Recognizing the contributions and sacrifices of all combat veterans from any war is a meaningful American tradition. On June 2, 2015, the President of the United States awarded Medal of Honor to Army Sgt. William Shemin and Private Henry Johnson, both World War I soldiers. The President remarked, “We know who you are. We know what you did for us. We are forever grateful.”[1] The same thanks should be offered to the thousands of soldiers who served, died, were wounded or suffered the stress of intense combat during the American Revolution, but accurate personnel records and casualty numbers for various battles and engagements of the era remain elusive. Even more problematic is the challenge of identifying individual casualties by name. This article recognizes some of the soldiers who served in the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment at the Battle of Brandywine so that, to echo the President’s comments, for at least a few of these soldiers, we may know who they were and what they did.

The war’s dynamic operating environment made accurate record keeping difficult, many localized engagements went unrecorded, and surviving records lack continuity even for larger engagements involving Continental Line units.[2] Howard H. Peckham’s 1974 work remains the most comprehensive study of Revolutionary era American casualties and outlines the death, wounding, capture or disappearance of over 53,000 Americans.[3] Each of those individuals and many others who suffered both physical and psychological wounds associated with a savage civil war had a name and a story to tell. The surviving primary records and access to them facilitated by modern digitization and collaboration allow researchers with interest in specific units to study the activities of individual soldiers and generalize these actions as trends. One unit with relatively complete surviving muster and pay records is the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment during a fifteen month period, May 1777 to July 1778.[4] A study of this unit sheds new light on the unit strength, leadership, roles in key battles, and most importantly casualties suffered, specifically at the Battle of Brandywine, the unit’s first major engagement.

John B. B. Trussell’s 1977 study of the Pennsylvania Line attempts to quantify unit losses while acknowledging the tumultuous nature of the regiments that composed this part of the army. Trussell outlines the creation, expansion, contraction, reorganization and reduction of twenty-seven different regimental-sized units between 1775 and 1783.[5] He relied heavily on the Pennsylvania Archives for primary source material, and qualified his research “… not as conclusive information, but as representing the best information which it has been possible to assemble.”[6] The Pennsylvania Archives contain many point-in-time records or fragments rather than comprehensive muster or pay records which, for many units, simply did not survive the challenges of time. Most authors reference the Pennsylvania Archives when presenting casualty numbers and names. Analyzing individual pay and muster records for the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment provides greater detail and surprising results when compared to Trussell’s findings.[7]

Accounts of the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment’s performance in the battles of Brandywine and Germantown reflect a new and relatively inexperienced unit that demonstrated the generally uncommon discipline needed to stand and fight close-quarter combat action against more disciplined and experienced British units.[8] Trussell’s work fails to capture casualty figures that support the accounts of the intensity of combat the 9th endured as reported by those present on the Brandywine battlefield.[9] This discrepancy prompted a name-by-name analysis of the regiment’s soldiers given on muster and pay records to provide additional clarity on the actual number of casualties, and to measure the intensity of combat. To understand the experience of the 9th Pennsylvania at Brandywine it is first helpful to review the order of battle and provide an overview of events that placed the 9th Pennsylvania on the right flank of the American defensive line on September 11, 1777.

Order of Battle and Brandywine Summary

During the spring of 1777, Washington assembled elements of the newly formed, but seriously under-strength and untested, eighty-eight-battalion Continental Army in the Hudson River Valley for the 1777 campaign season.[10] Washington assigned the new 9th Pennsylvania Regiment to Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway’s 3rd Pennsylvania Brigade in Maj. Gen. Alexander’s (Lord Sterling) Division. Conway’s Brigade consisted of the 3rd, 6 th, 9th and 12th Pennsylvania regiments.[11] Conway, an Irish Catholic, had served in the French Army gaining combat experience against Frederick the Great prior to traveling to North America to serve with American forces in the Revolution.[12] Conway was not well liked by his officers possibly because he trained and regularly drilled the brigade, turning it into one of the best disciplined units in the Continental Army.[13] This discipline was tested on September 11, 1777. Conway and the 3rd Pennsylvania Brigade passed the test, and as a result of the unit’s performance at Brandywine, Washington selected the brigade as a lead unit in the American attack at Germantown on October 4, 1777.

