At the same time that George Washington and the Continental army besieged Thomas Gage and his forces at Boston in November 1775, Britain’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the south, John Stuart, sent a letter to Gage. Within, Stuart warned Gage that his situation had grown considerably precarious in the south, as “the competition for the friendship of the Indian Nations in this district will be great.” Yet if anyone was able to handle the complexities and nuances of England’s alliances with Native Americans, it was Stuart, a former trader among the Cherokee who also cultivated personal ties with the Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw – the four major indigenous powers in the south. Why, then, did Stuart try and temper the expectations of his superiors, and as early as 1775? As Stuart’s correspondence during the war reveals, he time and again took up the pen to complain that “the competition between me and the Rebel Agents for the Friendship of the Indians has been very great.”

Who, or what, had Stuart so anxious about his chances to enlist indigenous leaders? As Stuart divulged, it was “The Person Employed by the disaffected of Carolina and Georgia to Counteract me…one George Galphin who has for many years past carried on an extensive trade to” the Native peoples in the south. Stuart feared Galphin’s “weight and consequence, [which] has been greatly increased by his having been for several years past employed” by the empire “to conduct whatever business [it] had to transact in [the] nation[s].” In short, the revolutionaries had a Stuart of their own, and dare say, a man of greater means and connections in the Native south than Stuart himself.[1]

It should come as no surprise, then, that Stuart attempted – rather unsuccessfully – to convince indigenous leaders not to listen to Galphin, for “Mr. Galphin is a Trader but he is not a Beloved Man; he tells you that he will supply you … But I will tell you the Truth; he cannot.” According to Stuart, only when “the Rebels are reduced to Obedience and Reason” would Native peoples again “have plenty amongst you and be happy.” When words failed, though, as they often did for Stuart in the first years of the war, he plotted with the Governor of East Florida, Patrick Tonyn, to get rid of their Galphin problem. Tonyn cryptically instructed a group of Florida Loyalists under the command of Samuel Moore in early 1777[2] to proceed to Georgia and “do the Business without any of the Kings Warriors.” What exactly was Moore’s business? “to Kill [George] Galphin.[3]

Upon receiving intelligence that a “gang of the Florida Scout … are after Mr. Galphin,” Gen. Lachlan McIntosh of the Continental army scrambled to “collect all [our] Regiment that can be got together … to intercept [that] party.” However, McIntosh failed to reach Galphin in time, and Moore’s “Party … way-laid the Road on the day when Mr. Galphin was to have set out with [their] Indian [allies]” from his Silver Bluff plantation. But, as luck would have it, Galphin “received Information of it” ahead of time, undoubtedly from his Creek supporters Nea Mico and Neaclucko of Cusseta. Galphin therefor remained behind while a unit of the Georgia militia, led by Capt. John Gerard, took Galphin’s place in escorting their indigenous allies back to Creek country. Despite the armed escort, though, Moore and his men, mistaking Gerard for Galphin – “they being much alike” – still ambushed the militia and during the melee, shot Gerard dead. Although the militia, and the Creeks under their protection, returned fire and gave chase “till they [the Loyalists] took to a Swamp,” Moore and his men ultimately escaped, all the while believing they had killed Galphin. As Stuart shortly thereafter gloated in his letters to London, “We have a flying report that Mr. Galphin is Dead!” But even when Stuart learned the truth that Galphin still lived, he tried to arrange Galphin’s assassination again, sending the same man to finish the job. Only this time, Galphin was waiting. In the dead heat of July 1778, a motley crew of Georgia militia and Creek Indians – sent by Galphin – “discovered … Moore” and during their brief exchange of gunfire, “Moore … was killed, and 9 of his gang taken prisoner.”[4]

So what can this strange series of events, and more so Stuart’s fears and anxieties about his rival, tell us about George Galphin and the American Revolution? For starters, Galphin was not only an important figure, but an essential component of the American war effort in the south. However, historians of the Revolutionary War have altogether neglected, or outright dismissed, this man and his efforts to counteract British efforts to draw the Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw nations into the conflict.[5] One could legitimately argue that Galphin was the one man who stood in the way of the revolutionaries losing the south between 1775 and 1778, before the British switched their focus from the northern colonies to the south as part of their “Southern Strategy.” In fact, Galphin proved so important in undermining British influence in the Native south that British leaders determined the only way to gain the upper hand was to kill Galphin and remove him from the equation altogether.

Now who was George Galphin? As colonial newspapers attest, he was “a Native of Ireland – and a Gentleman, distinguished by the peculiar Excellency of his Character – of unbounded Humanity and Generosity – incapable of the least Degree of Baseness – and so much esteemed throughout the whole Creek Nation” and other indigenous societies in the south. Yet Galphin hailed from humble beginnings as the eldest son of a poor linen-weaving family in County Armagh, Ireland. In 1737, he left Ireland for South Carolina where he entered the deerskin trade as a lowly Indian trader for the firm Archibald McGillivray & Co. But over the course of three decades, Galphin reinvented himself as a reputable trader and merchant, and established a reputation as one of the most trustworthy and dependable intermediaries for Native and European peoples in the south, which only added to the weight of his growing political and commercial importance. As the naturalist William Bartram observed, Galphin “possessed the most extensive trade, connexions, and influence, amongst the South and South-West Indian tribes.” In particular, Galphin owed much of his importance to his Creek wife Metawney of Coweta, who ushered Galphin into the Creek world and facilitated his relationships with her clansmen like Escotchaby and Sempoyaffee, two of the primary headmen of the Lower Creeks during the mid to late eighteenth-century.[6] These men in turn propelled Galphin into the major political and commercial circles of the Native south, elevating Galphin to a position as one of the premier cultural brokers between indigenous and European worlds, especially for the Creeks and the British empire. Such connections throughout the Native south also attracted a wealth of imperial and colonial authorities, as well as transatlantic merchants, who flocked to Galphin in search of political and commercial relationships with him. For when it came to Indian affairs or the deerskin trade in the south, nothing happened without Galphin knowing about it or having a hand in it. Galphin was, for all intents and purposes, a one-man force of nature, often called upon by colonial and imperial administrators, like James Habersham, to serve at the empire’s behest. As Habersham confided to Galphin, “you have it more in your power than any person I know to induce the Creeks” or other indigenous peoples to a particular purpose.[7]

