circulated and accepted without question.

Because I showed how wrong those six biographies were, people ask me about others. What about Conrad Heyer, who famously crossed the Delaware with Washington? Is anything amiss with his story?

To find out, I started in the same place that I did with the other six pensioners: their own pension depositions. The United States government passed legislation granting pensions to veterans of the Continental Army in 1818. Each applicant had to prove his military service using documents such as discharge papers, testimony of others with whom he had served, or a combination of the two. Most men applied in person at their local courthouse and gave a deposition that was witnessed by a judge or other official. Corroborating depositions by others were also sworn and recorded. Most of these records survive in the United States National Archives, and are readily available on microfilm at research facilities or through subscription internet services.

The purpose of the depositions was to prove service, not to tell war stories, so most of them are brief and focus on dates, titles of military units and names of officers. Because the first depositions were given thirty-five years after the war ended, and some long after that, discrepancies are common. But the very basic facts of how long a man served, and during what years, are usually not difficult to determine by comparing a deposition to other primary source information.

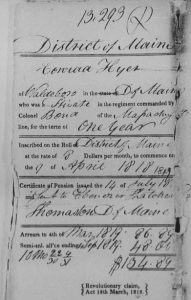

The pension deposition of Conrad Heyer,[6] dictated to a justice of the peace who spelled his name “Hyer” on July 14, 1819, reads:

I Conrad Hyer of Waldoboro in the County of Lincoln & State of Massachusetts testify & declare that about the middle of December AD 1775 I enlisted to serve as a private in the army of the American Revolutionary War in the Massachusetts Line and Continental establishment to serve against the common enemy for the term of one year and that in pursuance of paid inlistment I did actually serve said term of one year in the army aforesaid and the line aforesaid & Continental establishment and against the common enemy; that the first of said year I was under Capt. Fuller in Colonel Bond’s Regiment, but that I was afterwards transferr’d to Captain Smith’s company in said Regiment and that after the death of said Colonel Bond the regiment was commanded by Colonel Alden who had the command of the same when I was discharged & that I was then in said Smith’s company. I received my discharge which was an honorable discharge from Captain Agry who gave me a pass in writing including three or four others, but nothing else in writing & said pass is now lost. The place of my discharge was on the North River at Fish Kilns and the time I received it about the middle of December AD 1777. That I never have received any pension under the United States. And I further testify & declare that by reason of my reduced circumstances in life I am in need of subsistence from my country for support & therefore respectfully ask to be placed on the pension list of the United States by virtue of the Act of Congress of March 18 AD 1818, entitled “an Act to provide for certain persons engaged in the land & naval service of the United States in the Revolutionary War.

Conrad Hyer (X his mark)

Nothing about crossing the Delaware, but at a glance it seems plausible if Heyer served until December 1777. Looking more closely, though, there’s an inconsistency: Heyer says that he enlisted in December 1775 and served for just one year. This sort of discrepancy turns up frequently in pension depositions, and can be resolved by learning about the regiment in which Heyer served, a Massachusetts regiment commanded initially by Colonel Bond and then by Colonel Alden. This was the 25th Continental Regiment, raised in January 1776 under Col. William Bond. When he died on August 31, 1776, Lt. Col. Ichabod Alden took over.[7] Company commanders included Capt. Nathan Fuller and Capt. Daniel Egery (spelled Agry in Heyer’s deposition);[8] Lt. Nathan Smith, who started the year in Fuller’s company, was promoted to captain and assumed command of a company on August 31.[9] All of the names given by Heyer, then, match contemporary information about the regiment.

The 25th Continental Regiment marched to the New York City area in April 1776 but was then sent to join the army in Canada. The regiment returned from that difficult campaign and was in Morristown, New Jersey, by November. The organization was disbanded in December 1776, its soldiers discharged from their year-long obligation.[10] Witnesses gave corroborating depositions, also in Heyer’s pension file. Fellow soldier Valentine Mink deposed that he had served in Captain Fuller’s and Captain Smith’s companies, and “that I well knew Conrad Hyer in said service that he enter’d the same with me.” Mink went on to say that Hyer “served from the middle of December AD 1775 to the middle of December AD 1776 at which time he was discharged honorably from said service at Fish Kilns on the North River by a pass in writing sign’d by Captain Agry.” John Vanner, another soldier in the 25th, also “well knew Conrad Hyer” had served “from December AD 1775 to December AD 1776,” and “was honorably discharged at Fish Kilns by a pass from Capt. Agry to himself and several others of whom I was one.” It is clear that Conrad Heyer’s service in the 25th Continental Regiment ended in December 1776, and that it was a slip of the writer’s pen that put the year 1777 in his deposition.