During the attack at Germantown the brigade drove one of the best trained units in the British Army over a mile from their initial defensive positions.[14] Conway’s performance was a high point in his career in North America. Washington, unimpressed with Conway’s leadership in sustaining the initial success at Germantown and for his part in the Conway Cabal, was pleased to see Conway leave the Continental Army, under a cloud of suspicion, while at Valley Forge, but that was in the future.[15]

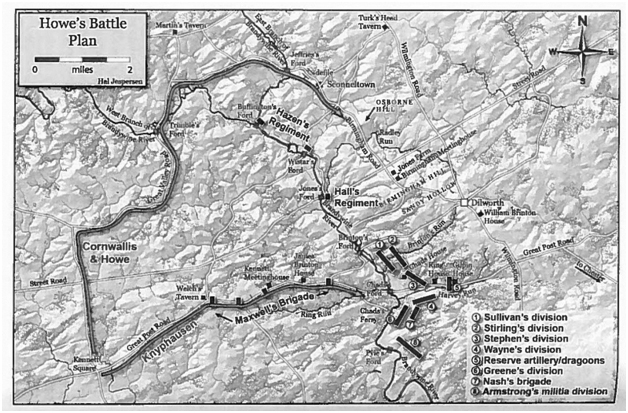

On the morning of September 11, 1777, the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment was part of a three-division force making up the right center of Washington’s Brandywine Creek defense in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Sullivan’s division, minus two regiments, occupied the ground east of Brandywine Creek between Chad’s and Brinton’s Fords. The two detached regiments guarded three additional fords, Jones’s, Wistar’s and Buffington’s, spreading elements of the division four miles to the north.[16] Sterling’s division faced west positioned behind Sullivan’s division and Stephen’s division was just to the south. The center of these three divisions was in the vicinity the Chads House not far from Washington’s headquarters in the Ring House. This disposition presented a defense in depth against an expected British attack moving from west to east across Brandywine Creek.[17] Washington assigned General Sullivan as the overall wing commander of this three-division force made up of six brigades containing about 4,000 soldiers.[18] Sterling’s and Stephen’s divisions were consolidated in one central location while portions of Sullivan’s division extended over four miles north along Brandywine Creek.[19] This disposition played an important role in the repositioning of the divisions to the north and contributed to the destruction of Sullivan’s division as a cohesive fighting force.[20] Map 1 provides a graphic representation of General Howe’s flanking march and the initial defensive positions of the American forces through approximately 2:00 p.m. September 11, 1777.[21]