Of course, then, the revolutionaries wanted someone with Galphin’s prestige and connections that rivaled, if not eclipsed, Stuart’s own. It is no coincidence that Continental Army generals, such as Benjamin Lincoln, and Continental Congress delegates, like Henry Laurens, approached Galphin as early as October 1775, as “We think it of great moment that you Should have a personal interview with [the] Indians” on their behalf. As many of these revolutionaries understood, the Native peoples of the south – and particularly the Creek nation – held Galphin in high regard. According to indigenous leaders like the Tallassee King, Galphin “was looked upon as an Indian.” Also, contrary to Stuart’s claims, many headmen perceived “Mr. Galphin [as a] Beloved Man,” and as one who “had the Mouth of Charleston,” a title by which Native leaders recognized – and even designated – Galphin as their proxy to the Carolina and Georgia colonies. Further, the revolutionary leadership knew that Stuart hated Galphin with a passion, having written to his acquaintances in London that “I never suffered myself to be duped by him, for neither his knowledge nor intelligence were never necessary for me.” In Stuart’s mind, Galphin was a rival to his own power as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, as Galphin was not “in any respect responsible to the Superintendent, [who] may with impunity oppose his measures and … render them abortive.” In short, Galphin was a massive thorn in Stuart’s side, and the revolution’s leaders sought to exploit such a rivalry.[8]

However, Galphin was at best a reluctant revolutionary. Even though he promised the American rebels to do all “in my power … to keep the [Indians] peaceable,” he admitted that “I am sorry an Independence is declared for I was still in hopes affairs would have been settled, but now it is all over.” In fact, he dreaded “they were [all] in Hell … now as there is an Independence declared” as there would be “so many brave men killed & God knows when there will be an end to it.”

Galphin’s initial reticence to support the revolutionary movement stemmed from his fears of what the war might do to his family. To Galphin, family meant everything; he surrounded himself with, employed, protected, and bequeathed all his wealth to his kinsmen. The Galphin clan in North America included his Creek, Irish-French, and African children; his Scots-Irish sisters, nephews, nieces, aunts, and uncles; his Anglo and Scots-Irish cousins, nephews, and nieces; as well as his Creek, French, and Irish wives and mistresses.[9] Needless to say, Galphin was a family man, and dutifully feared for the futures of his children and kinsmen. But when push came to shove, Galphin embraced the rebellion, as rumors spread that Stuart intended to incite the Native south against the revolutionaries. Fearing for the safety of his family, Galphin felt “‘twas a Duty Incumbent on me … knowing my interest in the Creeks was so great, that it was not in the power of any Man [i.e. Stuart] to set them upon us if I opposed them.” By siding with the rebels, Galphin gambled everything on a revolution he did not necessarily believe in, motivated by his concern for family and their futures now threatened by the empire. As Galphin reveals to us, then, one’s loyalties during the war were just as much defined by one’s personal circumstances as they were by imperial or republican ideologies and identities.[10]

To deal with the imminent threat that Stuart posed to the colonies, the South Carolina and Georgia Councils of Safety – later followed by the Continental Congress – quickly appointed Galphin their “Indian commissioner.” But in assuming such a role, Galphin demanded the American “Indian Department” operate out of his home at Silver Bluff, staffed by the family and friends he surrounded himself with. Galphin thereafter transformed his plantation into a base of revolutionary resistance. In particular, he mobilized his connections in the Native south to create one of the largest information-gathering infrastructures in that region. As Stuart lamented, “it is impossible to prevent the Rebels having Emissaries and every sort of Intelligence … as every Trader has his Packhorsemen, and hirelings, and there is one perhaps two, three Traders in every Town of the [Indian] Nations with their hirelings.” He concluded, “there cannot be then by any wonder that Mr. Galphin finds Spies and Tools amongst them.” To make matters even worse for Stuart, Galphin maintained old – and cultivated new – alliances with many of the indigenous leaders in the south, a number of whom refused to go to war for either side, which was more than enough for Galphin. Furthermore, leaders like Captain Aleck of Cusseta, the Tallassee King and his “Son,” the Handsome Fellow of Okfuskee, and Wills Friend, acted as Galphin’s “Informer[s]” and relayed information to his “Spies and Tools.” Galphin then redirected such information to the Councils of Safety, Gen. Benjamin Lincoln in Charleston, and to the Provincial and Continental Congresses.[11]

Galphin also converted Silver Bluff into a base of operations for the Continental army, allocating plantation resources and manpower to support the war effort. In 1776 and again in 1778, Galphin conspired with Gen. Charles Lee to lead an “irruption into … East Florida” with Lee at the head of an army, while Galphin would calm “the minds of the Creeks,” a plan which Lee considered “of the highest consideration.” In preparation for the expeditions, Galphin modified his “trading boats” to be troop carriers “fitted up in the manner of Spanish Launches with a piece of cannon in the prod,” with intent “to go for [St.] Augustine” to seize that British fortification. Spanish observers in Havana marveled at “Maestre Galfen” who readied weapons, provisions, and soldiers for transport to East Florida. Despite Galphin’s logistical maneuverings, the expeditions never materialized because plans for the invasion were discovered by British spies. Yet the Continental Army also used Silver Bluff as a supply depot and a staging ground against Loyalist guerillas, leading to the construction of a “train of Artillery,” an army hospital, and a permanent garrison on the plantation. As word of his “unwearied exertions” spread, most of those in support of the revolution knew Galphin’s name, including George Washington.[12]

