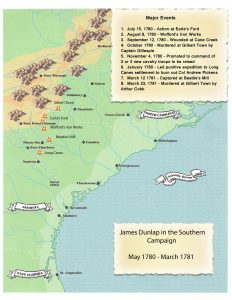

In January of 1781, Loyalist Maj. James Dunlap raided the Long Cane settlement in South Carolina that included the homes of notorious rebel leaders James McCall and Andrew Pickens. Among the most respected of all the Whig military men, Pickens had only renounced his parole the month before. Lord Cornwallis’s response was to send Dunlap (often spelled Dunlop) who he described as “an active, gallant officer.”[1]

In truth, Major Dunlap was far more than just an active and gallant officer. From the rebel point of view, he was a vicious and brutal man with a reputation for indiscriminate slaughter. Dunlap made his reputation in 1778 during a raid on Hancock’s House near Salem, New Jersey. In that action, he led his company around the rear of the house while the regimental commander, Maj. John Graves Simcoe, led the front assault. The two groups struck at the same time but Dunlap had “the more difficult way” by entering the back door. The night was dark and the two “companies had nearly attacked each other. The surprise was complete” and would have been even better except most of the rebel force had already left. As it was, Dunlap only found a “detachment of twenty to thirty men, all of whom were killed.”[2] In the commotion, Dunlap’s men also killed the civilians who happened to be loyalists.

The action at Hancock’s gave Captain Dunlap a solid reputation with the British for military competence. A year later, when Patrick Ferguson was recruiting for his newly formed regiment called the American Volunteers, Dunlap was chosen to come along, even though he remained a Queen’s Ranger. Ferguson would become the new Inspector of Militia for the southern colonies. Implementing the southern strategy involved recruiting and forming Loyalist militia regiments in all the districts. The south might offer opportunities for Dunlap to secure a separate command of his own.

Once in South Carolina with Cornwallis, Captain Dunlap continued to distinguish himself. At Earle’s Ford he led 14 dragoons and 60 militia into an assault against “a party from Georgia who had been plundering that day within a few miles of my post.” He charged into their camp “killing and wounding about 30 of the rebels and making them retreat some distance.” At that point Dunlap discovered that he had actually attacked a Patriot camp of near 400 men. He organized a hasty retreat back to Prince’s Fort. Unfortunately for the Captain, “the rebels, getting the better of their consternation and finding the smallness of my force, pursued me with a party of horse. The moment they appeared in my rear, the militia ran off to the woods and left me with only ten mounted infantry to make good my retreat.”[3]

In spite of having the militia desert him, Dunlap managed to make an organized retreat of several miles to Prince’s Fort. Once there, he found that several of the scared militia men had arrived first and spooked the garrison. Only a dozen men remained giving Dunlap a total force of about 22 regulars. “Expecting every moment to be attacked,” the captain decided to make a speedy retreat, which he accomplished “without molestation.” During the action, Dunlap only lost one of the regulars and two of the militia.[4] Even though forced to retreat with his militia scattered, Dunlap’s personal reputation for coolness and bravery remained intact.

In August Dunlap had a similar experience. Ferguson dispatched him with 14 regulars and 130 militia to take some rebel wagons near Cedar Springs. He chased one of the rebels right into their camp and found himself in an ambush. Before Dunlap could organize a retreat, he was wounded along with 20 or 30 of his men. The action was brief and inconclusive but, in Ferguson’s report to Cornwallis, Dunlap did very well. Due to the “backwardness of the rest of the militia, Captain Dunlap found himself under a necessity of attacking 300 men with 40, one half of whom are killed or wounded, and of the rebels as many, and half a dozen prisoners on each side.”[5] Ferguson also reported that the rebel leader, Elijah Clarke, had been mortally wounded but that claim was learned to be incorrect only a few days later at the Battle of Musgrove’s Mill.

In August Dunlap had a similar experience. Ferguson dispatched him with 14 regulars and 130 militia to take some rebel wagons near Cedar Springs. He chased one of the rebels right into their camp and found himself in an ambush. Before Dunlap could organize a retreat, he was wounded along with 20 or 30 of his men. The action was brief and inconclusive but, in Ferguson’s report to Cornwallis, Dunlap did very well. Due to the “backwardness of the rest of the militia, Captain Dunlap found himself under a necessity of attacking 300 men with 40, one half of whom are killed or wounded, and of the rebels as many, and half a dozen prisoners on each side.”[5] Ferguson also reported that the rebel leader, Elijah Clarke, had been mortally wounded but that claim was learned to be incorrect only a few days later at the Battle of Musgrove’s Mill.