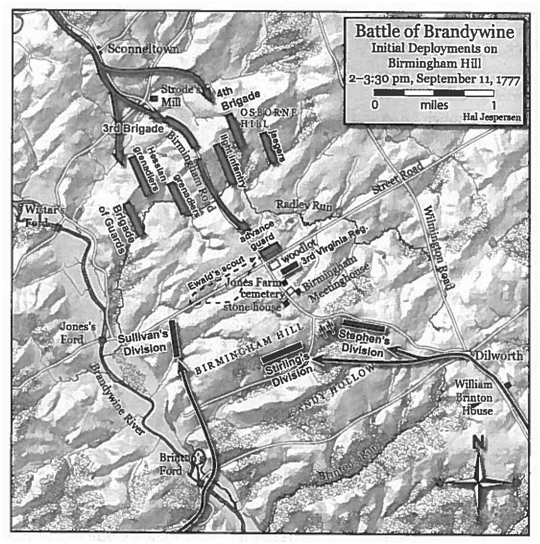

When Washington received credible intelligence at about 2 p.m. that he was about to be flanked from the north by the main effort of the British Army, he responded by ordering Sullivan’s, Sterling’s and Stephen’s divisions north to block the British advance. He held his remaining divisions and militia in place to blunt the supporting attack from British forces advancing from the west. Sterling and Stephen followed roads, first marching east then turning north and deploying along Birmingham Hill. Sterling and Stephen succeeded in deploying and positioning their divisions on reasonably defensible terrain along the crest of the ridge south of Birmingham Meeting House about one mile from the forming British lines. With a spirted sense of urgency, but moving cross-country with a lack of knowledge of both the terrain and enemy disposition, Sullivan took his division about one half mile forward of Sterling’s and Stephen’s divisions. The lack of adequate reconnaissance, poor roads and urgency in repositioning caused Sullivan to advance directly into the path of the attacking forces. This caught the division unprepared for enemy contact while in the act of redeploying. Most of the division disintegrated upon initial contact with the advancing British already deployed for the attack and prepared to assault Sterling’s and Stephen’s divisions. Portions of Sullivan’s broken division, including Hazen’s 2nd Canadian and Ogden’s 1st New Jersey regiments, successfully formed on Sterling’s left or open flank.[22] As a result of his division’s defeat, Sullivan found himself in command of only the two remaining divisions. Sullivan’s wing faced two-thirds of Howe’s Army; vastly outnumbered, the Americans engaged in a fight for survival.[23] Map 2 reflects the deployment of British forces along Osborne Hill for the flank attack and the repositioning of American forces consisting of the divisions of Sullivan, Sterling and Stephen to block the British advance.[24]

Sterling’s and Stephens’ divisions succeeded in forming a line of battle. Sullivan, separated from his division during the movement to contact, remained with Sterling and Stevens as the wing commander. Sterling’s division, including the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment, formed on the left with Stephen’s division on the right, facing the British to the north. The British column deployed about one mile north of Birmingham meeting House on Osborne Hill, in view of the American defenders. Sterling and Stephens had time to deploy skirmishers in front of their position to attempt to slow the British advance. The 3rd Virginia Regiment deployed and delayed the British from positions along Street Road, which ran perpendicular to the battle lines about half way between Osborne Hill and Birmingham Hill.[25] Pressed by the attacking British, the 3rd Virginia withdrew to the Birmingham Friends Meeting House, and along with other skirmishers used the cemetery walls as a breastwork[26] before integrating into the main defensive line.[27]

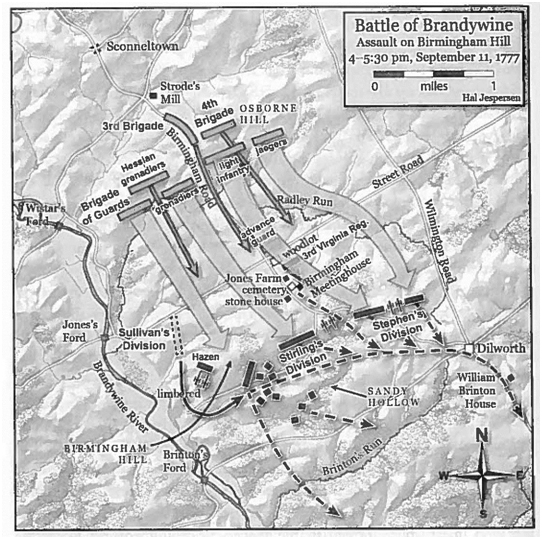

Unfortunately for the Americans, they were greatly outnumbered which exposed their flanks to attack. The British assault began about 4 p.m. As the fight for Birmingham Hill progressed, the Americans were outflanked on both the left and the right. They collapsed from the flanks to the center, the left collapsing first because of the failure of Sullivan’s division to cover that flank. As the flanks collapsed, the main line of defense along Birmingham Hill eventually gave way to a British bayonet assault.[28] Map 3 depicts the British attack on American forces deployed along Birmingham Hill and the American withdrawal.

Sterling and Steven selected excellent terrain on which to deploy their small divisions. This position is often referred to as Battle Hill, high ground covered with trees, an excellent defensive position. The entire fight lasted about one hour and forty minutes with the close fight for Battle Hill lasting fifty-one minutes “almost Muzzle to Muzzle.”[29] General Conway, a veteran of European wars and the 9th Pennsylvania’s brigade commander, indicated that he “never saw so close and severe a fire.”[30] As the American defense collapsed, General Washington arrived followed by General Greene’s reserve division which formed to the south of Battle Hill. Greene fought a delaying action until darkness ended the day’s action. Anthony Wayne’s division also fought a delaying action in the vicinity of Chad’s Ford. These two divisions remained cohesive and covered the American retreat to Chester. Exhausted from the day’s fight and the long flanking march, the British Army remained on the field and did not pursue the retreating Americans.[31]