No mention is made of any subsequent army service.[11] It is significant that Heyer was discharged in Fishkill, New York, a place along the Hudson River (called the North River during the American Revolution) in mid-December. Even if he had reenlisted, it is nearly impossible that he could have traveled from Fish Kill to join Washington’s army in Pennsylvania by December 25, in time to participate in the crossing of the Delaware that night.

Conrad Heyer was born in Waldoboro’ (throughout the nineteenth century the name is usually spelled with an apostrophe, although it occasionally appears as Waldoborough), Maine in 1749, the son of German immigrants. At the time of the American Revolution, Maine was not a separate colony but part of Massachusetts, so Heyer was a Massachusetts soldier. He lived for an exceptionally long time, from 1749 until February 1856, all of it in Waldoboro’. His obituary read:

Died, on the 18th inst., at Waldoboro’, Conrad Heyer, at the advanced age of 106 years, 10 months and 9 days. His parents were from Germany, and he was the first child, of the white race, born in that town, in which he always continued to reside. Though of rather slender form, Mr. Heyer had great physical energies, with much power of enduring labor and fatigue. He possessed remarkable health, having never till this winter been confined a day by sickness. Mr. Heyer was from early life a respected and consistent member of the German Lutheran Church. For three years, he served in the war of the Revolution, and was a pensioner. He voted at every Presidential election since the establishment of our National Government. His employment was that of a farmer. For the last ten years, he attracted much attention, many strangers visited him, and always found him a source of much interest, not only as a relic of the past, but for the exactness of his memory, and the very clear accounts he loved to give of early occurrences within his own observation. His maxims of prudence and propriety deduced from his long observation of men, had weight with his neighbors. As he lived with mental powers wonderfully preserved, so he continued to hold the respect of his acquaintances, and the memory of his virtues and of his wisdom will, for a long time, exert useful influences in the circle where he was so well known.[12]

Notice that this memorial says three years of service in the Revolution, even though Heyer himself had claimed only one year when he applied for his pension in 1819.

As indicated in the obituary, by the 1850s Heyer’s advanced age and Revolutionary War service had brought him some popularity. He was mentioned in a Bangor newspaper in 1851:

The first child born of the German settlers who founded Waldoboro’, is still living in that town (says Mr. Eaton, in the History of Warren.) His name is Conrad Heyer, born in 1749, now 102 years of age, and in the enjoyment of pretty good health.[13]

Also in 1851, local historian Cyrus Eaton published Annals of the Town of Warren in Knox County which included a paragraph about Heyer, saying he had “enlisted in the army in the fall of 1775, served upwards of two years.”[14] Eaton lauded him for having “ever been a hard-working, temperate man, and now, at the age of 102 years, is able to read fine print without glasses, though his hearing is somewhat impaired.” After the 1852 presidential election, newspapers around the country mentioned that “Conrad Heyer, of Waldoboro’, (Maine,) aged one hundred and three years the tenth of April last, notwithstanding a severe storm on the 2d instant, travelled six miles, and was at the polls as usual, and cast his vote for President.”[15] Some of the newspapers that picked up this snippet, however, added, “He served three years in the war of the Revolution.”[16] Somehow, after Heyer’s pension claim in 1819 and before 1851, word had spread that Heyer had served for longer than he’d originally claimed.

On May 21, 1855, Heyer himself revised his claim. In a statement reaffirming his pension claim, he stated that he’d been discharged in December 1778 rather than 1776. The printed form with specifics handwritten into blank spaces by a justice of the peace asserts that Heyer “was in the army when Burgoyne surrendered; for the details of his service refer to his application & proofs on which his Cert. of Pension was issued, dated July 14, 1819.” It further says that he “Enlisted first at Waldoboro State of Maine on or about the first day of December 1775 for the term of three years … was honorably discharged in the state of New York on or about the fifteenth day of December AD 1778 as will appear by the muster rolls of Capt. Smiths Company & other rolls. That he was at one time one of Genl Washington’s body guard.” At the time this document was prepared in Lincoln County, Maine, the “application & proofs” and muster rolls that it refers to were at the pension office in Washington, DC. Today, all of these documents are together in Heyer’s pension file, but in 1855 the justice of the peace took the one-hundred-and-six-year-old veteran’s statements at face value. No one since has seemed to question the inconsistencies.