Of even greater importance, Silver Bluff emerged as the center for negotiations with the Native peoples of the south. For instance, in fall 1776, Galphin opened his doors to Creek leaders from the towns of Cusseta, Yuchi, Okfuskee, Tallassee, Hitcheta, Coolamies, and others, where he cautioned them not to listen to “the Kings people” and to remain “steadfast friends,” offering a wealth of “goods for you here.” In speaking to those Native headmen, Galphin reaffirmed his fictive familial ties to them, counseling “My Friend[s], I hope you nor none of your people will concern” yourself with the war. Native leaders responded in kind, that they “look upon Messr. Galphin … not only as Elder Brother but as Father and Mother,” and that “Whatever Talks Galphin … shall send … [we] will stand to [it].” And in keeping with the familial theme, Galphin framed the Revolutionary War in terms that he and his indigenous allies understood best, that it was a “Family Affair between England & this Country,” or a “dispute between a Father & his Children.”[13]

While Galphin advocated for – and largely secured – the neutrality of the Creek and other Native populations in the south during 1776 and early 1777, the assassination attempt on his life dramatically changed things. In Galphin’s mind, Stuart and his “Cowardly Dogs” had crossed a line and there was no turning back, particularly after Stuart put out a “£500 Reward for me Dead or live.” From here on out, Galphin labored zealously to banish British agents from their stronghold in Creek Country, setting in motion what became known as the “British Expulsions of 1777.”[14] Rallying his Native allies in fall 1777, Galphin managed to evict all of Stuart’s traders and spies in the nation. As headmen from the town of Cusseta recalled that event, their warriors forced the British to “run off in the Night to Pensacola, after they were gone the Cusseta Women went over to their houses and pulled them down.” Some of those British agents, like William McIntosh, barely escaped with their lives, after “a fellow called Long Crop from the Cussetas with some others yesterday came over here with a View to take my Scalp, [but] he mist his aim.” Shortly after, Galphin reveled in the fact that he and his allies “got all Stuarts Commissioners Drove out of the nation [and] the [Creek] plundered … upwards of 100 horse Loads of ammunition and other goods that was Carried up there to give the Indians to Come to war against us.” It seemed, then, by the end of 1777, Galphin had seized the upper hand, while further heartened by news from the north that a British army surrendered at Saratoga.[15]

However, the war took a darker turn for Galphin and the south in 1778 when the empire implemented its “Southern Strategy.” Largely a response to France and Spain’s entrance into the war that transformed that conflict into a global war, Britain turned its attentions toward the south in hopes of enlisting the large number of African slaves, Loyalists, and Native peoples to fight against the revolutionaries, thereby freeing the British army to protect other parts of the empire, particularly the West Indies. After a string of British victories at Savannah and Augusta in December 1778 and January 1779, Galphin found himself cut off from his American allies and forced to fend for himself. Shortly thereafter, a band of Loyalists raided Galphin’s stores, depriving him of a great quantity of trade goods he used to ensure the neutrality or support of indigenous leaders. Moreover, Galphin recognized that not only he, but also his entire family was in danger. Therefore, when the British threatened to come “upon us Like a Clape of thunder,” Galphin wrote to his allies that “georgia is taken by the kings troops & all Continental troops is taken out of it.” After which, Galphin guided his family away from Silver Bluff, “travel[ing] all night” until they reached a safe haven, where Galphin then “left them … & Returned back” to face the impending arrival of the British army. As Galphin intimated to his family and friends, “I Shall Stand as Long as I Can.”[16]

Yet the British were not Galphin’s only problem. Cut off from the lifeline of trade that sustained his efforts to keep the Native south peaceable or at least neutral, Galphin was at the mercy of what little supplies the Georgia revolutionaries had on hand. It wasn’t nearly enough. After 1778, Galphin endured a chronic shortage of goods that he could send to his indigenous allies, whereas Stuart enjoyed the full commercial might of the empire. To compound matters, those in the South Carolina Provincial Congress challenged Galphin’s loyalty to the revolution. As Henry Laurens informed Galphin, there was “an attack upon your Character” by one Dr. David Gould and “Reverend [William] Tennant who had twice before intimated doubts of your attachment” to the cause. In particular, Gould and Tennant alleged that Galphin – unable to risk giving away supplies from his already depleted stores – angrily swore at them and stated, “Damn the Country [for] I have lost enough by it already.” Such rumors about Galphin’s hesitant loyalty persisted throughout the war. However, the greatest blow to Galphin came from his own family when two of his nephews – and intended successors – David Holmes and Timothy Barnard defected. Together, Holmes and Barnard redirected a significant portion of Galphin’s resources to Stuart and the British, largely in hopes of monopolizing “the Trade … to West Florida” then under British control. To Galphin’s horror, his nephews also joined Stuart as “Commissioner[s] for exercising the Office of Superintendent of Indian Affairs.” This betrayal stung Galphin so badly that he filed a codicil to his last will and testament by which he disinherited Holmes and Barnard.[17]

To make matters even worse, the frontier inhabitants of Georgia – even those who sided with the revolutionaries – undermined Galphin’s efforts to maintain peace between indigenous and Euro-American peoples. As Galphin confided, “most of [those] people … has wanted an Indian War Ever Since the Difference between America & England, & [do] everything in their power to bring it on.” In one particular instance, backcountry residents invaded one of Galphin’s councils with Native leaders, where they threatened “three or four Indians” and declared to Galphin “they will kill them wherever they meet him.” On another occasion, Galphin alone faced the wrath of these people, “Some of [whom] Said I had got the better of them now in keeping the Indians peaceable, but it would not be Long before they would Drive me and the Indians both to the Devil.” Or more explicitly, they “would Come & kill me & the Indians.” Galphin now found himself threatened on all sides; with the British Army nearly upon him, without the supplies necessary to give indigenous allies and neutrals, betrayed by members of his own family, and even suspected and threatened by those on the side of revolution.[18]