Muster Roll Analysis

Payroll data for the month of August 1777 reflects a total 9th Pennsylvania Regimental strength of 332 officer and men.[32] This data is inconsistent with General Conway’s letter of August 15, 1777 to the Board of War, Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, indicating, “The four Pennsylvania Regiments in Brigade are Very Weak one is two hundred men strong, the three others are upon an average, one hundred and sixty.”[33] General Conway may have intentionally understated the strength of his regiments to dramatize the situation with the political leadership of Pennsylvania or the numbers of men available for duty may have been well below the number accounted for and paid. Data for December 1777 indicates seventy-two percent of the men on the payroll of the 9th Pennsylvania were actually present for duty; there is no comparable data for the August-September timeframe.[34] The seventy-two percent present and fit for duty is slightly higher than previously published research addressing the May to December 1777 time period for both Conway’s Brigade and the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment.[35] Assuming seventy-two percent of the men paid for August were present at Brandywine, the 9th Pennsylvania fielded 239 men assigned to eight different companies, as reflected in Table 1 below, with a regimental headquarters of eleven field and staff officers. Lt. Col. George Nagel served as commanding officer; Maj. Matthew Smith was his regimental major serving as second in command. The primary staff consisted of four men: William Thompson, adjutant; John Tate, paymaster; Thomas Craig, quartermaster; David Love, surgeon. Five additional staff assisted the primary field and staff including: Surgeons Mate Hamilton, Sgt. Maj. Robert White, Quartermaster Sgt. John Brandt, Drum Maj. John Brown, and Fife Maj. James Johnston.[36]

Table 1 lists the August 1777 payroll numbers for the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment for each of the eight companies and provides an estimated effective strength for the unit on September 11 at the Battle of Brandywine. The estimated effective strength is based on seventy-two percent of the men on the payroll present and effective for duty.

| Company | Officers | Sergeants | Corporals | Fifer &

Drummer |

Privates | Total

Payroll |

Estimated at

Brandywine |

| Bowen | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 42 | 30 |

| Davis | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 34 | 25 |

| Erwin | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 47 | 61 | 44 |

| Gourley | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 24 | 35 | 25 |

| Grant | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 20 | 14 |

| Henderson | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 44 | 57 | 41 |

| McClellan | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 32 | 43 | 31 |

| Nichols | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 29 | 40 | 29 |

| 31 | 22 | 19 | 12 | 248 | 332 | 239 |

Table 1: August 1777 Payroll Data & Estimated Effective Strength September 11, 1777 at Brandywine

Battle Casualty Analysis

Trussell’s research, sourced primarily from the Pennsylvania Archives, reflects one killed in action (KIA) and one wounded in action (WIA) at Brandywine.[37] Reviewing names and remarks from the company muster sheets and tracking individual names through the July 1778 muster records presents a total Brandywine casualty count of forty officers and men including eight KIA, sixteen WIA and sixteen missing in action (MIA).[38] Forty total casualties represent a 16.7 percent casualty rate for the regiment based on 239 effectives. The eight soldiers KIA served in five of the eight companies and include one officer and seven private soldiers. Table 2 presents their names and companies.

| Company | KIA Name |

| Bowen | None |

| Davis | None |

| Erwin | Pvt. Peter Johnson |

| Gourley | Ens. Benjamin Morris |

| Pvt. James McClellan | |

| Grant | Pvt. John Spence |

| Henderson | Pvt. Benjamin Morris |

| Pvt. Peter Miller | |

| McClellen | None |

| Nichols | Pvt. Samuel Hall |

| Pvt. Samuel Mullen |

Table 2: Brandywine Killed in Action by Company

A minimum of sixteen men received wounds on September 11, 1777. These men served in five of the eight companies as listed in Table 3. Wounded include one sergeant, one corporal and fourteen privates. Apparently a wound was not a death sentence as sometimes portrayed; eleven of the sixteen wounded men returned to duty, five of them within two months. Reportedly, only one died of his wounds, however four others eventually deserted.