It is possible that Heyer served in Washington’s life guard, a corps initially formed in March 1776 of men selected from each infantry regiment in Washington’s army. But there is no record that he did; complete muster rolls for the life guard do not exist, and his name is not among those known to have served in the corps. And once again there is no mention of Heyer crossing the Delaware, even in the inflated claim of service from 1855. Perhaps it arose from the assertion that he’d served in Washington’s guard, and therefore must have accompanied the commander-in-chief everywhere. A 1925 inquiry to the Pension Office shows that the Delaware claim was already popular at that time.

When he was photographed in 1852, there was no way to make copies of the daguerreotype picture. With the advent of the internet, however, images of the photograph have been widely circulated and acclaimed, along with the assertion that he was the only man who crossed the Delaware to be photographed, was the last survivor of that crossing, and so forth. Although a glance at his pension file seems to support the claims, a more detailed and discerning look indicates that they are simply not true. My work with the six aged veterans in The Revolution’s Last Men revealed how the military service of centenarians was exaggerated through a combination of fading memories and wishful admiration. The same appears to be true for Conrad Heyer: he certainly spent a year in the Continental Army, service worthy of study and commemoration, but the available evidence indicates that his soldiering days ended before Washington’s famous river crossing.

[1] The earliest occurrence I’ve found dates to January 8, 2008: https://unitedcats.wordpress.com/2008/01/08/the-worlds-first-eyewitness/

[2] See, for example, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/conrad-heyer-a-revolutionary-war-veteran-was-the-earliest-born-american-to-ever-be-photographed-180947660/

[3] For the most extensive collection of images of Revolutionary War veterans, see Maureen Taylor, The Last Muster: Images of the Revolutionary War Generation (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2010); The Last Muster Volume 2: Faces of the American Revolution (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2013).

[4] Don N. Hagist, The Revolution’s Last Men: The Soldiers Behind the Photographs (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2015).

[5] E. B. Hillard, The Last Men of the Revolution (Hartford, CT: N. A. & R. A. Moore, 1864).

[6] Conrad Heyer (Hyer) pension file, S35457, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1800–1900, Record Group 15; National Archives Building, Washington, DC, accessed through Fold3, Revolutionary War Rolls, http://www.fold3.com, accessed January 30, 2016.

[7] Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution (Washington, DC: Rare Book Ship Publishing, 1914), 56, 110.

[8] “A List of the Names & Rank of the Officers of the Twenty fifth Regiment,” William Bond Papers, Mss. 80, Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California San Diego.

[9] Ibid.; Heitman, Historical Register, 506.

[10] Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, 1983), 206.

[11] The most comprehensive source of information on Massachusetts militia service makes no mention of Conrad Heyer, or any likely name variations (Hyer, Higher, Hayer, etc.). Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1896).

[12] Bath Tribune, February 22, 1856; reprinted in a number of other newspapers.

[13] Bangor Whig & Courier, November 22, 1851.

[14] Cyrus Eaton, Annals of the Town of Warren in Knox County, Maine (Hallowell, Maine: Masters, Smith & Co., 1851). In 1877 a second edition of this book was published by Emily Eaton, who added, “some authorities say three years, and that he was in the army at Cambridge When the battle of Bunker Hill was fought; was a member of the advance guard at the crossing of the Delaware, and in many of the battles under Washington.” She also added this anecdote: “As Martin Heyer died from exposure and hunger after his arrival at Waldoboro’ before his son Conrad was born, the popular belief that a man ‘who never saw his father’ has the gift of healing sore eyes and other ills by a look or touch, led to Mr. Heyer being sought after for that purpose; and tradition tells of a wonderful cure thus performed for the daughter of a rich Bostonian in early days, but of whom, according to rule, no reward was accepted for fear of annulling the cure.”

Three months after Heyer died, it was announced that “The funeral obsequies of the old revolutionary soldier, Conrad Heyer, the oldest man known in this part of the United States, who died at Waldoboro’ some months ago, are to be celebrated at that place on the coming anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill – the 17th of June. The Rockland City Guards have accepted an invitation to be present.” Bangor Whig & Courier, May 27, 1856. The 1877 edition of Annals of the Town of Warren presented this as more than just a celebration: “This interesting man died Feb. 19, 1856… and the succeeding 17th of June was celebrated in Waldoboro’ by the disinterment of his remains and their re-burial with public military honors in the German burying-ground at the village where his fellow citizens have erected a monument to his memory.”