In early 1779, British forces under the command of Archibald Campbell occupied Silver Bluff, renaming that place Fort Dreadnought while putting Galphin under house arrest until he could be put on trial for “high treason.” But even though a prisoner of war, Galphin continued to undercut British Indian affairs in any way he could. For instance, he managed to sneak a year-long correspondence between himself and his revolutionary allies, at one point optimistically stating “we should still be able to drive the Enemy off or pen them up.” In addition, Galphin continued an under-the-radar diplomacy with Native leaders, such as the Tallassee King, who ventured to Silver Bluff under the pretense of seeing their “friend.” At one of these clandestine meetings, Galphin boasted that “We’ve been at war with the English for four years, and they couldn’t beat us, what can they do now that the French and Spanish are on our side?” In return, the Tallassee King presented Galphin with a “white wing and Beads” to signify their continued support of the revolution. And when American propagandists learned of Galphin’s intrigues, they used his example to inspire resistance against the English occupation of Georgia, citing “the unwearied endeavors of Mr. Galphin [to keep] the Indians” on their side. As British officials noted with anxiety, notwithstanding “the Submission of Mr. Galphin … a few days ago 18 of Galphin’s party of Creek Indians returned in a Transport from visiting him … [and] have lately behaved very much Amiss.” However, Galphin could not prolong the inevitable for long, particularly after the surrender of Charleston in May 1780, which for all intents and purposes secured British control over the south. As he awaited trial, all Galphin could do was watch as his wealth – intended to support his family – vanished before his eyes, confiscated under the Disqualifying Act of 1780. Galphin thereby lived out his final days being threatened with execution, cut off from his family and friends, and as witness to a British army seemingly on the verge of crushing the revolution. On December 1, 1780, George Galphin died a prisoner in his own home, never to see the dramatic reversal of American fortunes in 1781.[19]

While indigenous leaders like the Tallassee King and Fat King of Cusseta mourned the passing of their “old friend” and affirmed “Mr. Galphin’s … good Talk … that we the red People and the white should live in Peace,” they also promised to keep Galphin “in continual remembrance.” But the same could not be said of the revolutionary movement and its leaders. For some inexplicable reason, Galphin has been exorcised from the collective memory of the American Revolution, a national forgetting that neglects not only the vital contributions of this man, but also the nature of the Revolutionary War in the south between 1775 and 1778. For most people today, the war from 1775 to 1778 unfolded solely to the north where Washington battled the Howe brothers and Henry Clinton, or Horatio Gates, Daniel Morgan, and Benedict Arnold surrounded and defeated the British at Saratoga. But what is lost in that narrative are the messy realities and dangerous possibilities in the south, in which powerful indigenous nations could have sided with the British and thereby tipped the balance of the war. But because of George Galphin and his labors from 1775 to 1778, that never happened, and the war in the north proceeded as it did because the revolutionaries did not have to contend with British strength in the south.[20]

So what did Galphin’s family receive for his services rendered? Financial collapse, the loss of the family’s patriarch and other kinsmen, and more surprisingly, a blackened reputation that persisted throughout the centuries. As early as 1800, the Georgia and federal legislatures both questioned whether or not Galphin “was a friend to the Revolution.” Then, in 1809, family and friends were forced to testify that “Galphin … during the American war … [was] attached to the Common Cause” and, by “his utmost exertions,” kept the Native peoples of the south “from taking part on either side of the political question.” In conclusion, it was determined that Galphin was “a decided Friend of the American Revolution.” But then again in 1850, members of the House of Representatives declared “Galphin was not known to have been a Whig” and had by some unfathomable “act of … toryism,” betrayed the revolution. And such rumors and half-truths continued. It is about time, then, that the record should – and can – finally be set straight. While George Galphin was somewhat of a reluctant revolutionary, he ultimately proved to be one of the Revolutionary War’s most important figures in the south.[21]

[1] John Stuart to General Gage, November 15, 1775, American Archives: Documents of the American Revolution, 1774-1776, ed. Peter Force, Series 5, Volume 3 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1837), 714-715 (“friendship”); John Stuart to William Knox, March 10, 1777, William Knox Papers, 1757-1811, Box 10: Indian Presents, Reminiscences, & Anecdotes, Folder 3, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor MI (“Rebel Agents”); John Stuart to the Earl of Dartmouth, October 25, 1775, Early American Indian Documents: Treaties and Laws, 1607-1789, Volume XIV: South Carolina and North Carolina Treaties, 1756-1775, ed. Alden T. Vaughan (Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1989-), 380-381 (“Counteract me,” “weight and consequence,” “business”).

[2] Moore and his Florida Loyalists were infamously known among the revolutionaries in Georgia, having fled that colony at the outset of the war, afterwards organizing themselves into guerilla units that raided the Georgia frontier. As early as summer 1776, newspapers and correspondence between revolutionary leaders fixated on the attacks by “Messr. Moore … at the head of a body of plunderers, [who] have been SENT into the Province of Georgia. These freebooters, in the most cruel and wanton manner, destroyed the crops, broke up the plantations, drove off the cattle, and carried away the negroes belonging to several of the Georgia planters,” leaving the province of Georgia “in the greatest distress.” “Extract of a Letter to a Gentleman in London,” August 20, 1776, American Archives, Series 5, 1:1076.

[3] John Stuart to the Lower Creeks, December 4, 1775, Early American Indian Documents: Treaties and Laws, 1607-1789, Volume XII: Georgia and Florida Treaties, 1764-1775, ed. John T. Juricek (Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1989-), 493-494 (“Beloved Man,” Truth,” “Obedience”); Patrick Tonyn to John Perryman, January 24, 1777, Board of Trade and Secretaries of State: America and West Indies, Original Correspondence, Board of Trade: East Florida, 1763-1777, Colonial Office Records, CO 5/557, British National Archives, Kew: Great Britain, 321-322 (“do the Business”); Robert Scott Davis Jr., “George Galphin and the Creek Congress of 1777,” in Wes Taukchiray Papers – Galphin File, MS #198u-200u, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia SC, 8 (“Samuel Moore”); John Rutledge to Unknown, August 30, 1777, John Rutledge Papers, 1739-1800, MS mfm R. 281, Slide 3510, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia SC (“to Kill Galphin”).