| Company | WIA Name | Disposition | |||

| Bowen | None | ||||

| Davis | None | ||||

| Erwin | Sgt. Hugh Cull | No further record | |||

| Pvt. Joseph McMahon | Returned to duty Oct. 1777 | ||||

| Gourley | Pvt. Benjamin Coats | Hospital thru Feb. duty June 1778 | |||

| Pvt. William Moody | Hospital thru Feb. duty June 1778 | ||||

| Pvt. Hugh McIntosh | Hospital thru Feb. 1778, no further record | ||||

| Pvt. William Collins | Hospital thru Feb. duty June 1778 | ||||

| Pvt. Duncan Keenon | Hospital thru Feb. deserted 10 June 1778 | ||||

| Grant | None | ||||

| Henderson | Pvt. John Scott | Returned to duty Nov. 1777; deserted 14 June 1778 | |||

| Pvt. Joseph Brown | Hospital Oct. 1777, returned to duty Nov.; deserted 29 May 1778 | ||||

| Pvt. Francis King | Returned to duty Oct. 1777 | ||||

| Pvt. William Redman | Returned duty Nov. 1777 | ||||

| McClellen | Pvt. Jerry Connel | Hospital, died 20 Nov. 1777 | |||

| Pvt. Joseph Shaw | Hospital thru Feb. 1778; furlough May; returned to duty June 1778 | ||||

| Pvt. Adam Koch (Koagh) | Returned duty Oct. 1777 (Note 1) | ||||

| Nichols | Cpl. William Fegan | On furlough Feb. 1778; returned to duty June 1778 (Note 2) | |||

| Pvt. William Smith | Hospital Oct. 1778 to Feb. 1778; location unknown May 1778 (Note 3) | ||||

| Note 1: Pennsylvania Archives data indicates Pvt. Koch was wounded in the head, the ball entered below right eye exited below right ear; he resided in Bucks County 1806. Capt. Joseph McClellan’s notes for September 1777 reflect the following men in the hospital: Pvts. James Callaghan, George Schaffer, Jacob Prowles, Adam Koagh (Koch), John Connely, Peter Mager. Because Adam Koagh (Koch) was not listed as wounded, only in hospital, the others on the same muster may have been wounded on September 11. If that is the case, this adds five additional wounded to the totals. Pvt. Jacob Prowles hospital through February 1778, returned to duty May 1778 (National Archives 1775-1783). | |||||

|

|||||

Table 3: Brandywine Wounded in Action by Company and Disposition

Table 4 presents the sixteen men listed missing after the battle. The data on missing soldiers was much more difficult to extract from the muster and pay records and represents the best data available. Most men reported as missing have no further record in the regiment; their names simply disappear from the unit musters. Only one man eventually returned to full duty and one was listed as a prisoner of war (POW) in January 1778; as with the other men, his name disappears from the unit musters.[39] Five men deserted, four enlisting into Loyalist units.[40]

| Company | MIA Name | Disposition |

| HQ | John Brandt | Possible POW, taken with wagons (Note 1) |

| Bowen | None | |

| Davis | Pvt. Jacob Ringler | POW; enlisted in Maryland Loyalists Nov. 6, 1777, deserted Feb. 27, 1778; returned to 9th Pennsylvania March 7, 1778; deserted by May 1778 (Note 2) |

| Pvt. Edward Welsh | No further record | |

| Erwin | Pvt. John Kelly | Missing; enlisted in Maryland Loyalists Nov. 6, 1777 (Note 2) |

| Gourley | Pvt. Dennis McGrarty | Returned to duty |

| Drummer James McErvin | Absent; sick in hospital Dec 1777, no further record | |

| Grant | None | |

| Henderson | Pvt. Thomas Rolet | POW to Jan. 1778, No further record |

| Pvt. Robert Henry | No further record | |

| Pvt. William Hatton | No further record | |

| Pvt. Nathan Riley | No further record | |

| McClellen | Pvt. John Haughey | No further record |

| Pvt. John McDonnel | No further record | |

| Pvt. Daniel Hogan | No further record in regiment; enlisted Pennsylvania Loyalists Nov. 6, 1777 (Note 2) | |