By September Lord Cornwallis had carved out a command spot for Dunlap. A prominent Loyalist from North Carolina offered to “raise a corps and give command of it to Captain Dunlap of the Queen’s Rangers, who is serving with Ferguson. Dunlap is an active, spirited officer and, if he could get only 200 men, would be very useful in that country [Ninety Six District].”[6] Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour concurred with the assessment describing Dunlap as “active, knowing in the country and the manners of the country people, and very spirited. Whilst with me, he behaved rather well, rather too far forward in his patrols, by which he got into scrapes, but it is a fault which soon mends.”[7]

Balfour’s words about riding “too far forward in his patrols” proved instantly prophetic since, unknown to the lieutenant colonel, Dunlap had already been wounded riding ahead of Ferguson’s column near Cowan’s Ford in North Carolina. Ferguson reported that “Captain Dunlap was badly wounded by some skulking shots on the flank.”[8] Cornwallis found the news “particularly distressing as he was to have commanded a corps which old Mills of that County had engaged to raise for him.”[9]

Needing time to rest and recover from his wound, Captain Dunlap stayed in Gilbert Town, North Carolina while Ferguson continued on his efforts to trap Elijah Clarke’s refugees from Georgia before they could reach the safety of Watauga across the Blue Ridge. While in Gilbert Town, Dunlap got some information on the Overmountain Men and their efforts to raise an army against Ferguson. When all the regiments were added up, the rebel militia would be coming with a force of 2,000 men. Dunlap added, “do not make too light of all this, for advancing they certainly are, let their numbers be what they will.”[10] Ferguson responded correctly but did not act in haste. “2,000 I cannot face. I shall therefore probably incline eastward if I do not succeed in my present object in two days.”[11]

As every fan of the American Revolution knows, Ferguson remained at his camp atop King’s Mountain at least one day too long and the Overmountain Men provided him with crushing defeat yet glorious death. But what is not so well known is that, at the same time Ferguson met his end, Captain Dunlap faced his own demise at the hand of an “avenger.”

While researching for his epic book on the King’s Mountain campaign, Lyman Draper collected information from the Hampton family. They said that while Dunlap convalesced at Gilbert’s House, two or three men came by claiming to be Loyalists. Not suspecting any problem, Mrs. Gilbert let the men upstairs where they proceeded to question the wounded captain concerning the whereabouts of one Mary McRea. Apparently, Dunlap had kidnapped the young lady in hopes of convincing her to “encourage his amorous advances.” Unfortunately for Dunlap, Mary died while held captive. One of the men looking for her was her fiancé; when Dunlap confessed her death, the man “shot him through the body” before mounting up and riding off. The tradition held that “Major Dunlap” was buried just 300 yards away “south of the Gilbert House, the grave being still pointed out, marked by a granite rock at the head and foot.”[12]

But Captain Dunlap’s story didn’t end there.

In reviewing the Papers of Lord Cornwallis, it quickly becomes apparent that Dunlap did not die at Gilbert’s house. He recovered from his wound and returned to his duties by November of 1780. There is no mention of the incident at Gilbert House or of Dunlap having been shot a second time. Instead, Cornwallis returned to his plans for Dunlap to have a separate command. Now that Ferguson was gone, the British desperately needed a new cavalry troop for operations in the Ninety Six District. “Dunlap, who is an active, gallant officer, will have the rank of major and command the whole [2 or 3 cavalry troops to be immediately raised].”[13]

As might be expected, the British found recruiting for Provincial corps in the south substantially more difficult after Ferguson’s loss. To make the situation even more of a problem, they also lacked sufficient horses and equipment to mount a full cavalry troop. Major Dunlap stayed in Charleston securing the equipment and supplies until January of 1781. At that point Balfour reported that Dunlap had accoutrements for only one troop “and the rest will be sent as quickly as the swords can be got ready.”[14]