[4] Samuel Elbert to General Lachlan McIntosh, August 16, 1777, The Papers of Lachlan McIntosh, 1774-1799, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, GA (“after Mr. Galphin,” “Regiment”); John Rutledge to Unknown, August 30,1777, John Rutledge Papers, 1739-1800 (“way-laid the road,” “Information,” John Gerard, “much alike”); “A Talk from Nea Mico and Neaclucko to George Galphin,” October 13, 1777, George Galphin Letters, 1777-1779, in The Papers of Henry Laurens, Roll 17: Papers Concerning Indian Affairs, South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston SC (Nea Mico and Neaclucko); July 8, 1778, Gazette of the State of South Carolina, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia SC (“Swamp,” “discovered,” “prisoner”); John Stuart to William Knox, August 26, 1777, Board of Trade and Secretaries of State: America and West Indies, Original Correspondence, Secretary of State: Indian Affairs, 1763-1784, Colonial Office Records, CO 5/78, British National Archives, Kew: Great Britain, 220-221 (“Dead”).

[5] It should be noted that the Cherokee were the exception to the rule here, as a portion of the Cherokee nation, known as the Chickamagua “secessionists,” led by the young warrior Dragging Canoe, seized the chaos of the revolution as an opportunity to expel Euro-American settlers from Cherokee territories. The resulting, so-called “Cherokee War of 1776” stood in stark contrast to the neutrality of the Creek, and to a lesser degree, the Chickasaw and Choctaw. For further information, refer to Tyler Boulware, Deconstructing the Cherokee Nation: Town, Region, and Nation among Eighteenth Century Cherokees (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011).

[6] Galphin’s family and friends testified after his death that he “had a considerable and decided control and influence over the Indians … That this influence arose as well from his extensive and honorable trade amongst them, his connexion with one of their women of Indian family distinction, and by whom he had children, as for his kindness and hospitality toward the Indians, always receiving them with good humor and furnishing them amply with such necessaries, as they stood in need of at his hospitable dwelling at Silver Bluff as at his trading houses in the Indian nation.” “Bonds, Bills of Sale & Deeds of Gift,” October 27, 1809, Le Conte Genealogical Collection, 1900-1943, MS #71, Book D, Box 6, Folder 9: Galphin, Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia, Athens GA, 270-272.

[7] February 14, 1774, South Carolina Gazette, 1732-1775, MS CscG, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia SC (“Native of Ireland,” “esteemed”); Thomas P. Slaughter, ed. William Bartram: Travels & Other Writings (New York: The Library of America, 1996), 259-261 (“connexions”); James Habersham to George Galphin, October 8, 1771, Habersham Family Papers, 1712-1842, MS #1787, Folder 4, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, GA (“more in your power”).

[8] South Carolina Council of Safety to George Galphin, October 22, 1775, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume X: December 12, 1774 – January 6, 1776, ed. Philip M. Hamer and David R. Chesnutt (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1988), 491-492 (“great moment”); Tallassee King to the Governor & Council of Georgia, September 22, 1784, Creek Indian Letters, Talks & Treaties, 1705-1837, W.P.A. Georgia Writers’ Project, MS #1500, Box 60, Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia, Athens GA, 161-163 (“as an Indian”); “Letter from Timothy Barnard to the Cussetas,” 2 June 1784, Creek Indian Letters, Talks & Treaties, 1705-1837, 140-142 (“Beloved Man”); Tallassee King’s Son to the Governor & Council of Georgia, n.d. 1783, Creek Indian Letters, Talks & Treaties, 1705-1837, 117-120 (“Mouth of Charleston”); James Graham to John Graham, n.d. 1776, Board of Trade and Secretaries of State: America and West Indies, Original Correspondence, Secretary of State: Miscellaneous, 1771-1778, Colonial Office Records, CO 5/154-157, British National Archives, Kew: Great Britain, 367 (“duped by him”); John Stuart to the Earl of Hillsborough, June 12, 1772, Documents of the American Revolution, Volume V: Transcripts, 1772, ed. K.G. Davies (Shannon, Ireland: Irish University Press, 1972-), 114-117 (“abortive”).

[9] Galphin and Metawney had three Creek children – George Jr., John, and Judith – while Galphin’s relationship with his French mistress, Rachel Dupree, produced two children, Thomas and Martha. In addition, Galphin was a large slave-owner and violently exploited the sex of his female slaves, including Nitehuckey by whom he had a daughter Rose, another slave named Rose by whom he fathered a daughter Barbara, along with the slave Sappho by whom he had two daughters, Rachael and Betsy. Even though born into slavery, Galphin’s African children were taken from their mothers, put into the Galphin household, and freed by Galphin his last will and testament (1776). As for Galphin’s extended family, he surrounded himself with his sisters from Ireland, Martha Crossley and Margaret Holmes, who brought their entire families to Galphin’s Silver Bluff planation in the 1760s. The Crossley and Holmes families included Martha’s husband-in-law William and their five children, and Margaret’s husband-in-law William and their several children, including David Holmes who went on to become Galphin’s right-hand man in the deerskin trade. Finally, Galphin invited and provided for his various nieces, nephews, uncles, aunts, and cousins of the Pooler, Pettycrew, Young, Trotter, Rankin, Robson, Lennard, McMurphy, Dunbar, Barnard, and Foster families (all a mix of Anglo, Irish, and Scottish descent). Last Will and Testament of George Galphin, April 4, 1776, 000051 .L51008, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC.

[10] George Galphin to Timothy Barnard, August 18, 1776, CO 5/77, British National Archives, 559-563 (“power,” “Independence,” “Hell,” “God”); George Galphin to Henry Laurens, February 7, 1776, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XI: January 6, 1776 – November 1, 1771, ed. Philip M. Hamer and David R. Chesnutt (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1988), 93-97 (“Duty”).

[11] Henry Laurens to George Galphin, October 4, 1775, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume X, 447-449 (“Indian Commissioner”); John Stuart to Patrick Tonyn, July 28,1777, CO 5/557, British National Archives, 687-689 (“Emissaries,” “Tools”); John Pigg to George Galphin, 13 June 1778, George Galphin Letters, 1777-1779 (“Informer”).