| Nichols | Sgt. John Harst | No further record |

| Pvt. Andrew Walker | Missing, POW; deserted Oct. 1777 | |

| Pvt. Thomas Williams | Missing; no further record in regiment; enlisted in Royal Hunters Oct. 7, 1777 (Note 2) | |

| Pvt. John Sullivan | Missing; sick hospital Oct. 1777 to Feb. 1778; location unknown May & June 1778; possibly enlisted in Maryland Loyalists Nov 6, 1777 (Note 2) |

Note 1: Quartermaster Sergeant John Brandt was likely taken prisoner by the British along with the regimental wagons, although the record is not clear on this point. He is not included as one of the forty causalities for this reason.

Note 2: Loyalist enlistment records courtesy of research by Todd W. Braisted

Table 4: Brandywine Missing in Action by Company and Disposition

Analyzing the Data

The casualty data documenting forty men as KIA, WIA or MIA provides an insight into the intensity of combat experienced by the men of the 9th Pennsylvania at Brandywine. The forty casualties the unit experienced involved eight, or twenty percent, KIA, sixteen or forty percent WIA and sixteen or forty percent MIA. Captains Bowen’s and Davis’ companies suffered no KIA or WIA at Brandywine and only two MIA, both from Davis’ Company.[41] We can speculate that these companies served on detached duty and were absent from the line of battle. This could account for the lack of KIA or WIA as well as correlating with General Conway’s letter of August 15, 1777 complaining about the weakness of the Pennsylvania regiments, but in reducing the number of men available it would increase the casualty percentages of the portion of the regiment engaged. The two companies provided an estimated fifty-five men on September 11, as outlined in Table 1, and with those men missing from the line of battle, the actual casualty percentage of men engaged exceeds twenty percent. By modern standards this percentage of losses would render a unit combat ineffective.

Another fact that stands out is the number of wounded men who returned to duty, eleven of the sixteen men or sixty-nine percent. Five of these men returned within two months and all eleven by June of 1778, with only one recorded death; however, three of these men would eventually desert during May and June 1778. Another interesting finding involves the names of the missing men, ten of sixteen or sixty-three percent, simply being dropped from the unit rosters with no annotation of their disposition. Out of the sixteen missing men, three were POWs with one enlisting as a Loyalist, later deserting his Loyalist unit to return and desert the 9th Pennsylvania once more.[42] Three additional men listed as missing at Brandywine enlisted in Loyalist units. In other words, at least four of sixteen or twenty-five percent of the missing men deserted the revolutionary cause to enlist in Loyalist units within two months of the battle.[43] One is left to wonder if these men were captured and given a choice of enlisting as Loyalists or life in a prison cell as treasonists, or if they were opportunists seeking the best option for their personal survival in a brutal civil war. Only one of the sixteen missing men returned to full duty with the regiment.[44]

A name-by-name comparison of the company rosters over the fifteen month period between May 1777 and July 1778 proves interesting. Of the men on the company rosters in May 1777, only forty-seven percent remained in July 1778, that is, of the 239 enlisted soldiers serving the regiment in July 1778, only 112 had been in the unit fifteen months earlier. Captain Francis Nichols moved from company command to regimental major.[45] The eleven positions in the Regimental headquarters experienced a sixty-seven percent turnover with all new field grade leadership including a new commanding officer and a new regimental major.[46] These findings validate the often referenced instability and lack of continuity experienced in the Continental Army caused by extensive personnel turbulence and regular turnover of officers and enlisted men. The 9th Pennsylvania provides a model upon which to gage the degree of turbulence experienced by most regimental-sized units in the Continental Line.