While Dunlap was in Charleston, the Ninety Six District broke out into rebellion. Col. Andrew Pickens renounced his parole and led the Long Cane regiment back into the field after six months of inactivity. Even though located in the back country, the Ninety Six District was actually the most heavily populated district of South Carolina and Pickens was its most dynamic officer. They were an experienced and well directed militia brigade of several regiments and having them break parole dealt a serious blow to the British southern strategy. Consequently, Dunlap’s first patrol as a newly promoted major was to be a visit to the Long Cane Settlement to deal out official retribution for Pickens’s treachery. In an angry letter, Cornwallis ordered Pickens’s slaves, cattle, and personal property taken and his “houses may be burnt, and his plantations, as far as lies in your power, totally destroyed, and himself, if ever taken, instantly hanged.”[15]

Major Dunlap carried out his orders with efficiency. “Captain Dunlap’s dragoons, united with parties of Loyalists, made a general sweep over the country. Colonel Pickens house was plundered of moveable property, and the remainder wantonly destroyed. McCall’s [Lt Colonel James McCall who now commanded a troop of South Carolina cavalry] family was left without a change of clothing or bedding, and a halter put round the neck of one of his sons, by order of Dunlop, with threats of execution, to extort secrets of which the youth was innocent.”[16]

At the time of Dunlap’s raid, Colonel Pickens and Lieutenant Colonel McCall were marching with Daniel Morgan and unable to respond. They remained with the Continental army through February before returning to South Carolina in early March of 1781. Now promoted to brigadier general, Pickens took command of all the partisans operating in the district. His first thoughts on returning were of Major Dunlap who was “detached from Ninety-Six into the country, on a foraging party; Pickens detached Clarke [Colonel Elijah Clarke who commanded the Georgia Refugees] and M’Call, with a suitable force, to attack him.”[17] Their orders were to leave the Loyalists alone except that “if they found any that needed killing not to spare them.”[18]

Clarke and McCall caught up with Dunlap at Beattie’s Mill on Little River. The rebels trapped Dunlap between them at which time he “retired into the mill and some out-houses, but which were too open for defense against riflemen; recollecting, however, his outrageous conduct to the families and friends of those by whom he was attacked, he resisted for several hours, until 34 of his men were killed and wounded; himself among the latter; when a flag was hung out and they surrendered. Dunlap died the ensuing night.” The Patriot historian Hugh McCall, who also happened to be the son of James McCall, then adds that “the British account of this affair, stated that Dunlap was murdered by the guard after he had surrendered; but such was not the fact, however much he deserved such treatment.”[19]

But Captain Dunlap’s story did not actually end there. Either Hugh McCall was ignorant of the full story or, as may be seen in other passages from his work, McCall shied away from recording the more inconvenient truths.

After his surrender at the mill, Major Dunlap and the other prisoners were sent “back to a little town in N. C. called Gilbert, where Dunlap was confined for some time, in an upper room, where one of our men (as was said) privately shot him dead with a pistol.”[20] In his report on the incident to General Greene, Pickens described the murderers as “a set of men chiefly known”[21] before naming one as an “Overmountain Man named Cobb.” Pickens said he put up a substantial reward for Cobb’s capture, an action which Greene praised as a “just and prudent measure to bring the criminals to justice.”[22] Pickens also sent word to the British commander at Ninety Six that all the American officers looked with “horror and detestation” on the murder. In truth, Pickens’s statements probably lacked sincerity since both sides knew the identities of the murderers yet none were ever arrested. The killers had been as unconcerned by witnesses as they had by the presence of Dunlap’s guards. The most detailed account of Dunlap’s murder comes from his fellow prisoner, Capt. Daniel Cozens of the New Jersey Volunteers. Vivid and gruesome:

Five of the rebel militia entered the room about eleven o clock at night and came over the bed with a lighted candle & immediately discharged two pistols at his head the explosion of which woke those officers that were sleeping with him & finding Captain Dunlap shot, they [implored] the Rebels not to murder them.” At that point the rebels noticed their shots had set the bed on fire which started to quickly burn out of control. In the confusion, the rebels began to threaten the other British officers with death if they failed to get the fire out, “which they did with the assistance of some water that lay in the room; they then demanded Captain Dunlap’s helmet, boots, & spurs and desired the officers with Captain Dunlap to lie down on which they left the room for about five minutes & then returned as before and one of them going up to the bed cried out, ‘Damn him he’s not yet dead’ and discharged another pistol at him, & then left the room. Some time after the officers with Captain Dunlap finding the Rebels had entirely left the house went to Captain Dunlap & found him still alive and able to Speak, desiring Captain Cozens to dress his wounds adding he thought he might live if good care was taken of him, the Officers dressed his wounds in the best manner they could, and sat up with him ‘till morning & then dressed him again by his own desire, but could afford him no further assistance being marched away immediately, but got leave for a corporal to take care of him, but the same party came into the room at two o’clock in the day with one Arthur Cob who did everything he could to distress Captain Dunlap by telling him he must be moved, etc. and on Captain Dunlap’s begging of them for God’s sake to let him die easy, Cob shot him through the body with a rifle as he was sitting up in bed supported by the Corporal, this the Corporal related on joining us the next day. A Major Evan Shelby lay in the same house all night, but did nothing to prevent the murder of Captain Dunlap; who the same night gave him eleven guineas to keep for him which he never returned. Sam & Elijah Moore, Captain Burnet of the Rebel Georgia Militia & one Damewood & Fox were perpetrators of this murder –[23]

At this point, it appears that Captain Dunlap’s story finally ended. There is little doubt that he was a courageous officer but opinions differ widely after that. From Cornwallis’s point of view, Dunlap was spirited, gallant, and just what was needed for cavalry operations in the Ninety Six District. From the Patriot perspective, he was closer to an eighteenth century terrorist. Regardless of which description comes closer to the truth, nobody can doubt that James Dunlap was a hard man to kill. He survived being wounded on the road to King’s Mountain. He survived being wounded at Beattie’s Mill. But at Gilbert Town, the Overmountain Men refused to be denied. They came to his room not just once or twice but three times, each visit for the purpose of pumping in a little bit more lead to insure Dunlap’s demise.

[1] Charles Cornwallis to Nesbit Balfour, November 4, 1780, in Ian Saberton, The Cornwallis Papers (East Sussex, Naval & Military Press, 2010), III:60.

[2] John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal (New York, Bartlett & Welford, 1844), 52.

[3] James Dunlap to Balfour, July 15, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, I:254.

[4] Dunlap to Balfour, July 15, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, I:254.

[5] Patrick Ferguson to Cornwallis, August 9, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:302.

[6] Cornwallis to Balfour, September 13, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:82.

[7] Balfour to Cornwallis, September 20, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:92.

[8] Ferguson to Cornwallis, September 14, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:148.

[9] Cornwallis to Balfour, September 22, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:88. In fact, there would never be a regiment raised by “Old Mills of Tryon Country” since he would soon be captured at King’s Mountain and hung in the subsequent Tory trials.

[10] Dunlap to Ferguson, September 30, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:160

[11] Ferguson to Cornwallis, September 30, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, II:161.

[12] Lyman Draper, King’s Mountain and its Heroes, (Cincinnati: P. G. Thompson, 1881), 160-161.

[13] Cornwallis to Balfour, November 4, 1780, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, III:60.

[14] Balfour to Cornwallis, January 7, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, III:131.

[15] Cornwallis to John Harris Cruger, January 13, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, III:292.

[16] Hugh McCall, The History of Georgia, (Savannah: Seymour & Williams, 1816), II:352.

[17] McCall, History of Georgia, 361.

[18] Pension Application of Thomas Leslie, File Number W381, http://www.revwarapps.org/w381.pdf.

[19] McCall, History of Georgia, 361.

[20] Pension Application of Joshua Barnett, File Number S32154, http://www.revwarapps.org/s32154.pdg.

[21] Andrew Pickens to Nathaniel Greene, April 8, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathaniel Greene, Vol. 8, Dennis M. Conrad, ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 71.

[22] Greene to Pickens, April 15, 1781, in Papers of General Nathaniel Greene, 98.

[23] Daniel Cozens, March 28, 1781, deposition for Sir Henry Clinton, reprinted at http://www.overmountainvictory.org/Gtown.htm.

Recent Articles

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

Recent Comments

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

It seems there is no way to know the details of the...