[12] “Opinion of the Georgia Council of Safety,” August 19, 1776, American Archives, Series 5, Volume 1, 1052 (“irruption”); Charles Lee to the President of South Carolina, August 1, 1776, Charles Lee Letterbook, July 2 – August 27, 1776, MS P3584, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia SC, 50 (“minds”); Thomas Brown to John Stuart, September 29, 1776, CO 5/78, Reel 7, 544-549 (“trading boats,” leaked information); Juan Joseph Eligio de la Puente to Diego Joseph Navarro, April 1, 1778, Transcriptions of Records from Portada del Archivo General de Indias, Texas Tech University in Seville, Spain, Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Collection, MS #1236, Newberry Library, Chicago, IL (“Maestre Galfen”); Benjamin Lincoln to Brigadier General Moultrie, April 22, 1779, Benjamin Lincoln Papers, 1635-1974 [microfilm], Reel 3, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington TX, 281-282 (“Artillery”); Benjamin Lincoln to George Galphin, July 9, 1779, Benjamin Lincoln Papers, 1635-1974, Reel 3, 385 (“hospital”); “Return of the Georgia Brigade of Continental Troops Commanded by Colonel John White,” June 25, 1779, Benjamin Lincoln Papers, 1635-1974, Reel 4, 17 (garrison); Major General Robert Howe to General Gorge Washington, November 3, 1777, in The Papers of George Washington: The Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 3, ed. Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1985), 103-104 (“exertions”).

[13] George Galphin to the Creek Indians, Fall 1776, CO 5/78, Reel 7, 551 (“King’s People,” “many Ships,” “goods,” “Family Affair,” “My Friend”); “Talks from the Commissioners of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department at Salisbury,” November 13, 1775, Henry Laurens Papers, Kendall Collection, in William Gilmore Simms Papers, MS P, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia SC (“Father”); “Journal of a Conference between the American Commissioners and the Creeks at Augusta,” May 16-19, 1776, Early American Indian Documents, Volume XII, 183-190 (“Elder Brother”).

[14] For the particulars of the “British Expulsions of 1777,” see Bryan Rindfleisch, “‘Our Lands are Our Life and Breath’: Coweta, Cusseta, and the Struggle for Creek Territory and Sovereignty during the American Revolution,” Ethnohistory Volume 60, No. 4 (Fall 2013), 581-603.

[15] George Galphin to Henry Laurens, June 25, 1778, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XIII: March 15 – July 6, 1778, ed. Philip M. Hamer, David R. Chesnutt, and C. James Taylor (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992), 513-515 (“Dogs,” “Reward”); “A Talk from the Head Men of the Upper and Lower Creeks – Nea Micko and Neaclucko to George Galphin,” October 13,1777, George Galphin Letters, 1777-1779 (“Night,” “Cussitaw Women”); William McIntosh to Alexander Cameron, 6 July 1777, CO 5/78, Reel 7 (“Long Crop”); George Galphin to Henry Laurens, October 13,1777, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XI, 552-553 (“plundered”).

[16] George Galphin to Henry Laurens, December 29, 1778, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XV: December 9, 1778 – September 1, 1782, ed. Philip M. Hamer, David R. Chesnutt, and C. James Taylor (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1999), 19-21 (“thunder,” “kings troops”); George Galphin to Henry Laurens, March 28, 1779, George Galphin Letters, 1777-1779 (“all night,” “Returned back”); George Galphin to Henry Laurens, December 29, 1778, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XV, 19-21 (“Long”).

[17] Henry Laurens to George Galphin, October 4, 1775, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume X, 447-449 (“Character,” “Tennent,” “Damn”); James Durouzreaux to Galphin Holmes & Co., December 15, 1775, Henry Laurens Papers, Kendall Collection (“West Florida”); John Stuart to George Germain, 10 August 1778, CO 5/79, Reel 8, 27-29 (“exercising”); April 6,1776, Last Will and Testament of George Galphin (disinheritance).

[18] George Galphin to Henry Laurens, October 26, 1778, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XIII, 452-454 (“America & England”); George Galphin to William Jones, October 26, 1776, American Archives, Series 5, Volume 3, 648-650 (“three or four”); George Galphin to Willie Jones October 26, 1776, American Archives, Series 5, Volume 3, 648-650 (“wherever”); George Galphin to Henry Laurens, December 22, 1777, The Papers of Henry Laurens, Volume XII: November 1, 1777 – March 15, 1778, ed. Philip M. Hamer, David R. Chesnutt, and C. James Taylor (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1990), 175-177 (“Devil”).

[19] January 30, 1779, Journal of an Expedition against the Rebels of Georgia in North America under the Orders of Archibald Campbell, Esquire, Lieut. Colol. of His Majesty’s 71st Regimt. (Darien, GA: Ashantilly Press, 1981), 52-53 (Campbell, Galphin’s capture); “Memorial of Lachlan McGillivray on behalf of George Galphin,” June 8, 1780, Colonial Records of the State of Georgia, Volume XV: Journal of the Commons House of Assembly: October 30, 1769 – June 16, 1782, ed. Allen D. Candler (Atlanta: Franklin Publishing Co., 1907), 590-591 (“high treason”); George Galphin to Henry Laurens, March 18, 1779, George Galphin Letters, 1777-1779 (“drive the enemy”); “A Talk delivered by George Galphin … to the Tallassee King and a Number of Warriours and Beloved Men,” November 7, 1779, George Galphin Letters, 1778-1780, Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Collection, Vault Box Ayer MS 313, Newberry Library, Chicago IL (“French and Spanish”); “A Talk delivered at Silver Bluff to George Galphin by the Tallassee King,” November 3,1779, George Galphin Letters, 1778-1780 (“white wing”); December 25, 1779, Virginia Gazette, 1732-1780, Issue 46, page 2, MS 900200 .P900049, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC (“unwearied endeavors”); Alexander Cameron to the Commissioners of Indian Affairs, August 1780, CO 5/81, Reel 8, 592 (“Submission,” “Amiss”); “British Disqualifying Act of 1780,” July 1, 1780, The Revolutionary Records of Georgia, Volume I: 1769-1782, ed. Allen D. Candler (Atlanta: The Franklin-Turner Co., 1908), 348-349.

[20] “Talk delivered by the Tallassee King to the Governor & Council,” September 20, 1784, Georgia Creek Indian Letters, Talks & Treaties, 1705-1837, 159-160 (“old friend,” “remembrance”); “Talk from the Fat King of the Cussitaws,” December 27, 1782, Telamon Cuyler Historical Manuscripts, 1754-1905, MS #1170, Series 1, Folder 25, Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia, Athens GA (“good Talk”).