Although the regimental headquarters experienced significant personnel turnover, the regimental senior leadership did not abandon the revolutionary cause nor did they leave their leadership positions because they were ineffective. The commanding officer, Lt. Col. George Nagel, received a promotion to colonel and served as commanding officer of the 10th Pennsylvania Regiment from February 7, 1778 to July 1, 1778.[47] Nagel then retired from active service when reorganization and consolidation of the Pennsylvania Line eliminated his position because of seniority.[48] Maj. Matthew Smith also received a promotion to lieutenant colonel but resigned his commission during February 1778 to serve on the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, representing Lancaster County. [49]

Conclusion

Brandywine was the first significant combat experienced by the 9th Pennsylvania Regiment. By all accounts the regiment performed well under the stress of combat, suffering significant casualties in standing their ground against a numerically larger and better trained and experienced enemy. Systematically researching and recording the names of the men of the 9th Pennsylvania who served, died, were wounded or went missing at Brandywine helps place the human face on the cost of combat and clarify the actual number of combat losses suffered and turbulence experienced by one regiment. It also brings to light some of the names of the tens of thousands of Americans impacted by the American Revolution including the one percent of the population of the United States that perished in gaining American independence from Great Britain.[50] The Continental Congress, the states, General Washington and unit leaders persisted and prevailed when similar losses and personnel turbulence would render units combat ineffective in today’s environment. To name the fallen and those intimately involved is not only an act of gratitude but a reminder of the grit and determination necessary for a citizenry to sustain a democracy.

[1] Barak Obama, Remarks by the President at Presentation of the Medal of Honor, The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, accessed 20 June 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/06/02/remarks-president-presentation-medal-honor

[2] Charles H. Lesser, The Sinews of Independence: Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), xi-xxix.

[3] Howard Henry Peckman, The Toll of Independence: Engagements & Battle Casualties of the American Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 130.

[4] War Department, 9th Pennsylvania Regiment, 1777-1778, Folders 36-1 to 36-6; Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M246, roll 83); War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93; National Archives, Washington, DC.

[5] John B. B. Trussel, Jr., The Pennsylvania Line: Regimental Organization and Operations, 1775-1783 (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1977), 246.

[6] Ibid., 264.

[7] Ibid., 327-351.

[8] John Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, Continental Army, ed. Otis G. Hammond (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1930), 1:458, 474, 563.

[9] Ibid., 1:458, 465.

[10] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, roll 83; Lesser, The Sinews of Independence, 46, 50; Robert K. Wright, Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, DC: Center for Military History,1983), 91-119.

[11] Thomas Lynch Montgomery, ed. Pennsylvania Archives, Series 5, Volume 3 (Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Publishing Company, State Printer, 1906), 522-523; Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2006), 1:370.

[12] Preston Russell, “The Conway Cabal,” American Heritage 46 (1) (1995): 1, accessed 7 May 2015, http://www.americanheritage.com/content/conway-cabal.

[13] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 577.

[14] Ibid., 542,-547, 576.

[15] Russell, “The Conway Cabal,” 1.

[16] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 549.

[17] Michael C. Harris, Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savis Beatie, 2014), 218.

[18] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 451; Lesser, The Sinews of Independence, 50; McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, 1:169.

[19] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 459; McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, 1:169-173.

[20] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 462-466, 549.

[21] Harris, Brandywine, 218.

[22] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 462-464; Harris, Brandywine, 271-272.

[23] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 466; John F. Reed, Campaign to Valley Forge: July 1, 1777 to December 19, 1777 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965), 117-140; Harris, Brandywine, 273.

[24] Harris, Brandywine, 278.

[25] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 465; Harris, Brandywine, 272, 278.

[26] Nancy V. Webster, 1777 Battle of Brandywine Driving Tour (Brandywine Battlefield Park Associates, 1986), 2.

[27] Harris, Brandywine, 299-301.

[28] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 465; Reed, Campaign to Valley Forge, 134; Harris, Brandywine, 299-322.

[29] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 465.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, 465; Reed, Campaign to Valley Forge, 139-140; McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, 1:260, 269; Harris, Brandywine, 323-369.

[32] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, roll 83.

[33] Samuel Hazard, ed., Pennsylvania Archives; Series 1, Volume 3 (Philadelphia, PA: Joseph Severns and Company, 1853), 522-523.

[34] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, roll 83.

[35] Lesser, The Sinews of Independence, 46, 50, 53, 54.

[36] Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, Series 5, Volume 3, 393-394.

[37] Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 277.