An 1869 news item about the Lutheran meeting house in Waldoborough noted that “Old Conrad Heyer acted as chorister in the old house for eighty years, and, although a hundred years old, would sing the highest notes with scarcely any of the tremulousness of age.” Boston Daily Advertiser, December 27, 1869, quoting the Rockland Free Press.

[15] Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), November 16, 1852. Earlier that year a Bangor newspaper included a paragraph about Heyer due to his being a centenarian. It reported that he had served three years during the Revolution, and that “He has nine children living, the baby being nearly three score years old. His wife died ten years ago, after having lived with her 65 years. He is of German origin being the first person born in Waldoboro, and knows no language but the German. His German Bible is his constant companion, which he reads daily.” This is the only indication that he spoke only German, and there is no evidence that he gave his pension deposition through a translator, suggesting that the statement is inaccurate. Rockland Gazette, February 27, 1852, quoting the Bangor Jeffersonian.

[16] See, for example, Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, November 23, 1851.

9 Comments

Thanks Don. Interesting as always.

Great article pointing out the importance of corroborating pensions with musters and other sources, and the danger of simply taking them at face value. Good stuff, sir.

Don, I really enjoyed this article and believe it is an extremely important one. For my research on the New Jersey militia I had to use pension files, local history sources, newspaper articles and obituaries about veterans since there were so few state records of individual militia service. The pension files were essential for helping me see the realities of militia service to complement the militia laws and other documents relating to the militia system.

Just a couple of reflections. Some of the exaggerations seem to reflect the importance attached to various events. They are instructive to how the event was interpreted in the early years of the republic. For example, a number of men claimed to have crossed with Washington and to have been at the battle of Trenton – when, in fact, they didn’t. To me this indicates they understood the significance of these events and wanted to be identified with them. In some cases, they were actually with Washington’s army at the time, but were with militia stationed at other crossing points that didn’t get across that night. Some of these men misremembered over time and were actually at the second battle of Trenton, before which they crossed the Delaware River, but mis-described it as the time the Hessians were taken. Exactly when battles, or any event, took place was often misremembered. I have seen examples of men who correctly state that they enlisted in a Continental regiment in 1777 or 1778, but then boldly state that they were at the Battle of Trenton.

Another incident many New Jersey men seem to have wanted to have been a part of was Washington’s confrontation with General Lee at the battle of Monmouth. Several New Jersey militiamen claim to have been close enough to see, and perhaps even hear, the exchange. Pension statements from other men in the same company state they were not near the main battle. This event must have been a topic of frequent conversation after the war.

Your article is so important because there are so many local history and family stories that are suspect or impossible to document. The pension files provide a very interesting source because the statements made by veterans were sworn court documents that only had to prove time in service – not quality of service. There was no need to tell heroic stories. In the case of the militia, since document records were so scarce, stories seem to have been often told to try to verify the service. However, they were made after a significant number of years had elapsed and conversations had taken place, events had been interpreted patriotically in various ways, etc. so that even attempts to remember correctly could go astray. Given the nature of the New Jersey militia system this could be a major problem.

All this is just to reinforce the importance of your fine article. Thank you for it.

Lots of good information in this article. I admire and appreciate your thorough research, too. Thanks! Nancy Loane

This article illustrates that many events of the Revolution were not recorded. Also many had language issues and many records are lost . Also many soldiers extended their original service in the war. I cannot say one way or the other about individual privates activities that may be losto history.

Excellent article and well researched. Doing extensive genealogical and historical research myself over the years, I have run into many similar inconsistencies that form into legend and perceived “fact” over time. In fact, some families of ancestors refuse to believe my research even when presented with undeniable facts from the written record….instead they cling to the family legends. Your research is detailed and thorough, thanks for sharing. BTW, I love the old Revolutionary War pension files…lots of fascinating information there! Well done!

Glad you enjoyed the article, Mike.

It is always puzzling when people cling to dearly-held beliefs even though there’s concrete evidence (or at least paper evidence) that proves otherwise. But, many people seem to do this even with current events, so it should be no surprise that some also do so with historical information.

Don thank you a great story about Conrad Heyer, really enjoyed it.

I just read Carlos Godfrey’s The Commander in Chief’s Guard , which doesn’t mention Heyer on the other hand the records of all the members were destroyed in a fire in 1815 at the Charlestown Navy Yard. So if he served 3 years did he transfer to the Guards and the records were destroyed?