[21] “Bonds, Bills of Sale & Deeds of Gift,” November 13, 1800, Le Conte Genealogical Collection, 1900-1943, Box 6, Folder 9: Galphin, 224-229 (“friend to the revolution”); “Bonds, Bills of Sale & Deeds of Gift,” October 27, 1809, Le Conte Genealogical Collection, 1900-1943, Box 6, Folder 9: Galphin, 270-272 (“Common Cause,” “exertions,” “political question,” “friend”); July 6, 1850, Congressional Globe: Debates and Proceedings of the Thirty-First Congress, First Session, The Library of Congress, Washington D.C., 931 (http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage) (“Whig,” “toryism”).

12 Comments

Excellent article, and I agree completely on Galphin’s importance. I would argue, that Galphin’s efforts were part of a broader strategy by the Patriot leadership – the provincial congresses and councils of safety – to isolate the British from the three groups – loyalists, Indians, and slaves/free blacks – whose support they would need to a) hold onto power in 1775-1776 and b) regain authority in the southern provinces later in the war. Importantly, it helped that while the British were trying to recruit the active support of the Indians, the Patriots only sought their neutrality as they knew the dangers to their own base of support that could come with arming the Indians to any significant degree.

The SC Council of Safety had to deal with this balance on more than one occasion, such as when Galphin requested ammunition to use to secure the Indians’ neutrality. The Council of Safety held off for a while, before seeking ways to provide ammunition without arming the entire Indian population (such as providing the head men with a small amount of ammunition to distribute only as needed for hunting). One of the most difficult moments for the Council of Safety in Charleston was when it sent ammunition through the backcountry en route to the Indian commissioners to distribute. First local committees of safety seized the ammunition, refusing to believe the Council of Safety would consider arming the Indians. Later, ammunition for the Indians was captured by Patrick Cunningham and his followers in the name of protecting the backcountry inhabitants from Indian depredations, temporarily costing the Council of Safety some support, and setting off much of the conflict that ensued between Patriots and loyalists during the autumn of 1775.

Anyway, like I said, I enjoyed this. The SC Provincial Congress made a wise choice in June 1775 to pick Galphin as one of its initial commissioners.

As a side note, however, I would suggest that while there are few works that focus primarily on Galphin, he has not been entirely “exorcised from the collective memory of the American Revolution.” Michael Morris’ George Galphin and the Transformation of the Georgia-South Carolina Backcountry is the primary study I know of on Galphin himself. There are a number of books that cover the Indians’ role in the south during the war that go into a good amount of detail on Galphin – Jim Piecuch’s Three Peoples, One King; Russell Snapp’s study of John Stuart; Edward Cashin’s book on Thomas Brown, as well as some of his other books. There are a number of others as well. Galphin is certainly under-studied though. Was your dissertation about Galphin? If not, perhaps your second book project?!?

Thanks for the context Dan! As for “exorcising” Galphin from the national memory, you are absolutely correct — Michael Morris just released his book about Galphin (and Michael is a fantastic human being!). Have not had a chance to read it yet, still waiting to get a copy. Same goes for Piecuch, Cashin, Snapp, and others — all good books. However, in a broader sense, unless a person is specifically interested in the American south, they would have absolutely no idea who Galphin was.

As for my work, I focus more on the “Galphin network” in Ireland, the American south, the Indigenous southeast, the British Empire, and the transatlantic world. So, unlike Michael, my interests lay in different worlds and peoples touched by Galphin; he’s more of a window into early America than an actual individual for me.

But I had a ton of fun writing about Galphin in the Revolution! Even though the Revolution only figures into the tail-end of my project, here I was able to talk about things that I don’t, and include sources and material that I’ve removed from the project. As for plans for the future, I’m in the process of revising the dissertation into a book, it’s a bit daunting, but it will happen.

Thanks again for the comments Dan, truly helpful. Best wishes.

Dan, if you’re interested, here’s a more succinct explanation of my project. http://earlyamericanists.com/2015/09/04/george_galphin/

Great article and tie-in to the discovery of THE INDIAN HEAD and the politics of that period. Thanks for sharing this.

There was NO Indian Head in reference to Jeffcoat’s claim in Lexington County. The Indian Head was in Aiken County near Perry, SC. A SC historical approved marker has been installed Sept. 2016 whild the SC Archives rejected Mike Jeffcoat’s application citing n o evidence.

Bryan, I can only say that I am delighted with your work here on Mr. Galphin. I readily admit to having never really focused on him or taken time to consider who he was and is relative importance to the southern campaigns. Many thanks for the learning opportunity.

In prior readings, I remember seeing some argument regarding whether the British tried to bring the southern Indians into the conflict. Specifically, John Stuart has been presented as a man consistently against using the Indians, preferring they remain neutral. Particularly near the beginning of the war and in 1776. Wondering what your thoughts are on Stuart in that regard?

The article here presents a conclusion that ‘one could legitimately argue that Galphin was the one man who stood in the way of” losing the southern states. I’m going to go ahead and confess to having some doubts about this statement. I just don’t see the Creek Indians as powerful enough or willing to act as an army in the field for any length of time. Indians were notorious for making a raid, getting some plunder and blood, then going home. Very similar to the problems with using militia forces. Anyway, I am wondering if you, or Dan, might elaborate a bit on just how the southern states are lost by Galphin’s efforts being less effective? Also, I love the Galphin story and especially enjoy an approach of seeking history through the individual participants, but how effective do you really think Galphin was in his efforts? It seems to me that Creek Indians were fairly active on the Georgia frontier during the years of McGirth and Brown raiding along the Altamaha.

Thank you so kindly for your response Wayne!