[38] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, roll 83.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid; Todd W. Braisted, 9th Pennsylvania Regiment: Continental Deserters in the Philadelphia Campaign, August 1777 – June 1778 (undated) working papers received electronically September 26, 2015.

[41] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, roll 83.

[42] Braisted, 9th Pennsylvania Regiment: Continental Deserters; Jacob Ringler enlisted November 6, 1777 in the Maryland Loyalists. He was enlisted by Captain Patrick Kennedy and deserted February 27, 1778. Library and Archives Canada, RG 8, “C” Series, Volume 1904, 15, 27; “Jacob Ringler, a German, five feet nine inches high, eighteen years of age, fair complexion, wears his hair tied; it is probably he may pass for a British deserter, as he lately left them; had on and took with him a British coat, white cloth coloured jacket and breeches, yarn hose, good shoes, and a silver faced watch; he has been seen betwixt Potts Town and Reading some time past.” Pennsylvania Gazette, August 18, 1778.

[43] Braisted, 9th Pennsylvania Regiment: Continental Deserters; Daniel Hogan enlisted November 7, 1777 in the Pennsylvania Loyalists, enlisted by Captain Francis Kearney, listed as a prisoner of the Spanish in muster of April 24, 1780 and exchanged at the Island of Jamaica in the muster of April 25,1782. Library and Archives Canada, RG 8, “C” Series, Volume 1906, ; Volume 1907, 1, 49.

[44] Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, roll 83.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, Series 5, Volume 3, 393-394; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution. Washington, D.C., 1892) 46, 306, 309, 372. Heitman’s data on officers is valuable as a starting point, but contains many errors, specifically with the officer of the 9th Pennsylvania, and must be verified against the muster data and other sources.

[47] Heitman, Historical Register, 409.

[48] Trussell, Pennsylvania Line, 120.

[49] Heitman, Historical Register, 505-6; State of Pennsylvania, Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of the State of Pennsylvania, Vol. 11 (Harrisburg, PA: Theo. Fenn & Co. 1852) 502, 618.

[50] Peckham, The Toll of Independence, 130; Wright, The Continental Army, 93; Peter Smith, American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790 (Glouchester, MA: Columbia University Press, 1966), 6-8.

5 Comments

Having conducted similar research into the unit I represent as a reenactor, I found your article quite interesting. I am curious to know if you have investigated the pension records for many of the men in the 9th Pennsylvania? I found a considerable amount of information on my unit including the names of additional men who served in the unit for a campaign season. From my perspective, the most important information came in the form of anecdotes of individual experiences. I suspect you would find a great deal of satisfaction in reading those accounts as well.

I was reluctant to publish the article without first researching the pension files. I have done some research on other topics at the National Archives on Pennsylvania Avenue and at College Park, but that was several years ago. Based on my schedule, I have been unable to devote the time needed to visit the Archives. However, that step will come in the future when the time becomes available for that important addition to the research. As you are aware, research never ends. Thank you for confirming my thoughts on the value of a visit to the textual records section of the National Archives to research the pension files of the men of the 9th PA.

Thank you for your very informative article. My 8th generation grandfather was assigned to the 9th Pennsylvania in Henderson’s Company. He fought at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and “at the battle and taking of Lord Cornwallis.” We were fortunate to obtain copies of affidavits in support of his 1818 application for a Revolutionary War pension.

It is because of him that I am a member of the Sons of the American Revolution, and proud of his service to our country!

Thank you for your service to our country and for your research into the 9th Pennsylvania. Your paper corroborates the 9th PA Regiment muster that lists Peter Miller and Benjamin Morris as KIA on September 11, 1777.

Can you point me in the direction of other sources pertaining to the 9th Pennsylvania, and particularly the contribution of those from Westmoreland County?

Loved this article. It was very informative. There seems to be some confusion about where the wounded afore mentioned Adam Koch’s grave (McClellen) is located; one is Pennsylvania and the other North Carolina. The problem I think stems from the fact that there were several people involved in the Revolution named Adam Koch. Hopefully one of these days this will be cleared up and corrected so that the right Adam Koch will be honored for his contribution to the Revolution. Whichever one he may be.