As for Stuart, ABSOLUTELY! In 1775 and early 1776, Stuart resisted enlisting the services of indigenous peoples against the revolutionaries, up until the point the revolutionaries forced the situation. The SC Council of Safety (among others) circulated rumors that Stuart intended to incite the Native southeast against the revolutionaries, which in turn fueled the revolutionary movement in the south. By late 1776, Stuart changed his tune, largely on the orders of his superiors in America and London. So, yes, Stuart was initially against involving indigenous peoples in the war. With that said, though, Stuart despised Galphin with a passion (and I mean a passion!). Stuart often wrote to his contacts and friends in Great Britain about how much he hated Galphin, particularly since Galphin repeatedly and frequently co-opted Stuart’s authority as the Superintendent for Indian Affairs in the south between 1770-1776 (as you can imagine, this enraged Stuart to no end). I believe this is another reason that Stuart changed his mind about deploying indigenous allies against the revolutionaries, because he knew Galphin had just as much clout in the Native southeast as he did, and Stuart feared that Galphin might beat him to the punch.

As for your other question, I totally concede your point about the Muskogee (Creek) involvement in military activities during the war! However, I urge you (and others) to keep in mind that there were indigenous interests at play here (this is something that historians of the Revolutionary War often neglect). The Creek Confederacy was more than capable enough of wiping out Georgia settlements in a concerted and sustained manner, as they did in 1773-1774 in response to the Treaty of Augusta (1773) — which itself was engineered by only ONE Creek town – Coweta (for more on this, see my article from 2013 in the journal, “Ethnohistory”). Imagine if ALL of the Creek towns acted in concert with one another (which the revolutionaries constantly feared during the war), the situation in the south would likely have turned out differently than it did – especially for Georgia, the weakest of the southern colonies.

But, fortunately for the revolutionaries, this is not how the Creek world functioned politically and socially. The nature of the Creek Confederacy was that each of its towns — and those town’s leaders/communities — functioned independently of one another, which is why some of the Creek towns sided against the revolutionaries during the war, as opposed to other towns who remained neutral or elected to stick with Galphin. While, yes, this inhibited a confederated threat against the revolutionaries, the revolutionary leadership — such as Henry Laurens among others — did not actually know or believe that. Instead, they were constantly anxious about the threat the Creeks could pose to the southern colonies, especially if the Creek towns would unite against them. This is why Galphin proved so important for the revolutionary movement, because his attachments and relationships with certain Creek towns kept them from following the example of Creek communities like Coweta, Little Tallassee, and others who joined Stuart and the British war effort.

With that said, of course, I’m partial to Galphin and his role in the Revolution, biased you might say. But again, keep in mind the indigenous interests at play during the Revolutionary War, as well as the fact that the Creek Confederacy itself was quite powerful, far more so than non-Native American historians recognize. But, that’s a story for another time (hopefully in my future work!).

As for Galphin’s effectiveness, in my project I talk about how Galphin was hugely successful from 1775 to the summer of 1777. But, after that, things started to fall apart for Galphin and the revolutionary movement in the south (much of which you likely already know). By 1778 and early 1779, the British reoccupied much of the American south, including Galphin’s Silver Bluff plantation (he was placed under house arrest). However, Galphin’s indigenous allies continued to flock to Silver Bluff where they met clandestinely with Galphin, up until his death in December 1780. In fact, following Galphin’s passing is where you see the peak in Native-Loyalist attacks (yes, Thomas Brown and others) against the revolutionaries in the south. Coincidence, maybe…? Or maybe not.

Thank you so much for your interest and questions Wayne! I love meeting new scholars and fans of the Revolution and talking shop! Plus, you have given me excellent questions to consider and work with in the future!

Bryan,

I have been interested for some time now in Alexander Cameron and the role of Indian agents in stirring up the Cherokee War. I am aware of Stuart’s position and the argument back and forth concerning his role (doubtful). However, I personally feel the opposite is true of Alexander Cameron. I think he played a very active role and I suspect he likely did so with approval from superiors. Wondering what information you might have on that subject?

Also wondering if you might elaborate a bit on ‘indigenous interests’. What do you mean by that term? how might they be at play? I am not really knowledgeable about the power of the Creek Confederacy. The frontier assaults of 1774 seem like the nothing more than the killing a couple of families. Nasty stuff but no real threat to the State of Georgia. Granted that talk of it dominated their politics for the rest of the year but, the attacks themselves? Really all that significant? The Ceded Lands populated quickly, this was no lonely Boonesboro in the wilderness without neighbors. More like the later land rushes.

I always end up with a bit of bias towards my subjects too. 🙂

Hi Wayne,

Unfortunately in regards to Alexander Cameron, I don’t know much other than the fact that Galphin and his Creek allies expelled him from Creek Country in 1777 (naturally, he returned shortly after). Apologies. If you think there might be information on Cameron that I would benefit from knowing or learning about, by all means send it my way, please!

As for “indigenous interests,” I tend to privilege the Creek side of things when looking at the Revolution, that’s my bias. If you’re interested, my article in Ethnohistory (Fall 2013) is about the competing strategies of the Creek towns Coweta and Cusseta when confronted with the Revolution, and it lays out a far more succinct argument than what I can do justice to here.

It has been a pleasure Wayne, I truly hope that our paths cross in person and we can continue to talk shop! You have my email, or if not, you can easily find me on the History faculty page at Marquette. Best wishes!

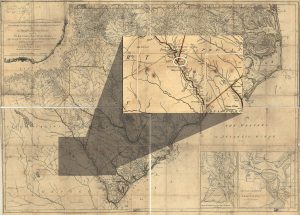

Bryan–I manage the Silver Bluff property, now owned by the National Audubon Society, where George Galphin established his 18th-century home, trading post, and fort.

I am designing a 2′ x 3′ interpretive panel to be placed at the site of the Galphin archaeology dig, so that visitors using our trail system can learn more about the history of Silver Bluff.

I am hoping to have your permission to reproduce the map in your essay that was edited from one in the Library of Congress to feature Silver Bluff. A higher resolution image would be much appreciated.

I look forward to your reply.–Paul Koehler, Director, Silver Bluff Audubon Center & Sanctuary

Of course Paul, please! I would love the opportunity, at some point, to make my way there :-). Take care in these times!

Bryan

Thank you Bryan. I do hope you can visit the site of Galphin’s trading post one day.–Paul